Mascarenhas, Mira. 2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

South-Goa-Map-Of-Ideal-Villages

SOUTH GOA MAP OF N DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT N IDEAL VILLAGES MAP OF SOUTH GOA CANDOLA BY GOA PRIs UNION W E CANDOLA BY GOA PRIs UNION W E ORGAO ORGAO BETQUI CURTORIM BETQUI CURTORIM TIVREM TIVREM VOLVAI S 2 VOLVAI S ADCOLNA K ADCOLNA K BOMA SAVOI-VEREM A BOMA SAVOI-VEREM A CUNCOLIM CUNCOLIM R R GANGEM GANGEM QUERIM VAGURBEM QUERIM VAGURBEM CUNDAIM CUNDAIM SURLA 1 SURLA N 4 N USGAO USGAO PRIOL PRIOL VELINGA CANDEPAR AGLOTE A VELINGA CANDEPAR AGLOTE A MARCAIM MARCAIM 3 CURTI T CURTI T PILIEM PILIEM BANDORA BANDORA MOLEM A PONDA MUNICIPALITY MOLEM A MORMUGAO PONDA SANCORDEM MORMUGAO MUNICIPALITY 5 SANCORDEM CHICALIM DARBANDORA DARBANDORA CHICALIM 24 QUELOSSIM QUELOSSIM P O N D A CODAR K P O N D A CODAR K DURBHAT QUELA 25 DURBHAT QUELA BETORA BETORA M O R M U G A OSANCOALE TALAULIM M O R M U G A OSANCOALE TALAULIM ISSORCIM D A R B A N D O R A A ISSORCIM D A R B A N D O R A A VADI VADI 6 18 S S PALE PALE CHICOLNA NIRANCAL CHICOLNA NIRANCAL CUELIM NAGOA BORIM CUELIM NAGOA BORIM CARANZOL CARANZOL SANGOD SANGOD VELSAO Xref CODLI T VELSAO Xref CODLI T LOUTULIM COLLEM LOUTULIM COLLEM CANSAULIM CONXEM CANSAULIM CONXEM VERNA VERNA CODLI A A 8 CODLI AROSSIM AROSSIM SIGAO 9 SIGAO SHIRODA SHIRODA CAMURLIM T CAMURLIM T UTORDA C0RMONEM UTORDA C0RMONEM MAJORDA CAMORCONDA MAJORDA 7 CAMORCONDA NUVEM SONAULI NUVEM SONAULI CALATA RACHOL CALATA RACHOL GONSUA E GONSUA E RAIA BANDOLI 10 RAIA BANDOLI MOISSAL MOISSAL BETALBATIM CALEM BETALBATIM 17 CALEM ARABIAN DUNCOLIM BOMA ARABIAN DUNCOLIM BOMA MACASANA SANTONA MACASANA SANTONA GAUNDAULIM GAUNDAULIM CURTORIM RUMBEREM -

SSC Result Booklet April-May 2020

Goa Board of Secondary & Higher Secondary Education Alto Betim-Goa APRIL-MAY 2020 Result Tuesday, 28th July, 2020 Certified that the Result of SSC Exam. April-May 2020 is prepared as per the rules of the Board in force. (Bhagirath G. Shetye) Secretary To be published strictly after 04.30 p.m. on 28th July, 2020 76 1 INDEX Sr.No. Particulars Page No. I Performance Report 3 II List of the Schools with Cent 4 Percent Results III School-wise Performance of 10 Candidates (at Glance) IV Centre-wise Performance of 33 candidates V Centre-wise Result 37 2 I. PERFORMANCE REPORT The SSC Examination was re-scheduled from 21st May, 2020 to 6th June, 2020 at 29 examination centres across the state, due to pandemic situation. A total of 18939 candidates registered under whole category (without exemption) for the SSC Examination of April-May, 2020. Out of 18939 candidates 17554 candidates pass the SSC Examination of April-May 2020 giving pass percentage of 92.69%. A total of 737 candidates registered under repeater/ITI category for the SSC Examination of April-May, 2020. Out of 737 candidates 345 candidates pass SSC Examination of April-May 2020 giving pass percentage of 46.81%. Result at a glance (Regular candidates): Appeared Passed Pass % Boys 9319 8581 92.08 Girls 9620 8973 93.27 Total 18939 17554 92.69 Highest and Lowest Pass Percentage centres Name of the Centre Enrollment Pass % Mangueshi 258 98.06 (Highest) Kepem 441 86.85 (Lowest) Highest and Lowest Enrollment centres Name of the Centre Enrollment Pass % Navelim 1522 94.28 (Highest) Paingin 230 96.96 (Lowest) 3 List of Schools with Cent Percent Results School Name Appeard Passed NI percentage 01.02-ST. -

