Britishness, the Falklands War, and the Memory of Settler Colonialism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telling the Truth About Class

TELLING THE TRUTH ABOUT CLASS G. M. TAMÁS ne of the central questions of social theory has been the relationship Obetween class and knowledge, and this has also been a crucial question in the history of socialism. Differences between people – acting and knowing subjects – may influence our view of the chances of valid cognition. If there are irreconcilable discrepancies between people’s positions, going perhaps as far as incommensurability, then unified and rational knowledge resulting from a reasoned dialogue among persons is patently impossible. The Humean notion of ‘passions’, the Nietzschean notions of ‘resentment’ and ‘genealogy’, allude to the possible influence of such an incommensurability upon our ability to discover truth. Class may be regarded as a problem either in epistemology or in the philosophy of history, but I think that this separation is unwarranted, since if we separate epistemology and the philosophy of history (which is parallel to other such separations characteristic of bourgeois society itself) we cannot possibly avoid the rigidly-posed conundrum known as relativism. In speak- ing about class (and truth, and class and truth) we are the heirs of two socialist intellectual traditions, profoundly at variance with one another, although often intertwined politically and emotionally. I hope to show that, up to a point, such fusion and confusion is inevitable. All versions of socialist endeavour can and should be classified into two principal kinds, one inaugurated by Rousseau, the other by Marx. The two have opposite visions of the social subject in need of liberation, and these visions have determined everything from rarefied epistemological posi- tions concerning language and consciousness to social and political attitudes concerning wealth, culture, equality, sexuality and much else. -

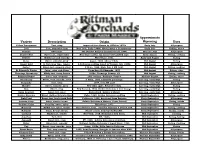

Apples Catalogue 2019

ADAMS PEARMAIN Herefordshire, England 1862 Oct 15 Nov Mar 14 Adams Pearmain is a an old-fashioned late dessert apple, one of the most popular varieties in Victorian England. It has an attractive 'pearmain' shape. This is a fairly dry apple - which is perhaps not regarded as a desirable attribute today. In spite of this it is actually a very enjoyable apple, with a rich aromatic flavour which in apple terms is usually described as Although it had 'shelf appeal' for the Victorian housewife, its autumnal colouring is probably too subdued to compete with the bright young things of the modern supermarket shelves. Perhaps this is part of its appeal; it recalls a bygone era where subtlety of flavour was appreciated - a lovely apple to savour in front of an open fire on a cold winter's day. Tree hardy. Does will in all soils, even clay. AERLIE RED FLESH (Hidden Rose, Mountain Rose) California 1930’s 19 20 20 Cook Oct 20 15 An amazing red fleshed apple, discovered in Aerlie, Oregon, which may be the best of all red fleshed varieties and indeed would be an outstandingly delicious apple no matter what color the flesh is. A choice seedling, Aerlie Red Flesh has a beautiful yellow skin with pale whitish dots, but it is inside that it excels. Deep rose red flesh, juicy, crisp, hard, sugary and richly flavored, ripening late (October) and keeping throughout the winter. The late Conrad Gemmer, an astute observer of apples with 500 varieties in his collection, rated Hidden Rose an outstanding variety of top quality. -

Secrets and Spies Late at Churchill War Rooms Friday 4 October 2013 6.30Pm – 9.30Pm

Immediate release Secrets and Spies at Churchill War Rooms From September 2013, a series of secret and spy-themed events will take place beneath the streets of Whitehall, in Churchill’s secret underground bunker. These events include a lecture from Simon Pearson on his book The Great Escaper, following the sold out lecture by historian, Clare Mulley’s talk on her new book The Spy Who Loved and an espionage themed late night opening. Secrets and Spies Late at Churchill War Rooms Friday 4 October 2013 6.30pm – 9.30pm Churchill War Rooms will present London’s most unique night out this autumn. Experience Churchill War Rooms as never before, step back in time to a world of 1940s espionage and embark on a secret mission to discover if you have what it takes to reach the standard of a Special Operations Executive (SOE) under Churchill’s government. Take part in a spy challenge, decode hidden devices against the clock and seek out spy bugs planted around the site, using GPS devices. Encounter a SOE agent reenacting some of the most famous secret missions of Second World War and watch an official SOE recruitment film from IWM’s archives. In the spirit of the era, there will be 1940s themed drinks and those who complete the spy challenge will be entered into a draw to win a spy-themed weekend away and a private tour of Churchill War Rooms. 1940s vintage attire encouraged. Tickets: Adults, £17 Concessions, £13.60 Simon Pearson - The Great Escaper Tuesday 15 October 2013 7pm – 9pm (Doors open 6.30pm) Author and Times journalist Simon Pearson will discuss the extraordinary story of Roger Bushell, known as Big X, a prisoner of war noted for masterminding the ‘Great Escape’ at the infamous Stalag Luft III camp. -

