COMPLAINT 25 V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEBRASKA WRESTLING Weekly Notes: Tuesday, Feb

NEBRASKA WRESTLING Weekly Notes: Tuesday, Feb. 27, 2007 2006-07 Schedule Date Meet/Match Time/Score This Week in Husker Wrestling Nov. 11 Cowboy Open ! NTS Nov. 18 Kaufman-Brand Open @ NTS Conference Championships: Nov. 24 at Virginia Tech W, 34-9 No. 23/19 Nebraska (10-7-1) at 2007 Big 12 Championships Nov. 25 at Maryland W, 27-12 Hearnes Center•Columbia, Mo.•Saturday, March 3 Dec. 1-2 Las Vegas Invitational # 4th Last Year: Third Place, 52 pts, 9 NCAA qualifiers, one champion (Padden-197) Dec. 9 South Dakota State W, 32-9 TV: Tape-Delayed on FSN (channel 37 in Lincoln), Sunday, March 11, 12:30 p.m. Dec. 9 Northern Colorado W, 34-9 Dec. 16 Wyoming $ W, 34-10 Huskers Compete for Conference Title Dec. 16 Nebraska-Kearney $ W, 30-18 The 19th-ranked Nebraska wrestling team will aim for the program’s seventh conference championship Jan. 5 Oregon State L, 15-21 at the 2007 Big 12 Championships at the Hearnes Center in Columbia, Mo. Thirty-eight wrestlers will Jan. 13-14 National Duals % qualify for the NCAA Championships, including the top-three finishers in each weight class and eight Jan. 13 vs. Hofstra L, 6-32 wild-card selections. Jan. 13 vs. Michigan W, 23-13 Last year, 197-pound Big 12 champion B.J. Padden led the way as nine Husker wrestlers earned bids Jan. 13 vs. Iowa L, 5-30 to nationals from the Big 12 Championships. Along with Padden, 174-pound wrestler Jacob Klein reached Jan. 20 Iowa State L, 12-25 the finals, while Paul Donahoe (125), Patrick Aleksanyan (133), Dominick Moyer (141), Robert Sanders Jan. -

Arbeiten in Der Games- Branche

Arbeiten in der Games- Branche Kreativität trifft Technologie 4 Liebe Schüler, Studierende, Eltern und kreative Köpfe, 14 folgende Frage höre und lese ich immer wieder: „Wie werde ich Spiele- Entwickler/in und was muss ich dafür mitbringen?“ Das ist auf die Schnelle gar nicht so leicht zu beantworten. Das Arbeiten in der Games-Branche ist unglaublich vielfältig und genauso zahl- reich sind auch die Wege, die dahinführen. Ich hoffe, dieser Guide wird Euch als Starter-Kit helfen, eine erfolgreiche Karriere in der deutschen Games-Branche zu beginnen. Die folgenden Seiten geben 40 eine Übersicht zu den Einstiegs- und Ausbildungsmöglichkeiten, den unterschiedlichen Berufsbildern und all den Dingen, die die Games- Branche so besonders (großartig) machen. Spiele-Entwicklung ist ein kreativer Prozess an der Schnittstelle von Kultur, Technologie und Unterhaltung. Deshalb sind viele unterschiedliche Talente gefragt und mit Sicherheit besitzt Ihr einige davon! Games werden von Auto- 46 ren und Game-Designern erdacht, ihre grundlegenden Systeme von Programmierern entwickelt und ihre Welten von Grafik-, Animations- und Sound-Designern zum Leben erweckt. Darüber hinaus werden · 4 Spielemarkt: Von Bits & Bytes · 14 Berufsbilder der Spielebranche neben dem klassischen Marketing- oder Sales-Manager Berufe wie zur Hochtechnologie 16 Game Design der Community-Manager immer wichtiger, denn er steht in direktem Kontakt mit den Spielern. Für einige Berufe gibt es bereits duale Aus- 12 Arbeitsmarkt 18 Grafikdesign bildungsangebote, für andere, besonders im kreativen Bereich, ist ein 40 Frauen in der Games-Branche 20 Level/Content Design · Studium mit Games-Bezug die beste Voraussetzung. Darüber hinaus 42 Nicht alle entwickeln ein Spiel: 22 Writer/Storyteller gilt: Kommt zu „jobs & karriere“ auf der gamescom und zu einem Andere Berufe der Games-Branche 24 Game Producer „Tag der offenen Tür“, wie ihn viele Hochschulen anbieten, und stellt 44 Ein Ziel, viele Wege – Tipps der 26 Programmierer dort Eure Fragen. -

