IAPN Submission 2020 Hearing on Italian MOU Renewal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Classification Decision for the Great

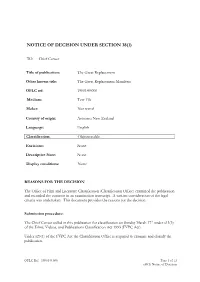

NOTICE OF DECISION UNDER SECTION 38(1) TO: Chief Censor Title of publication: The Great Replacement Other known title: The Great Replacement Manifesto OFLC ref: 1900149.000 Medium: Text File Maker: Not stated Country of origin: Aotearoa New Zealand Language: English Classification: Objectionable. Excisions: None Descriptive Note: None Display conditions: None REASONS FOR THE DECISION The Office of Film and Literature Classification (Classification Office) examined the publication and recorded the contents in an examination transcript. A written consideration of the legal criteria was undertaken. This document provides the reasons for the decision. Submission procedure: The Chief Censor called in this publication for classification on Sunday March 17th under s13(3) of the Films, Videos, and Publications Classification Act 1993 (FVPC Act). Under s23(1) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office is required to examine and classify the publication. OFLC Ref: 1900149.000 Page 1 of 13 s38(1) Notice of Decision Under s23(2) of the FVPC Act the Classification Office must determine whether the publication is to be classified as unrestricted, objectionable, or objectionable except in particular circumstances. Section 23(3) permits the Classification Office to restrict a publication that would otherwise be classified as objectionable so that it can be made available to particular persons or classes of persons for educational, professional, scientific, literary, artistic, or technical purposes. Synopsis of written submission(s): No submissions were required or sought in relation to the classification of the text. Submissions are not required in cases where the Chief Censor has exercised his authority to call in a publication for examination under section 13(3) of the FVPC Act. -

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism

Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Robert Fredona Working Paper 18-021 Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert Harvard Business School Robert Fredona Harvard Business School Working Paper 18-021 Copyright © 2017 by Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Merchants and the Origins of Capitalism Sophus A. Reinert and Robert Fredona ABSTRACT: N.S.B. Gras, the father of Business History in the United States, argued that the era of mercantile capitalism was defined by the figure of the “sedentary merchant,” who managed his business from home, using correspondence and intermediaries, in contrast to the earlier “traveling merchant,” who accompanied his own goods to trade fairs. Taking this concept as its point of departure, this essay focuses on the predominantly Italian merchants who controlled the long‐distance East‐West trade of the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Until the opening of the Atlantic trade, the Mediterranean was Europe’s most important commercial zone and its trade enriched European civilization and its merchants developed the most important premodern mercantile innovations, from maritime insurance contracts and partnership agreements to the bill of exchange and double‐entry bookkeeping. Emerging from literate and numerate cultures, these merchants left behind an abundance of records that allows us to understand how their companies, especially the largest of them, were organized and managed. -

Debt Policy Under Constraints: Philip II, the Cortes, and Genoese Bankers1 by CARLOS ÁLVAREZ-NOGAL and CHRISTOPHE CHAMLEY*

bs_bs_banner Economic History Review (2013) Debt policy under constraints: Philip II, the Cortes, and Genoese bankers1 By CARLOS ÁLVAREZ-NOGAL and CHRISTOPHE CHAMLEY* Under Philip II, Castile was the first country with a large nation-wide domestic public debt. A new view of that fiscal system is presented that is potentially relevant for other fiscal systems in Europe before 1800. The credibility of the debt, mostly in perpetual redeemable annuities, was enhanced by decentralized funding through taxes administered by cities making up the Realm in the Cortes.The accumulation of short-term debt depended on refinancing through long-term debt. Financial crises in the short-term debt occurred when the service of the long-term debt reached the revenues of its servicing taxes. They were not caused by liquidity crises and were resolved after protracted negotiations in the Cortes by tax increases and interest rate reductions. ing Philip II, as head of the first modern super-power, managed a budget on Ka scale that had not been seen since the height of the Roman Empire.2 No state before had faced such extraordinary fluctuations and imbalances, both in revenue and expenditure. Large military expenses were required by the politics of Europe and the revolution in military technology. The variability in both revenue and expenses, coupled with a large foreign component, was met by large public borrowings up to modern levels, a historical innovation that, in later centuries, would be followed by the Netherlands, France, and England. Like eighteenth- century England, Castile (about 80 per cent of modern-day Spain) established its military supremacy through its superior ability to mobilize large resources through borrowing. -

