THE GOAN DIASPORA: a Study of Socio-Cultural Dynamics in Goa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

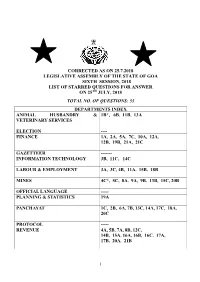

Corrected As on 25.7.2018 Legislative Assembly of the State of Goa Sixth Session, 2018 List of Starred Questions for Answer on 25Th July, 2018

CORRECTED AS ON 25.7.2018 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF GOA SIXTH SESSION, 2018 LIST OF STARRED QUESTIONS FOR ANSWER ON 25TH JULY, 2018 TOTAL NO. OF QUESTIONS: 55 DEPARTMENTS INDEX ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & 1B*, 6B, 11B, 13A VETERINARY SERVICES ELECTION ---- FINANCE 1A, 2A, 5A, 7C, 10A, 12A, 12B, 19B, 21A, 21C GAZETTEER ------- INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 3B, 11C, 14C LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 3A, 3C, 4B, 11A, 15B, 18B MINES 4C*, 5C, 8A, 9A, 9B, 13B, 15C, 20B OFFICIAL LANGUAGE ----- PLANNING & STATISTICS 19A PANCHAYAT 1C, 2B, 6A, 7B, 13C, 14A, 17C, 18A, 20C PROTOCOL ----- REVENUE 4A, 5B, 7A, 8B, 12C, 14B, 15A, 16A, 16B, 16C, 17A, 17B, 20A, 21B 1 SL. MEMBER QUESTION DEPARTMENT NO. NOS 1A FINANCE 1. SHRI WILFRED D’SA 1B* ANIMAL HUSBANDRY & VETERINARY SERVICES 1C PANCHAYAT 2. SHRI FILIP NERI 2A FINANCE RODRIGUES 2B PANCHAYATI RAJ 3A LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 3. SHRI SUBHASH 3B I.T. SHIRODKAR 3C LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 4A REVENUE 4. SHRI PRASAD GAONKAR 4B LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 4C* MINES 5A FINANCE 5. SHRI LUIZINHO FALEIRO 5B REVENUE 5C MINES & GEOLOGY 6A PANCHAYATI RAJ 6. SHRI CHURCHILL ALEMAO 6B ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 7A REVENUE SHRI ALEIXO REGINALDO 7B PANCHAYAT 7. LOURENCO 7C FINANCE 8A MINES & GEOLOGY 8B REVENUE 8. SHRI CHANDRAKANT KAVALEKAR 9A MINES & GEOLOGY 9B MINES & GEOLOGY 9. SHRI DEEPAK PAUSKAR 10. SHRI GLENN SOUZA TICLO 10A FINANCE 11A LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 11. SHRI ANTONIO FERNANDES 11B ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 11C INFORMATION & TECHNOLOGY 2 12. SHRI NILESH CABRAL 12A FINANCE 12B FINANCE 12C REVENUE SHRI RAJESH PATNEKAR 13A ANIMAL HUSBANDRY 13 13B MINES 13C PANCHAYAT 14A PANCHAYAT 14 SHRI DAYANAND SOPTE 14B REVENUE 14C INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY 15A REVENUE 15 SHRI RAVI NAIK 15B LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 15C MINES 16A REVENUE SHRI JOSE LUIS CARLOS 16B REVENUE 16 ALMEDA 16C REVENUE 17A REVENUE 17B REVENUE 17 SHRI FRANCISCO SILVEIRA 17C PANCHAYATI RAJ SHRI NILKANTH 18A PANCHAYATI RAJ 18 HALARNKAR 18B LABOUR & EMPLOYMENT 19A PLANNING & STATISTIC SHRI PRATAPSINGH RANE 19 19B FINANCE 20A REVENUE 20B MINES & GEOLOGY 20 SHRI ISIDORE FERNANDES 20C PANCHAYATI RAJ 21A FINANCE 21B REVENUE 21. -

Carrying Capacity of Beaches of for Providing Shacks & Other Temporary Goa Seasonal Structures in Private Areas

