Shabir Ahmad Bhat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brief District Profile District Anantnag Is One of the Oldest Districts of The

District at a Glance Brief District Profile District Anantnag is one of the oldest districts of the valley and covered the entire south Kashmir before its bifurcation into Anantnag and Pulwama in 1979. The districts of Anantnag and Pulwama later got sub-divided into Kulgam and Shopian, in 2007. The districts of Pulwama and Kulgam lie on the north and north-west of District Anantnag, respectively. The district of Ganderbal and Kargil touch its eastern boundary and the district of Kishtawar meets on its southern boundary whileas District Doda touches its west land strip. The population of the district, as per census 2011, is 1078692 (10.79 lac) souls, comprising of 153640 households, with a gender distribution of 559767 (5.60 lac) males and 518925 (5.19 lac) females and as per the natural arrangement the district has 927 females against 1000 males while as it is 1000:889 at the state level. The Rural, Urban constitution of the populations stands in the ratio of 74:26 as against 73:27 for the state. 1 District at a Glance The district consists of 386 inhabited and 09 un-inhabited revenue villages. Besides, there is one Municipal Council and 09 Municipal Committees in the district. The district consists of 12 tehsils, viz, Anantnag, Anantnag-East, Bijbehara, Dooru, Kokernag, Larnoo, Pahalgam, Qazigund, Sallar, Shahabad Bala, Shangus and Srigufwara with four sub-divisions viz Bijbehara, Kokernag, Dooru and Pahalgam. The district is also divided into 16 CD blocks, viz, Achabal, Anantnag, Bijbehara, Breng, Chhittergul, Dachnipora, Hiller Shahabad, Khoveripora, Larnoo, Pahalgam, Qazigund, Sagam, Shahabad, Shangus, Verinag and Vessu for ensuring speedy and all-out development of rural areas. -

Restoration of Springs Around Manasbal Lake

INTACH Jammu & Kashmir Chapter I Vol: 3 I Issue: 14I Month: July, 2018 Restoration of springs around Manasbal Lake Photo: Ongoing restoration of spring around Manasbal Lake, Ganderbal (INTACH 2018). As part of its natural heritage conservation program, INTACH Kashmir takes up restoration of springs around Manasbal Lake as a pilot. In the initial phase of restoration drive, 50 springs were restored around the lake. The life line of any community is water. In Kashmir, nature has bestowed with a rich resource of water in the form of lakes, rivers and above all springs. These springs were a perennial water source for local communities. Unfortunately most and a large number of these springs are facing extinction due to neglect which results water shortages in villages and at some places we have water refugees or climate migrants. The springs are critical part of our survival and needs to be preserved. Keeping in view the importance of preservation of these natural resources which is our natural heritage also, INTACH Kashmir initiated a drive to the springs around Manasbal lake which are on the verge of extinction. restore the springs. A local NGO from There was an overwhelming response from the local inhabitants during the dis trict Ganderbal, Heeling Touch Foundation is involved to identify restoration process. 1 I N D I A N N A T I O N A L T R U S T F O R A R T & C U L T U R A L H E R I T A G E INTACH Jammu & Kashmir Chapter I Vol: 3 I Issue: 14I Month: July, 2018 RESTORATION OF SPRINGS AROUND MANASBAL LAKE 2 I N D I A N N A T I O N A L T R U S T F O R A R T & C U L T U R A L H E R I T A G E INTACH Jammu & Kashmir Chapter I Vol: 3 I Issue: 14I Month: July, 2018 INTACH Jammu celebrates Vanmohatsav festival, plants Chinar saplings INTACH Jammu Chapter, in collaboration with Floriculture Department, Jammu Municipal Corporation and local residents celebrated “VANMAHOTSAV” on 11th July 2018. -