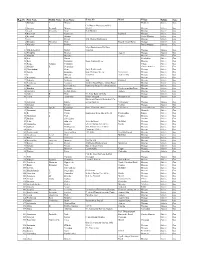

Reg No First Name Middle Name Last Name House No Ward Village

Reg_No First Name Middle Name Last Name House No Ward Village Taluka State 1 Damodar Y Mauzo Majorda Salcete Goa C/o Mauzo Photo Studio/Old 2 Naraina Ramnath Mauzo Market Margao Salcete Goa 3 Anant Narcinva Naik New Market Margao Salcete Goa 4 Bhanudas Kossambe Pajifond Margao Salcete Goa 6 Bernand F. D'souza Gogol Margao Salcete Goa 7 Apa Kamat 294 , Behind Rashtramat Margao Salcete Goa 8 Damodar Narcinva Naik Rua de Abade Faria Margao Salcete Goa 9 Manohar S. Prabhu Borda Margao Salcete Goa Maya Book Stores,Vit-Rose 11 Mahabaleshwar Borkar Mansion Margao Salcete Goa 12 Peregrino D'costa Aquem Margao Salcete Goa 13 Noordin Mavany Margao Salcete Goa 15 Irene Barros Betalbatim Salcete Goa 16 Bala Kakodkar Sagar Printing Press Margao Salcete Goa 19 Roque Santana Fernandes Velim Salcete Goa 21 Madhav P. Neurenkar Comba margao Salcete Goa 23 Chandrakant Keni Daily Rashtramath Margao Salcete Goa 26 Suresh Kakodkar Opp.Chitrapur Garage Vidyanagar Margao Salcete Goa 27 C. P. D'Costa Villa Emi Aquem Alto Margao Salcete Goa 28 Anastacio Almeida Margao Salcete Goa 29 Prakash S. Nadkarni 104 Pajifond Margao Salcete Goa 30 Pandurang Sambari Sambari Book House Station Road Margao Salcete Goa 31 Hari Pai Fondekar Ratnadeep Bldg. Nr railway station Margao Salcete Goa 32 Diwakar Kakodkar Varde valaulikar Road Margao Salcete Goa 34 Shrinivas U. Kakule Bhobe Aquem Margao Salcete Goa 36 Satyen K. Naik Nr. State Bank Of India Margao Salcete Goa 40 Anant S. Assoldekar Brito Compund Metropole rd Margao Salcete Goa Block no5,Bank Of India Staff Co- 42 Satyawan Kunde op hsg. -

