P. Carey the Sepoy Conspiracy of 1815 in Java In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Indian War of Independence”: the First

FOR DISCUSSION ONLY. V.D.SAVARKAR’S “ THE INDIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE”: THE FIRST NATIONALIST RECONSTRUCTION OF REVOLT OF 1857. Bhagwan Josh Centre for Historical Studies J.N.U. New Delhi. In India, History invariably evokes political passions in the public domain. One of the reasons for this is that the popular conception of history in the mass imagination continues to be an act of recognition and celebration of the spirit of selfless service, bravery and sacrifice on the part of individuals, families, castes, communities and political parties. History writing is considered as an important mode of appropriating, accumulating and constantly renewing “the cultural capital”, the durable stuff that goes into the making of contemporary political discourses in India. Savarkar’s “The Indian War of Independence” was an important book written in this tradition. In March, 2003, when a portrait of the Hindutva Hero Veer Savarkar in Parliament’s Central Hall was unveiled, the public opinion was sharply polarised between those who sang his praises and others who denounced him for his role in the Indian national movement and Gandhi murder. For his followers, Veer Savarkar(1883-1966) continues to be a figure of great reverence despite the fact that he was included as a co-conspirator in the assassination of Gandhi.: a patriot, prolific writer, historian, motivator, and above all an individual with a revolutionary faith in the motherland. The book was written originally in Marathi, in 1908, when Savarkar was about twenty-five years of age and was living in London. The English translation of the book was printed in Holland and a large number of copies were smuggled into India. -

Early Revolts Against British Rule in Tamil Nadu Unit

Unit - 6 Early Revolts against British Rule in Tamil Nadu Learning Objectives To acquaint ourselves with Palayakkarar system and the revolts of Palayakkarars against the British Velunachiyar, Puli Thevar, Kattabomman and Marudhu Brothers in the anti-British uprisings Vellore Revolt as a response to British pacification of south India Introduction Palayakkarars (Poligar is how the British After defeating the French and their referred to them) Indian allies in the three Carnatic Wars, the in Tamil refers to East India Company began to consolidate the holder of a little and extend its power and influence. However, kingdom as a feudatory local kings and feudal chieftains resisted this. to a greater sovereign. The first resistance to East India Company’s Under this system, territorial aggrandisement was from Puli palayam was given Thevar of Nerkattumseval in the Tirunelveli for valuable military Viswanatha Nayaka region. This was followed by other chieftains services rendered by any individual. in the Tamil country such as Velunachiyar, This type of Palayakkarars system was in Veerapandiya Kattabomman, the Marudhu practice during the rule of Prataba Rudhra brothers, and Dheeran Chinnamalai. Known of Warangal in the Kakatiya kingdom. as the Palayakkarars Wars, the culmination The system was put in place in Tamilnadu of which was Vellore Revolt of 1806, this by Viswanatha Nayaka, when he became early resistance to British rule in Tamilnadu the Nayak ruler of Madurai in 1529, with is dealt with in this lesson. the support of his minister Ariyanathar. Resistance of Traditionally there were supposed to be 72 Palayakkarars. 6.1 Regional Powers The Palayakkarars were free to collect against the British revenue, administer the territory, settle disputes and maintain law and order. -

The Black Hole of Empire

Th e Black Hole of Empire Th e Black Hole of Empire History of a Global Practice of Power Partha Chatterjee Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford Copyright © 2012 by Princeton University Press Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW press.princeton.edu All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Chatterjee, Partha, 1947- Th e black hole of empire : history of a global practice of power / Partha Chatterjee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-691-15200-4 (hardcover : alk. paper)— ISBN 978-0-691-15201-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Bengal (India)—Colonization—History—18th century. 2. Black Hole Incident, Calcutta, India, 1756. 3. East India Company—History—18th century. 4. Imperialism—History. 5. Europe—Colonies—History. I. Title. DS465.C53 2011 954'.14029—dc23 2011028355 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available Th is book has been composed in Adobe Caslon Pro Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To the amazing surgeons and physicians who have kept me alive and working This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Preface xi Chapter One Outrage in Calcutta 1 Th e Travels of a Monument—Old Fort William—A New Nawab—Th e Fall -

