Laudatio for the Laurea Doctor of Laws Honoris Causa of Derek C. Bok from Complutense University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title IX Coordinator and Director, Human Resources and Equal Opportunity Musicians to Engage a Local and Global Community Throug

Title IX Coordinator and Director, Human Resources and Equal Opportunity The Curtis Institute of Music, a private school dedicated to the training and education of exceptionally gifted young musicians, invites nominations and applications for the position of Title IX Coordinator and Director, Human Resources and Equal Opportunity. The Curtis Institute seeks a strategic thinker and a relationship-driven community member who fosters productive collaborations, is trustworthy and approachable, and strives to serve as a valued and reliable resource to students, faculty, staff, and the administration. Serving as a newly added member of the President’s cabinet, the Director will oversee Curtis’s Title IX function and work in partnership with the Senior Associate Dean and Special Advisor to the President for Strategic Engagement, and members of the Ombuds Office to develop institutional equity initiatives across the campus. Reporting to the Senior Vice President of Administration, with a dotted line to the President & CEO, the Director will lead the division of Title IX, human resources, and equal opportunity services, and participate in a newly formed task force designed to support the well-being of students, staff, alumni, and faculty. The position will also have an open and confidential line to the Board of Trustees. This critical hire will be well-positioned to help Curtis remain true to its core mission: to educate and train exceptionally gifted young musicians to engage a local and global community through the highest level of artistry. 1 The Director will bring proficiency in both the current and emerging regulatory environments, as well as a deep understanding of national issues and trends as they relate specifically to Title IX and equal opportunity regulations. -

Curtis Institute of Music

C URTIS INST I TUT E O F MUS IC C ATA LOGU E 1 938- 1 939 R I T T E N H O U S E S Q U A R E P HI L A D E L P HI A P E NN S Y L V A NI A THE C RT S ST T TE OF M S C o ded U I IN I U U I , f un in 1 1 M o i e C i Bok e come 9 4 by ary L u s urt s , w l s f i i i students o all nat onal t es . Th e Curtis Institute receive s its support from Th e M o i e C i Bok Fo d i o i s ary L u s urt s un at n , operated under a Charter of th e Comm onwe alth of Pe i an d i s cc edi e d for th e nnsylvan a , fully a r t i c onferr ng of Degrees . Th e Curtis Institute i s approved by th e United State s Go vernment as an institution of learning for th e i i of n on - o o ei de tra n ng qu ta f r gn stu nts , in m A f 1 1 accordance with th e Im igration ct o 9 4 . T H E C U R T I S I N S T I T U T E O F M U S I C M ARY LOUISE CURTIS BOK ' Prcud mt CURTIS BOK Vice- President CARY W BOK Secretary LL PHILIP S . -

National Historic Landmark Nomination Bok

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BOK TOWER GARDENS Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: MOUNTAIN LAKE SANCTUARY AND SINGING TOWER Other Name/Site Number: BOK TOWER GARDENS 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Burns Ave. and Tower Blvd. Not for publication: (3 miles north of Lake Wales) City/Town: Lake Wales Vicinity: X State: FL County: Polk Code: 105 Zip Code: 33859-3810 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X_ Building(s): Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 8 5 buildings 1 __ sites 6 structures 1 objects 15 12 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 15 (District) Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BOK TOWER GARDENS Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

March 2012 Pp. 2-19.Indd

The Royal School of Church Mu- Other new projects include a four- Michigan: Joseph Brink of Yale Univer- Here & There sic (RSCM) is publishing four short-list- manual organ for the Kennedy Center sity, Stephan Burton of Brigham Young ed anthems from the King James Bible in Washington, D.C.; new three-manual University, Nick Huang of Yale Univer- Composition Competition, which was or- organs at St. John’s Episcopal Church in sity, Joseph Peeples of Brigham Young Bärenreiter announces new releas- ganized by the King James Bible Trust to Cold Spring Harbor, New York, and St. Univeristy, and Chelsea Vaught of the es. The Organ Plus One series presents mark the 400th anniversary of the bible’s John’s Episcopal Church, Georgetown University of Kansas. The next congress pieces—both freely composed and hymn publication in 1611. The RSCM spon- Parish, Washington, D.C.; and a number of the GCNA will be hosted by Clemson tune-based, and both original works as sored one of two categories—submission of projects to restore or rebuild existing University in Clemson, South Carolina, well as arrangements—for organ plus a of an anthem or worship-song suitable pipe organs. For information: June 19–22, 2012. solo instrument. The editions include solo for use in churches and schools. There <www.casavant.ca>. parts in C, B-fl at, E-fl at, and F, thus ac- were over one hundred submissions to Washington National Cathedral commodating many diverse instruments; this category alone. C. B. Fisk, Inc. is celebrating its 50th Washington National Cathedral was the range of the instrumental parts is in The winning anthem, The Mystery anniversary. -

