Women's Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Mille Occhi

da un miliardo a un marajah. Così Julie decide di convincere la sorella 9-11 settembre 13-14 settembre a restituire il gioiello. Ovviamente la storia non è così liscia e nel finale Gli introvabili esploderà l’ambiguità della Baker» (Giusti). del cinema fantastico Anteprima della XV edizione di italiano I mille occhi 16-20 settembre «Come è ormai tradizione, anche quest’anno è il Fantafestival, alla Festival internazionale sua XXXVI edizione, a riaprire con un proprio programma, la stagio - del cinema e delle arti Lucio Fulci ne del Cinema Trevi, e lo fa con una selezione di rarità tratte dalla «La felice consuetudine di quest’anteprima al Cinema Trevi si rinnova poeta del macabro (e non solo) produzione di genere fantastico di alcuni registi italiani, “minori” ma per un’edizione “tonda” del festival, la quindicesima. Sempre più si trat - A trent’anni dalla morte di Lucio Fulci, allievo del Centro Sperimentale fondamentali per il genere fantastico, per il quale lavorarono inten - ta di un prolungamento del programma realizzato a Trieste, non quindi di Cinematografia e una delle personalità più complesse del mondo samente negli anni Sessanta e Settanta, in quel magico periodo in film da replicare quest’anno, ma piuttosto estensioni di edizioni passate dello spettacolo italiano, la Cineteca Nazionale non poteva non render - cui il fantastico che connotò tutto il cinema europeo. A Silvio Amadio, e future del festival, in un work in progress che trova nell’edizione 2016 gli omaggio, curando una rassegna e presentando la versione ampliata Paolo Heusch, Gino Mangini, Renato Polselli, Elio Scardamaglia, un assestamento necessariamente fluido e mai compiuto. -

978–0–230–30016–3 Copyrighted Material – 978–0–230–30016–3

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–30016–3 Introduction, selection and editorial matter © Louis Bayman and Sergio Rigoletto 2013 Individual chapters © Contributors 2013 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2013 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–30016–3 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

Lunedì 20 Gennaio Debutta "Cine34" Nuova Rete

GIOVEDì 16 GENNAIO 2020 Lunedì 20 gennaio 2020 debutta "CINE34", la nuova rete tematica Mediaset dedicata al cinema italiano in tutte le sue declinazioni. Un canale dal nome chiaro, semplice, che aiuta il telespettatore a Lunedì 20 gennaio debutta identificarlo alla posizione 34 del telecomando. "Cine34" nuova rete Mediaset La linea editoriale di "CINE34" vuole rappresentare l'intera produzione dedicata al cinema italiano italiana, senza alcun pregiudizio, passando dai migliori titoli d'autore a quelli di genere. Su "CINE34" troveranno spazio tutti gli stili: dal poliziottesco al kolossal Esordio con i capolavori restaurati di Federico storico, dalle comiche ai telefoni bianchi, dal neorealismo al trash, dal Fellini nel centenario dalla nascita: in prima melodramma al sexy, dal peplum al musicarello, dalla fantascienza allo serata "Amarcord" e "La Dolce Vita" spaghetti western, dal giallo all'horror. Sempre e solo all'italiana. "CINE34" attinge a una library di titoli estesa e completa (con 2.672 titoli, 446 inediti) a cui si aggiungono acquisti ad hoc. Il palinsesto, declinato in ANTONIO GALLUZZO appuntamenti verticali, proporrà anche alcune chicche: film usciti nelle sale, mai visti prima sul piccolo schermo. Tra i titoli delle prime settimane di "CINE34". [email protected] SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Poliziotteschi doc: La Polizia incrimina, la Legge assolve e MMM 83 - Missione Morte Molo 83 (eurospy in prima visione assoluta con Anna Maria Pierangeli, diretto da Sergio Bergonzelli, ex seminarista laureato in Filosofia). Western al debutto in TV: tra cui Bandidos (di Massimo Dallamano, che nel '45, a Piazzale Loreto, filmò il cadavere di Mussolini con la Petacci e gli altri gerarchi fucilati a Dongo), Black Killer (di Carlo Croccolo, con Klaus Kinski), ed evergreen quali Lo chiamavano Trinità, parodia dello Spaghetti Western. -