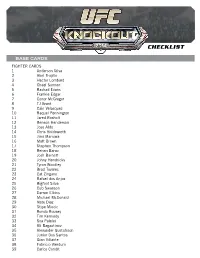

2014 Topps UFC Knockout Checklist

CHECKLIST BASE CARDS FIGHTER CARDS 1 Anderson Silva 2 Abel Trujillo 3 Hector Lombard 4 Chael Sonnen 5 Rashad Evans 6 Frankie Edgar 7 Conor McGregor 8 TJ Grant 9 Cain Velasquez 10 Raquel Pennington 11 Jared Rosholt 12 Benson Henderson 13 Jose Aldo 14 Chris Holdsworth 15 Jimi Manuwa 16 Matt Brown 17 Stephen Thompson 18 Renan Barao 19 Josh Barnett 20 Johny Hendricks 21 Tyron Woodley 22 Brad Tavares 23 Cat Zingano 24 Rafael dos Anjos 25 Bigfoot Silva 26 Cub Swanson 27 Darren Elkins 28 Michael McDonald 29 Nate Diaz 30 Stipe Miocic 31 Ronda Rousey 32 Tim Kennedy 33 Soa Palelei 34 Ali Bagautinov 35 Alexander Gustafsson 36 Junior Dos Santos 37 Gian Villante 38 Fabricio Werdum 39 Carlos Condit CHECKLIST 40 Brandon Thatch 41 Eddie Wineland 42 Pat Healy 43 Roy Nelson 44 Myles Jury 45 Chad Mendes 46 Nik Lentz 47 Dustin Poirier 48 Travis Browne 49 Glover Teixeira 50 James Te Huna 51 Jon Jones 52 Scott Jorgensen 53 Santiago Ponzinibbio 54 Ian McCall 55 George Roop 56 Ricardo Lamas 57 Josh Thomson 58 Rory MacDonald 59 Edson Barboza 60 Matt Mitrione 61 Ronaldo Souza 62 Yoel Romero 63 Alexis Davis 64 Demetrious Johnson 65 Vitor Belfort 66 Liz Carmouche 67 Julianna Pena 68 Phil Davis 69 TJ Dillashaw 70 Sarah Kaufman 71 Mark Munoz 72 Miesha Tate 73 Jessica Eye 74 Steven Siler 75 Ovince Saint Preux 76 Jake Shields 77 Chris Weidman 78 Robbie Lawler 79 Khabib Nurmagomedov 80 Frank Mir 81 Jake Ellenberger CHECKLIST 82 Anthony Pettis 83 Erik Perez 84 Dan Henderson 85 Shogun Rua 86 John Makdessi 87 Sergio Pettis 88 Urijah Faber 89 Lyoto Machida 90 Demian Maia -

Absolute Championship Berkut History+Geography

ABSOLUTE CHAMPIONSHIP BERKUT HISTORY+GEOGRAPHY The MMA league Absolute Championship Berkut was founded in early 2014 on the basis of the fight club “Berkut”. The first tournament was held by the organization on March 2 and it marked the beginning of Grand Prix in two weight divisions. In less than two years the ACB company was able to become one of three largest Russian MMA organizations. Also, a reputable independent website fightmatrix.com named ACB the number 1 promotion in our country. 1 GEOGRAPHY BELGIUM The geography of the tournaments covered GEORGIA more than 10 Russian cities, as well as Tajikistan, Poland, Georgia and Scotland. 50 MMA tournaments, 8 kickboxing ones HOLLAND POLAND and 3 Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu tournaments will be held by the promotion by the end of 2016 ROMANIA TAJIKISTAN SCOTLAND RUSSIA 2 OUR CLIENT’S PORTRAIT AGE • 18-55 YEARS OLD TARGET AGE • 23-29 YEARS OLD 9\1 • MEN\WOMEN Income: average and above average 3 TV BROADCAST Tournaments are broadcast on TV channels Match!Fighter and BoxTV as well as online. Average audience coverage per tournament: - On TV - 500,000 viewers; - Online - 150,000 viewers. 4 Media coverage Interviews with participants of the tournament are regularly published in newspapers and on websites of leading Russian media: SPORTBOX.RU, R- SPORT.RU, CHAMPIONAT.COM, MMABOXING.RU, ALLFIGHT.RU , etc. Foremost radio stations, Our Radio, Rock FM, Sport FM, etc. also broadcast the interviews. 5 INFORMATION SUPPORT Our promotion is also already well known outside Russia. Tournament broadcasts and the main news of the league regularly appear on major international websites: 6 Social networks coverage THOUSAND 400 SUBSCRIBERS 4,63 MILLION VIEWS 7 COMPANY MANAGEMENT The founder of the ACB league is one of the most respected citizens of the Chechen Republic – Mairbek Khasiev. -

