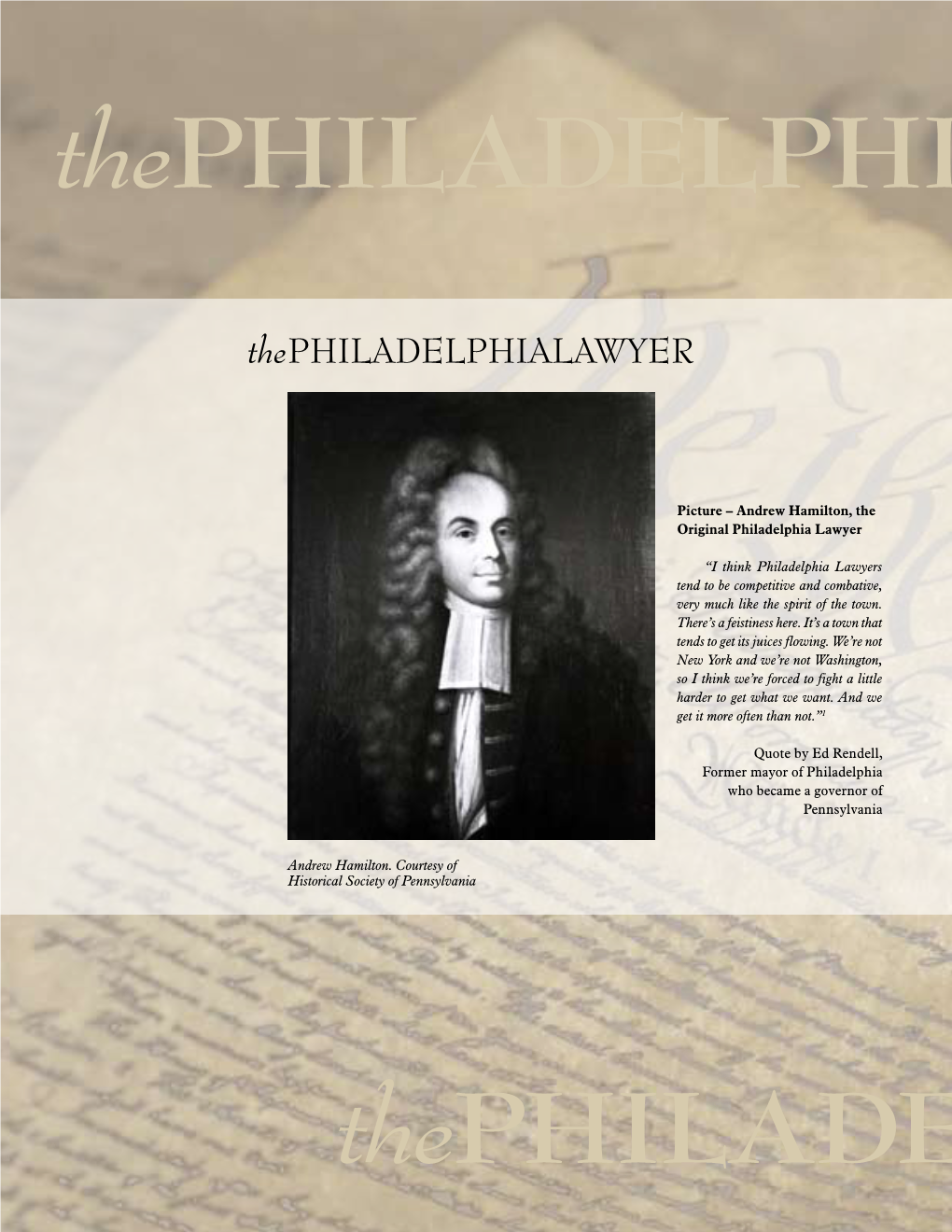

Thephiladelphia LAWYE Thephiladelphia LA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pennsylvania Assembly's Conflict with the Penns, 1754-1768

