Forbidden Glimpses of Shan State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

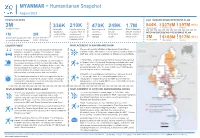

Myanmar – Humanitarian Snapshot (August 2021)

MYANMAR – Humanitarian Snapshot August 2021 PEOPLE IN NEED 2021 HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE PLAN 3M 336K 210K 470K 249K 1.7M 944K $276M $97M (35%) People targeted Requirements Received People in need Internally People internally Non-displaced Returnees and Other vulnerable displaced displaced due to stateless locally people, mostly in INTERIM EMERGENCY RESPONSE PLAN 1M 2M people at the clashes and persons in integrated urban and peri- start of 2021 Rakhine people urban areas people previously identified people identified insecurity since 2M $109M $17M (15%) February 2021 in conflict-affected areas since 1 February People targeted Requirements Received COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT IN KACHIN AND SHAN A total of 3 million people are targeted for humanitarian The overall security situation in Kachin and Shan states assistance across the country. This includes 1 million remains volatile, with various level of clashes reported between people in need in conflict-affected areas previously MAF and ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) or among EAOs. identified and a further 2 million people since 1 February. Monsoon flash floods affected around 125,000 people in In Shan State, small-scale population movement was reported the regions and states of Kachin, Kayin, Mandalay, Mon, in Hsipaw, Muse, Kyethi and Mongkaing townships since mid- Rakhine, eastern Shan and Tanintharyi between late July July. In total, 24,950 people have been internally displaced and mid-August, according to local actors. Immediate across Shan State since the start of 2021; over 5,000 people needs of families affected or evacuated have been remain displaced in five townships. addressed by local aid workers and communities. In Kachin, no new displacement has been reported. -

Shan State - Myanmar

Myanmar Information Management Unit SHAN STATE - MYANMAR Mohnyin 96°40'E Sinbo 97°30'E 98°20'E 99°10'E 100°0'E 100°50'E 24°45'N 24°45'N Bhutan Dawthponeyan India China Bangladesh Myo Hla Banmauk KACHIN Vietnam Bamaw Laos Airport Bhamo Momauk Indaw Shwegu Lwegel Katha Mansi Thailand Maw Monekoe Hteik Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Konkyan Cambodia 24°0'N Muse 24°0'N Muse Manhlyoe (Manhero) Konkyan Namhkan Tigyaing Namhkan Kutkai Laukkaing Laukkaing Mabein Tarmoenye Takaung Kutkai Chinshwehaw CHINA Mabein Kunlong Namtit Hopang Manton Kunlong Hseni Manton Hseni Hopang Pan Lon 23°15'N 23°15'N Mongmit Namtu Lashio Namtu Mongmit Pangwaun Namhsan Lashio Airport Namhsan Mongmao Mongmao Lashio Thabeikkyin Mogoke Pangwaun Monglon Mongngawt Tangyan Man Kan Kyaukme Namphan Hsipaw Singu Kyaukme Narphan Mongyai Tangyan 22°30'N 22°30'N Mongyai Pangsang Wetlet Nawnghkio Wein Nawnghkio Madaya Hsipaw Pangsang Mongpauk Mandalay CityPyinoolwin Matman Mandalay Anisakan Mongyang Chanmyathazi Ai Airport Kyethi Monghsu Sagaing Kyethi Matman Mongyang Myitnge Tada-U SHAN Monghsu Mongkhet 21°45'N MANDALAY Mongkaing Mongsan 21°45'N Sintgaing Mongkhet Mongla (Hmonesan) Mandalay Mongnawng Intaw international A Kyaukse Mongkaung Mongla Lawksawk Myittha Mongyawng Mongping Tontar Mongyu Kar Li Kunhing Kengtung Laihka Ywangan Lawksawk Kentung Laihka Kunhing Airport Mongyawng Ywangan Mongping Wundwin Kho Lam Pindaya Hopong Pinlon 21°0'N Pindaya 21°0'N Loilen Monghpyak Loilen Nansang Meiktila Taunggyi Monghpyak Thazi Kenglat Nansang Nansang Airport Heho Taunggyi Airport Ayetharyar -