Coalition Politics: How the Cameron-Clegg Relationship Affects

Canterbury Christ Church University’s repository of research outputs http://create.canterbury.ac.uk Please cite this publication as follows: Bennister, M. and Heffernan, R. (2011) Cameron as Prime Minister: the intra- executive politics of Britain’s coalition. Parliamentary Affairs, 65 (4). pp. 778-801. ISSN 0031-2290. Link to official URL (if available): http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsr061 This version is made available in accordance with publishers’ policies. All material made available by CReaTE is protected by intellectual property law, including copyright law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Contact: [email protected] Cameron as Prime Minister: The Intra-Executive Politics of Britain’s Coalition Government Mark Bennister Lecturer in Politics, Canterbury Christ Church University Email: [email protected] Richard Heffernan Reader in Government, The Open University Email: [email protected] Abstract Forming a coalition involves compromise, so a prime minister heading up a coalition government, even one as predominant a party leader as Cameron, should not be as powerful as a prime minister leading a single party government. Cameron has still to work with and through ministers from his own party, but has also to work with and through Liberal Democrat ministers; not least the Liberal Democrat leader Nick Clegg. The relationship between the prime minister and his deputy is unchartered territory for recent academic study of the British prime minister. This article explores how Cameron and Clegg operate within both Whitehall and Westminster: the cabinet arrangements; the prime minister’s patronage, advisory resources and more informal mechanisms. -

Connecting Ontological (In)Securities and Generation Through the Everyday and Emotional Geopolitics of Falkland Islanders

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Newcastle University E-Prints Benwell MC. Connecting ontological (in)securities and generation through the everyday and emotional geopolitics of Falkland Islanders. Social & Cultural Geography 2017 Copyright: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Social & Cultural Geography on 13th February 2017 available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1290819 Date deposited: 21/02/2017 Embargo release date: 13 February 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Connecting ontological (in)securities and generation through the everyday and emotional geopolitics of Falkland Islanders Matthew C. Benwell School of Geography, Politics and Sociology, Newcastle University, Daysh Building, Newcastle NE1 7RU, UK Abstract: Debates about the security of British Overseas Territories (OTs) like the Falkland Islands are typically framed through the discourses of formal and practical geopolitics in ways that overlook the perspectives of their citizens. This paper focuses on the voices of two generations of citizens from the Falkland Islands, born before and after the 1982 war, to show how they perceive geopolitics and (in)security in different ways. It uses these empirical insights to show how theorisations of ontological (in)security might become more sensitive to the lived experiences of diverse generational groups within states and OTs like the Falklands. The paper reflects on the complex experiences of citizens living in a postcolonial OT that still relies heavily on the UK government and electorate for assurances of security, in the face of diplomatic pressure from Argentina. -

Imperial Nostalgia: Victorian Values, History and Teenage Fiction in Britain

RONALD PAUL Imperial Nostalgia: Victorian Values, History and Teenage Fiction in Britain In his pamphlet, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, on the seizure of French government power in 1851 by Napoleon’s grandson, Louis, Karl Marx makes the following famous comment about the way in which political leaders often dress up their own ideological motives and actions in the guise of the past in order to give them greater historical legitimacy: The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. And just when they seem engaged in revolutionizing themselves and things, in creating something that has never yet existed, precisely in such periods of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service and borrow from them names, bat- tle-cries, and costumes in order to present the new scene of world history in this time-honoured disguise and this borrowed language.1 One historically contentious term that has been recycled in recent years in the public debate in Britain is that of “Victorian values”. For most of the 20th century, the word “Victorian” was associated with negative connotations of hypercritical morality, brutal industrial exploitation and colonial oppression. However, it was Mrs Thatcher who first gave the word a more positive political spin in the 1980s with her unabashed celebration of Victorian laissez-faire capitalism and patriotic fervour. This piece of historical obfuscation was aimed at disguising the grim reality of her neoliberal policies of economic privatisation, anti-trade union legislation, cut backs in the so-called “Nanny” Welfare State and the gunboat diplomacy of the Falklands War. -

The Sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit Era

Island Studies Journal, 15(1), 2020, 151-168 The sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories in the Brexit era Maria Mut Bosque School of Law, Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Spain MINECO DER 2017-86138, Ministry of Economic Affairs & Digital Transformation, Spain Institute of Commonwealth Studies, University of London, UK [email protected] (corresponding author) Abstract: This paper focuses on an analysis of the sovereignty of two territorial entities that have unique relations with the United Kingdom: the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories (BOTs). Each of these entities includes very different territories, with different legal statuses and varying forms of self-administration and constitutional linkages with the UK. However, they also share similarities and challenges that enable an analysis of these territories as a complete set. The incomplete sovereignty of the Crown Dependencies and BOTs has entailed that all these territories (except Gibraltar) have not been allowed to participate in the 2016 Brexit referendum or in the withdrawal negotiations with the EU. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that Brexit is not an exceptional situation. In the future there will be more and more relevant international issues for these territories which will remain outside of their direct control, but will have a direct impact on them. Thus, if no adjustments are made to their statuses, these territories will have to keep trusting that the UK will be able to represent their interests at the same level as its own interests. Keywords: Brexit, British Overseas Territories (BOTs), constitutional status, Crown Dependencies, sovereignty https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.114 • Received June 2019, accepted March 2020 © 2020—Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

Variety Description Origin Approximate Ripening Uses

Approximate Variety Description Origin Ripening Uses Yellow Transparent Tart, crisp Imported from Russia by USDA in 1870s Early July All-purpose Lodi Tart, somewhat firm New York, Early 1900s. Montgomery x Transparent. Early July Baking, sauce Pristine Sweet-tart PRI (Purdue Rutgers Illinois) release, 1994. Mid-late July All-purpose Dandee Red Sweet-tart, semi-tender New Ohio variety. An improved PaulaRed type. Early August Eating, cooking Redfree Mildly tart and crunchy PRI release, 1981. Early-mid August Eating Sansa Sweet, crunchy, juicy Japan, 1988. Akane x Gala. Mid August Eating Ginger Gold G. Delicious type, tangier G Delicious seedling found in Virginia, late 1960s. Mid August All-purpose Zestar! Sweet-tart, crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1999. State Fair x MN 1691. Mid August Eating, cooking St Edmund's Pippin Juicy, crisp, rich flavor From Bury St Edmunds, 1870. Mid August Eating, cider Chenango Strawberry Mildly tart, berry flavors 1850s, Chenango County, NY Mid August Eating, cooking Summer Rambo Juicy, tart, aromatic 16th century, Rambure, France. Mid-late August Eating, sauce Honeycrisp Sweet, very crunchy, juicy U Minn, 1991. Unknown parentage. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Burgundy Tart, crisp 1974, from NY state Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Blondee Sweet, crunchy, juicy New Ohio apple. Related to Gala. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Gala Sweet, crisp New Zealand, 1934. Golden Delicious x Cox Orange. Late Aug.-early Sept. Eating Swiss Gourmet Sweet-tart, juicy Switzerland. Golden x Idared. Late Aug.-early Sept. All-purpose Golden Supreme Sweet, Golden Delcious type Idaho, 1960. Golden Delicious seedling Early September Eating, cooking Pink Pearl Sweet-tart, bright pink flesh California, 1944, developed from Surprise Early September All-purpose Autumn Crisp Juicy, slow to brown Golden Delicious x Monroe. -

British Overseas Territories Law

British Overseas Territories Law Second Edition Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson HART PUBLISHING Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Kemp House , Chawley Park, Cumnor Hill, Oxford , OX2 9PH , UK HART PUBLISHING, the Hart/Stag logo, BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2018 First edition published in 2011 Copyright © Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson , 2018 Ian Hendry and Susan Dickson have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identifi ed as Authors of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. While every care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of this work, no responsibility for loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of any statement in it can be accepted by the authors, editors or publishers. All UK Government legislation and other public sector information used in the work is Crown Copyright © . All House of Lords and House of Commons information used in the work is Parliamentary Copyright © . This information is reused under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 ( http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3 ) except where otherwise stated. All Eur-lex material used in the work is © European Union, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/ , 1998–2018. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Video Preview