June Ank 2016

The Specter of Emergency Continues to Haunt the Country Mahi Pal Singh Forty one years ago this country witnessed people had been detained without trial under the the darkest chapter in the history of indepen- repressive Maintenance of Internal Security Act dent and democratic India when the state of (MISA), several high courts had given relief to emergency was proclaimed on the midnight of the detainees by accepting their right to life and 25th-26th June 1975 by Indira Gandhi, the then personal liberty granted under Article 21 and ac- Prime Minister of the country, only to satisfy cepting their writs for habeas corpus as per pow- her lust for power. The emergency was declared ers granted to them under Article 226 of the In- when Justice Jagmohanlal Sinha of the dian constitution. This issue was at the heart of Allahabad High Court invalidated her election the case of the Additional District Magistrate of to the Lok Sabha in June 1975, upholding Jabalpur v. Shiv Kant Shukla, popularly known charges of electoral fraud, in the case filed by as the Habeas Corpus case, which came up for Raj Narain, her rival candidate. The logical fol- hearing in front of the Supreme Court in Decem- low up action in any democratic country should ber 1975. Given the important nature of the case, have been for the Prime Minister indicted in the a bench comprising the five senior-most judges case to resign. Instead, she chose to impose was convened to hear the case. emergency in the country, suspend fundamen- During the arguments, Justice H.R. -

*‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups

T5 Table[5.[Ethnic[and[National[Groups T5 T5 TableT5[5. [DeweyEthnici[Decimaand[NationalliClassification[Groups T5 *‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 089 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., civil and political rights (323.11) of Navajo Indians (—9726 in this table): 323.119726; ceramic arts (738) of Jews (—924 in this table): 738.089924. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 174 from Table 2 In this table racial groups are mentioned in connection with a few broad ethnic groupings, e.g., a note to class Blacks of African origin at —96 Africans and people of African descent. Concepts of race vary. A work that emphasizes race should be classed with the ethnic group that most closely matches the concept of race described in the work Except where instructed otherwise, and unless it is redundant, add 0 to the number from this table and to the result add notation 1 or 3–9 from Table 2 for area in which a group is or was located, e.g., Germans in Brazil —31081, but Germans in Germany —31; Jews in Germany or Jews from Germany —924043. If notation from Table 2 is not added, use 00 for standard subdivisions; see below for complete instructions on using standard subdivisions Notation from Table 2 may be added if the number in Table 5 is limited to speakers of only one language even if the group discussed does not approximate the whole of the -

Contribution of British Rule in Kashmir

[VOLUME 6 I ISSUE 2 I APRIL – JUNE 2019] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 Contribution of British Rule in Kashmir 1Mubarik Ahmad Itoo & 2M. C. Dubey & 3 Subzar Ahmad Bhat 1Research Scholar 2Assistant Prof. Department of History, Mewar University, Rajasthan. 3Research Scholor 1Mewar University, Chittorgarh, Rajasthan. Received: February 18, 2019 Accepted: March 21, 2019 ABSTRACT: There is a common perception that British rule resulted in poverty, de industrialization etc in India. But as for as princely state of Jammu and Kashmir is concerned the British intervention resulted in positive outcomes. The British intervention resulted in modernization of various fields of Jammu and Kashmir. The introduction of modern education, land settlements ,modern health care, transportation etc. where the outcomes of British intervention. This paper highlights that British intervention resulted in modernization of Jammu and Kashmir not only in short run but in long run. Key Words: INTRODUCTION Once British became absolute political power in the Indian sub-continent, there policy towards princely states remained of two type’s i.e., direct and indirect policy. Direct policy was promoted towards the states which were directly ruled by British through their governors and indirect policy was conceded towards the states, ruled indirectly by British through their residents. The preference to bring a state under direct or indirect policy was mostly determined by state’s geography and economic resources. British annexed Punjab in 1846 and Kashmir being part of Lahore Darbar also came under the suzerainty of British. But at that time fate of Kashmir was determined by the need of time when British found sale of Kashmir inevitable because Punjab was yet to consolidate and North-West Frontier and Afghanistan unsettled. -

Jammu and Kashmir Directorate of Information Accredited Media List (Jammu) 2017-18 S

Government of Jammu and Kashmir Directorate of Information Accredited Media List (Jammu) 2017-18 S. Name & designation C. No Agency Contact No. Photo No Representing Correspondent 1 Mr. Gopal Sachar J- Hind Samachar 01912542265 Correspondent 236 01912544066 2 Mr. Arun Joshi J- The Tribune 9419180918 Regional Editor 237 3 Mr. Zorawar Singh J- Freelance 9419442233 Correspondent 238 4 Mr. Ashok Pahalwan J- Scoop News In 9419180968 Correspondent 239 0191-2544343 5 Mr. Suresh.S. Duggar J- Hindustan Hindi 9419180946 Correspondent 240 6 Mr. Anil Bhat J- PTI 9419181907 Correspondent 241 7 S. Satnam Singh J- Dainik Jagran 941911973701 Correspondent 242 91-2457175 8 Mr. Ajaat Jamwal J- The Political & 9419187468 Correspondent 243 Business daily 9 Mr. Mohit Kandhari J- The Pioneer, 9419116663 Correspondent 244 Jammu 0191-2463099 10 Mr. Uday Bhaskar J- Dainik Bhaskar 9419186296 Correspondent 245 11 Mr. Ravi Krishnan J- Hindustan Times 9419138781 Khajuria 246 7006506990 Principal Correspondent 12 Mr. Sanjeev Pargal J- Daily Excelsior 9419180969 Bureau Chief 247 0191-2537055 13 Mr. Neeraj Rohmetra J- Daily Excelsior 9419180804 Executive Editor 248 0191-2537901 14 Mr. J. Gopal Sharma J- Daily Excelsior 9419180803 Special Correspondent 249 0191-2537055 15 Mr. D. N. Zutshi J- Free-lance 88035655773 250 16 Mr. Vivek Sharma J- State Times 9419196153 Correspondent 251 17 Mr. Rajendra Arora J- JK Channel 9419191840 Correspondent 252 18 Mr. Amrik Singh J- Dainik Kashmir 9419630078 Correspondent 253 Times 0191-2543676 19 Ms. Suchismita J- Kashmir Times 9906047132 Correspondent 254 20 Mr. Surinder Sagar J- Kashmir Times 9419104503 Correspondent 255 21 Mr. V. P. Khajuria J- J. N. -

Census of India, 1931

·. ---~ . Census of India, 1931 VOL. I-INDIA Part 1--Report • by J. H. HUTTON, C.J.E., D.Sc., F.A.S.B., Carreapoacllaa Me1nber of the Anthropologieche Gesell-chait of Vlama To which ia annexed an ACTUARIAL REPORT by L S. Vaidyanathan, F. I. A. DELHI: MANAGRR OF' PUBLICATION8 1933 Governmen~ of In~~ ~blications are _obtainable from the Manager of Publica tions, Ctvil Lmes, Old Delhi, a.nd from the following Agents :- EUROPE. U-45.2.St') OJ' OniCE THE HIGH COMMISSIONER F0R INDIA, G1 lNDIA HousE, ALDwYCH, LONDON, W. C. 2. v l• I And at all Booksellers. INDIA AND CEYLON : Provincial Book Depots. 16$l6 2.. ..IAJ,f:Ml :..:._Superintet•dent, Government Press, Mount Road, Madras liOltlHY :--:-.Superir.tendent, Go;-crnment Print ,ng and Stationery, Queen's Road, Bombay. StNL> :- -Ltbrary attad1ed to the Oflice of the Commissioner in Sind, Karachi. H!!:I>'i.\L :-Bengal :-iecretariat Book Deput. Writers' Buildings, Room No. 1, Ground Floor, Calcutta. UNJTEJJ PrrovJ:;CEs OF MRA AND OuDH :-.Superintendent of Government Press, United Provinces of ARra and Oudh, Allahabad. PUNJAB :-Superintendent, Govemment Printing, Punjab, Lahore. BURMA :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, Rangoon. CENTRAL PROVINCES ANL> BERAR :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Central Provinces Nagpur. '.\.ssAM :-Superintendent, Assam Secretariat Press, Shillong. ' BJHAn AND ORISSA :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Bihar altd Orissa, P. 0. Gu!,.u·bagh Patna. NoRTH-\\TE.ST FRONTIER PROVJNC£ :-Manager, Goverument Printing and Stationery, Pe:;haw~. Thacker Spink & Co., Ltd., Calcutta and Simla. The :::\tudents Own Rook Depot, Dharwar. W. Newman & Co., Ltd., Calcutta. Shri Shankar Karnataka Pustal-"a Bhandara, Mala- 8. K. -

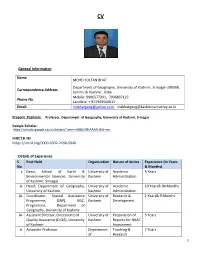

General Information Name MOHD SULTAN BHAT Correspondence Address Department of Geography, University of Kashmir, Srinagar-19000

CV General Information Name MOHD SULTAN BHAT Department of Geography, University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006, Correspondence Address Jammu & Kashmir, India Mobile: 9906577391, 7006837122 Phone No. Landline: + 911943560615 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Present Position: Professor, Department of Geography, University of Kashmir, Srinagar Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.co.in/citations?user=yHBbV9EAAAAJ&hl=en ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2198-5940 Details of Experience S Post Held Organization Nature of duties Experience (In Years No. & Months) i. Dean, School of Earth & University of Academic 3 Years Environmental Sciences, University Kashmir Administration of Kashmir, Srinagar ii. Head, Department of Geography, University of Academic 10 Years& 04 Months University of Kashmir Kashmir Administration iii. Coordinator, Special Assistance University of Research & 2 Years& 9 Months Programme, (SAP), UGC, Kashmir Development Programme, Department of Geography, University of Kashmir iv. Assistant Director, Directorate of University of Preparation of 3 Years Quality Assurance (DIQA), University Kashmir Reports for NAAC of Kashmir Assessment v. Associate Professor Department Teaching & 7 Years of Research 1 Geography, University of Kashmir vi. Assistant Professor Department Teaching & 13 Years of Research Geography , University of Kashmir Educational Qualification S. No. Qualification University Year i. Ph. D University of Kashmir 1995 ii. M. Phil University of Kashmir 1989 iii. Post-Graduation University of Kashmir 1986 Administrative Experience/Post(s) &Responsibilities held S Post Organization/ Duration No. University From To (Date) (Date) i. Head of the Department of Geography , University of 01.07.20006 04-02-2014 Department Kashmir & 05-02-2017 09-09-2019 ii. Chairman, Chairman Board of Postgraduate 01.07.20006 04-02-2014 Board of Studies, Department of Geography, & Studies University of Kashmir 05-02-2017 09-09-2019 iii. -

History, University of Kashmir

Post Graduate Department of History University of Kashmir Syllabus For the Subject History At Under-Graduate Level Under Semester System (CBCS) Effective from Academic Session 2016 Page 1 of 16 COURSE CODE COURSE TITLE SEMESTER CORE PAPERS CR-HS-I ANCIENT INDIA/ANCIENT FIRST KASHMIR CR-HS-II MEDIEVAL SECOND INDIA/MEDIEVAL KASHMIR CR-HS-III MODERN INDIA/MODERN THIRD KASHMIR CR-HS-IV THEMES IN INDIAN FOURTH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY DISCIPLINE SPECIFIC ELECTIVES DSE-HS-I HISTORY OF INDIA SINCE FIFTH 1947 DSE-HS-II HISTORY OF THE WORLD FIFTH (1945-1992) DSE-HS-III THEMES IN WORLD SIXTH CIVILIZATION DSE-HS-IV WOMEN IN INDIAN SIXTH HISTORY GENERIC ELECTIVES GE-HS-I (THEMES IN HISTORY-I) FIFTH GE-HS-II (THEMES IN HISTORY – II) SIXTH SKILL ENHANCEMENT COURSES SEC-HS-I ARCHAEOLOGY: AN THIRD INTRODUCTION SEC-HS-II HERITAGE AND TOURISM FOURTH IN KASHMIR SEC-HS-III ARCHITECTURE OF FIFTH KASHMIR SEC-HS-IV ORAL HISTORY: AN SIXTH INTRODUCTION Page 2 of 16 CR-HS-I (ANCIENT INDIA/ANCIENT KASHMIR) UNIT-I (Pre and Proto History) a) Sources] i. Archaeological Sources: Epigraphy and Numismatics ii. Literary Sources: Religious, Secular and Foreign Accounts b. Pre and Proto History: Paleolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic Cultures: Features. c. Chalcolithic Cultures: Features d. Harappan Civilization: Emergence, Features, Decline, Debate. UNIT-II (From Vedic to Mauryas) a) Vedic Age i. Early Vedic Age: Polity, Society. ii. Later-Vedic Age: Changes and Continuities in Polity and Society. b) Second Urbanization: Causes. c) Janapadas, Mahajanapadas and the Rise of Magadh. d) Mauryas: Empire Building, Administration, Architecture; Decline of the Mauryan Empire (Debate). -

Khir Bhawani Temple

Khir Bhawani Temple PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship Page Intentionally Left Blank ii KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)). PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship KKaasshhmmiirr:: TThhee PPllaacceess ooff WWoorrsshhiipp First Edition, August 2002 KASHMIR NEWS NETWORK (KNN)) iii PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com PDF created with FinePrint pdfFactory Pro trial version www.pdffactory.com Kashmir: The Places of Worship Contents page Contents......................................................................................................................................v 1 Introduction......................................................................................................................1-2 2 Some Marvels of Kashmir................................................................................................2-3 2.1 The Holy Spring At Tullamulla ( Kheir Bhawani )....................................................2-3 2.2 The Cave At Beerwa................................................................................................2-4 2.3 Shankerun Pal or Boulder of Lord Shiva...................................................................2-5 2.4 Budbrari Or Beda Devi Spring..................................................................................2-5 2.5 The Chinar of Prayag................................................................................................2-6 -

District Census Handbook, Srinagar, Parts X-A & B, Series-8

CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A & B TOWN & VILLAGE DIRECTORY SERIES-8 JAMMU & KASHMIR VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS .. ABSTRACT SRINAGAR DISTRICT DISTRICT 9ENSUS . ~')y'HANDBOOK J. N. ZUTSHI of the Kashmir Administrative Service Director of Census Operations Jammu and Kashmir '0 o · x- ,.,.. II ~ ) "0 ... ' "" " ._.;.. " Q .pi' " "" ."" j r) '" .~ ~ '!!! . ~ \ ~ '"i '0 , III ..... oo· III..... :I: a:: ,U ~ « Z IIJ IIJ t9 a: « Cl \,.. LL z_ UI ......) . o ) I- 0:: A..) • I/) tJ) '-..~ JJ CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS Central Government Publications-Census of India 1971-Series 8-Jammu & Kashmir is being Published in the following parts. Number Subject Covered Part I-A General Report Part I-B General Report Part I-C Subsidiary Tables Part II-A General Population Tables Part JI-B Economic Tables Part II-C(i) Population by Mother Tongue, Religion, Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes. Part II-C(ii) Social & Cultural Tables and Fertility Tables Part III Establishments Report & Tables Part IV Housing Report and Tables Part VI-A Town Directory Part VI-B Special Survey Reports on Selected Towns Part VI-C Survey Reports on Selected Villages Part VIII-A Administration Report on Enumeration Part VIII-B Administration Report on Tabulation Part IX Census Atlas Part IX-A Administrative Atlas Miscellaneous ei) Study of Gujjars & Bakerwals (ii) Srinagar City DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOKS Part X-A Town & Village Directory Part X-B Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract Part X-C Analytical Report, Administrative Statistics & District Census Table!! -

1000+ Question Series PDF -Jklatestinfo

JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q1) The kashmir Valley was originally a huge lake called ? a) Manesar b) Neelam c) Satisar d) Both ‘b’ & ‘c’ Q2) Kalhana , a famous historian wrote ? a) Nilmatpurana b) Rajtarangini c) Both d) None of these Q3) The First king mentioned by Kalhana is ? a) Gonanda I b) Durlabha Vardhana c) Ashoka d) Jalodbhava Q4) The outer plains doesn’t cover which of the following ? a) RS Pura b) Kathua c) Akhnoor d) Udhampur Q5) When J&K became Union Territory ? a) August 5, 2019 b) October 31, 2019 c) September 5, 2019 d) October 1 , 2019 JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q6) Which among the following is the welcome dance for spring season ? a) Bhand Pathar b) Dhumal c) Kud d) Rouf Q7) Total number of districts in J&K ? a) 22 b) 21 c) 20 d) 18 Q8) On which hill the Vaishno Devi Mandir is located ? a) Katra b) Trikuta c) Udhampur d) Aru Q9) The SI unit of charge is ? a) Ampere b) Coulomb c) Kelvin d) Watt Q10) The filament of light bulb is made up of ? a) Platinum b) Antimony c) Tungsten d) Tantalum JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/ Q11) Battle of Plassey was fought in ? a) 1757 b) 1857 c) 1657 d) 1800 Q12) Indian National Congress was formed by ? a) WC Bannerji b) George Yuli c) Dada Bhai Naroji d) A.O HUme Q13) The Tropic of cancer doesn’t pass through ? a) MP b) Odisha c) West Bengal d) Rajasthan Q14) Which of the following is Trans-Himalyan River ? a) Ganga b) Ravi c) Yamuna d) Indus Q15) Rovers cup is related to ? a) Hockey b) Cricket c) Football d) Cricket JKLATEST INFO https://jklatestinfo.com/