Phd Submission Submitted to Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

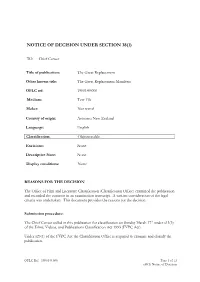

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

Populism, Political Culture, and Marine Le Pen in the 2017 French Presidential Election*

Eleven The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology VOLUME 9 2018 CREATED BY UNDERGRADUATES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Editors-in-Chief Laurel Bard and Julia Matthews Managing Editor Michael Olivieri Senior Editors Raquel Zitani-Rios, Annabel Fay, Chris Chung, Sierra Timmons, and Dakota Brewer Director of Public Relations Juliana Zhao Public Relations Team Katherine Park, Jasmine Monfared, Brittany Kulusich, Erika Lopez-Carrillo, Joy Chen Undergraduate Advisors Cristina Rojas and Seng Saelee Faculty Advisor Michael Burawoy Cover Artist Kate Park Eleven: The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology is the annual publication of Eleven: The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology, a non-profit unincorporated association at the University of California, Berkeley. Grants and Financial Support: This journal was made possible by generous financial support from the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Special Appreciation: We would also like to thank Rebecca Chavez, Holly Le, Belinda White, Tamar Young, and the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Contributors: Contributions may be in the form of articles and review essays. Please see the Guide for Future Contributors at the end of this issue. Review Process: Our review process is double-blind. Each submission is anonymized with a number and all reviewers are likewise assigned a specific review number per submission. If an editor is familiar with any submission, she or he declines to review that piece. Our review process ensures the highest integrity and fairness in evaluating submissions. Each submission is read by three trained reviewers. Subscriptions: Our limited print version of the journal is available without fee. If you would like to make a donation for the production of future issues, please inquire at [email protected]. -

Submission to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Submission to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Review of GERMANY 64th session, 24 September - 12 October 2018 INTERNATIONALE FRAUENLIGA FÜR WOMEN’S INTERNATIONAL LEAGUE FOR FRIEDEN UND FREIHEIT PEACE & FREEDOM DEUTSCHLAND © 2018 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction, copying, distribution, and transmission of this publication or parts thereof so long as full credit is given to the publishing organisation; the text is not altered, transformed, or built upon; and for any reuse or distribution, these terms are made clear to others. 1ST EDITION AUGUST 2018 Design and layout: WILPF www.wilpf.org // www.ecchr.eu Contents I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Germany’s extraterritorial obligations in relation to austerity measures implemented in other countries ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................................... 4 III. Increased domestic securitisation ............................................................................................ 5 a) Steep increase in demands for ‘small’ licences for weapons ............................................................... 5 b) Increase in anti-immigrant sentiments .............................................................................................. -

Comparison of Constitutionalism in France and the United States, A

A COMPARISON OF CONSTITUTIONALISM IN FRANCE AND THE UNITED STATES Martin A. Rogoff I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 22 If. AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM ..................... 30 A. American constitutionalism defined and described ......................................... 31 B. The Constitution as a "canonical" text ............ 33 C. The Constitution as "codification" of formative American ideals .................................. 34 D. The Constitution and national solidarity .......... 36 E. The Constitution as a voluntary social compact ... 40 F. The Constitution as an operative document ....... 42 G. The federal judiciary:guardians of the Constitution ...................................... 43 H. The legal profession and the Constitution ......... 44 I. Legal education in the United States .............. 45 III. THE CONsTrrTION IN FRANCE ...................... 46 A. French constitutional thought ..................... 46 B. The Constitution as a "contested" document ...... 60 C. The Constitution and fundamental values ......... 64 D. The Constitution and nationalsolidarity .......... 68 E. The Constitution in practice ...................... 72 1. The Conseil constitutionnel ................... 73 2. The Conseil d'ttat ........................... 75 3. The Cour de Cassation ....................... 77 F. The French judiciary ............................. 78 G. The French bar................................... 81 H. Legal education in France ........................ 81 IV. CONCLUSION ........................................ -

World Jewish Congress on Eliminating Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion Or Belief and the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG 16)