2005 75Th NCAA Wrestling Tournament 3/17/2005 to 3/19/2005

75th NCAA Wrestling Tournament 2005 3/17/2005 to 3/19/2005 at St. Louis Team Champion Oklahoma State - 153 Points Outstanding Wrestler: Greg Jones - West Virginia Gorriaran Award: Evan Sola - North Carolina Top Ten Team Scores Number of Individual Champs in parentheses. 1 Oklahoma State 153 (5) 6 Illinois 70.5 2 Michigan 83 (1) 7 Iowa 66 3 Oklahoma 77.5 (1) 8 Lehigh 60 4 Cornell 76.5 (1) 9 Indiana 58.5 (1) 5 Minnesota 72.5 10 Iowa State 57 Champions and Place Winners Wrestler's seed in brackets, [US] indicates unseeeded. 1251st: Joe Dubuque [5] - Indiana (2-0) 2nd: Kyle Ott [3] - Illinois 3rd: Sam Hazewinkel [1] - Oklahoma (6-3) 4th: Nick Simmons [2] - Michigan State 5th: Efren Ceballos [6] - Cal State-Bakersfield (3-2) 6th: Vic Moreno [4] - Cal Poly-SLO 7th: Bobbe Lowe [8] - Minnesota (7-3) 8th: Coleman Scott [9] - Oklahoma State 1331st: Travis Lee [1] - Cornell (6-3) 2nd: Shawn Bunch [2] - Edinboro 3rd: Tom Clum [5] - Wisconsin (2-1) 4th: Mack Reiter [3] - Minnesota 5th: Matt Sanchez [10] - Cal State-Bakersfield (10-5) 6th: Evan Sola [11] - North Carolina 7th: Mark Jayne [4] - Illinois (5-3) 8th: Drew Headlee [US] - Pittsburgh 1411st: Teyon Ware [2] - Oklahoma (3-2) 2nd: Nate Gallick [1] - Iowa State 3rd: Cory Cooperman [4] - Lehigh (10-1) 4th: Daniel Frishkorn [7] - Oklahoma State 5th: Michael Keefe [11] - Tennessee-Chattanooga (Med FFT) 6th: Andy Simmons [5] - Michigan State 7th: Casio Pero [12] - Illinois (6-5 TB1) 8th: Josh Churella [3] - Michigan 1491st: Zack Esposito [1] - Oklahoma State (5-2) 2nd: Phillip Simpson [2] - Army 3rd: -

Cultivating Identity and the Music of Ultimate Fighting

CULIVATING IDENTITY AND THE MUSIC OF ULTIMATE FIGHTING Luke R Davis A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Megan Rancier, Advisor Kara Attrep © 2012 Luke R Davis All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Megan Rancier, Advisor In this project, I studied the music used in Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) events and connect it to greater themes and aspects of social study. By examining the events of the UFC and how music is used, I focussed primarily on three issues that create a multi-layered understanding of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) fighters and the cultivation of identity. First, I examined ideas of identity formation and cultivation. Since each fighter in UFC events enters his fight to a specific, and self-chosen, musical piece, different aspects of identity including race, political views, gender ideologies, and class are outwardly projected to fans and other fighters with the choice of entrance music. This type of musical representation of identity has been discussed (although not always in relation to sports) in works by past scholars (Kun, 2005; Hamera, 2005; Garrett, 2008; Burton, 2010; Mcleod, 2011). Second, after establishing a deeper sense of socio-cultural fighter identity through entrance music, this project examined ideas of nationalism within the UFC. Although traces of nationalism fall within the purview of entrance music and identity, the UFC aids in the nationalistic representations of their fighters by utilizing different tactics of marketing and fighter branding. Lastly, this project built upon the above- mentioned issues of identity and nationality to appropriately discuss aspects of how the UFC attempts to depict fighter character to create a “good vs. -