Carrying Capacity of Beaches of for Providing Shacks & Other Temporary Goa Seasonal Structures in Private Areas Submitted to Government of Goa Prepared by NATIONAL CENTRE FOR SUSTAINABLE COASTAL MANAGEMENT Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change Government of India Carrying Capacity of Beaches of Goa for Providing Shacks & Other Temporary Seasonal Structures in Private Areas Foreword India is forging ahead with a high development agenda, especially along the long coastline, which inadvertently causes adverse impacts on the environment. Most of these activities are unplanned, leading to an imbalance in ecological sustainability. It is evident that developmental activities need to be regulated and managed, so that deterioration of the environment can either be minimized or avoided. This can be achieved by estimating the carrying capacity of a system that enables better planning for development, concurrently safeguarding ecological and environmental and social concerns. The State of Goa is one of world‟s most renowned tourism destinations with several natural beaches along its 105 km coastline, with a tourist footfall of over 50,00,000 tourists per year. Despite such heavy human pressure on a limited coastal scape, the Government of Goa has attempted to maintain the integrity of its beaches by regulation and management measures. However, a more systematic and scientific approach, was necessary to protect the ecological and environmental resources and to ensure livelihood sustainability. Based on such principles, the present study on carrying capacity of beaches and the adjacent private areas was undertaken by National Centre for Sustainable Coastal Management, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Carrying capacity was determined using several international and national best practices to determine the scenarios and indicators for the assessment. -

O. G. Series III No. 30.Pmd

Reg. No. G-2/RNP/GOA/32/2018-20 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 25th October, 2018 (Kartika 3, 1940) SERIES III No. 30 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY Note:- There is one Supplement to the Official Gazette, Consequently, the Certificate of Registration Series III No. 29 dated 19-10-2018 namely, No. WATS000307 issued under the said Act stands Supplement dated 23-10-2018 from pages 1167 to cancelled. 1178 regarding Notification from Department of Finance [Directorate of Small Savings & Lotteries Margao, 9th October, 2018.— The Dy. Director of (Goa State Lotteries)]. Tourism & Prescribed Authority (South), Rajesh A. Kale. GOVERNMENT OF GOA ________ Department of Tourism Order ___ No. 5/S(1-842)2018-DT/254 Order By virtue of the powers conferred upon me under Section 10(1)(a) of the Goa Registration of Tourist No. 4/S(2-239)2018-DT/252 Trade Act, 1982, I, Shri Rajesh A. Kale, Prescribed By virtue of the powers conferred upon me under Authority (South), hereby remove the name of Section 19 of the Goa Registration of Tourist Trade Socorro Guest House, c/o Shri Socorro Barretto, Act, 1982, I, Shri Rajesh A. Kale, Dy. Director & H. No. 587/A, Pulvaddo, Benaulim, Salcete, South Prescribed Authority, hereby remove the name Goa 403 716, as Shri Socorro Barretto (Proprietor) of Shri Noby F. Baretto, r/o H. No. 354/2/A, has ceased to operate the said Guest House in his Khandivaddo, Cavelossim, Salcete-Goa for his premises. Banana Ride Activity on Boat bearing No. GOA- Consequently, the Certificate of Registration -199-WS, as the said activity has been bearing No. -

Marine Litter in the South Asian Seas (Sas) Region

MARINE LITTER IN THE SOUTH ASIAN SEAS (SAS) REGION DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL ACTION PLAN ON MARINE LITTER INDIA – COUNTRY REPORT Contributors: Dr. M. V. Ramanamurthy Director & Scientist-G, National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR) Dr. Pravakar Mishra National Focal Point Scientist-F, National Centre for Coastal Research (NCCR) Dr. P. Vethamony National Consultant Former Chief Scientist &AcSIR Professor, CSIR-NIO, Goa, India May 2018 1 Content Page No. Foreword 6 Executive summary 7 Key messages 1. Introduction and background 9 2. Marine litter status at national level 15 2.1 Origin, typology, pathways and trends 15 2.2 Classification of marine litter 17 2.3 Quantification 18 2.4 Sources (through rivers and canals, dumping by ships and boats, 36 surface drainage etc.) 3. Circulation of marine litter 39 3.1 Marine litter circulation 39 3.2 Sources from land based sectors 41 3.3 Sources Sea based sectors 46 3.4 National, sub-national and local institutions responsible for solid waste 47 management 4. National impact of marine litter 48 4.1 Social 48 4.2 Economic 53 4.3 Ecological/Environment 59 5. Management agencies, policies, strategies and activities taken to minimize 66 the marine litter 5.1 Management agencies and their responsibilities 66 5.2 Management policies and strategies and their effectiveness 66 5.3 Management activities for combating land, beach and and marine 68 based litter 6. National marine litter monitoring programme 70 6.1 Monitoring 70 6.2 Baseline and targets in the context of monitoring marine litter in the sea 71 7. Knowledge gaps, research and analysis for setting priorities 72 8. -

JETIR Research Journal

© 2018 JETIR December 2018, Volume 5, Issue 12 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Learning from the Past: Study on Sustainable Features from Vernacular Architecture in Coastal Karnataka. 1Vikas.S.P, 2Sagar.V.G, 3Manoj Kumar.G, 4Neeraja Jayan 1Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 2Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 3Student, 6th sem, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY, 4Associate Professor, School of Architecture, REVA UNIVERSITY. Abstract: Vernacular architecture can be defined as that architecture characterized based on the function, construction materials and traditional knowledge specific and unique to its location. It is indigenous to a specific time and place and also incorporates the skills and expertise of local builders. The paper is elaborated on the basis of case studies of settlements in the Coastal region of Karnataka with special reference to Barkur and Brahmavar of Udupi regions. It has evolved over generations with the available building materials, climatic conditions and local craftsmanship. However, some examples of vernacular architecture are still found in Barkur and Brahmavar. These vernacular residential dwellings provided with various passive solar techniques including natural cooling systems and are more comfortable compared to the contemporary buildings in today's context. This research paper into various parameters which defines the vernacular architecture of coastal Karnataka and how these parameters can be interpreted in today’s context so that it can be used effectively in the future residential designs. keywords - sustainable, vernacular architecture, modern building, sustainability. I. INTRODUCTION Udupi is a city in the southwest Indian state of Karnataka and is known for its Hindu temples, including the 13th century Krishna temple which houses the statue of lord Krishna. -

Call Letter for the Post of Sweeper

BY REGISTERED A/D HIGH COURT OF BOMBAY AT GOA, PANAJI REF. ADVERTISMENT NO. 1/2016 No. HCB/GOA/A-1/Sweeper/2017/ Date : 04.10.2017 Latest Passport size Photograph of Entry No. : the candidate CALL LETTER With reference to your application for the post of Sweeper, you are required to appear for the Practical Test/Physical Fitness test/Viva-voce at the High Court of Bombay at Goa, Panaji, on 11.10.2017 from 11:00 a.m. onwards. The Practical test will be of 30 marks, Physical fitness (10 marks) and Viva Voce (10 marks). If you fail in Practical test you will not be considered for Physical fitness and for viva-voce for the post of Sweeper. Please note that you will have to appear for the Practical test/Physical fitness and Viva-voce at your own cost. You are required to bring this call letter with you on the day of Practical test/Physical fitness/Viva Voce along with all your testimonials in original. If you fail to bring this Call letter with you on the day of Practical test/Physical fitness/Viva Voce, perhaps you will not be allowed to appear for the same on 11.10.2017 as the case may be and no further opportunity shall be given. Any attempt on your part to influence or pressurise the members of the Selection Committee shall render you debarred from the selection process. (S. C. Chandak) Registrar (Adm.) To, Sr. Entry Name/Address of the candidates No. No. 1 25 VIKAS TULSHIDAS NAIK H. -

Sustainable Rammed Earth Structure: a Structurally Integral, Cost-Effective and Eco- Friendly Alternative to Conventional Construction Material

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8, Issue-11S, September 2019 Sustainable Rammed Earth Structure: A Structurally Integral, Cost-Effective And Eco- Friendly Alternative to Conventional Construction Material Pavan Totla, Maurya Sadwilkar, Samidha More, Blessy Kallada, Bhalchandra Deshmukh, Akshata Puranik Abstract: While constructing (developing) any structure mineral soil and other resources required are also available at a (asset), its impact on the environment should always be assessed. comparatively low cost. A structure (say home wall) can be built As we know, cement is a key building material that is commonly using Rammed Earth in approximately 1/5thcost than that used but also creates pollution during its manufacturing, storage required for Stone wall. So, Rammed Earth based construction handling, transportation and usage. So, what-if this building projects can be linked to Government’s Low-Cost Housing material can be significantly replaced by some other building schemes like Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY, PMGAY). material that is far eco-friendlier. Mother Nature i.e. our planet For building Rammed Earth Structures, unskilled labors can be Earth offers us naturally existing and abundant Soil (mud) that easily trained and hence creates a good opportunity to employ can be used as an alternative building material. Cement, as a unemployed people including locals. In this way this project can main component of construction material mix, when replaced by tangibly contribute to bring about a socioeconomic shift/change. naturally and locally available mineral soil (in different proportions) will result in reduced carbon footprints which Keywords: Cost Efficiency, Mineral Soil, Socioeconomic, otherwise is high for cement supply chain. -

Expectant Urbanism Time, Space and Rhythm in A

EXPECTANT URBANISM TIME, SPACE AND RHYTHM IN A SMALLER SOUTH INDIAN CITY by Ian M. Cook Submitted to Central European University Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Supervisors: Professor Daniel Monterescu CEU eTD Collection Professor Vlad Naumescu Budapest, Hungary 2015 Statement I hereby state that the thesis contains no material accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. The thesis contains no materials previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgment is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Budapest, November, 2015 CEU eTD Collection Abstract Even more intense than India's ongoing urbanisation is the expectancy surrounding it. Freed from exploitative colonial rule and failed 'socialist' development, it is loudly proclaimed that India is having an 'urban awakening' that coincides with its 'unbound' and 'shining' 'arrival to the global stage'. This expectancy is keenly felt in Mangaluru (formerly Mangalore) – a city of around half a million people in coastal south Karnataka – a city framed as small, but with metropolitan ambitions. This dissertation analyses how Mangaluru's culture of expectancy structures and destructures everyday urban life. Starting from a movement and experience based understanding of the urban, and drawing on 18 months ethnographic research amongst housing brokers, moving street vendors and auto rickshaw drivers, the dissertation interrogates the interplay between the city's regularities and irregularities through the analytical lens of rhythm. Expectancy not only engenders violent land grabs, slum clearances and the creation of exclusive residential enclaves, but also myriad individual and collective aspirations in, with, and through the city – future wants for which people engage in often hard routinised labour in the present. -

Goa & Mumbai 6

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Panaji & Central Goa Why Go? Panaji ..............................111 However much you do like to be beside the seaside, the West of Panaji ................124 attractions of central Goa are as quintessentially Goan as a Old Goa ......................... 126 dip in the Arabian Sea. What hedonism is to the north and Divar Island ...................133 relaxation is to the south, culture, scenery and history are to this central portion of the state, eased in between the Man- Goa Velha ......................134 dovi and Zuari Rivers. Talaulim .........................135 Panaji (or Panjim, its former Portuguese name, by which Pilar ...............................135 it’s still commonly known) is Goa’s lazy-paced state capital, Ponda ............................135 perfect for a stroll in the Latin Quarter, while just down the Bondla Wildlife road is Old Goa, the 17th century’s ‘Rome of the East’. Sanctuary ..................... 140 Top this off with visits to temples and spice plantations Molem & Around ........... 141 around Ponda, two of Goa’s most beautiful wildlife sanctu- Tambdi Surla .................142 aries, time-untouched inland islands, and India’s second- Hampi ............................143 highest waterfall, and it would be possible to spend a week Around Hampi ...............148 here without making it to a single beach. Hospet ...........................149 When to Go Best Places to Eat Central Goa is less about beaches than the south and north » Upper House, Panaji (p 120 ) of the state, making it less dependent on the high season. October and April are both good, cool, lower-priced times » Sher-E-Punjab, of year to visit Panaji and its surroundings, particularly if Panaji (p 120 ) you’re planning on a lot of sight-seeing; October, moreo- » Vihar Restaurant, ver, is the best time for wildlife-watching in the region’s Panaji (p 121 ) reserves. -

The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada's Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities

Brown Baby Jesus: The Religious Lifeworlds of Canada’s Goan and Anglo-Indian Communities Kathryn Carrière Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the PhD degree in Religion and Classics Religion and Classics Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Kathryn Carrière, Ottawa, Canada, 2011 I dedicate this thesis to my husband Reg and our son Gabriel who, of all souls on this Earth, are most dear to me. And, thank you to my Mum and Dad, for teaching me that faith and love come first and foremost. Abstract Employing the concepts of lifeworld (Lebenswelt) and system as primarily discussed by Edmund Husserl and Jürgen Habermas, this dissertation argues that the lifeworlds of Anglo- Indian and Goan Catholics in the Greater Toronto Area have permitted members of these communities to relatively easily understand, interact with and manoeuvre through Canada’s democratic, individualistic and market-driven system. Suggesting that the Catholic faith serves as a multi-dimensional primary lens for Canadian Goan and Anglo-Indians, this sociological ethnography explores how religion has and continues affect their identity as diasporic post- colonial communities. Modifying key elements of traditional Indian culture to reflect their Catholic beliefs, these migrants consider their faith to be the very backdrop upon which their life experiences render meaningful. Through systematic qualitative case studies, I uncover how these individuals have successfully maintained a sense of security and ethnic pride amidst the myriad cultures and religions found in Canada’s multicultural society. Oscillating between the fuzzy boundaries of the Indian traditional and North American liberal worlds, Anglo-Indians and Goans attribute their achievements to their open-minded Westernized upbringing, their traditional Indian roots and their Catholic-centred principles effectively making them, in their opinions, admirable models of accommodation to Canada’s system. -