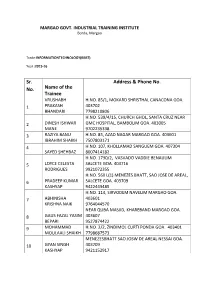

Sr. No. Name of the Trainee Address & Phone

MARGAO GOVT. INDUSTRIAL TRAINING INSTITUTE Borda, Margao Trade:INFORMATIONTECHNOLOGY(BBBT) Year :2015-16 Sr. Address & Phone No. No. Name of the Trainee VRUSHABH H.NO. 85/1, MOKARD SHRISTHAL CANACONA GOA. 1 PRAKASH 403702 BHANDARI 7798210806 H.NO. 539/4/15, CHURCH GHOL, SANTA CRUZ NEAR 2 DINESH ISHWAR GMC HOSPITAL, BAMBOLIM GOA. 403005 MANE 9702235338 3 RAZIYA BANU H.NO. 85, AZAD NAGAR MARGAO GOA. 403601 IBRAHIM SHAIKH 7507803171 4 H.NO. 107, KHOLLAMAD SANGUEM GOA. 407304 SAYED SHEHBAZ 8007414182 H.NO. 1730/2, VASVADO VADDIE BENAULIM 5 LOYCE CELESTA SALCETE GOA. 403716 RODRIGUES 9921072355 H.NO. 560 L(1) MENEZES BHATT, SAO JOSE DE AREAL, 6 PRADEEP KUMAR SALCETE GOA. 403709 KASHYAP 9422443485 H.NO. 114, SIRVODEM NAVELIM MARGAO GOA. 7 ABHINISHA 403601 KRISHNA NAIK 9764044570 NEAR QUBA MASJID, KHAREBAND MARGAO GOA. 8 GAUS FAZAL YASIM 403607 BEPARI 9527874422 9 MOHAMMAD H.NO. 2/2, ZINDIMOL CURTI PONDA GOA. 403401 MOULAALI SHAIKH 7798687573 MENEZESBHATT SAO JOSW DE AREAL NESSAI GOA. 10 GYAN SINGH 403709 KASHYAP 9421152917 PRAJAKTA H.NO. 489, BORDA POST OFFICE FATORDA MARGAO 11 GURUDAS GOA. 403602 VERNEKAR 8411946366 H.NO. 973, BAIDA CHINCHINIM SALCETE GOA. 12 403715 MELVIN REBELLO 9673633809 H.NO. 98, GOURI RADIO HOUSING BOARD MARGAO - 13 TUSHAR VINAYAK GOA. 403601 GAWDE 8407976233 H.NO. 35, NUVEM DONGORIM, MAJORDA SALCETE 14 SEMONI ROESINA GOA. ALPHONSO 9096300158 15 NOFA GLANCE H.NO. 932/8, MODDI NAVELIM SALCETE GOA. FERNANDES 9011252411 H.NO. 988, ASSOLNA AMBELIM, ADDIR SALCETE GOA. 16 SANFORD 403701 OLIVERIA 9673240668 H.NO. 149, COLLEM BAZARWADA BHARBANDODA. 17 PRADYNA 403410 TALAULIKER 9730332344 H.NO. -

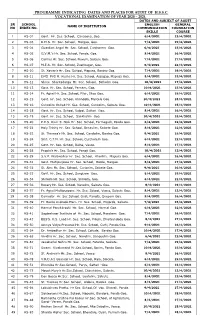

Programme Indicating Dates and Places for Audit of Hssc Vocational

PROGRAMME INDICATING DATES AND PLACES FOR AUDIT OF H.S.S.C. VOCATIONAL EXAMINATION OF YEAR 2020 – 2021. DATES AND SUBJECT OF AUDIT SR SCHOOL ENGLISH GENERAL NAME OF INSTITUTION NO INDEX NO. COMMUNICATION FOUNDATION SKILLS COURSE 1 HS-01 Govt. Hr. Sec. School, Canacona, Goa. 6/4/2021 12/4/2021 2 HS-03 R.M.S. Hr. Sec. School, Margao, Goa. 7/4/2021 19/4/2021 3 HS-04 Guardian Angel Hr. Sec. School, Curchorem Goa. 6/4/2021 15/4/2021 4 HS-05 G.V.M.’s Hr. Sec. School, Ponda, Goa. 8/4/2021 16/4/2021 5 HS-06 Carmel Hr. Sec. School, Nuvem, Salcete Goa. 7/4/2021 17/4/2021 6 HS-07 M.E.S. Hr. Sec. School, Zuarinagar, Goa. 6/4/2021 12/4/2021 7 HS-10 St. Xavier’s Hr. Sec. School, Mapusa, Bardez Goa. 7/4/2021 19/4/2021 8 HS-11 DMS PVS M. Kushe Hr. Sec. School, Assagao, Mapusa Goa. 8/4/2021 15/4/2021 9 HS-12 Shree Shantadurga Hr. Sec. School, Bicholim Goa. 10/4/2021 17/4/2021 10 HS-13 Govt. Hr. Sec. School, Pernem, Goa. 10/4/2021 15/4/2021 11 HS-14 Fr. Agnel Hr. Sec. School, Pilar, Ilhas Goa. 6/4/2021 15/4/2021 12 HS-15 Govt. Hr. Sec. School, Khandola, Marcela Goa. 10/4/2021 15/4/2021 13 HS-16 Cuncolim United Hr. Sec. School, Cuncolim, Salcete Goa. 10/4/2021 15/4/2021 14 HS-18 Govt. Hr. Sec. -