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: a Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov a Thesis

The Exclusion of Conservative Women from Feminism: A Case Study on Marine Le Pen of the National Rally1 Nicole Kiprilov A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science for honors Duke University Durham, North Carolina 2019 1 Note name change from National Front to National Rally in June 2018 1 Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to a number of people who were integral to my research and thesis-writing journey. I thank my advisor, Dr. Michael Munger, for his expertise and guidance. I am also very grateful to my two independent study advisors, Dr. Beth Holmgren from the Slavic and Eurasian Studies department and Dr. Michèle Longino from the Romance Studies department, for their continued support and guidance, especially in the first steps of my thesis-writing. In addition, I am grateful to Dr. Heidi Madden for helping me navigate the research process and for spending a great deal of time talking through my thesis with me every step of the way, and to Dr. Richard Salsman, Dr. Genevieve Rousseliere, Dr. Anne Garréta, and Kristen Renberg for all of their advice and suggestions. None of the above, however, are responsible for the interpretations offered here, or any errors that remain. Thank you to the entire Duke Political Science department, including Suzanne Pierce and Liam Hysjulien, as well as the Duke Roman Studies department, including Kim Travlos, for their support and for providing me this opportunity in the first place. Finally, I am especially grateful to my Mom and Dad for inspiring me. Table of Contents 2 Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………………4 Part 1 …………………………………………………………………………………………...5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………..5 Purpose ………………………………………………………………………………..13 Methodology and Terms ……………………………………………………………..16 Part 2 …………………………………………………………………………………………..18 The National Rally and Women ……………………………………………………..18 Marine Le Pen ………………………………………………………………………...26 Background ……………………………………………………………………26 Rise to Power and Takeover of National Rally ………………………….. -

Populism, Political Culture, and Marine Le Pen in the 2017 French Presidential Election*

Eleven The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology VOLUME 9 2018 CREATED BY UNDERGRADUATES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Editors-in-Chief Laurel Bard and Julia Matthews Managing Editor Michael Olivieri Senior Editors Raquel Zitani-Rios, Annabel Fay, Chris Chung, Sierra Timmons, and Dakota Brewer Director of Public Relations Juliana Zhao Public Relations Team Katherine Park, Jasmine Monfared, Brittany Kulusich, Erika Lopez-Carrillo, Joy Chen Undergraduate Advisors Cristina Rojas and Seng Saelee Faculty Advisor Michael Burawoy Cover Artist Kate Park Eleven: The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology is the annual publication of Eleven: The Undergraduate Journal of Sociology, a non-profit unincorporated association at the University of California, Berkeley. Grants and Financial Support: This journal was made possible by generous financial support from the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Special Appreciation: We would also like to thank Rebecca Chavez, Holly Le, Belinda White, Tamar Young, and the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. Contributors: Contributions may be in the form of articles and review essays. Please see the Guide for Future Contributors at the end of this issue. Review Process: Our review process is double-blind. Each submission is anonymized with a number and all reviewers are likewise assigned a specific review number per submission. If an editor is familiar with any submission, she or he declines to review that piece. Our review process ensures the highest integrity and fairness in evaluating submissions. Each submission is read by three trained reviewers. Subscriptions: Our limited print version of the journal is available without fee. If you would like to make a donation for the production of future issues, please inquire at [email protected]. -

Submission to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

Submission to the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Review of GERMANY 64th session, 24 September - 12 October 2018 INTERNATIONALE FRAUENLIGA FÜR WOMEN’S INTERNATIONAL LEAGUE FOR FRIEDEN UND FREIHEIT PEACE & FREEDOM DEUTSCHLAND © 2018 Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom Permission is granted for non-commercial reproduction, copying, distribution, and transmission of this publication or parts thereof so long as full credit is given to the publishing organisation; the text is not altered, transformed, or built upon; and for any reuse or distribution, these terms are made clear to others. 1ST EDITION AUGUST 2018 Design and layout: WILPF www.wilpf.org // www.ecchr.eu Contents I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 II. Germany’s extraterritorial obligations in relation to austerity measures implemented in other countries ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommendations ...................................................................................................................................... 4 III. Increased domestic securitisation ............................................................................................ 5 a) Steep increase in demands for ‘small’ licences for weapons ............................................................... 5 b) Increase in anti-immigrant sentiments .............................................................................................. -