Submission by the World Jewish Congress on Eliminating Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief and the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG 16) Introduction The World Jewish Congress is the representative body of more than 100 Jewish communities around the globe. Since its founding in 1936, the WJC has prioritized the values embodied in SDG 16 for the achievement of peaceful, just and inclusive societies. It does so by, inter alia, countering antisemitism and hatred, advocating for the rights of minorities and spearheading interfaith understanding. Antisemitism is a grave threat to the attainment of SDG 16, undermining the prospect of peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence. Antisemitism concerns us all because it poses a threat to the most fundamental values of democracy and human rights. As the world’s “oldest hatred,” antisemitism exposes the failings in each society. Jews are often the first group to be scapegoated but, unfortunately, they are not the last. Hateful discourse that starts with the Jews expands to other members of society and threatens the basic fabric of modern democracies, rule of law and the protection of human rights. Antisemitism is on the rise globally. Virtually every opinion poll and study in the last few years paints a very dark picture of the rise in antisemitic sentiments and perceptions. As examples: • According to the French interior ministry, in 2018, antisemitic incidents rose sharply by 74% compared to the year before.1 In 2019, antisemitic acts in the country increased by another 27%.2 • According to crime data from the German government, in 2018 there was a 60% rise in physical attacks against Jewish targets, compared to 2017.3 • In Canada, violent antisemitic incidents increased by 27% in 2019, making the Jewish community the most targeted religious minority in the country.4 1 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/12/world/europe/paris-anti-semitic-attacks.html. -

Michel Houellebecq on Some Ethical Issues Zuzana

Ethics & Bioethics (in Central Europe), 2019, 9 (3–4), 190–196 DOI:10.2478/ebce-2019-0013 A bitter diagnostic of the ultra-liberal human: Michel Houellebecq on some ethical issues Zuzana Malinovská1 & Ján Živčák2 Abstract The paper examines the ethical dimensions of Michel Houellebecq’s works of fiction. On the basis of keen diagnostics of contemporary Western culture, this world-renowned French writer predicts the destructive social consequences of ultra-liberalism and enters into an argument with transhumanist theories. His writings, depicting the misery of contemporary man and imagining a new human species enhanced by technologies, show that neither the so-called neo-humans nor the “last man” of liberal democracies can reach happiness. The latter can only be achieved if humanist values, shared by previous generations and promoted by the great 19th-century authors (Balzac, Flaubert), are reinvented. Keywords: contemporary French literature, ultra-liberalism, humanism, transhumanism, end of man Introduction Since the time of Aristotle, the axiom of ontological inseparability and mutual compatibility of aesthetics and ethics within a literary work has been widely accepted by literary theorists. Even the (apparent) absence of ethics espoused by some adherents of extreme formalist experiments around the middle and in the second half of the 20th century (e.g. the ‘Tel Quel’ group) presupposes an ethical positioning. In France, forms of literary expression which accord high priority to ethical/moral questioning have a significant tradition. The so-called “ethical generation”, writing mainly in the 1930s (Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Georges Bernanos, André Malraux, etc.), is clear evidence of this. At present, the French author whose ethical as well as aesthetic positions generate probably the most controversy is Michel Houellebecq (Clément & Wesemael, 2007). -

“FRANCE DESERVES to BE FREE”: CONSTITUTING FRENCHNESS in MARINE LE PEN's NATIONAL FRONT/NATIONAL RALLY Submitted By

THESIS “FRANCE DESERVES TO BE FREE”: CONSTITUTING FRENCHNESS IN MARINE LE PEN’S NATIONAL FRONT/NATIONAL RALLY Submitted by Lauren Seitz Department of Communication Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 2020 Master’s Committee: Advisor: Karrin Anderson Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager Courtenay Daum Copyright by Lauren Nicole Seitz 2020 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “FRANCE DESERVES TO BE FREE”: CONSTITUTING FRENCHNESS IN MARINE LE PEN’S NATIONAL FRONT/NATIONAL RALLY This thesis employs constitutive rhetoric to analyze French far-right politician Marine Le Pen’s discourse. Focusing on ten of Le Pen’s speeches given between 2015 and 2019, I argue that Le Pen made use of Kenneth Burke’s steps of scapegoating and purification as a way to rewrite French national identity and constitute herself as a revolutionary political leader. Le Pen first identified with the subjects and system that she scapegoats. Next, she cast out elites, globalists, and immigrants, identifying them as scapegoats of France’s contemporary identity split. Finally, by disidentifying with the scapegoats, Le Pen constituted her followers as always already French patriots and herself as her leader. This allowed her to propose a new form of French national identity that was undergirded by far-right ideals and discourse of revolution. This thesis presents several implications for understanding contemporary French national identity, the far right, and women politicians. It also contributes to the project of internationalizing public address research in Communication Studies. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, thank you to my advisor, Kari Anderson. I truly could not have completed this thesis without your guidance, encouragement, and advice. -