Crash- Amundo

Stress Free - The Sentinel Sedation Dentistry George Blashford, DMD tvweek 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com January 19 - 25, 2019 Don Cheadle and Andrew Crash- Rannells star in “Black Monday” amundo COVER STORY .................................................................................................................2 VIDEO RELEASES .............................................................................................................9 CROSSWORD ..................................................................................................................3 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ....................................................................................................12 SPORTS.........................................................................................................................4 SUDOKU .....................................................................................................................13 FEATURE STORY ...............................................................................................................5 WORD SEARCH / CABLE GUIDE .........................................................................................19 READY FOR A LIFT? Facelift | Neck Lift | Brow Lift | Eyelid Lift | Fractional Skin Resurfacing PicoSure® Skin Treatments | Volumizers | Botox® Surgical and non-surgical options to achieve natural and desired results! Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Deborah M. Farrell, M.D. www.Since1853.com MODEL Fredricksen Outpatient Center, 630 -

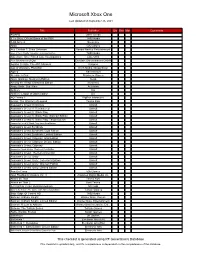

Microsoft Xbox One

Microsoft Xbox One Last Updated on September 26, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments #IDARB Other Ocean 8 To Glory: Official Game of the PBR THQ Nordic 8-Bit Armies Soedesco Abzû 505 Games Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown Bandai Namco Entertainment Aces of the Luftwaffe: Squadron - Extended Edition THQ Nordic Adventure Time: Finn & Jake Investigations Little Orbit Aer: Memories of Old Daedalic Entertainment GmbH Agatha Christie: The ABC Murders Kalypso Age of Wonders: Planetfall Koch Media / Deep Silver Agony Ravenscourt Alekhine's Gun Maximum Games Alien: Isolation: Nostromo Edition Sega Among the Sleep: Enhanced Edition Soedesco Angry Birds: Star Wars Activision Anthem EA Anthem: Legion of Dawn Edition EA AO Tennis 2 BigBen Interactive Arslan: The Warriors of Legend Tecmo Koei Assassin's Creed Chronicles Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III: Remastered Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: Target Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag: GameStop Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed Syndicate: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey: Deluxe Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Odyssey Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Origins: Steelbook Gold Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: The Ezio Collection Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Collector's Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Walmart Edition Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Unity: Limited Edition Ubisoft Assetto Corsa 505 Games Atari Flashback Classics Vol. 3 AtGames Digital Media Inc. -

The Licking Valley Courier Thursday, March 27, 2008 Page One-B

TheThe LickingLicking ValleyValley CourierCourier Morgan County’s HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER Speaking Of and For Morgan, the Bluegrass County of the Mountains Since 1910 (USPS 312-040) Morgan County Courthouse - Built 1907 Per $22.50 Year In County Volume 97 — No. 32 WEST LIBERTY, KENTUCKY 41472, THURSDAY, MARCH 27, 2008 ¢ $25.00 Year In Kentucky 50 Copy $27.00 Year Outside Kentucky City Council Court adopts tax again tables amendment package, avoids to dog law By Miranda Cantrell James takeover by state The West Liberty City Coun- cil at its regular March 24 meet- Measures pass 3-2 with one abstention ing voted again to table for fur- Ordinances imposing a one county’s long-standing budget ther discussion a proposed half of one percent county pay- problems. amendment of the city’s dog law roll tax and increasing the The new taxes are expected to ordinance to impose higher fines county’s insurance premium tax generate approximately for violations. by 2.5 percent — from 2.5 to 4.5 $575,000 annually, which will Mayor Bob Nickell expressed percent — got their second read- allow the magistrates to escape a desire to repeal and update the ings Monday and were adopted incurring a deficit in the county’s current ordinance, which requires by the fiscal court on a vote of 3 current budget and allow work to police officers to impound stray to 2 with one abstention. begin on preparation of a new dogs. The two revenue-enhancing budget for 2008-2009. “This is a liability issue,” measures, which received their Judge Executive Tim Conley Nickell said. -