The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa's Diary

Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.) The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Edited by Richard Wittmann Memoria. Fontes Minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici Pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.): The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak © Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, Bonn 2017 Redaktion: Orient-Institut Istanbul Reihenherausgeber: Richard Wittmann Typeset & Layout: Ioni Laibarös, Berlin Memoria (Print): ISSN 2364-5989 Memoria (Internet): ISSN 2364-5997 Photos on the title page and in the volume are from Regina Salomea Pilsztynowa’s memoir »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (Echo na świat podane procederu podróży i życia mego awantur), compiled in 1760, © Czartoryski Library, Krakow. Editor’s Preface From the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to Istanbul: A female doctor in the eighteenth-century Ottoman capital Diplomatic relations between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Com- monwealth go back to the first quarter of the fifteenth century. While the mutual con- tacts were characterized by exchange and cooperation interrupted by periods of war, particularly in the seventeenth century, the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) marked a new stage in the history of Ottoman-Polish relations. In the light of the common Russian danger Poland made efforts to gain Ottoman political support to secure its integrity. The leading Polish Orientalist Jan Reychman (1910-1975) in his seminal work The Pol- ish Life in Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century (»Życie polskie w Stambule w XVIII wieku«, 1959) argues that the eighteenth century brought to life a Polish community in the Ottoman capital. -

Comparison of Constitutionalism in France and the United States, A

A COMPARISON OF CONSTITUTIONALISM IN FRANCE AND THE UNITED STATES Martin A. Rogoff I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 22 If. AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM ..................... 30 A. American constitutionalism defined and described ......................................... 31 B. The Constitution as a "canonical" text ............ 33 C. The Constitution as "codification" of formative American ideals .................................. 34 D. The Constitution and national solidarity .......... 36 E. The Constitution as a voluntary social compact ... 40 F. The Constitution as an operative document ....... 42 G. The federal judiciary:guardians of the Constitution ...................................... 43 H. The legal profession and the Constitution ......... 44 I. Legal education in the United States .............. 45 III. THE CONsTrrTION IN FRANCE ...................... 46 A. French constitutional thought ..................... 46 B. The Constitution as a "contested" document ...... 60 C. The Constitution and fundamental values ......... 64 D. The Constitution and nationalsolidarity .......... 68 E. The Constitution in practice ...................... 72 1. The Conseil constitutionnel ................... 73 2. The Conseil d'ttat ........................... 75 3. The Cour de Cassation ....................... 77 F. The French judiciary ............................. 78 G. The French bar................................... 81 H. Legal education in France ........................ 81 IV. CONCLUSION ........................................ -

World Jewish Congress on Eliminating Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion Or Belief and the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG 16)

Submission by the World Jewish Congress on Eliminating Intolerance and Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief and the Achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 16 (SDG 16) Introduction The World Jewish Congress is the representative body of more than 100 Jewish communities around the globe. Since its founding in 1936, the WJC has prioritized the values embodied in SDG 16 for the achievement of peaceful, just and inclusive societies. It does so by, inter alia, countering antisemitism and hatred, advocating for the rights of minorities and spearheading interfaith understanding. Antisemitism is a grave threat to the attainment of SDG 16, undermining the prospect of peaceful, just and inclusive societies which are free from fear and violence. Antisemitism concerns us all because it poses a threat to the most fundamental values of democracy and human rights. As the world’s “oldest hatred,” antisemitism exposes the failings in each society. Jews are often the first group to be scapegoated but, unfortunately, they are not the last. Hateful discourse that starts with the Jews expands to other members of society and threatens the basic fabric of modern democracies, rule of law and the protection of human rights. Antisemitism is on the rise globally. Virtually every opinion poll and study in the last few years paints a very dark picture of the rise in antisemitic sentiments and perceptions. As examples: • According to the French interior ministry, in 2018, antisemitic incidents rose sharply by 74% compared to the year before.1 In 2019, antisemitic acts in the country increased by another 27%.2 • According to crime data from the German government, in 2018 there was a 60% rise in physical attacks against Jewish targets, compared to 2017.3 • In Canada, violent antisemitic incidents increased by 27% in 2019, making the Jewish community the most targeted religious minority in the country.4 1 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/12/world/europe/paris-anti-semitic-attacks.html. -