Writing Emotions

Ingeborg Jandl, Susanne Knaller, Sabine Schönfellner, Gudrun Tockner (eds.) Writing Emotions Lettre 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 Ingeborg Jandl, Susanne Knaller, Sabine Schönfellner, Gudrun Tockner (eds.) Writing Emotions Theoretical Concepts and Selected Case Studies in Literature 2017-05-15 15-01-57 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 0247461218271772|(S. 1- 4) TIT3793_KU.p 461218271780 Printed with the support of the State of Styria (Department for Health, Care and Science/Department Science and Research), the University of Graz, and the Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Graz. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3793-3. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative -

Submission by the Human Rights Council of Australia Inc. to The

Submission by the Human Rights Council of Australia Inc. to the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs References Committee Inquiry into Nationhood, National Identity and Democracy Abstract This submission argues that it is critical for community cohesion and in respect of observance of international human rights to recognise and address the racist elements present in the movements described as “populist, conservative nationalist and nativist” which the inquiry addresses. These elements include the promotion of concepts of "white nationalism" which are largely imported from North America and Europe. Racist movements adopt sophisticated recruitment and radicalisation techniques similar to those seen among jihadists. Hate speech requires a strengthened national response and we recommend that its most extreme forms be criminalised in federal law, taking into account relevant human rights principles. A comprehensive annual report is required to ensure that key decision makers including parliamentarians are well-informed about the characteristics and methods of extremist actors. Further, noting the openly racist call for a return of the “White Australia” policy by a former parliamentarian, a Parliamentary Code of Ethics, which previous inquiries have recommended, is now essential. The immigration discourse is particularly burdened with implicit (and sometimes explicit) racist messaging. It is essential that an evidence base be developed to remove racist effects from immigration and other national debates. International human rights are a purpose-designed response to racism and racist nationalism. They embody the learned experience of the postwar generation. Human rights need to be drawn on more systematically to promote community cohesion and counter hate. Community cohesion and many Australians would be significantly harmed by any return to concepts of an ethnically or racially defined “nation”. -

The French Party System Forms a Benchmark Study of the State of Party Politics in France

evans cover 5/2/03 2:37 PM Page 1 THE FRENCH PARTY SYSTEM THE FRENCHPARTY This book provides a complete overview of political parties in France. The social and ideological profiles of all the major parties are analysed chapter by chapter, highlighting their principal functions and dynamics within the system. This examination is THE complemented by analyses of bloc and system features, including the pluralist left, Europe, and the ideological space in which the parties operate. In particular, the book addresses the impressive FRENCH capacity of French parties and their leaders to adapt themselves to the changing concerns of their electorates and to a shifting PARTY institutional context. Contrary to the apparently fragmentary system and increasingly hostile clashes between political personalities, the continuities in the French political system seem SYSTEM destined to persist. Drawing on the expertise of its French and British contributors, The French party system forms a benchmark study of the state of party politics in France. It will be an essential text for all students of Edited by French politics and parties, and of interest to students of European Evans Jocelyn Evans politics more generally. ed. Jocelyn Evans is Lecturer in Politics at the University of Salford The French party system The French party system edited by Jocelyn A. J. Evans Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Copyright © Manchester University Press 2003 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. This electronic version has been made freely available under a Creative Commons (CC-BY-NC-ND) licence, which permits non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction provided the author(s) and Manchester University Press are fully cited and no modifications or adaptations are made. -

Houellebecq's Priapism

Houellebecq’s Priapism: The Failure of Sexual Liberation in Michel Houellebecq’s Novels and Essays Benjamin Boysen University of Southern Denmark The truth is scandalous. But nothing is worth anything without it. 477 (Rester vivant 27) Jed had never had such an erection; it was truly painful. (The Map and the Territory 51; translation modified) In the following, I will argue that Michel Houellebecq’s essays and novels give voice to what I would label priapism. Houellebecq’s dire analysis of postmodern societies and the malaise of the Western instinctual structure, and his vehement critique of the sexual liberation of the sixties as well as of Western individualism and liberalism are well known and well documented.1 However, here I want to draw special atten- tion to the way his texts embody an unusually bizarre and latently self-contradictory position of priapism. Priapism is a notion extremely well suited to the ways in which Houellebecq’s novels and essays portray an involuntary desire or libido that is ordered from outside the subject, and thus is unfree. Priapism is a medical diagnosis for chronic erection not caused by physical, psychological, or erotic stimuli. It is poten- tially a harmful state, often quite painful. Untreated, the prognosis is impotence. For an outside party, the condition seems to designate lust for life, excitation, and plea- sure, but the patient feels the opposite: pain, humiliation, and despair. Presenting a vision of a post-industrial neoliberal consumer society obsessed with pleasure and desire, dictating how the individual must desire and enjoy, Houellebecq’s art dis- closes how Western societies’ instinctual structure entails an alienated, stressed, and frustrated libido.