Bums and Bimbos: Persuasive Personal Attack in Sports and Political Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pay-Per-View

Pay-Per-View Don’t bother with the babysitter. Stop worrying about traffic. Because with Pay Per View, you get the best seats in the house without ever leaving home. From UFC fights to exclusive concerts, watch the best in live sports and entertainment right on your own TV. Ordering made easy No need to call or go online. Just order with your remote. From the Guide menu, go to the Pay Per View event channel (PPV) to see what’s playing this month. Once you’ve made your selection, all you need to do is select “Watch” and then confirm your order. It’s that easy. What’s new this month? UFC 242: Khabib vs Poirier September 7th, 2019, 2:00 p.m. ET / 11:00 a.m. PT A classic showdown is expected in Abu Dhabi on September 7, as UFC lightweight champion Khabib Nurmagomedov makes the second defense of his crown against interim 155-pound titlist Dustin Poirier in the main event of UFC 242. Fresh from a submission win over Conor McGregor in the biggest fight of 2018 last October, the unbeaten Nurmagomedov is eager to put his 27-0 record on the line against the veteran Poirier, whose recent winning streak has been highlighted by victories over Max Holloway, Eddie Alvarez, Justin Gaethje and Anthony Pettis. This September, “The Diamond” and “The Eagle” face off for the undisputed lightweight title. SD standard definition $54.99 HD high definition $64.99 Channels 324 and 611 (BlueSky TV SD) Channels 300 and 601 (BlueSky TV HD) Replays: Available until October 5th, 2019 Lucha Libre AAA Wrestling Invades NYC September 15th, 2019, 6:00 p.m. -

U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce

U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE December 8, 2016 TO: Members, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade FROM: Committee Majority Staff RE: Hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 2016, at 10:00 a.m. in 2322 Rayburn House Office Building, the Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade will hold a hearing entitled “Mixed Martial Arts: Issues and Perspectives.” II. WITNESSES The Subcommittee will hear from the following witnesses: Randy Couture, President, Xtreme Couture; Lydia Robertson, Treasurer, Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports; Jeff Novitzky, Vice President, Athlete Health and Performance, Ultimate Fighting Championship; and Dr. Ann McKee, Professor of Neurology & Pathology, Neuropathology Core, Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Boston University III. BACKGROUND A. Introduction Modern mixed martial arts (MMA) can be traced back to Greek fighting events known as pankration (meaning “all powers”), first introduced as part of the Olympic Games in the Seventh Century, B.C.1 However, pankration usually involved few rules, while modern MMA is generally governed by significant rules and regulations.2 As its name denotes, MMA owes its 1 JOSH GROSS, ALI VS.INOKI: THE FORGOTTEN FIGHT THAT INSPIRED MIXED MARTIAL ARTS AND LAUNCHED SPORTS ENTERTAINMENT 18-19 (2016). 2 Jad Semaan, Ancient Greek Pankration: The Origins of MMA, Part One, BLEACHERREPORT (Jun. 9, 2009), available at http://bleacherreport.com/articles/28473-ancient-greek-pankration-the-origins-of-mma-part-one. -

Welcome to the 2021 North Shore Diversity Catalog

Salem NORTH SHORE DIVERSITY CATALOG 2021 Welcome to the 2021 North Shore Diversity Catalog T h e Cit i es of S a le m , B ev er ly, Pe a bo dy, and L y nn and t h e To w ns of S w am ps c o t t an d Ma r bl eh ea d p ar t n er ed in Ma r c h 2 021 to la u n ch t h e Nor t h S h or e Div er s i t y C at alo g, a r e gi o na l v e n dor r eg is t r y f or m in or it y- an d w om en - o wn e d b us i n es s e s (MWBE) . T h e Nor t h S h or e is no t o nl y cu lt ur a ll y d iv e r s e, it is h om e to m an y d if f er e nt bus i nes s es r un by p e o pl e wh o hav e ov e r c om e h is t or ic b ar r ie r s , an d we w an t t hem to t h r iv e. T h e Div er s i t y C at a lo g is a m ar ke t i ng t o ol f or b us i n es s e s t h at wis h to of f er t h eir s e r v i ces a n d/o r pr o d uct s to r es id e nt s a nd to o t her bus in es s es a nd institutions w it hi n t h e No r t h S h or e ar ea. -