Governor-General and Viceroy of India

www.gradeup.co Governor-General and Viceroy of India Governors of Bengal (1757–74) Robert Clive • Governor of Bengal during 1757–60 and again during 1765–67 and established Dual Government in Bengal from 1765–72. • Clive’s initial stay in India lasted from 1744 to 1753. • He was called back to India in 1755 to ensure British supremacy in the subcontinent against the French. • In 1757, Clive along with Admiral Watson was able to recapture Calcutta from the Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah. • In the Battle of Plassey, the Nawab was defeated by the British despite having a larger force. • Clive ensured an English victory by bribing the Nawab’s army commander Mir Jaffar, who was installed as Bengal’s Nawab after the battle. • Clive was also able to capture some French forts in Bengal. • For these exploits, Robert Clive was made Lord Clive, Baron of Plassey. • As a result of this battle, the British became the paramount power in the Indian subcontinent. • Bengal became theirs and this greatly increased the company’s fortunes. (Bengal was richer than Britain at that time). • This also opened up other parts of India to the British and finally led to the rise of the British Raj in India. For this reason, Robert Clive is also known as “Conqueror of India”. • Vansittart (1760–65): The Battle of Buxar (1764). • Cartier (1769–72): Bengal Famine (1770). Governors-General of Bengal (1774–1833) Warren Hastings (1772–1785) • First Governor General of Bengal. • Brought the Dual Government of Bengal to an end by the Regulating Act, 1773 • Became Governor-General in 1774 through the Regulating Act, 1773. -

8Th History Term 3 Lessons 1 2 3 4 5 6 In

Winmeen VAO Mission 100 2018 8th Std – Term 3 – Lesson 1 1. Lord William Bentinck (A.D. 1828 to 1835 A.D.) 1. First Burma War – A.D. 1824 2. Who created a post of law member in the executive council of the Governor-General of Charter Act of 1833? Lord Macaulay 3. Sati Prohibition Act – 1829 A.D. 4. Who fought against abolition of female infanticide? Lord William Bentinck 5. Under whose control did Lord William Bentinck fought against the Thugs? Major Sleeman 6. With whom did the Indian compare Lord William Bentinck? Lord Ripon 7. Under whose rule did they introduce the Charter Act of 1833? Lord William Bentinck 8. Which language did Lord William Bentinck remove to introduce vernacular language? Persian language 8th Std – Term 3 – Lesson 2 2. Lord Dalhousie A.D. 1848 to 1855 A.D. 1. In which year did Lord Dalhousie become the Governor General of India? A.D. 1848 2. Doctrine of Lapse - Lord Dalhousie 3. What was the result of the Doctrine of Lapse revolt? 1 www.winmeen.com | Paid Copy – Don’t Share With Anyone Winmeen VAO Mission 100 2018 Great Revolt of 1857 4. Second Burmese War – A.D. 1852 5. Simla – Summer Capital 6. Calcutta – Winter Capital 7. Who introduced railways into India? Lord Dalhousie 8. The first railway line was laid in 1853 A.D. between Bombay to Thane. In 1854 A.D. a railway line was laid from Howrah to Ranikanj . In 1856 A.D. a railway line was laid from Madras to Arakonam. 9. Who is the `Father of Indian Railways`? Lord Dalhousie 10. -