Hit Show Dana White's Contender Series

HIT SHOW DANA WHITE’S CONTENDER SERIES CONTINUES ITS FOURTH SEASON WITH EPISODE 7 AIRING LIVE TUESDAY FROM UFC APEX IN LAS VEGAS Las Vegas – The fourth season of the hit show Dana White’s Contender Series continues with Episode 7, featuring a lineup of rising athletes looking to make their dreams come true by impressing UFC President Dana White and earning a spot on the UFC roster. The seventh episode of season four takes place on Tuesday, September 15 at 8 p.m. ET / 5 p.m. PT, with all five bouts streaming exclusively on ESPN+ in the US. ESPN+ is available through the ESPN.com, ESPNPlus.com or the ESPN App on all major mobile and connected TV devices and platforms, including Amazon Fire, Apple, Android, Chromecast, PS4, Roku, Samsung Smart TVs, X Box One and more. Fans can sign up for $4.99 per month or $49.99 per year, with no contract required. To support your coverage, please find the download link to the season four sizzle reels here and here. In addition, please find the download link for the season four athlete feature here, which highlights some of the participating athletes, their backgrounds and what competing on Dana White’s Contender Series means to them. Season 4, Episode 7 – Confirmed Bouts: Middleweight Gregory Rodrigues vs. Jordan Williams Featherweight Muhammad Naimov vs. Collin Anglin Welterweight Korey Kuppe vs. Michael Lombardo Women’s featherweight Danyelle Wolf vs. Taneisha Tennant Featherweight Dinis Paiva vs. Kyle Driscoll Visit the UFC.com for information and additional content to support your UFC coverage. -

Bo Nickal Wins the Hodge! Date: April 1, 2019 at 12:34 PM To: Undisclosed-Recipients:;

From: Pat Donghia [email protected] Subject: Bo Nickal Wins the Hodge! Date: April 1, 2019 at 12:34 PM To: undisclosed-recipients:; Bo Nickal Wins the Hodge! Three-time NCAA Champion wins wrestling’s Heisman UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa.; April 1, 2019 – (Portion of release, including quotes, courtesy Bryan Van Kley, WIN Magazine) Penn State Nittany Lion wrestler Bo Nickal (Allen, Texas) has won the WIN Magazine/Culture House Dan Hodge Trophy, presented annually to the top collegiate wrestler in the nation by ASICS. The Hodge Trophy has been awarded since 1995. The three-time NCAA champion finished first in the voting, just ahead of teammate Jason Nolf (Yatesboro, Pa.). A Nittany Lion has now won the last three Hodge Trophy awards. Nickal joins former Nittany Lion greats Zain Retherford and David Taylor, who each claimed two Hodge Trophy honors, and former Lion stand-out Kerry McCoy, who won the honor in 1997, as Penn State recipients. In all, Penn State now has four different individuals who have won the honor six times. The Nittany Lion won his third NCAA championship on March 23, defeating Kollin Moore of Ohio State. The 5-1 finals victory at 197 pounds was Nickal’s 30th of an undefeated senior campaign that included 18 pins, three tech falls and six major decisions. In a year that featured four outstanding finalists for the award, known as “wrestling’s Heisman Trophy,” Nickal won the honor over a senior teammate Jason Nolf, also a three-time NCAA champ who had very similar stats as Nickal. The other two Hodge finalists were Rutgers’ senior Anthony Ashnault and Cornell sophomore two-time champ Yianni Diakomihalis, who won NCAA championships at 149 and 141 pounds, respectively. -

Brooks, UFC, Mars Giving Las Vegas Big Back-To- Back Weekends by Richard N

Brooks, UFC, Mars giving Las Vegas big back-to- back weekends By Richard N. Velotta Las Vegas Review-Journal July 8, 2021 - 11:14 pm Normally, there’s a tourism lull the week after a three-day weekend. But as everyone knows, 2021 is far from normal, and the weekend after the three-day Fourth of July holiday has the makings of a blockbuster for Las Vegas. Credit a supercluster of blockbuster entertainment coming up in the city this weekend. The UFC 264 event at T-Mobile Arena, featuring Conor McGregor-Dustin Poirier. Garth Brooks at Allegiant Stadium. Bruno Mars at Park MGM. On top of that, former President Donald Trump is planning to attend the big fight, UFC President Dana White confirmed Thursday. The Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority doesn’t have any historical data to calculate an estimate of how many people will venture to Las Vegas this weekend, but most observers think more than 300,000 people were in the city over the Fourth of July three-day holiday. Will 300,000 more be here this weekend? Testing transportation If nothing else, the existing transportation grid will be put to the test with three major events — the Garth Brooks concert, the UFC fights and Bruno Mars — occurring at venues within a half-mile of each other at right around the same time that night. But health officials have expressed concern that big crowds have the potential to create superspreader events. Nevada on Thursday reported 697 new coronavirus cases and two deaths as the state’s test positivity rate continued to climb.