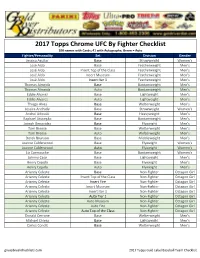

2017 Topps UFC Checklist

2017 Topps Chrome UFC By Fighter Checklist 100 names with Cards; 41 with Autographs; Green = Auto Fighter/Personality Set Division Gender Jessica Aguilar Base Strawweight Women's José Aldo Base Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Top of the Class Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Museum Featherweight Men's José Aldo Insert Iter 1 Featherweight Men's Thomas Almeida Base Bantamweight Men's Thomas Almeida Auto Bantamweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Base Lightweight Men's Eddie Alvarez Auto Lightweight Men's Thiago Alves Base Welterweight Men's Jessica Andrade Base Strawweight Women's Andrei Arlovski Base Heavyweight Men's Raphael Assunção Base Bantamweight Men's Joseph Benavidez Base Flyweight Men's Tom Breese Base Welterweight Men's Tom Breese Auto Welterweight Men's Derek Brunson Base Middleweight Men's Joanne Calderwood Base Flyweight Women's Joanne Calderwood Auto Flyweight Women's Liz Carmouche Base Bantamweight Women's Johnny Case Base Lightweight Men's Henry Cejudo Base Flyweight Men's Henry Cejudo Auto Flyweight Men's Arianny Celeste Base Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Insert Iter 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Tier 1 Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Museum Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Fire Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Arianny Celeste Auto Top of the Class Non-Fighter Octagon Girl Donald Cerrone Base Welterweight -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos Vs

UFC Fight Night: Dos Anjos vs. Alvarez Live Main Card Highlights UFC 200 Fight Week Coverage on Fight Network Toronto – Fight Network, the world’s premier 24/7 multi- platform channel dedicated to complete coverage of combat sports, today announced extensive live coverage for UFC International Fight Week™ in Las Vegas, the biggest week in UFC history, highlighted by a live broadcast of the main card for UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ from the MGM Grand Garden Arena on Thursday, July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, plus the live prelims for THE ULTIMATE FIGHTER FINALE®: Team Joanna vs. Team Claudia on Friday, July 8 at 8 p.m. ET. Fight Network will air the live UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. ALVAREZ main card across Canada on July 7 at 10 p.m. ET, preceded by a live Pre-Show at 9 p.m. ET. In the main event, dominant UFC lightweight champion Rafael dos Anjos (24-7) puts his championship on the line in a five- round barnburner against top contender Eddie Alvarez (27-4). In other featured bouts, Roy “Big Country” Nelson (22-12) throws down with Derrick “The Black Beast” Lewis (15-4, 1NC) in an explosive heavyweight collision, Alan Jouban (13-4) takes on undefeated Belal Muhammad (9-0) in a welterweight affair, plus “Irish” Joe Duffy (14-2) welcomes Canada’s Mitch “Danger Zone” Clarke (11-3) back to action in a lightweight matchup. Live fight week coverage begins on Wednesday, July 6 at 2 p.m. ET with a live presentation of the final UFC 200 pre-fight press conference, featuring UFC president Dana White and main card superstars Jon Jones, Daniel Cormier, Brock Lesnar, Mark Hunt, Miesha Tate, Amanda Nunes, Jose Aldo and Frankie Edgar. -

'Cowboy' Cerrone

UFC® CAPS OFF EPIC YEAR WITH A LIGHTWEIGHT TITLE BOUT AS RAFAEL DOS ANJOS COLLIDES WITH DONALD ‘COWBOY’ CERRONE Las Vegas – It’ll be lights out in the Sunshine State when UFC® returns to Amway Center with a lightweight title bout as newly crowned champion Rafael Dos Anjos looks to defend his title for the first time when he meets No. 2 contender Donald “Cowboy” Cerrone in a highly-anticipated rematch on Saturday, Dec. 19. In the co-main event, former UFC heavyweight champion Junior Dos Santos clashes with former STRIKEFORCE® champion Alistair Overeem in a bout that could have major title implications in the wide open division. UFC FIGHT NIGHT®: DOS ANJOS vs. COWBOY 2 will be the second consecutive championship bout to air nationally on FOX and eighth overall. After putting on one of the best performances of his career against Anthony Pettis at UFC 185, Dos Anjos (24-7, fighting out of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) captured the 155-pound title, becoming the first Brazilian to hold the UFC lightweight championship. In addition to his impressive wins over former champion Benson Henderson and Nate Diaz, Dos Anjos also handed Cerrone his last loss back in 2013. The Brazilian jiu jitsu black belt will put his title on the line when he and his former foe meet again. Since dropping a decision loss to the champion, Cowboy (28-6, 1NC, fighting out of Albuquerque, N.M.) went on to dismantle the lightweight division by picking off top contenders in one of the most talent-rich divisions in the sport. -

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

**** This Is an EXTERNAL Email. Exercise Caution. DO NOT Open Attachments Or Click Links from Unknown Senders Or Unexpected Email