Liberty University “The Jaws of Proprietary Slavery”: The Pennsylvania Assembly’s Conflict With the Penns, 1754-1768 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the History Department in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts in History by Steven Deyerle Lynchburg, Virginia March, 2013 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Liberty or Security: Outbreak of Conflict Between the Assembly and Proprietors ......9 Chapter 2: Bribes, Repeals, and Riots: Steps Toward a Petition for Royal Government ..............33 Chapter 3: Securing Privilege: The Debates and Election of 1764 ...............................................63 Chapter 4: The Greater Threat: Proprietors or Parliament? ...........................................................90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................................................................113 1 Introduction In late 1755, the vituperative Reverend William Smith reported to his proprietor Thomas Penn that there was “a most wicked Scheme on Foot to run things into Destruction and involve you in the ruins.” 1 The culprits were the members of the colony’s unicameral legislative body, the Pennsylvania Assembly (also called the House of Representatives). The representatives held a different opinion of the conflict, believing that the proprietors were the ones scheming, in order to “erect their desired Superstructure of despotic Power, and reduce to -

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania's Connection to Slavery

Documenting the University of Pennsylvania’s Connection to Slavery Clay Scott Graubard The University of Pennsylvania, Class of 2019 April 19, 2018 © 2018 CLAY SCOTT GRAUBARD ALL RIGHTS RESERVED DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 2 OVERVIEW 3 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION 4 PRIMER ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 5 EBENEZER KINNERSLEY (1711 – 1778) 7 ROBERT SMITH (1722 – 1777) 9 THOMAS LEECH (1685 – 1762) 11 BENJAMIN LOXLEY (1720 – 1801) 13 JOHN COATS (FL. 1719) 13 OTHERS 13 LABOR AND CONSTRUCTION CONCLUSION 15 FINANCIAL ASPECTS 17 WEST INDIES FUNDRAISING 18 SOUTH CAROLINA FUNDRAISING 25 TRUSTEES OF THE COLLEGE AND ACADEMY OF PHILADELPHIA 31 WILLIAM ALLEN (1704 – 1780) AND JOSEPH TURNER (1701 – 1783): FOUNDERS AND TRUSTEES 31 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN (1706 – 1790): FOUNDER, PRESIDENT, AND TRUSTEE 32 EDWARD SHIPPEN (1729 – 1806): TREASURER OF THE TRUSTEES AND TRUSTEE 33 BENJAMIN CHEW SR. (1722 – 1810): TRUSTEE 34 WILLIAM SHIPPEN (1712 – 1801): FOUNDER AND TRUSTEE 35 JAMES TILGHMAN (1716 – 1793): TRUSTEE 35 NOTE REGARDING THE TRUSTEES 36 FINANCIAL ASPECTS CONCLUSION 37 CONCLUSION 39 THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 40 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 42 BIBLIOGRAPHY 43 DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 2 INTRODUCTION DOCUMENTING PENN’S CONNECTION TO SLAVERY 3 Overview The goal of this paper is to present the facts regarding the University of Pennsylvania’s (then the College and Academy of Philadelphia) significant connections to slavery and the slave trade. The first section of the paper will cover the construction and operation of the College and Academy in the early years. As slavery was integral to the economy of British North America, to fully understand the University’s connection to slavery the second section will cover the financial aspects of the College and Academy, its Trustees, and its fundraising. -

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: an Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1992 Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Frederick Lee Richards University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Richards, Frederick Lee, "Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991)" (1992). Theses (Historic Preservation). 349. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991). (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/349 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: An Architectural History and Inventory (1758-1991) Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Richards, Frederick Lee (1992). Old St. Peter's Protestant Episcopal Church, Philadelphia: -

Title IX Coordinator and Director, Human Resources and Equal Opportunity Musicians to Engage a Local and Global Community Throug