Pangolin Trade in the Mong La Wildlife Market and the Role of Myanmar in the Smuggling of Pangolins Into China

Global Ecology and Conservation 5 (2016) 118–126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original research article Pangolin trade in the Mong La wildlife market and the role of Myanmar in the smuggling of pangolins into China Vincent Nijman a, Ming Xia Zhang b, Chris R. Shepherd c,∗ a Oxford Wildlife Trade Research Group, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, UK b Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Gardens, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Mengla, China c TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia article info a b s t r a c t Article history: We report on the illegal trade in live pangolins, their meat, and their scales in the Special Received 7 November 2015 Development Zone of Mong La, Shan State, Myanmar, on the border with China, and Received in revised form 18 December 2015 present an analysis of the role of Myanmar in the trade of pangolins into China. Mong Accepted 18 December 2015 La caters exclusively for the Chinese market and is best described as a Chinese enclave in Myanmar. We surveyed the morning market, wildlife trophy shops and wild meat restaurants during four visits in 2006, 2009, 2013–2014, and 2015. We observed 42 bags Keywords: of scales, 32 whole skins, 16 foetuses or pangolin parts in wine, and 27 whole pangolins for Burma CITES sale. Our observations suggest Mong La has emerged as a significant hub of the pangolin Conservation trade. The origin of the pangolins is unclear but it seems to comprise a mixture of pangolins Manis from Myanmar and neighbouring countries, and potentially African countries. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

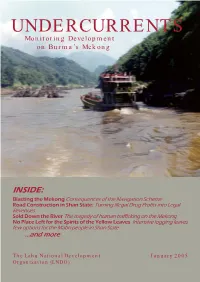

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’S Mekong

UNDERCURRENTS Monitoring Development on Burma’s Mekong INSIDE: Blasting the Mekong Consequences of the Navigation Scheme Road Construction in Shan State: Turning Illegal Drug Profits into Legal Revenues Sold Down the River The tragedy of human trafficking on the Mekong No Place Left for the Spirits of the Yellow Leaves Intensive logging leaves few options for the Mabri people in Shan State ...and more The Lahu National Development January 2005 Organization (LNDO) The Mekong/ Lancang The Mekong River is Southeast Asia’s longest, stretching from its source in Tibet to the delta of Vietnam. Millions of people depend on it for agriculture and fishing, and accordingly it holds a special cultural significance. For 234 kilometers, the Mekong forms the border between Burma’s Shan State and Luang Nam Tha and Bokeo provinces of Laos. This stretch includes the infamous “Golden Triangle”, or where Burma, Laos and Thailand meet, which has been known for illicit drug production. Over 22,000 primarily indigenous peoples live in the mountainous region of this isolated stretch of the river in Burma. The main ethnic groups are Akha, Shan, Lahu, Sam Tao (Loi La), Chinese, and En. The Mekong River has a special significance for the Lahu people. Like the Chinese, we call it the Lancang, and according to legends, the first Lahu people came from the river’s source. Traditional songs and sayings are filled with references to the river. True love is described as stretching form the source of the Mekong to the sea. The beauty of a woman is likened to the glittering scales of a fish in the Mekong. -

Summary of War Crimes by Burma Army During Offensive in Central Shan State Since Oct 6, 2015