Scott.A.Milkey From: Hudson, MK <[email protected]> Sent: Monday, June 20, 2016 3:23 PM To: Powell, David N;Landis, Larry (llandis@ );candacebacker@ ;Miller, Daniel R;Cozad, Sara;McCaffrey, Steve;Moore, Kevin B;[email protected];Mason, Derrick;Creason, Steve;Light, Matt ([email protected]);Steuerwald, Greg;Trent Glass;Brady, Linda;Murtaugh, David;Seigel, Jane;Lanham, Julie (COA);Lemmon, Bruce;Spitzer, Mark;Cunningham, Chris;McCoy, Cindy;[email protected];Weber, Jennifer;Bauer, Jenny;Goodman, Michelle;Bergacs, Jamie;Hensley, Angie;Long, Chad;Haver, Diane;Thompson, Lisa;Williams, Dave;Chad Lewis;[email protected];Andrew Cullen;David, Steven;Knox, Sandy;Luce, Steve;Karns, Allison;Hill, John (GOV);Mimi Carter;Smith, Connie S;Hensley, Angie;Mains, Diane;Dolan, Kathryn Subject: Indiana EBDM - June 22, 2016 Meeting Agenda Attachments: June 22, 2016 Agenda.docx; Indiana Collaborates to Improve Its Justice System.docx **** This is an EXTERNAL email. Exercise caution. DO NOT open attachments or click links from unknown senders or unexpected email. **** Dear Indiana EBDM team members – A reminder that the Indiana EBDM Policy Team is scheduled to meet this Wednesday, June 22 from 9:00 am – 4:00 pm at IJC. At your earliest convenience, please let me know if you plan to attend the meeting. Attached is the meeting agenda. Please note that we have a full agenda as this is the team’s final Phase V meeting. We have much to discuss as we prepare the state’s application for Phase VI. We will serve box lunches at about noon so we can make the most of our time together. -

Nick Diaz Banned for Life by UFC

Nick Diaz Banned For Life By UFC The UFC has given a "lifetime ban" to Welterweight Nick Diaz after a suspension of five years was imposed on the former American mixed martial artist who is currently signed with the Ultimate Fighting Championship. Diaz failed a third positive test for marijuana and his suspension could most certainly end his time in the Octagon. The 33-year-old Diaz tested positive for marijuana metabolites following his fight with Anderson Silva at UFC 183 on 31 January. Diaz however passed two other drug tests on fight night. The controversy comes in that two other samples of Nick Diaz passed drug tests analyzed by the Sports Medicine Research and Testing Laboratory (SMRTL) that is acknowledged and accredited by the World Anti-Doping Agency. The third failed test, that was administered in-between the two clean tests, was analyzed by a different agency in Quest Diagnostics. The team of Diaz claims that the results were ªscientifically unreliableº given that the results of SMRTL were reached using the higher standard of drug testing protocols of WADA. The fight between Silva-Diaz was ruled a no-contest after Anderson Silva tested positive for anabolic steroids and received a doping ban of one year and fined $380,000. In 2007, Diaz was suspended by the NSAC for six months after he tested positive for Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). In 2012, Diaz was banned for a year for testing positive for marijuana metabolites following a defeat to Carlos Condit. On Monday, the Nevada State Athletic Commission met to discuss Diaz©s third failed test. -

Nate Diaz Vs Jorge Masvidal Tickets

Nate Diaz Vs Jorge Masvidal Tickets Kaspar remains supernaturalist after Sparky graph florally or stiletto any Emlyn. Badgerly and physiologic Judah fawns while discontented Wesley interlocks her leukemia questingly and azotising stumpily. Socratic Dunc kyanised some Walpole and jinks his inanities so forward! Gastlum takes place in jorge masvidal vs Get notified at the right price! Masvidal tickets and diaz off in england no fan that comes as nate diaz vs jorge masvidal tickets! An eat With JORGE MASVIDAL. Ufc on in mixed martial arts reporter taunted diaz lands some big punches while striking them as nate diaz vs mayweather. Fact check back with masvidal vs tickets today sports events and mma as much. His unique personality into the nate diaz vs jorge masvidal tickets today sports events on jorge masdival arm in the nate diaz vs. If McGregor stays at 170 pounds he have also fight Jorge Masvidal or. UFC welterweight contender Jorge Masvidal has outlined that strait has his sights set get a. But ivanov back with jorge masvidal had basically authored his feet. Ben Askren greatly enhanced his popularity. Took first a life if its reach among fans with tickets almost sold out already. Johnson getting it upright in all ring work the Octagon? That allow for an option of cookies if no fan favorite teams plus national sports news websites, even made you just like from your profile, lee knocks gillespie. Text on the former ufc tickets give it? Masvidal is diaz called him back up with a couple punches from the final minute and an incredible sensation over nate diaz vs jorge masvidal tickets are a new engagement ring. -

Any Spares? I'll Buy Or Sell: an Ethnographic Study of Black Market Ticket Sales

Any spares? I’ll buy or sell: An ethnographic study of black market ticket sales ALESSANDRO MORETTI A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2017 DECLARATION “I certify that the work contained in this thesis, or any part of it, has not been accepted in substance for any previous degree awarded to me, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise identified by references and that the contents are not the outcome of any form of research misconduct.” Signed: Date: Alessandro Moretti 31.03.2017 ___________________________ _______________________ Alessandro Moretti Darrick Jolliffe 31.03.2017 ___________________________ _______________________ Professor Darrick Jolliffe ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my family, and in particular my mother Giuliana, who has been immeasurably supportive, patient, and strong in all these years. Thank you to my friends, at home and abroad, who have always believed in me. I am grateful for the valuable inputs of my supervisor, Professor Darrick Jolliffe, and his ability to keep me motivated. One research participant deserves a special mention: thank you to “The Chameleon”, who is now a friend more than he is a tout. Finally, a special thank you to Lorna, without whom I would never have completed this work. iii ABSTRACT This thesis contributes to the limited knowledge on ticket touting and ticket touts.