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities ISSN 2277 – 9809 (online) ISSN 2348 - 9359 (Print) An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust www.IRJMSH.com www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions IRJMSH YEAR [2012] Volume 3 Issue 2 online ISSN 2277 – 9809 LOYALTY AND DISCONTENT IN THE MADRAS ARMY OF VELLORE MUTINY Jadhav Nagendra Krishna1, MS Prashanth2 and Abraham Kulluvattum1 1Department of History, Bundelkhand University, Jansi, U.P. 2V K Chanvan- Patil Arts, Commerce and Science College, Karve-416507, Kolhapur, Maharashtra Abstract The nearness of the banished group of the late Tipu Sultan may likewise have added to the current of threatening vibe. Tipu Sultan`s children were detained at the Vellore stronghold since 1799. One of Tipu Sultan`s little girls was to be hitched on July 9 1806. The plotters of the mutiny amassed at the fortress under the stratagem of going to the wedding. Two hours after 12 pm, on July 10, the sepoys (warriors) encompassed the fortification and killed the greater part of the British. The agitators seized control by sunrise and raised the banner of the Mysore Sultanate over the fortress. Tipu`s second child Fateh Hyder was proclaimed King. Notwithstanding, a British officer had gotten away and cautioned the battalion in Arcot. After nine hours, the British nineteenth Light Dragoons, driven by Colonel Gillespie and the Madras Cavalry entered the stronghold through entryways that had not been completely secured by the sepoys. The staying of the Vellore Mutiny was an inevitable end product. After the episode, the detained royals were exchanged to Calcutta. -

Governors of Bengal

Governor Generals of Bengal (1757 -1833) Governors of Bengal Founder of the British Indian Empire, Served as Civil Servant, Military head and First Governor of Bengal for the East India Company (EIC) Administration ROBERT CLIVE (1757- 60, 1765 - 67) revenue Battle of Plassey (1757) marked the EIC got right to collect revenue at beginning of British Rule in India ` Bengal, Bihar and Orissa under under Clive administration. ` Treaty of Allahabad (1765). Dual Administration in Bengal (1765-1772) marked the beginning of the Economic loot in India, the Company got Diwani jurisdiction while the Nawab is left with territorial jurisdiction. Governor - GeneralS of Bengal The last Governor of Bengal (1772 – 74) and the rst Governor-General of Bengal (1774) The Only Governor General against him impeachment proceeding were initiated in England. His period is called “Trial & Error” WARREN HASTINGS (1772-1785) Administration Regulating Act of 1773 - An Act to regulate affairs of EIC in India by British Crown, created ofce of Governor General of Bengal, abolished Dual system in Bengal. Appointed collectors to Pitt's India Act of 1784 - collect revenue and look To rectify the defects into judicial affairs. of 1773 Act. Established Board of Control Subordination of Presidency in Britain to supervise of Bombay and Madras under Company's affairs in India. Governor - General. Judiciary Established Civil and Criminal Courts in each district and the Supreme Court at Calcutta in 1774. Education Established Calcutta Madrasa, the rst educational institute by the Company in 1781 for the promotion of Islamic studies & Asiatic Society of Bengal with William Jones (1784) to understand Indian Culture; First English Translation of Bhagwat Gita. -

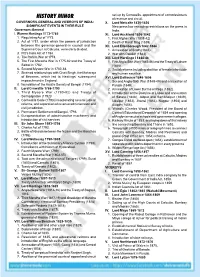

HISTORY MINOR of Revenue and Circuit

set up by Cornwallis, appointment of commissioners HISTORY MINOR of revenue and circuit. GOVERNORS-GENERAL AND VICEROYS OF INDIA : X. Lord Metcalfe 1835-1836 SIGNIFICANT EVENTS IN THEIR RULE New press law removing restrictions on the press in Governors-General India. I. Warren Hastings 1773-1785 XI. Lord Auckland 1836-1842 1. Regulating Act of 1773. 1. First Afghan War (1838-42) 2. Act of 1781, under which the powers of jurisdiction 2. Death of Ranjit Sing (1839). between the governor-general-in council and the XII. Lord Ellenborough 1842-1844 Supreme Court at Calcutta, were clerly divided. 1. Annexation of Sindh (1843). 3. Pitt's India Act of 1784. 2. War with Gwalior (1843). 4. The Rohilla War of 1774. XIII. Lord Hardinge I 1844-48 5. The First Maratha War in 1775-82 and the Treaty of 1. First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-46) and the Treaty of Lahore Salbai in 1782. (1846). 6. Second Mysore War in 1780-84. 2. Social reforms including abolition of female infanticide 7. Strained relationships with Chait Singh, the Maharaja and human sacrifice. of Benaras, which led to Hastings' subsequent XVI. Lord Dalhousie 1848-1856 impeachment in England. 1. Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-49) and annexation of 8. foundation of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (1784). Punjab (1849). II. Lord Crnwallis 1786-1793 2. Annexation of Lower Burma or Pegu (1852). 1. Third Mysore War (1790-92) and Treaty of 3. Introduction of the Doctrine of Lapse and annexation Seringapatam (1792)/ of Satara (1848), Jaitpur and Sambhalpur (1849), 2. Cornwallis Code (1793) incorporating several judicial Udaipur (1852), Jhansi (1853), Nagpur (1854) and reforms, and separation of revenue administration and Awadh (1856). -

![Vellore Mutiny - 1806 [NCERT Notes on Modern Indian History for UPSC]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8034/vellore-mutiny-1806-ncert-notes-on-modern-indian-history-for-upsc-3078034.webp)

Vellore Mutiny - 1806 [NCERT Notes on Modern Indian History for UPSC]

UPSC Civil Services Examination UPSC Notes [GS-I] Topic: Vellore Mutiny - 1806 [NCERT Notes on Modern Indian History for UPSC] The Vellore Mutiny predated the Indian Revolt of 1857 by about 50 years. It erupted on 10th July 1806 in Vellore, present-day Tamil Nadu, and lasted only for a day, but it was brutal and shook the British East India Company. It was the first major mutiny by the Indian sepoys in the East India Company. This article talks about Vellore Mutiny, 1806. This topic is an important part of the NCERT notes relevant for the IAS aspirants. These notes will also be useful for other competitive exams like banking PO, SSC, state civil services exams and so on. Vellore Mutiny Causes The major causes for the Vellore mutiny are stated below: The English disregard to the religious sensitivities of the Hindu and Muslim Indian sepoys. Sir John Craddock, the Commander-in-Chief of the Madras Army had issued orders prohibiting soldiers from wearing religious marks on their foreheads and also to trim their moustaches and shave off their beards. This offended both Hindu and Muslim soldiers. They were also asked to wear new round hats instead of the traditional headgear that they were used to. This led to suspicion among the sepoys that they were being converted to Christianity. Craddock was acting against warning from the military board not to bring about changes in the military uniform without taking into consideration all required precautions of Indian sensibilities. A few sepoys who had protested against these new orders were taken to Fort St. -

Fist War of Independence Study Materials

Fist War of Independence Study Materials FIRST WAR OF INDEPENDENCE firangi ko. They broke open jails, murdered European The uprising, which seriously threatened men and women, burnt their houses and marched to British rule in India, has been called by many names Delhi. Next morning, in Delhi the soldiers signalled by historians, including the Sepoy Rebellion, the Great the local soldiers by marching, who in turn revolted, Mutiny and the Revolt of 1857; however, many prefer seized the city and proclaimed the 80-year-old call itIndia’s first war of independence. Undoubtedly, Bahadur Shah Zafar, as the Emperor of India. it was the culmination of mourning Indian resentment toward, British economic and social policies over Popular Movements And Revolts Upto many decades. Until the rebellion the British had 1857 Year Movement/Mutiny succeeded in suppressing numerous and ‘tribal’ wars 1764 Mutiny of sepoys in Bengal or in accommodating them through concessions till the 1766 Chuar and Ro rising in Chhotanogpur and Great Mutiny in the summer of 1857 during the Singbhum regions where the Chaur.He and viceroyalty of Lord Canning. Munda tribes revolted till 1772 due to ` Important Leaders Connected with the famine, enhanced demands and economic ` Revolt privation 1770 Sanyasi Revolt ` The heroine of this war of independence was Rani 1806 Vellore Mutiny ` Lakshmi Bai of Jhansi who died on 17 June 1858, 1817 Bhil movement in the Western Ghats ` 1822 Romosi rising under the leadership of while fighting the British forces. Other notable ` Chittar Singh leaders were Ahmadullah of Awadh, Nana Sahob of ` 1824 Mutiny of sepoys of the 47th Regiment at Konpur and his loyol commander Tantia Tope, Rao Barrackpore ` Singh, Azimullah Khan, Kunwar Singh of ` Jagdishpur, Firuz Shah, Maulwi Ahmed Shah of 1828 Ahams Revolt against the company for non- ` Firozabad; the Begum of Awadh (Hazrat Mahal), fulfilment of pledges after the Burmese War ` Khan Bahadur Khan of Bareilly and Maulawi 1829. -

Colonialism and Nationalism in Modern India

COLONIALISM AND NATIONALISM IN MODERN INDIA STUDY MATERIAL II M A HISTORY Dr. R. Kanchana Devi Assistant Professor, Department of History, Periyar Arts College, Cuddalore. CONTENTS 1. Colonialism and Nationalism 2. South Indian Rebellion (1801) and Vellore Munity (1806) 3. Revolt of 1857 4. Civil Rebellions and Tribal Uprisings 5. Peasant Movements and uprisings after 1857 6. Birth of Indian National Congress and National Movement 7. Moderate and Extremist programme of congress 8. The Roll of Press 9. Rise and Growth of Communalist 10. The impact of First World War and Home Rule Movement 11. Non co-operation Movement and Swaraj Party 12. Peasant Movements and Nationalism in the 1920’s 13. Civil Disobedience Movement 14. The Crisis at Tripuri to the Cripps Mission 15. Quit India Movement and Dawn of Independence COLONIALISM AND NATIONALISM Historical Background For centuries India remained under the influence of Mohammedans and Britishers. Though India has a rich past and at the height of its glory she was one of the most advanced nations of the world yet with the passage of time her glory faded. Not only this but due to internal disunity the invaders could rale over India for centuries together. History is a witness that even at the darkest period of her history Indians continued their struggle for independence in one way for the other and did not agree to accept the fate to which they had been so unfortunately placed. Out modern Indian political thought Practically began with Gokhale who can be called the pioneer of our national movement and subsequently India produced very many political thinkers who continued their struggle against British Imperialism both under the flag of Indian National Congress and even outside that. -

History of Tamilnadu (1800

STUDY MATERIAL FOR B.A. HISTORY HISTORY OF TAMILNADU 1800 - 1967 A.D. SEMESTER - III, ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 UNIT CONTENT PAGE NO I SOUTH INDIAN REBELLION 02 II SOCIO-RELIGIOUS MOVEMENTS 11 III TAMIL ANDU IN FREEDOM STRUGGLE 14 IV TAMIL NADU UNDER CONGRESS RULE 21 V RISE OF DMK TO POWER 27 Page 1 of 29 STUDY MATERIAL FOR B.A. HISTORY HISTORY OF TAMILNADU 1800 - 1967 A.D. SEMESTER - III, ACADEMIC YEAR 2020-21 UNIT - I SOUTH INDIAN REVOLT SOUTH INDIAN REVOLT The South Indian Rebellion of 1800-1801 represented a violent reaction against the surrender of the rulers to the British and loss of freedom. As a result of diplomacy and wars, the aliens established their sway over the land. The horrors that attended the growth of imperialism spread a wave of revulsion and led the inhabitants to united action. The outbreak of the Rebellion marked the climax of a determined Endeavour, made by the common people of South India to liberate the Peninsula of JambuDwipa‘ from British yoke and to forestall the fall of rest of India under European authority, so that all the inhabitants of the land, as the rebels declared, could live ―in constant happiness without tears‖. MaruduPandyan of Sivaganga, Gopala Nayak of Dindigul, Khan –i-Jahan of Coimbatore, Kerala Varma of Malabar, KrishnappaNayak of Mysore and Dhondajiwaug of Maharashtra, who organized a formidable confederacy for the overthrow of the British rule, spearheaded the movement. They held a conspiracy at Virupakshi in Dindigul and rose in arms with an attack on Coimbatore on the 3rd of June, 1800.