Title IX Coordinator and Director, Human Resources and Equal Opportunity The Curtis Institute of Music, a private school dedicated to the training and education of exceptionally gifted young musicians, invites nominations and applications for the position of Title IX Coordinator and Director, Human Resources and Equal Opportunity. The Curtis Institute seeks a strategic thinker and a relationship-driven community member who fosters productive collaborations, is trustworthy and approachable, and strives to serve as a valued and reliable resource to students, faculty, staff, and the administration. Serving as a newly added member of the President’s cabinet, the Director will oversee Curtis’s Title IX function and work in partnership with the Senior Associate Dean and Special Advisor to the President for Strategic Engagement, and members of the Ombuds Office to develop institutional equity initiatives across the campus. Reporting to the Senior Vice President of Administration, with a dotted line to the President & CEO, the Director will lead the division of Title IX, human resources, and equal opportunity services, and participate in a newly formed task force designed to support the well-being of students, staff, alumni, and faculty. The position will also have an open and confidential line to the Board of Trustees. This critical hire will be well-positioned to help Curtis remain true to its core mission: to educate and train exceptionally gifted young musicians to engage a local and global community through the highest level of artistry. 1 The Director will bring proficiency in both the current and emerging regulatory environments, as well as a deep understanding of national issues and trends as they relate specifically to Title IX and equal opportunity regulations. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

Archives and Special Collections

Archives and Special Collections Dickinson College Carlisle, PA COLLECTION REGISTER Name: Price, Eli Kirk (1797-1884) MC 1999.13 Material: Family Papers (1797-1937) Volume: 0.75 linear feet (Document Boxes 1-2) Donation: Gift of Samuel and Anna D. Moyerman, 1965 Usage: These materials have been donated without restrictions on usage. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Eli Kirk Price was born near Brandywine in Chester County, Pennsylvania on July 20, 1797. He was the eighth of eleven children born to Rachel and Philip Price, members of the Society of Friends. Young Eli was raised within the Society and received his education at Westtown Boarding School in West Chester, Pennsylvania. After his years at Westtown, Price obtained his first business instruction in the store of John W. Townsend of West Chester. In 1815 Price went on to the countinghouse of Thomas P. Cope of Philadelphia, a shipping merchant in the Liverpool trade. While in the employ of Cope, Price familiarized himself with mercantile law and became interested in real estate law. In 1819 he began his legal studies under the tutelage of the prominent lawyer, John Sergeant of Philadelphia, and he was admitted to the Philadelphia Bar on May 28, 1822. On June 10, 1828 Price married Anna Embree, the daughter of James and Rebecca Embree. Together Eli and Anna had three children: Rebecca E. (Mrs. Hanson Whithers), John Sergeant, and Sibyl E (Mrs. Starr Nicholls). Anna Price died on June 4, 1862, a year and a half after their daughter Rebecca had died in January 1861. Price’s reputation as one of Philadelphia’s leading real estate attorneys led to his involvement in politics. -

SUMMER | 2021 Lawyering in the Age of Covid-19 Lawyering in Theageof American College of Trial Lawyers JOURNAL