Summary of war crimes by Burma Army during offensive in central Shan State since Oct 6, 2015 Shelling/bombing of civilian targets Date Type of attack Targeted civilian area Oct 26, 2015 Shelling, causing civilian injury Wan Mwe Taw village, Waeng Kao tract, Mong Nawng township Oct 28, 2015 Shelling, causing civilian injury Wan Hai village (residential area), Ke See township Nov 9, 2015 Shelling causing damage to Mong Nawng town (est. 6,000 population) civilian houses Nov 10, 2015 Shelling and aerial bombing Mong Nawng town (est. 6,000 population) causing civilian injury and damage to civilian houses and school Nov 10, 2015 Shelling and aerial bombing Wan Saw village, Mong Hsu township (where causing damage to civilian houses over 1,500 displaced villagers were sheltering) Nov 12, 2015 Shelling causing damage to Mong Nawng town (est. 6,000 population) civilian houses Other abuses against civilians by Burma Army troops Date Villagers Type of abuse Location Oct 26, a 53-yr-old man Shot and injured by Wan Koong Nim, Hai Pa tract, Mong Hsu 2015 Burma Army troops township while fleeing shelling Nov 5, a 32-yr-old woman Gang-raped by Burma (village name withheld) Ke See township 2015 Army troops Nov 8, a 55-yr-old woman Shot and injured by Nr. Wan Hoong Kham, Waeng Kao tract, 2015 and a 15-yr-old boy Burma Army troops Mong Nawng township while returning from farm Nov 22, 17 villagers now Shot at by Burma Army Nr Mong Ark, Mong Hsu township 2015 missing, suspected troops while harvesting injured or killed rice Estimated number of internally displaced persons (IDPs) resulting from current offensive in central Shan State (November 23, 2015) No. -

IDP 2011 Eng Cover Master

Map 7 : Southern and Central Shan State Hsipaw Mongmao INDIA Ta ng ya n CHINA Mongyai MYANMAR (BURMA) LAOS M Y A N M A R / B U R M A THAILAND Pangsang Kehsi Mong Hsu Matman Salween Mongyang S H A N S T A T E Mongket COAL MINE Mongla Mong Kung Pang Mong Ping Kunhing Kengtung Yatsauk Laikha Loilem Namzarng Monghpyak Mong Kok COAL MINE Taunggyi KENG TAWNG DAM COAL MINE Nam Pawn Mong Hsat Mongnai TASANG Tachilek Teng DAM Langkher Mongpan Mongton Mawkmai Hsihseng en Salwe Pekon T H A I L A N D Loikaw Kilometers Shadaw Demawso Wieng Hang Ban Mai 01020 K A Y A H S T A T E Nai Soi Tatmadaw Regional Command Refugee Camp Development Projects Associated with Human Rights Abuses Tatmadaw Military OPS Command International Boundary Logging Tatmadaw Battalion Headquarters State/Region Boundary Dam BGF/Militia HQ Rivers Mine Tatmadaw Outpost Roads Railroad Construction BGF/Militia Outpost Renewed Ceasefire Area (UWSA, NDAA) Road Construction Displaced Village, 2011 Resumed Armed Resistance (SSA-N) IDP Camp Protracted Armed Resistance (SSA-S, PNLO) THAILAND BURMA BORDER CONSORTIUM 43 Map 12 : Tenasserim / Tanintharyi Region INDIA T H A I L A N D CHINA MYANMAR Yeb yu (BURMA) LAOS Dawei Kanchanaburi Longlon THAILAND Thayetchaung Bangkok Ban Chaung Tham Hin T A N I N T H A R Y I R E G I O N Gulf Taninth of Palaw a Thailand ryi Mergui Andaman Sea Tanintharyi Mawtaung Bokpyin Kilometers 0 50 100 Kawthaung Development Projects Associated Tatmadaw Regional Command Refugee Camp with Human Rights Abuses Tatmadaw Military OPS Command International Boundary Gas -