The Italianisation of Bollywood Cinema: Ad Hoc Films

The Italianisation of Bollywood Cinema: ad hoc films Abstract The relationship explored by this article is the one between Italy and popular Hindi cinema wherein the films of Bollywood have undergone a profound change in form and narrative structure absorbing, through a collage of images, traces of the Italian inheritance of its cinema. This phenomenon is studied as framed by Bergson’s theory of time and with the technique of collage and the textual dismemberment that Bollywood films undergoes while approaching the Italian screens. The analysis of how Bollywood cinema reaches Italy and the current use that the Italian entertainment industry makes of Bollywood texts (by adapting these texts for the national audience) is pivotal to understanding how, on the one hand Bollywood has been targeted for cultural and aesthetic changes, and on the other hand how the encounter of this industry with the European panorama has its own specificities. Through the analysis of one specific case study, the Ashutosh Gowariker’s Jodhaa Akbar, which function as example among other Bollywood films screened in Italy, it will be highlighted how the Bollywood films, when filtered by the Italian entertainment industry produces ad hoc films, which re-frame the globalization of this Indian industry. Bio Dr. Monia Acciari completed her PhD at the University of Manchester, UK. After her PhD, she has been a Teaching Fellow at Swansea University. Currently, she is an Honorary Research Associate within the Department of Languages Translation and Communication at the Swansea University, UK. Her research interests are in Popular Hindi cinema, Contemporary Indian Indi Films, Coproduction Italy-India, Film Festival Studies, Film and Emotions, Cinema and other Performing Arts, Screen Genre, Diasporic and Transnational Media, Entertainment in Places of War, and Qualitative Research Methods applied to Popular Culture. -

FORME E CULTURE DEL CINEMA ITALIANO Prof.Ssa Giulia Fanara Anno 2020/2021

FORME E CULTURE DEL CINEMA ITALIANO Prof.ssa Giulia Fanara Anno 2020/2021 LIBRO DI TESTO P. Sorcinelli, A. Varni, Il secolo dei giovani. Le nuove generazioni e la storia del Novecento, Donzelli, Roma 2004. DISPENSE EXCURSUS GENERALI 1. Anni Cinquanta: S. Venturini, Spettacolo e tecnica nelle coproduzioni degli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta, in G. Manzoli, G. Pescatore (a cura di), L’arte del risparmio: stile e tecnologia, Carocci, Roma 2005, pp. 68-77. 2. Anni Sessanta: S. Gundle, I comunisti italiani tra Hollywood e Mosca: la sfida della cultura di massa: 1943-1991, Giunti, Firenze 1995, pp. 235-301. 3. Anni Settanta: G. Pescatore, La cultura mediale tra consumo e partecipazione, “Bianco e Nero”, 572, 2012, pp. 11-19. 4. Divismo: C. Jandelli, Breve storia del divismo cinematografico, Marsilio, Venezia 2007, pp. 107-125. MELODRAMMA 5. F. Di Chiara, Generi e industria cinematografica in Italia. Il caso Titanus (1949-1964), Lindau, Torino 2013, pp. 95-128. 6. L. Cardone, Rosa oscuro. Modelli femminili nel mélo matarazziano, «Cinegrafie», 2007, pp. 41-53. NEOREALISMO ROSA 7. E. Capussotti, Gioventù perduta. Gli anni Cinquanta dei giovani e del cinema in Italia, Giunti, Firenze 2004, pp. 151-168, 194-204. MUSICARELLI 8. E. Capussotti, Gioventù perduta. Gli anni Cinquanta dei giovani e del cinema in Italia, Giunti, Firenze 2004, pp. 204-249, 255-261. 9. C. Bisoni, “Il problema più importante per noi/è di avere una ragazza di sera”. Percorsi della sessualità e identità di gender nel cinema musicale italiano degli anni Sessanta, “Cinergie”, 3, 5, pp. 70-82. 10. R. Catanese, Vespa, Lambretta e Geghegé. -

Formations of Indian Cinema in Dublin: a Participatory Researcher-Fan Ethnography

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2016-4 Formations of Indian Cinema in Dublin: A Participatory Researcher-Fan Ethnography Giovanna Rampazzo Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Rampazzo, G. (2016) Formation of Indian cinema in Dublin: a participatory researcher-fan ethnographyDoctoral Thesis. Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D7C010 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License Formations of Indian Cinema in Dublin: A Participatory Researcher-Fan Ethnography Giovanna Rampazzo, MPhil This Thesis is submitted to the Dublin Institute of Technology in Candidature for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2016 Centre for Transcultural Research and Media Practice School of Media College of Arts and Tourism Supervisors: Dr Alan Grossman Dr Anthony Haughey Dr Rashmi Sawhney Abstract This thesis explores emergent formations of Indian cinema in Dublin with a particular focus on globalising Bollywood film culture, offering a timely analysis of how Indian cinema circulates in the Irish capital in terms of consumption, exhibition, production and identity negotiation. The enhanced visibility of South Asian culture in the Irish context is testimony to on the one hand, the global expansion of Hindi cinema, and on the other, to the demographic expansion of the South Asian community in Ireland during the last decade. -