ISSUE 96 | SUMMER | 2021 Lawyering in theageof Covid-19 American College of Trial Lawyers JOURNAL Chancellor-Founder Hon. Emil Gumpert contents (1895-1982) 02 04 05 OFFICERS Letter from the Editor Annual Meeting President’s The College RODNEY ACKER President Announcement Perspective Welcomes New MICHAEL L. O’DONNELL President-Elect Officers & Regents SUSAN J. HARRIMAN Treasurer WILLIAM J. MURPHY Secretary DOUGLAS R. YOUNG Immediate Past President MEETING RECAP BOARD OF REGENTS 09 15 19 25 RODNEY ACKER DAN S. FOLLUO CLE: The 25th Anniversary The Honorable Brian Brurud - Check 6 Scientific Collaboration in Dallas, Texas Tulsa, Oklahoma of the VMI Case: Mark E. Recktenwald – Access to The Fight Against Covid-19 PETER AKMAJIAN LARRY H. KRANTZ Remembering RBG Justice In the Age Of COVID Tucson, Arizona New York, New York SUSAN S. BREWER MARTIN F. MURPHY Morgantown, West Virginia Boston, Massachusetts JOE R. CALDWELL, JR. WILLIAM J. MURPHY Washington, D.C. Baltimore, Maryland 31 37 41 47 JOHN A. DAY MICHAEL L. O’DONNELL Brentwood, Tennessee Denver, Colorado The Importance of Dr. Patrick Connor — A Conversation With Never Out Of The Fight — Separate Opinions — Treating Panthers the Former President the Eddie Gallagher RICHARD H. DEANE, JR. LYN P. PRUITT Professor Melvin Urofsky of the United States Court Martial Atlanta, Georgia Little Rock, Arkansas MONA T. DUCKETT, Q.C. JEFFREY E. STONE Edmonton, Alberta Chicago, Illinois GREGORY M. LEDERER MICHAEL J. SHEPARD Cedar Rapids, Iowa San Francisco, California 53 59 65 67 Michele Bratcher Goodwin Defending the Skies — Heather Younger — Spring 2021 SANDRA A. FORBES CATHERINE RECKER — Quarantine: The Reach and General Victor Eugene Building Resistence Induction Ceremony Toronto, Ontario Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Limits of Government Action Renuart, Jr. -

In a Lonely Place Arlen Specter Is the Same. It's the GOP That's Changed

WEEK OF NOVEMBER 22, 2004 In A Lonely Place Arlen Specter is the same. ROBERTO WESTBROOK ROBERTO It’s the GOP that’s changed. BY T.R. GOLDMAN staff member was now 14 months away from being the longest serving senator in the history of Pennsylvania—after fellow The harsh glare of the single television spotlight made Arlen Republican Boise Penrose, who died in office on Dec. 31, 1921. Specter’s face shine unnaturally, and his smile was tight and He had survived a grueling primary against Rep. Patrick prearranged. Toomey (R-Pa.), and an unexpectedly tough general election The disembodied voice of CNBC’s Gloria Borger was work- against Rep. Joseph Hoeffel (D-Pa.). ing its way into Specter’s ear. Behind him, the rotunda of the But when Specter takes over the Senate Judiciary Committee Senate’s Russell Building glowed in the sunset. in January, as he now appears certain to do, he will be noted The conversation had turned to Richard Viguerie, the arch- more for surviving an infelicitous remark at a euphoric Nov. conservative direct mail guru, and one of those most promi- 3 press conference—that it was “unlikely” that the committee nently opposing the Pennsylvania Republican’s ascension to the would confirm any judicial nominee who would overturn Roe chairmanship of the Senate Judiciary Committee. v. Wade—than for possessing what his supporters say is a long “I’m not about to make any deals with Richard Viguerie,” and distinguished career as one of the Senate’s few remaining said Specter, his eyes blinking with intensity. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HORACE BINNEY AND THE WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS: A NEW VIEW JORDAN TOBE SPRING 2014 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in History and English with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Neely McCabe Greer Professor in the American Civil War Era Thesis Supervisor Michael Milligan Senior Lecturer in History, Honors History Advisor Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The constitutionality of President Abraham Lincoln’s suspension the writ of habeas corpus during the American Civil War has been widely discussed and debated throughout Civil War history. In this history, the defense of Lincoln’s actions by one prominent Philadelphia lawyer, Horace Binney, usually gets only a brief mention. Somewhere in their quick overviews of Horace Binney’s habeas corpus argument, however, historians have ignored important information. For one thing, Binney’s political and personal background, which has not been widely discussed, lays a noteworthy foundation for his habeas corpus argument. Additionally, Binney’s argument was provoking enough that it elicited dozens of responses from his political opponents, Democratic lawyers. These Democratic responses have been more or less neglected in historiography. This project aims not only to delve deeper into why Binney argued in defense of the president the way that he did, but also to analyze the responses from his -