Mong La: Business As Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands

Mong La: Business as Usual in the China-Myanmar Borderlands Alessandro Rippa, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich Martin Saxer, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich The aim of this project is to lay the conceptual groundwork for a new understanding of the positionality of remote areas around the globe. It rests on the hypothesis that remoteness and connectivity are not independent features but co-constitute each other in particular ways. In the context of this project, Rippa and Saxer conducted exploratory fieldwork together in 2015 along the China-Myanmar border. This collaborative photo essay is one result of their research. They aim to convey an image of Mong La that goes beyond its usual depiction as a place of vice and unruliness, presenting it, instead, as the outcome of a particular China-inspired vision of development. Infamous Mong La It is 6:00 P.M. at the main market of Mong La, the largest town in the small autonomous strip of land on the Chinese border formally known in Myanmar as Special Region 4. A gambler from China’s northern Heilongjiang Province just woke up from a nap. “I’ve been gambling all morning,” he says, “but after a few hours it is better to stop. To rest your brain.” He will go back to the casino after dinner, as he did for the entire month he spent in Mong La. Like him, hundreds of gamblers crowd the market, where open-air restaurants offer food from all over China. A small section of the market is dedicated to Mong La’s most infamous commodity— wildlife. -

Update by the Shan Human Rights Foundation March 27, 2020 Burma

Update by the Shan Human Rights Foundation March 27, 2020 Burma Army troops shell indiscriminately, loot property, use forced labor during large-scale operation against NCA signatory RCSS/SSA in Mong Kung Since February 27, 2020, about 1,500 Burma Army troops from nine battalions have carried out an operation in Mong Kung, central Shan State, to seize and occupy a mountaintop camp of the Restoration Council of Shan State/Shan State Army (RCSS/SSA). Indiscriminate shelling and shooting forced about 800 villagers to flee their homes, after which troops looted their property. 17 villages have been forced to provide bamboo to the Burma Army to fortify the camp seized from RCSS/SSA. The operation was authorized at the highest level, involving nine battalions from three regional commands: Light Infantry Battalions (LIB) 520, 574, 575 from the Taunggyi-based Eastern Command; LIB 136, LIB 325, IB 22, IB 33 from the Lashio-based Northeastern Command; and LIB 246, 525 from the Kho Lam-based Eastern Central Command. The camp seized from the RCSS/SSA lies on the strategic mountaintop of Loi Don, between Mong Kung, Ke See and Hsipaw townships. One year ago, in March 2019, the Burma Army launched a similar attack to seize the Pang Kha mountain base of the Shan State Progress Party/Shan State Army (SSPP/SSA), about 10 kilometers north of Loi Don. This is despite the fact that both Shan armies have bilateral ceasefire agreements with the government, and the RCSS/SSA has signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). The Burma Army’s brazen violation of existing ceasefires, in order to expand their military infrastructure in Shan State, shows their clear insincerity towards the peace process. -

The United Nations in Myanmar

The United Nations in Myanmar United Nations Resident & Humanitarian Coordinator LEGEND Ms. Renata Dessallien Produced by : MIMU Date : 4 May 2016 Field Presence (By Office/Staff) Data Source : UN Agencies in Myanmar The United Nations (UN) has been present in Myanmar and assisting vulnerable populations since the country gained its independence in 1948. Head Office The UN Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator (UN RC/HC) is the chief UN official in Myanmar for humanitarian, recovery and Development activities. The UN country-level coordination is managed by the UN Country Team (UNCT) and led by the UN RC/HC. OTHER ENTITIES AND ASSOCIATE COORDINATION FUNDS AND PROGRAMMES SPECIALIZED AGENCIES AGENCIES UN- World UNRC /HC UNO CHA UN IC MIM U UND SS UNIC EF UN DP UNH CR UNO DC UNF PA WF P UNE SCO FA O UNI DO ILO WH O UNA IDS OHC HR UNO PS U N IO M IM F Office of the UN Coordin ation of Informatio n Centre Inform ation Safety and Children 's Fund Develo pment High Com missioner HABI TAT Office on D rugs and Population Fund World Food Educationa l, Scientific Food & Ag ricultural Industrial D evelopment Internation al Labour World Health Joint Prog ramme on High Com missioner Office for Project Interna tional Ban k Intern ational Resident/Humanitarian Humanitarian Affairs Management Unit Security Programme for Refugees Human Settlements Crime Programme & Cultural Organization Organization Organization Organization Organization HIV/AIDS for Human Rights Services WOMEN Organization for Monetary Fund Coordinator Programme Migration Group MANDATES To -