Northern Europe, 1350-1560

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Volckart, Oliver Working Paper The influence of information costs on the integration of financial markets: Northern Europe, 1350-1560 SFB 649 Discussion Paper, No. 2006,049 Provided in Cooperation with: Collaborative Research Center 649: Economic Risk, Humboldt University Berlin Suggested Citation: Volckart, Oliver (2006) : The influence of information costs on the integration of financial markets: Northern Europe, 1350-1560, SFB 649 Discussion Paper, No. 2006,049, Humboldt University of Berlin, Collaborative Research Center 649 - Economic Risk, Berlin This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/25132 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been -

Venetian Foreign Affairs from 1250 to 1381: the Wars with Genoa and Other External Developments

Venetian Foreign Affairs from 1250 to 1381: The Wars with Genoa and Other External Developments By Mark R. Filip for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in History College of Liberal Arts and Sciences University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 1988 Table of Contents Major Topics page Introduction 1 The First and Second Genoese Wars 2 Renewed Hostilities at Ferrara 16 Tiepolo's Attempt at Revolution 22 A New Era of Commercial Growth 25 Government in Territories of the Republic 35 The Black Death and Third ' < 'ioese War 38 Portolungo 55 A Second Attempt at Rcvoiut.on 58 Doge Gradenigo and Peace with Genoa 64 Problems in Hungary and Crete 67 The Beginning of the Contarini Dogcship 77 Emperor Paleologus and the War of Chioggia 87 The Battle of Pola 94 Venetian Defensive Successes 103 Zeno and the Venetian Victory 105 Conclusion 109 Endnotes 113 Annotated Bibliography 121 1 Introduction In the years preceding the War of Chioggia, Venetian foreign affairs were dominated by conflicts with Genoa. Throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the two powers often clashed in open hostilities. This antagonism between the cities lasted for ten generations, and has been compared to the earlier rivalry between Rome and Carthage. Like the struggle between the two ancient powers, the Venetian/Gcnoan hatred stemmed from their competitive relationship in maritime trade. Unlike land-based rivals, sea powers cannot be separated by any natural boundary or agree to observe any territorial spheres of influence. Trade with the Levant, a source of great wealth and prosperity for each of the cities, required Venice and Genoa to come into repeated conflict in ports such as Chios, Lajazzo, Acre, and Tyre. -

Michel Houellebecq on Some Ethical Issues Zuzana

Ethics & Bioethics (in Central Europe), 2019, 9 (3–4), 190–196 DOI:10.2478/ebce-2019-0013 A bitter diagnostic of the ultra-liberal human: Michel Houellebecq on some ethical issues Zuzana Malinovská1 & Ján Živčák2 Abstract The paper examines the ethical dimensions of Michel Houellebecq’s works of fiction. On the basis of keen diagnostics of contemporary Western culture, this world-renowned French writer predicts the destructive social consequences of ultra-liberalism and enters into an argument with transhumanist theories. His writings, depicting the misery of contemporary man and imagining a new human species enhanced by technologies, show that neither the so-called neo-humans nor the “last man” of liberal democracies can reach happiness. The latter can only be achieved if humanist values, shared by previous generations and promoted by the great 19th-century authors (Balzac, Flaubert), are reinvented. Keywords: contemporary French literature, ultra-liberalism, humanism, transhumanism, end of man Introduction Since the time of Aristotle, the axiom of ontological inseparability and mutual compatibility of aesthetics and ethics within a literary work has been widely accepted by literary theorists. Even the (apparent) absence of ethics espoused by some adherents of extreme formalist experiments around the middle and in the second half of the 20th century (e.g. the ‘Tel Quel’ group) presupposes an ethical positioning. In France, forms of literary expression which accord high priority to ethical/moral questioning have a significant tradition. The so-called “ethical generation”, writing mainly in the 1930s (Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Georges Bernanos, André Malraux, etc.), is clear evidence of this. At present, the French author whose ethical as well as aesthetic positions generate probably the most controversy is Michel Houellebecq (Clément & Wesemael, 2007).