The Case of Goa, India

109 ■ Article ■ The Formation of Local Public Spheres in a Multilingual Society: The Case of Goa, India ● Kyoko Matsukawa 1. Introduction It was Jurgen Habermas, in his Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere [1991(1989)], who drew our attention to the relationship between the media and the public sphere. Habermas argued that the public sphere originated from the rational- critical discourse among the reading public of newspapers in the eighteenth century. He further claimed that the expansion of powerful mass media in the nineteenth cen- tury transformed citizens into passive consumers of manipulated public opinions and this situation continues today [Calhoun 1993; Hanada 1996]. Habermas's description of historical changes in the public sphere summarized above is based on his analysis of Europe and seems to come from an assumption that the mass media developed linearly into the present form. However, when this propo- sition is applied to a multicultural and multilingual society like India, diverse forms of media and their distribution among people should be taken into consideration. In other words, the media assumed their own course of historical evolution not only at the national level, but also at the local level. This perspective of focusing on the "lo- cal" should be introduced to the analysis of the public sphere (or rather "public spheres") in India. In doing so, the question of the power of language and its relation to culture comes to the fore. 松 川 恭 子Kyoko Matsukawa, Faculty of Sociology, Nara University. Subject: Cultural Anthropology. Articles: "Konkani and 'Goan Identity' in Post-colonial Goa, India", in Journal of the Japa- nese Association for South Asian Studies 14 (2002), pp.121-144. -

South-Goa-Map-Of-Ideal-Villages

SOUTH GOA MAP OF N DISTRICT DEVELOPMENT N IDEAL VILLAGES MAP OF SOUTH GOA CANDOLA BY GOA PRIs UNION W E CANDOLA BY GOA PRIs UNION W E ORGAO ORGAO BETQUI CURTORIM BETQUI CURTORIM TIVREM TIVREM VOLVAI S 2 VOLVAI S ADCOLNA K ADCOLNA K BOMA SAVOI-VEREM A BOMA SAVOI-VEREM A CUNCOLIM CUNCOLIM R R GANGEM GANGEM QUERIM VAGURBEM QUERIM VAGURBEM CUNDAIM CUNDAIM SURLA 1 SURLA N 4 N USGAO USGAO PRIOL PRIOL VELINGA CANDEPAR AGLOTE A VELINGA CANDEPAR AGLOTE A MARCAIM MARCAIM 3 CURTI T CURTI T PILIEM PILIEM BANDORA BANDORA MOLEM A PONDA MUNICIPALITY MOLEM A MORMUGAO PONDA SANCORDEM MORMUGAO MUNICIPALITY 5 SANCORDEM CHICALIM DARBANDORA DARBANDORA CHICALIM 24 QUELOSSIM QUELOSSIM P O N D A CODAR K P O N D A CODAR K DURBHAT QUELA 25 DURBHAT QUELA BETORA BETORA M O R M U G A OSANCOALE TALAULIM M O R M U G A OSANCOALE TALAULIM ISSORCIM D A R B A N D O R A A ISSORCIM D A R B A N D O R A A VADI VADI 6 18 S S PALE PALE CHICOLNA NIRANCAL CHICOLNA NIRANCAL CUELIM NAGOA BORIM CUELIM NAGOA BORIM CARANZOL CARANZOL SANGOD SANGOD VELSAO Xref CODLI T VELSAO Xref CODLI T LOUTULIM COLLEM LOUTULIM COLLEM CANSAULIM CONXEM CANSAULIM CONXEM VERNA VERNA CODLI A A 8 CODLI AROSSIM AROSSIM SIGAO 9 SIGAO SHIRODA SHIRODA CAMURLIM T CAMURLIM T UTORDA C0RMONEM UTORDA C0RMONEM MAJORDA CAMORCONDA MAJORDA 7 CAMORCONDA NUVEM SONAULI NUVEM SONAULI CALATA RACHOL CALATA RACHOL GONSUA E GONSUA E RAIA BANDOLI 10 RAIA BANDOLI MOISSAL MOISSAL BETALBATIM CALEM BETALBATIM 17 CALEM ARABIAN DUNCOLIM BOMA ARABIAN DUNCOLIM BOMA MACASANA SANTONA MACASANA SANTONA GAUNDAULIM GAUNDAULIM CURTORIM RUMBEREM