“People should know just how evil war can be. It is all well and good talking about the glory, but a lot of people get killed.” —Ken Wilkinson, Battle of Britain Spitfire Pilot, Royal Air Force Table of Contents Click the section title to jump to it. Click any blue or purple head to return: Video Preview Video Voices Connect the Video to Science and Engineering Design Explore the Video Explore and Challenge Identify the Challenge Investigate, Compare, and Revise Pushing the Envelope Build Science Literacy through Reading and Writing Summary Activity Next Generation Science Standards Common Core State Standards for ELA & Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects Assessment Rubric For Inquiry Investigation Video Preview "The Spitfire" is one of 20 short videos in the series Chronicles of Courage: Stories of Wartime and Innovation. At the start of World War II, the Battle of Britain erupted, and cities across England were Germany’s targets. The Royal Air Force (RAF) relied on one of their most beloved planes—the Supermarine Spitfire—and the brand-new radar technology to defend their homeland against Hitler and his attacking military. Time Video Content 0:00–0:16 Series opening 0:17–1:22 Why the Battle of Britain matters 1:23–1:44 One of The Few 1:45–2:57 The nimble Supermarine Spitfire 2:58 –4:04 The British could sniff out German aircraft 4:05–5:28 How Radio Detection and Ranging works 5:29–6:02 A victorious turning point 6:03–6:18 Closing credits Chronicles of Courage: Stories of Wartime and Innovation “The Spitfire” 1 Video Voices—The Experts Tell the Story By interviewing people who have demonstrated courage in the face of extraordinary events, the Chronicles of Courage series keeps history alive for current generations to explore. -

Benwell MC, Pinkerton A. Brexit and the British Overseas Territories: Changing Perspectives on Security

Benwell MC, Pinkerton A. Brexit and the British Overseas Territories: Changing Perspectives on Security. RUSI Journal 2016, 161(4), 8-14. Copyright: This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in RUSI Journal on 29/09/2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03071847.2016.1224489 Date deposited: 01/09/2016 Embargo release date: 29 March 2018 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Brexit and the British Overseas Territories: Changing perspectives on security Matthew C. Benwell and Alasdair Pinkerton On 23 June 2016 citizens of the United Kingdom (and residents of the UK Overseas Territory of Gibraltar) voted in a referendum to leave the European Union. While the exact modes and timings of this exit remain unclear, the campaign was characterised by increasingly heated debate and sharply contrasting visions for Britain and its relationship with the wider world in the twenty-first century. A coterie of international politicians and world leaders waded into the debate, as a reminder of both the global interest in the referendum campaign and the potential international implications of the UK’s decision – not least of all within the Overseas Territories (OTs) of the United Kingdom. Matthew Benwell and Alasdair Pinkerton argue that the UK’s 2016 EU referendum campaign and the political and economic evaluations that it has invited have exposed a shifting relationship between the UK and its OTs and demonstrate the role played by the EU in fostering their political, economic and regional security – a perspective often ignored by the OT’s so called ‘friends’ and supporters. -

Political Capture and Economic Inequality

178 OXFAM BRIEFING PAPER 20 JANUARY 2014 Housing for the wealthier middle classes rises above the insecure housing of a slum community in Lucknow, India. Photo: Tom Pietrasik/Oxfam WORKING FOR THE FEW Political capture and economic inequality Economic inequality is rapidly increasing in the majority of countries. The wealth of the world is divided in two: almost half going to the richest one percent; the other half to the remaining 99 percent. The World Economic Forum has identified this as a major risk to human progress. Extreme economic inequality and political capture are too often interdependent. Left unchecked, political institutions become undermined and governments overwhelmingly serve the interests of economic elites to the detriment of ordinary people. Extreme inequality is not inevitable, and it can and must be reversed quickly. www.oxfam.org SUMMARY In November 2013, the World Economic Forum released its ‘Outlook on the Global Agenda 2014’, in which it ranked widening income disparities as the second greatest worldwide risk in the coming 12 to 18 months. Based on those surveyed, inequality is ‘impacting social stability within countries and threatening security on a global scale.’ Oxfam shares its analysis, and wants to see the 2014 World Economic Forum make the commitments needed to counter the growing tide of inequality. Some economic inequality is essential to drive growth and progress, rewarding those with talent, hard earned skills, and the ambition to innovate and take entrepreneurial risks. However, the extreme levels of wealth concentration occurring today threaten to exclude hundreds of millions of people from realizing the benefits of their talents and hard work.