Chapter 2: Above the Roof: Exquisite Miniature

Above the Roof 35 Figure 1 18th Century Engraving of Philadelphia Skyline, Nicholas Scull engraver Chapter 2: Above the Roof: Exquisite Miniature The late Alfred Kazin, one of New York’s intelligentsia, mused as he looked out the window toward the city, “I feel I am dreaming aloud as I look at the rooftops, at the sky, at the massed white skyline of New York. The view across the rooftops is as charged as the indented black words on the white page. The mass and pressure of the bulging skyline are wild.”1 As ships at sea, as inscriptions on a page, yet full as the body of an animal, wild, the city skyline revealed the “beautiful bedlam and chaos of New York” in a profile that flattens the mass of buildings into a cipher. The same buildings when seen from below and close at hand, thicken into squat forms distorted by foreshortening. Vitruvius acknowledged the mutability of scale in the design of upper story columns or sculpture, recommending that they be elongated proportionally so they would not appear to be pitching forward.2 He also advised reducing the upper tier of military towers by one fifth so they would not seem top-heavy when seen from below. The smaller and taller proportions of aerial architecture take into account the position of a viewer, addressing the eye more than the body. Alberti towers are excellent ornament In the 15th century, Leon Battista Alberti wrote that watchtowers were “an excellent ornament” for the profile of a building. He proposed exaggerating the apparent height through a proportional reduction in the size of each successive tier of a tower. -

Family Surnames of Value in Genealogical Research Are Printed in CAPITALS; Names of Places in Italics

INDEX (Family surnames of value in genealogical research are printed in CAPITALS; names of places in italics) Abercrombie, Reverend James, Assis- Baltimore, agreement of merchants tant Rector of Christ Church (fac- of, to suspend trade with England, ing), 312 366 Adams, Charles Francis, 356 Barbados Gazette, published by Adams, Captain James, of the ship Samuel Keimer, 283-287 Elliot, 81 Barber, Edwin Atlee, 119 Adams, John, 356 Barclay, E. E., publisher, 149, 150 Adams, John Quincy, 320 Barnhart Family, query regarding, by Adams, Samuel, opposed to adoption Nat G. Barnhart. 384 of the Constitution by Massachu- Barnum, Mr. , dinner for setts, 201 Washington Celebration, Second Addison* Judge Alexander, 335 Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry, Ainsworth, William Harrison, 134 67 Alcott, A. Bronson, 132, 136 Barrett, Gyles, 216 Alexander, Major , 168 Bartram, Alexander, potter, Philadel- ALLEN, MARY, 43 phia, 100, 112, 113; advertise- ALLEN, NATHANIEL, 43 ments of, 112; property of, 112, Allen, Sergeant Samuel, 62, 72, 73, 113 ; estate of, 1779, 113 77. 78, 178, 375, 376 BARTRAM, ALZIRA, 82 America, The, arrives, 1683, 98. 100 BARTRAM, ANN, 82 American Courier, The, 151 BARTRAM, ANNA MARIA, 82 Ames, Herman V., Franklin, The BARTRAM, CATHARINE, 82 Apostle of Modern Times, by Ber- BARTRAM, ELIZABETH, 81 nard Fay, notice of, by, 188-190 Bartram, Col. George, 74, 75 Andros, Governor Edmund, 214. 243 BARTRAM, GEORGE WASHING- Anthony, Joseph, silversmith, Phila- TON, 81, 82 delphia, 110 Bartram, George Washington, bio- Arnold, General Benedict, 195 ; with graphical note, 81, 82 forces blocked up in James River, BARTRAM, GEORGIANA MARIA, Virginia, 164 82 Arskin, Jonas, 216 BARTRAM, HENRY.