Commager, Carr, Chafee, Gellhorn, Bok, Baxter: Civil Liberties Under

THE YALE LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 61 of securities is entitled to have. As previously indicated, the second specific suggestion has been incorporated in the definition of "public offering" at least since 1935. Undoubtedly, direct placement needs more research and more first-hand investigation. Professor Corey has been a pioneer, setting up targets for cri- ticism, and establishing landmarks for others to embellish. MYER FELDMANt CIVIL LIBERTIES UNDER ATTACK. By Henry Steele Commager, Robert K. Carr, Zechariah Chafee Jr., Walter Gellhorn, Curtis Bok, and James P. Baxter III. Edited by Clair Wilcox. William J. Cooper Foundation Lectures, Swarthmore College. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1951. Pp. 155. $3.50. PROFESSOR Paul Freund of the Harvard Law School once remarked that the charge against the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee (placed on the Attorney General's list of subversive organizations) seemed to be that they were "prematurely anti-fascist." In the same vein, many books in recent years which have protested against infringements upon civil liberties have seemed to lack popular response because they were "premature" protests--protests against restrictions which had not percolated down far enough into the national system to cause widespread concern. With the publication of Alan Barth's The Loyalty of Free Men, Walter Gellhorn's Security, Loyalty and Science, and now, six lectures gathered in Civil Liberties Under Attack, the time seems to have become "mature" for re-examining our civil freedoms, 1951 edition. The issuance of this book is reminiscent of May, 1920, in the period of the notorious Palmer Raids and the anti-radical terror which followed World War One. -

The Americanization of Edward Bok by Edward William Bok (1863-1930)

The Americanization of Edward Bok by Edward William Bok (1863-1930) The Americanization of Edward Bok by Edward William Bok (1863-1930) The Americanization of Edward Bok The Autobiography of a Dutch Boy Fifty Years After by Edward William Bok (1863-1930) To the American woman I owe much, but to two women I owe more, My mother and my wife. And to them I dedicate this account of the boy to whom one gave birth and brought to manhood and the other blessed with all a home and family may mean. An Explanation This book was to have been written in 1914, when I foresaw some leisure to write it, for I then intended to retire from active editorship. But the war came, an entirely new set of duties commanded, and the project was laid aside. page 1 / 493 Its title and the form, however, were then chosen. By the form I refer particularly to the use of the third person. I had always felt the most effective method of writing an autobiography, for the sake of a better perspective, was mentally to separate the writer from his subject by this device. Moreover, this method came to me very naturally in dealing with the Edward Bok, editor and publicist, whom I have tried to describe in this book, because, in many respects, he has had and has been a personality apart from my private self. I have again and again found myself watching with intense amusement and interest the Edward Bok of this book at work. I have, in turn, applauded him and criticised him, as I do in this book. -

Curtis Publishing Company Records Ms

Curtis Publishing Company records Ms. Coll. 51 Finding aid prepared by Margaret Kruesi. Last updated on April 07, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 1992 Curtis Publishing Company records Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Ladies' Home Journal Correspondence.................................................................................................10 Ladies' Home Journal Remittances.......................................................................................................11 -

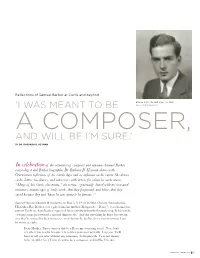

Reflections of Samuel Barber at Curtis and Beyond

Reflections of Samuel Barber at Curtis and beyond Barber in his student days, ca. 1932 ‘I WAS MEANT TO BE PHOTO: CURTIS ARCHIVES A COMPOSER, AND WILL BE I’M SURE.’ BY DR. BARBARA B. HEYMAN In celebration of the centenary of composer and alumnus Samuel Barber, musicologist and Barber biographer Dr. Barbara B. Heyman shares with Overtones reflections of his Curtis days and its influence on his career. She draws on his letters, his diaries, and interviews with artists for whom he wrote music. “Many of his Curtis classmates,” she writes, “generously shared with me treasured memories, manuscripts of early works that they performed, and letters that they saved because they just ‘knew he was going to be famous.’” Samuel Osmond Barber II was born on March 9, 1910, in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His father, Roy Barber, was a physician; his mother, Marguerite (“Daisy”), was an amateur pianist. Early on, Sam Barber expressed his creativity primarily through song. In his words, “writing songs just seemed a natural thing to do.” And the one thing he knew for certain was that he wanted to be a composer, an ambition he declared in a now-infamous letter he wrote at eight: Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don’t cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I suppose I will have to tell you now without any nonsense. To begin with, I was not meant to be an athlet [sic]. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I’m sure. -

Recital Programs 1930-1931

:'n ^i^)^ <' > ^ t>. List of Concerts and Operas Faculty Recitals First Miss Harriet van Emden, Soprano. .November 17, 1930 _ , (Miss Lucile Lawrence) becond. J >Harpists November 24, 1930 IMr. Carlos Salzedo / Third Mr. Mieczyslaw Munz, Pianist December 9, 1930 Fourth . .Madame Lea Luboshutz, Violinist December 16, 1930 Fifth Mr. Abram Chasins, Pianist January 8, 1931 Sixth Mr. Horatio Connell, Baritone January 12, 1931 Seventh . .Mr. Felix Salmond, Violoncellist January 19, 1931 Eighth Mr. Efrem Zimbalist, Violinist March 2, 1931 (Madame Isabelle Vengerova, Pianist) Ninth . .\ Madame Lea Luboshutz, Violinist, . /April 30, 1931 (^Mr. Felix Salmond, Violoncellist 1 Tenth Mr. Josef Hofmann, Pianist May 12, 1931 Special Concert The Musical Art Quartet March 11, 1931 1 1 Students' Concerts ("These programs, while listed alphabeticallji according to Instructor's name, are bound according to date.) pecember 10, 1930 Students of Mr. Bachmann <; (April 13, 1931 Chamber Music. April 14, 1931 I Students of Dr. Bailly in j ^.^j^ ^^^ ^g^ ^^3^ Students of Mr. Connell May 4, 1931 Students of Mr. de Gogorza April 27, 1931 ("January 14, 1931 Students of Mr. Hofmann < (Apnl 28, 1931 (November 12, 1930 Students of Madame Luboshutz <( (May 20, 1931 Students of Mr. Meiff March 30, 1931 Students of Mr. Salmond April 23, 1931 (March 25, 1931 Students of Mr. Salzedo < .. (April 1, 1931 Students of Mr. Saperton April 24, 193 Students of Madame Sembrich May 1, 1931 Students of Mr. Tabuteau May 5, 1931 Students of Mr. Torello April 16, 1931 Students of Miss van Emden May 15, 1931 (April 22, 1931 „ , r., w Students of Madame Vengerova < (May 19, 1931 Students of Mr. -

Of Music Endowed Mary Louise Curtis

CURT I S INST I T UTE of MUS I C En dowed MARY LOUISE CURTIS BOK CA TA L O G U E 1 92 8 - 1 929 RITTENHOUSE SQUARE PHILADELPHIA PENNSYLV ANIA THE C U RTIS INS TITU TE of MU S IC WAS E TE IN 1924 CR A D , , UNDE R AN E NDOWME NT By MARY LOUISE CURTIS BOK AND I S OPE RATE D UNDE R A CHARTE R OF THE COMMONWE ALTH OF PE NNS YLVANIA PURPOSE TO HAND DOWN THROUGH CONTE MPORARY MASTE RS THE GRE AT TRADI TIONS F THE S O PA T . TO TE ACH S TUDE NTS TO BUI LD ON THI S HE RITAGE FOR THE FUTURE P age F[we THE C U RTIS INS TITU TE of MU S IC OFFERS T o STUDENTS Instruction by world famous ar tis ts who give in dividual les sons . Free tuition . Financial aid , if needed . Steinway Grands , string and wind instruments rent free , to those unable to provide such for themselves . These Stein way pianos will be placed at the disposal of students in their respective domiciles . Opportunities to attend concerts of the Philadelphia Orchestra and of important visiting artists , also performances of the Metropolitan Opera Company— as part of their musical education . U ad Summer sojourns in the nited States and Europe , to van ce d and exceptionally gifted students , under artistic supervision of their respective master teachers of the Curtis Institute . u Public appearances during the period of their st dies , when o warranted by their progress , so that they may gain pra tical stage experience . -