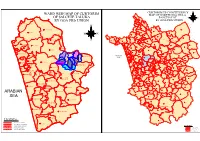

WARD WISE MAP of CURTORIM of SALCETE TALUKA by GOA Pris UNION

CURTORIM ZP CONSTITUENCY N WARD WISE MAP OF CURTORIM MAP OF SOUTH GOA ZILLA OF SALCETE TALUKA CANDOLA PANCHAYAT W E ORGAO BY GOA PRIs UNION BETQUI BY GOA PRIs UNION TIVREM VOLVAI S NAGOA ADCOLNA K N BOMA SAVOI-VEREM A CUNCOLIM R GANGEM QUERIM VAGURBEM CUNDAIM LOUTULIM SURLA N USGAO VERNA PRIOL AGLOTE A W E VELINGA CANDEPAR MARCAIM CURTI T PILIEM BANDORA MOLEM A MORMUGAO PONDA SANCORDEM CHICALIM DARBANDORA S QUELOSSIM P O N D A CODAR CAMURLIM QUELA K DURBHAT BETORA M O R M U G A OSANCOALE TALAULIM ISSORCIM D A R B A N D O R A A UTORDA VADI S PALE MAJORDA CHICOLNA NIRANCAL CUELIM NAGOA BORIM CARANZOL NUVEM SANGOD VELSAO Xref CODLI T LOUTULIM COLLEM CANSAULIM CONXEM CALATA VERNA RACHOL CODLI A AROSSIM GONSUA RAIA SIGAO SHIRODA CAMURLIM T UTORDA C0RMONEM MAJORDA NUVEM CAMORCONDA SONAULI BETALBATIM CALATA RACHOL GONSUA RAIA E WARD NO. VI BANDOLI WARD NO. VIII WARD NO. IX MOISSAL DUNCOLIM BETALBATIM CALEM MACASANA ARABIAN DUNCOLIM BOMA MACASANA SANTONA WARD NO. VII WARD NO. X GAUNDAULIM CURTORIM RUMBEREM SEA PANCHAVADI WARD NO. V SERAULIM OXEL GAUNDAULIM MARGAO CURTORIM COLVA ANTOREM VANELIM GUIRDOLIM WARD NO. I WARD NO. XI SANVORDEM DUDAL CANA DAVORLIM XELVONA DONGURLI SERAULIM SERNABATIM WARD NO. IV ODAR MARGAO ADULSIM CURCHOREM CORANGINIM XIC-XELVONA MAULINGUEM COLVA AQUEM DICARPALE CAVORIM COMPROI BENAULIM ASSOLDA WARD NO. II S A L C E T E COSTI K PATIEM SAO JOSE VANELIM GUIRDOLIM DE AREAL COTOMBI MUGULI DRAMAPUR A XELDEM AVEDEM TALAULIM CANA CHAIFI DAVORLIM VARCA CACORA R MULEM UGUEM SIRLIM AMONA SANGUEM TUDOU SERNABATIM WARD NO. -