China Thailand Laos

MYANMAR IDP Sites in Shan State As of 30 June 2021 BHUTAN INDIA CHINA BANGLADESH MYANMAR Nay Pyi Taw LAOS KACHIN THAILAND CHINA List of IDP Sites In nothern Shan No. State Township IDP Site IDPs 1 Hseni Nam Sa Larp 267 2 Hsipaw Man Kaung/Naung Ti Kyar Village 120 3 Bang Yang Hka (Mung Ji Pa) 162 4 Galeng (Palaung) & Kone Khem 525 5 Galeng Zup Awng ward 5 RC 134 6 Hu Hku & Ho Hko 131 SAGAING Man Yin 7 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church) 245 Man Pying Loi Jon 8 Kutkai downtown (KBC Church-2) 155 Man Nar Pu Wan Chin Mu Lin Huong Aik 9 Mai Yu Lay New (Ta'ang) 398 Yi Hku La Shat Lum In 22 Nam Har 10 Kutkai Man Loi 84 Ngar Oe Shwe Kyaung Kone 11 Mine Yu Lay village ( Old) 264 Muse Nam Kut Char Lu Keng Aik Hpan 12 Mung Hawm 170 Nawng Mo Nam Kat Ho Pawt Man Hin 13 Nam Hpak Ka Mare 250 35 ☇ Konkyan 14 Nam Hpak Ka Ta'ang ( Aung Tha Pyay) 164 Chaung Wa 33 Wein Hpai Man Jat Shwe Ku Keng Kun Taw Pang Gum Nam Ngu Muse Man Mei ☇ Man Ton 15 New Pang Ku 688 Long Gam 36 Man Sum 16 Northern Pan Law 224 Thar Pyauk ☇ 34 Namhkan Lu Swe ☇ 26 Kyu Pat 12 KonkyanTar Shan Loi Mun 17 Shan Zup Aung Camp 1,084 25 Man Set Au Myar Ton Bar 18 His Aw (Chyu Fan) 830 Yae Le Man Pwe Len Lai Shauk Lu Chan Laukkaing 27 Hsi Hsar 19 Shwe Sin (Ward 3) 170 24 Tee Ma Hsin Keng Pang Mawng Hsa Ka 20 Mandung - Jinghpaw 147 Pwe Za Meik Nar Hpai Nyo Chan Yin Kyint Htin (Yan Kyin Htin) Manton Man Pu 19 Khaw Taw 21 Mandung - RC 157 Aw Kar Shwe Htu 13 Nar Lel 18 22 Muse Hpai Kawng 803 Ho Maw 14 Pang Sa Lorp Man Tet Baing Bin Nam Hum Namhkan Ho Et Man KyuLaukkaing 23 Mong Wee Shan 307 Tun Yone Kyar Ti Len Man Sat Man Nar Tun Kaw 6 Man Aw Mone Hka 10 KutkaiNam Hu 24 Nam Hkam - Nay Win Ni (Palawng) 402 Mabein Ton Kwar 23 War Sa Keng Hon Gyet Pin Kyein (Ywar Thit) Nawng Ae 25 Namhkan Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) 338 Si Ping Kaw Yi Man LongLaukkaing Man Kaw Ho Pang Hopong 9 16 Nar Ngu Pang Paw Long Htan (Tart Lon Htan) 26 Nam Hkam (KBC Jaw Wang) II 32 Ma Waw 11 Hko Tar Say Kaw Wein Mun 27 Nam Hkam Catholic Church ( St. -

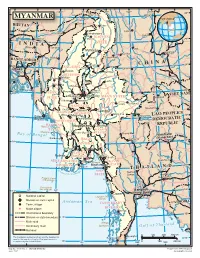

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations.