The Question That Divided Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coalition Politics: How the Cameron-Clegg Relationship Affects

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Bennister, M. and Heffernan, R. (2011) Cameron as Prime Minister: the intra- executive politics of Britain’s coalition. Parliamentary Affairs, 65 (4). pp. 778-801. ISSN 0031-2290. Link to official URL (if available): http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsr061 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Cameron as Prime Minister: The Intra-Executive Politics of Britain’s Coalition Government Mark Bennister Lecturer in Politics, Canterbury Christ Church University Email: [email protected] Richard Heffernan Reader in Government, The Open University Email: [email protected] Abstract Forming a coalition involves compromise, so a prime minister heading up a coalition government, even one as predominant a party leader as Cameron, should not be as powerful as a prime minister leading a single party government. Cameron has still to work with and through ministers from his own party, but has also to work with and through Liberal Democrat ministers; not least the Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg. The relationship between the prime minister and his deputy is unchartered territory for recent academic study of the British prime minister. This article explores how Cameron and Clegg operate within both Whitehall and Westminster: the cabinet arrangements; the prime minister’s patronage, advisory resources and more informal mechanisms. -

The Ship 2014/2015

A more unusual focus in your magazine this College St Anne’s year: architecture and the engineering skills that make our modern buildings possible. The start of our new building made this an obvious choice, but from there we go on to look at engineering as a career and at the failures and University of Oxford follies of megaprojects around the world. Not that we are without the usual literary content, this year even wider in range and more honoured by awards than ever. And, as always, thanks to the generosity and skills of our contributors, St Anne’s College Record a variety of content and experience that we hope will entertain, inspire – and at times maybe shock you. My thanks to the many people who made this issue possible, in particular Kate Davy, without whose support it could not happen. Hope you enjoy it – and keep the ideas coming; we need 2014 – 2015 them! - Number 104 - The Ship Annual Publication of the St Anne’s Society 2014 – 2015 The Ship St Anne’s College 2014 – 2015 Woodstock Road Oxford OX2 6HS UK The Ship +44 (0) 1865 274800 [email protected] 2014 – 2015 www.st-annes.ox.ac.uk St Anne’s College St Anne’s College Alumnae log-in area Development Office Contacts: Lost alumnae Register for the log-in area of our website Over the years the College has lost touch (available at https://www.alumniweb.ox.ac. Jules Foster with some of our alumnae. We would very uk/st-annes) to connect with other alumnae, Director of Development much like to re-establish contact, and receive our latest news and updates, and +44 (0)1865 284536 invite them back to our events and send send in your latest news and updates. -

1 Why Media Researchers Don't Care About Teletext

1 Why Media Researchers Don’t Care About Teletext Hilde Van den Bulck & Hallvard Moe Abstract This chapter tackles the paradoxical observation that teletext in Europe can look back on a long and successful history but has attracted very little academic interest. The chapter suggests and discusses reasons why media and commu- nications researchers have paid so little attention to teletext and argue why we should not ignore it. To this end, it dissects the features of teletext, its history, and contextualizes these in a discussion of media research as a field. It first discusses institutional (sender) aspects of teletext, focusing on the perceived lack of attention to teletext from a political economic and policy analysis perspective. Next, the chapter looks at the characteristics of teletext content (message) and reasons why this failed to attract the attention of scholars from a journalism studies and a methodological perspective. Finally, it discusses issues relating to the uses of teletext (receivers), reflecting on the discrepancy between the large numbers of teletext users and the lack of scholarly attention from traditions such as effect research and audience studies. Throughout, the chapter points to instances in the development of teletext that constitute so- called pre-echoes of debates that are considered pressing today. These issues are illustrated throughout with the case of the first (est.1974) and, for a long time, leading teletext service Ceefax of the BBC and the wider development of teletext in the UK. Keywords: teletext, communication studies, research gaps, media history, Ceefax, BBC Introduction When we first started thinking about a book on teletext, a medium that has been very much part of people’s everyday lives across Europe for over forty years, we were surprised by the lack of scholarly attention or even interest. -

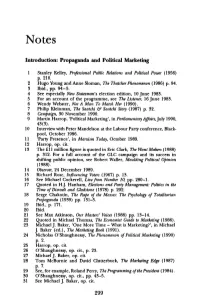

Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing

Notes Introduction: Propaganda and Political Marketing 2 Stanley Kelley, Professional Public Relations and Political Power (1956) p. 210. 2 Hugo Young and Anne Sloman, The Thatcher Phenomenon (1986) p. 94. 3 Ibid., pp. 94-5. 4 See especially New Statesman's election edition, 10 June 1983. 5 For an account of the programme, see The Listmer, 16 June 1983. 6 Wendy Webster, Not A Man To Matcll Her (1990). 7 Philip Kleinman, The Saatchi & Saatchi Story (1987) p. 32. 8 Campaign, 30 November 1990. 9 Martin Harrop, 'Political Marketing', in ParliamentaryAffairs,July 1990, 43(3). 10 Interview with Peter Mandelson at the Labour Party conference, Black- pool, October 1986. 11 'Party Presence', in Marxism Today, October 1989. 12 Harrop, op. cit. 13 The £11 million figure is quoted in Eric Clark, The Want Makers (1988) p. 312. For a full account of the GLC campaign and its success in shifting public opinion, see Robert Waller, Moulding Political Opinion (1988). 14 Obse1ver, 24 December 1989. 15 Richard Rose, Influencing Voters (1967) p. 13. 16 See Michael Cockerell, Live from Number 10, pp. 280-1. 17 Quoted in HJ. Hanham, Ekctions and Party Management: Politics in the Time of Disraeli and Gladstone ( 1978) p. 202. 18 Serge Chakotin, The Rape of the Masses: The Psychology of Totalitarian Propaganda (1939) pp. 131-3. 19 Ibid., p. 171. 20 Ibid. 21 See Max Atkinson, Our Masters' Voices (1988) pp. 13-14. 22 Quoted in Michael Thomas, The Economist Guide to Marketing (1986). 23 Michael J. Baker, 'One More Time- What is Marketing?', in Michael J. -

The Speaker of the House of Commons: the Office and Its Holders Since 1945

The Speaker of the House of Commons: The Office and Its Holders since 1945 Matthew William Laban Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2014 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, Matthew William Laban, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of this thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: Details of collaboration and publications: Laban, Matthew, Mr Speaker: The Office and the Individuals since 1945, (London, 2013). 2 ABSTRACT The post-war period has witnessed the Speakership of the House of Commons evolving from an important internal parliamentary office into one of the most recognised public roles in British political life. This historic office has not, however, been examined in any detail since Philip Laundy’s seminal work entitled The Office of Speaker published in 1964. -

British History, Tradition and Culture Parliament and Government

British history, tradition and culture What should you watch? What does it tell you about? What is the format? Where can you watch it? Andrew Marr’s History of How has Britain changed since 1945 and what role has Television documentary Available as part of a DVD box set from Amazon Modern Britain politics played in that process? Five one-hour episodes from £26.37 or as a standalone DVD from £17.84 Television drama The reign of Queen Elizabeth II and major events during Three series The Crown this period. How the monarchy, government and politics Available on Netflix Ten episodes per series interact is a key feature of this series. 45-60 minutes per episode Parliament and Government What should you watch? What does it tell you about? What is the format? Where can you watch it? A behind-the-scenes look at the work of Members of Television documentary Inside the Commons Available on DVD from Amazon for £12.64 Parliament and House of Commons officials Four one-hour episodes Like Inside the Commons, this follows some larger-than- Currently being shown on London Live, which you Television documentary Meet the Lords life characters in the House of Lords, one of Britain’s may be able to watch via Sky, Virgin, YouView or Three one-hour episodes oldest, most eccentric and important institutions. Freeview – details here Two episodes are currently available on YouTube Michael Cockerell uncovers the workings of the Home Home Office: The Dark Department The Great Offices of Television documentary Office, the Foreign & Commonwealth Office and the Foreign -

Journalism Studies Key Con Journalism 26/4/05 1:14 Pm Page Ii

BOB FRANKLIN, MARTIN HAMER, MARK HANNA, MARIE KINSEY & JOHN E. RICHARDSON concepts key Key Concepts in Journalism SAGE Studies Key Con Journalism 26/4/05 1:14 pm Page i Key Concepts in Journalism Studies Key Con Journalism 26/4/05 1:14 pm Page ii Recent volumes include: Key Concepts in Social Research Geoff Payne and Judy Payne Fifty Key Concepts in Gender Studies Jane Pilcher and Imelda Whelehan Key Concepts in Medical Sociology Jonathan Gabe, Mike Bury and Mary Ann Elston Key Concepts in Leisure Studies David Harris Key Concepts in Critical Social Theory Nick Crossley Key Concepts in Urban Studies Mark Gottdiener and Leslie Budd Key Concepts in Mental Health David Pilgrim The SAGE Key Concepts series provides students with accessible and authoritative knowledge of the essential topics in a variety of ii disciplines. Cross-referenced throughout, the format encourages critical evaluation through understanding. Written by experienced and respected academics, the books are indispensable study aids and guides to comprehension. Key Con Journalism 26/4/05 1:14 pm Page iii BOB FRANKLIN, MARTIN HAMER, MARK HANNA, MARIE KINSEY AND JOHN E. RICHARDSON Key Concepts in Journalism Studies SAGE Publications London G Thousand Oaks G New Delhi Key Con Journalism 26/4/05 1:14 pm Page iv © Bob Franklin, Martin Hamer, Mark Hanna, Marie Kinsey and John E. Richardson 2005 First published 2005 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. -

100 Years of Government Communication

AZ McKenna 100 Years of Government Communication AZ McKenna John Buchan, the frst Director of Information appointed in 1917 Front cover: A press conference at the Ministry of Information, 1944 For my parents and grandparents © Crown copyright 2018 Tis publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identifed any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. 100 YEARS OF GOVERNMENT COMMUNICATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must frstly record my thanks to Alex Aiken, Executive Director of Government Communication, who commissioned me to write this book. His interest in it throughout its development continues to fatter me. Likewise I am indebted to the Government Communication Service who have overseen the book’s production, especially Rebecca Trelfall and Amelie Gericke. Te latter has been a model of eficiency and patience when it has come to arranging meetings, ordering materials and reading every draft and redraft of the text over the last few months. I am also grateful for the efforts of Gabriel Milland – lately of the GCS – that laid much of the groundwork for the volume. However, I would never even have set foot in the Cabinet Ofice had Tom Kelsey of the Historians in Residence programme at King’s College London not put my name forward. I am also hugely grateful to numerous other people at King’s and within the wider University of London. In particular the contemporary historians of the Department of Political Economy – among them my doctoral supervisors Michael Kandiah and Keith Hamilton – and those associated with the International History Seminar of the Institute of Historical Research (IHR) – Michael Dockrill, Matthew Glencross, Kate Utting as well as many others – have been a constant source of advice and encouragement. -

Psa Awards Winners 2000, 2003 - 2016

PSA AWARDS WINNERS 2000, 2003 - 2016 AWARDS TO POLITICIANS Politician of the Year Sadiq Khan (2016) George Osborne (2015) Theresa May (2014) John Bercow (2012) Alex Salmond (2011) David Cameron and Nick Clegg (2010) Barack Obama (2009) Boris Johnson (2008) Alex Salmond (2007) David Cameron (2006) Tony Blair (2005) Gordon Brown (2004) Ken Livingstone (2003) Lifetime Achievement in Politics Gordon Brown (2016) Harriet Harman (2015) David Blunkett (2014) Jack Straw (2013) Sir Richard Leese (2012) Bill Morris (2012) Chris Patten (2012) David Steel (2011) Michael Heseltine (2011) Neil Kinnock (2010) Geoffrey Howe (2010) Rhodri Morgan (2009) Ian Paisley (2009) Paddy Ashdown (2007) Prof John Hume (2006) Lord David Trimble (2006) Sir Tam Dalyell (2005) Kenneth Clarke QC (2004) Baroness Williams of Crosby (2003) Dr Garrett Fitzgerald (2003) Roy Jenkins (2000) Denis Healey (2000) Edward Heath (2000) Special Award for Lifetime Achievement in Politics Aung San Suu Kyi (2007) 1 Opposition Politician of the Year Theresa May (2003) Parliamentarian of the Year Baroness Smith of Basildon (2016) Sarah Wollaston (2015) Nicola Sturgeon (2014) Natascha Engel (2013) Margaret Hodge (2012) Ed Balls (2011) Patrick Cormack (2010) Dennis Skinner (2010) Tony Wright (2009) Vince Cable (2008) John Denham (2007) Richard Bacon MP (2006) Sir Menzies Campbell (2005) Gwyneth Dunwoody (2005) Baroness Scotland of Asthal QC (2004) Robin Cook (2003) Tony Benn (2000) Political Turkey of the Year Veritas (2005) The Law Lords (2004) Folyrood - the Scottish Parliament building -

“Tony Wants”: the First Blair Premiership in Historical Perspective Transcript

“Tony Wants”: The First Blair Premiership in Historical Perspective Transcript Date: Wednesday, 7 November 2001 - 12:00AM Location: Staple Inn Hall Blair’s First Term Professor Peter Hennessy May I begin this evening with a few words about Professor Colin Matthew. I did not know Colin well ~ but I knew him well enough to appreciate how important he was to my profession. He had a capacity to inspire and to organise both on the page, within his university and through such learned bodies as the Royal Historical Society which was very special indeed. His judgement allied to his energy and generosity of spirit meant that Colin could ~ and did ~ make good things happen like few others. It is a great honour to be speaking in his memory this evening. Ladies and gentlemen, this is a lecture in two parts. Part one is written as if today was the10th September 2001. It will be the sort of presentation I would have given if Black Tuesday had not happened and the political press was still reflecting the running argument between sections of the Labour movement and the government about the precise mix of the still churning New Labour version of a mixed economy. No doubt the papers, too, would have been full of the latest twists and turns of the Tony/Gordon story ~ a political rivalry unmatched perhaps since the Gladstone/Disraeli era, (the period which Colin Matthew covered so wonderfully), the difference being that TB and GB are members of the same Cabinet. We would be intrigued, too, by the new configuration of the ever more tightly fused No.10 and Cabinet Office ~ the latest geographical expression of the Blair Centre. -

Anglo-American Relations and the EC Enlargement, 1969-1974 Name

- 1 - Title: Anglo-American relations and the EC enlargement, 1969-1974 Name: Justin Adam Brummer Institution: UCL Degree: PhD History - 2 - I, Justin Adam Brummer confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. - 3 - Abstract This thesis examines the ramifications of Britain’s negotiations to join the European Community (EC) on Anglo-American relations, 1969-1974. It adds to the historical debate by showing that strong Anglo-American political, economic, and defence relations continued under Heath and Nixon. The prevailing view in this area is that the British Prime Minister Heath sought to re-orientate foreign policy away from the ‘special’ Anglo-American relationship towards the EC. Moreover, it is believed that the Nixon presidency developed a sceptical view of an enlarged, competitive EC. Thus, the Heath-Nixon period is viewed as a low point in the post-1945 alliance because of the EC enlargement. However, while gaining entry into the EC was the top priority for the UK government, Heath and Whitehall sought to preserve close Anglo-American cooperation. Moreover, Nixon considered Western European integration and Anglo-American relations to be important components of the Atlantic Alliance and his Cold War strategy. Tensions did grow: over the substance of China and Middle Eastern policy, the unilateral dismantling of the Bretton Woods system, and the ‘Year of Europe’. But these episodes also showed the strength of the Anglo-American partnership. In the economic sphere the EC enlargement negotiations planted the UK into the middle of US-EC trade conflict over unfair trading practices. -

100 Years of Government Communication

AZ McKenna 100 Years of Government Communication AZ McKenna John Buchan, the frst Director of Information appointed in 1917 Front cover: A press conference at the Ministry of Information, 1944 For my parents and grandparents © Crown copyright 2018 Tis publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/version/3 Where we have identifed any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. 100 YEARS OF GOVERNMENT COMMUNICATION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must frstly record my thanks to Alex Aiken, Executive Director of Government Communication, who commissioned me to write this book. His interest in it throughout its development continues to fatter me. Likewise I am indebted to the Government Communication Service who have overseen the book’s production, especially Rebecca Trelfall and Amelie Gericke. Te latter has been a model of eficiency and patience when it has come to arranging meetings, ordering materials and reading every draft and redraft of the text over the last few months. I am also grateful for the efforts of Gabriel Milland – lately of the GCS – that laid much of the groundwork for the volume. However, I would never even have set foot in the Cabinet Ofice had Tom Kelsey of the Historians in Residence programme at King’s College London not put my name forward. I am also hugely grateful to numerous other people at King’s and within the wider University of London. In particular the contemporary historians of the Department of Political Economy – among them my doctoral supervisors Michael Kandiah and Keith Hamilton – and those associated with the International History Seminar of the Institute of Historical Research (IHR) – Michael Dockrill, Matthew Glencross, Kate Utting as well as many others – have been a constant source of advice and encouragement.