Official Gazette Government of Goa, Daman and Diu

I REGD. GOA-S 1 Panaji, 10th July, 1980 (Asadha 19, 1902) SERIES III No. 15 OFFICIAL GAZETTE GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN AND DIU GOVERNMENT OF GOA, DAMAN AND DIU Works, Education and Tourism Department Public Works Department . Works Division I (Bldgs. & Com.) North - Panaji Tender Notice No. B/Adm-8/16/8().81 The Executive Engineer, Works Division I (Bldgs. & Com.) North, Panaji invites on behalf of the President of Iz.1dia Perce~tage Rate Tenders from approved and eligible con tracto,rs upto 3.00 p. m. on 15th July. 1980 for the work of: - Estimated Earnest Time limit Class of Cost of Sr. No DescrIptions amount money in days contractors tenders ______________________~, ____________________Rs~. ________Rs~. __~ ______~ __________ Rs. 1. Demolition of structures on the western side O'f Rua de Ourem............................................................ 13,123-92 329/- 45 days V & above. 20/- incl. Monsoon. 2. Making of partitions in the newly opened Wireless Station at POlice Head Quarters Panaji..................... 1,387-50 35/- 30 days V & above. 10/- incl. Monsoon. 3. Provision of pumping Installation for Directorate of Education Bldg. at Panaji. ................................... 10,000-00 250/- 45 days V & above. 10/- incl. Monsoon. ~ Tenders will be opened at 3.30 p. m. on the same day. Contractor must produce Income - Tax Clearance Certificate Conditions . and tender forms can be had from the above before issuing the tenders. office upto 12.00 a. In. on July 14th 1980, during working hours. Tenders of contractors who do not deposit earnest. Panaji, 1st July. 19~O. - The Executive Engineer, 8. Y. money in the prescribed fOrm. -

Circular No. 33

GOA BOARD OF SECONDARY AND HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION (A Corporate Statutory Body constituted by an Act of the State Legislature ) (POSTED UNDER CERTIFICATE OF POSTING) MOST URGENT SPECIAL ATTENTION PLEASE Circular No: 33 GBSHSE/I.T./Brd-Ele-2017/ Date: 21/09/2018 To, The Heads of all recognized Higher Secondary Institutions Under the jurisdiction of this Board(South Goa District only) Sub: Preparation of List of Voters for Election for the vacancy caused by resignation of one of the Board member Sir/Madam, This is with reference to vacancy caused by resignation of one Class B (iii) member, Dr. Uday Chepo Gaonkar , for the tenure 2017 – 2021. In pursuance of the provisions of section 12 , 13 and 18 of the Goa Secondary & Higher Secondary Board (Amendments) Act 1996 (to the Principal Act 1975) the election of a member of the Board under section 12(1) Class B (iii) of the said act for the tenure 2017 – 2021 is proposed to be held during last week of October. The procedure of the election will be as laid down by Goa, Daman, Diu Secondary & Higher Secondary Education Board Members Election Procedure Rules, 1979 published in the Official Gazette No.47 series I dated 21/02/1980. In view of the conduct of said election this Board has to prepare list of voters Principals of Higher Secondary Institution. In order to enable this office to take up this work, you are hereby requested to kindly extend your co-operation by way of complying the following. Action Please supply the information about the Principal of your Institution as on 12th October 2018 in the proforma enclosed herewith (Appendix - A) While taking action, the following may be carefully noted. -

Transoceanic Creolization and the Mando of Goa*

Modern Asian Studies , () pp. –. © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX First published online January Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana: Transoceanic creolization and the mando of Goa* ANANYA JAHANARA KABIR Department of English, King’s College London Email: [email protected] Abstract The mando is a secular song-and-dance genre of Goa whose archival attestations began in the s.Itisstilldancedtoday,instagedratherthansocialsettings.Itslyricsarein Konkani, their musical accompaniment combine European and local instruments, and its dancing follows the principles of the nineteenth-century European group dances known as quadrilles, which proliferated in extra-European settings to yield various creolized forms. Using theories of creolization, archival and field research in Goa, and an understanding of quadrille dancing as a social and memorial act, this article presents the mando as a peninsular, Indic, creolized quadrille. It thus offers the first systematic examination of the mando as a nineteenth-century social dance created through * This article is based on fieldwork in Goa (field visits made in September , December , June ), as well as multiple field visits to Cape Verde, Brazil, Mozambique, Angola, and Lisbon (–), which have enabled me to comprehend music and dance across the Portuguese-speaking world. I have also drawn on fieldwork on the quadrille in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius, Seychelles, and Réunion, October– November ). All research fieldwork (except that in Angola) was done through ERC Advanced Grant funding. -

Proposal for Curtorim BHS 2016

Proposal for Curtorim BHS 2016 PROPOSAL FOR BIODIVERSITY HERITAGE SITE Extent of BHS proposed – Ralloi Tollem – (Vaingnoddi Add ) – Angdi Tollem (opp. Curtorim Church) – (Sirge Add – Chowk – dyke) – Kottambo Poi ( water channel upto river Zuari) Along with Sonbem (Maina) Tollem , Mai Tollem, Kum (Colomba) Tollem and Gud Tollem ( 6 lakes) Along with associated Khazan Areas, Mangroves, Agroecosystems and springs. Fig: Indicative Google Image CURTORIM BIODIVERSITY HERITAGE SITE (RAITOLLEM –ZUARI: INTEGRATED TRADITIONAL AGRO- PISCI- ECOSYSTEM). PREPARED FOR BMC CURTORIM Assisted by CHOWGULE COLLEGE as technical support group FEBRUARY - 2018 Page 1 of 84 Proposal for Curtorim BHS 2016 (Imp. Note: This document contains matter which will constitute final BHS document. However index, layout etc. will be ensured after inclusion of all the inputs and before printing final copy) SECTION I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction: Curtorim- Over view The village of Curtorim – Codtary, Coddetary, or Kardeley as it seems the village was known in olden times the village was baptized by the Portuguese as Curtorim. It was also known Cuddtari (Aldeia de Curtorim, pg.5, Diario de Goa, supplemento 1-2-1956 por Agusto Rodrigues, son of Curtorim, Kuddutare Grama (in an inscription of 1546, Bharatha Kaumadi, pg.449 by prof. Dr. George Moraes), Kuddasthali, (sthali- place), (Boletim do institute de Vasco de Gama, No.69- 1952, pg. 26 by prof.P. Pissurlencar), Kurhtori, (Dr. Jose Pereira- son of Curtorim in Marg). It is now known as Curtorim, (English, Portuguese), Curtore (konkani), Kuddtore (Hindi, and Marathi), and probably Kuddtorihalli, (halli- village) in Kannada. 1.2 Location: The village of Curtorim is located 8 kms away from Margao, the main town of Salcete. -

THE GOAN DIASPORA: a Study of Socio-Cultural Dynamics in Goa

THE GOAN DIASPORA: A Study of Socio-cultural Dynamics in Goa By Sachin Savio Moraes Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology Department of Sociology Goa University GOA December 2015 ii DECLARATION I, Sachin Savio Moraes, hereby declare that this thesis entitled ‘The Goan Diaspora: A Study of Socio-cultural Dynamics in Goa’ is the outcome of my own study undertaken under the guidance of Dr. Ganesha Somayaji, Professor and Head, Department of Sociology, Goa University, Goa. It has not previously fromed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other university. I have duly acknowledged all the sources used by me in the preparation of this thesis. Place: Goa University Date: Sachin Savio Moraes iii CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘The Goan Diaspora: A Study of Socio-cultural Dynamics in Goa’ is the record of the original work done by Shri Sachin Savio Moraes under my guidance. The results of the research presented in this thesis have not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other university. Place: Goa University Dr. Ganesha Somayaji Professor and Head Department of Sociology Goa University, Goa Date: iv CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgement vi-xi List of Figures xii List of Tables xiii-xiv List of Photos and Maps xv 1. Introduction 1-32 2. Theoretical Perspectives and Conceptual framework 33-49 3. The Making of International Migration in AVC-GOA: A Historical Perspective 50-86 4.