“The Jazz Problem”: How U.S. Composers Grappled with the Sounds of Blackness, 1917—1925 Stephanie Doktor Cumming, Georgia

“The Jazz Problem”: How U.S. Composers Grappled with the Sounds of Blackness, 1917—1925 Stephanie Doktor Cumming, Georgia Bachelor of Arts, Vocal Performance, University of North Georgia, 2003 Master of Arts, Musicology, University of Georgia, 2008 Master’s Certificate, Women’s Studies, University of Georgia, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music University of Virginia December, 2016 iv © Copyright by Stephanie DeLane Doktor All Rights Reserved December 2016 v For Hillary Clinton and Terry Allen, who both lost the race but the fight still rages on vi ABSTRACT My dissertation tracks the development of jazz-based classical music from 1917, when jazz began to circulate as a term, to 1925, when U.S. modernism was in full swing and jazz had become synonymous with America. I examine the music of four composers who used black popular music regularly: Edmund Jenkins, John Powell, William Grant Still, and Georgia Antheil. For each composer, whose collections I consulted, I analyze at least one of their jazz-based compositions, consider its reception, and put it in dialogue with writings about U.S. concert music after World War I. Taken together, these compositions contributed to what I call the Symphonic Jazz Era, and this music was integral to the formation of American modernism. I examine how these four composers grappled with the sounds of blackness during this time period, and I use “the Jazz Problem” as an analytic to do so. This phrase began to circulate in periodicals around 1923, and it captured anxieties about both the rise of mass entertainment and its rootedness in black cultural sounds in the Jim Crow era. -

Thephiladelphia LAWYE Thephiladelphia LA

thePHILADELPHIA LAWYER thePHILADELPHIALAWYER Picture – Andrew Hamilton, the Original Philadelphia Lawyer “I think Philadelphia Lawyers tend to be competitive and combative, very much like the spirit of the town. There’s a feistiness here. It’s a town that tends to get its juices flowing. We’re not New York and we’re not Washington, so I think we’re forced to fight a little harder to get what we want. And we get it more often than not.”1 Quote by Ed Rendell, Former mayor of Philadelphia who became a governor of Pennsylvania Andrew Hamilton. Courtesy of Historical Society of Pennsylvania thePHILADELPHIA LAWYER 26 WHERE THE HECK AM I I N TH I S BI G BOOK ? THE PHILADELPHIA LAWYER NOTABLE STYLES thePHILADELPHIA LAWYER Sharp and Aggressive Fighters Tenacity Able To Handle All Aspects of Law Favor Freedom of Expression CONTENTS A Philadelphia Lawyer The Old Guard Early Lawsuits Early Twentieth Century Lawyers Big Firms, Old Names Venues Philadelphia’s Influences on the US Con- stitution Lawyers Portrayed Legal Writing Law and Race Women and the Philadelphia Bar Other Legends of the Bar Notable Judges American Bar Association Presidents Political Change New Areas of Practice Giving Back Portraits Cases - Civil Liberties Cases - Civil Cases Cases - Criminal Cases thePHILADELPHIA LAWYER OH, THERE I A M ! 27 A PHILADELPHIA LAWYER Philadelphia Lawyer: A song, Woody Guthrie’s “Philadelphia Lawyer” is named after this profession. An autobiography, George Wharton Pepper’s Philadelphia Lawyer, is named after it. A movie, Paul Newman’s The Young Philadelphians, is about lawyers in the title city. No other city’s lawyers are as identifiable by their geography.