LA COMPILATION SOUNDTRACK NEL CINEMA SONORO ITALIANO a Cura Di Maurizio Corbella

E DEI MEDIA IN ITALIA IN MEDIA DEI E CINEMA DEL CULTURE E STORIE SCHERMI LA COMPILATION SOUNDTRACK NEL CINEMA SONORO ITALIANO a cura di Maurizio Corbella ANNATA IV NUMERO 7 gennaio giugno 2020 Schermi è pubblicata sotto Licenza Creative Commons SCHERMI STORIE E CULTURE DEL CINEMA E DEI MEDIA IN ITALIA LA COMPILATION SOUNDTRACK NEL CINEMA SONORO ITALIANO a cura di Maurizio Corbella ANNATA IV NUMERO 7 gennaio-giugno 2020 ISSN 2532-2486 SCHERMI 7 - 2020 Direzione | Editors Mariagrazia Fanchi (Università Cattolica di Milano) Giacomo Manzoli (Università di Bologna) Tomaso Subini (Università degli Studi di Milano) Comitato scientifico | Advisory Board Daniel Biltereyst (Ghent University) David Forgacs (New York University) Paolo Jedlowski (Università della Calabria) Daniele Menozzi (Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa) Pierre Sorlin (Université “Sorbonne Nouvelle” - Paris III) Daniela Treveri Gennari (Oxford Brookes University) Comitato redazionale | Editorial Staff Mauro Giori (Università degli Studi di Milano), caporedattore Luca Barra (Università di Bologna) Gianluca della Maggiore (Università Telematica Internazionale UniNettuno) Cristina Formenti (Università degli Studi di Milano) Damiano Garofalo (Sapienza Università di Roma) Dominic Holdaway (Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo) Dalila Missero (Oxford Brookes University) Paolo Noto (Università di Bologna) Maria Francesca Piredda (Università Cattolica di Milano) Redazione editoriale | Contacts Università degli Studi di Milano Dipartimento di Beni culturali e ambientali Via Noto, 6 -

New Perspectives on Italian Cinema of the Long 1960S Guest Editorial

Journal of Film Music 8.1–2 (2015) 5-12 ISSN (print) 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.37317 ISSN (online) 1758-860X Film Music Histories and Ethnographies: New Perspectives on Italian Cinema of the Long 1960s Guest Editorial ALESSANDRO CECCHI University of Pisa [email protected] MAURIZIO CORBELLA University of Milan [email protected] here is no doubt that the 1960s represent Two historical ruptures bookending the decade an exceptional period in Italian film history. characterize this period: the economic boom, TPeter Bondanella labeled the decade from also labeled the “economic miracle,” and the 1958 to 1968 “the Golden Age of Italian cinema, movement of 1968. The development of these two for in no other single period was its artistic quality, phenomena justifies our choice of the label “the its international prestige, or its economic strength long 1960s.” In the case of the economic miracle, so consistently high.”1 Indeed, as David Forgacs which is usually regarded as encompassing the years and Stephen Gundle put it, this was “the only 1958–1963,4 one could in fact consider it, as does time [. .] when [. .] a surge in Italian production Silvio Lanaro, “a quite tangible yet not clamorous was accompanied by a sharp decline in U.S. film acceleration of an expansive process that had started production and export.”2 At any rate, as Gian Piero in 1951–52.”5 Accordingly, Forgacs and Gundle Brunetta remarked, the films made in that period have explicitly challenged the idea of “a unique “were memorable for their quantity -

The Birth of Pop. the Soundscapes of the Sixties in Italian Cinema and Television

THE BIRTH OF POP. THE SOUNDSCAPES OF THE EARLY SIXTIES IN ITALIAN CINEMA AND TELEVISION Massimo Locatelli 1. INTRODUCTION In post-WWII Europe, film culture related in many different ways to a wide range of mod- ern cultural practices. It had the emerging pop music industry at its centre and this was revo- lutionizing the landscapes and soundscapes we live in. The aim of my contribution is to delve into these related practices, taking the Italian case as my focus. I will explore its crucial journey to mediatization from the Fifties to the Sixties and will argue that it offers an exemplary tra- jectory for its (apparently excessive) foregrounding of music and sounds both in national film culture and in the transnational mediascape. I will examine the well-known performer, Adriano Celentano, as my case study. Celentano debuted as the Italian rocker par excellence at the end of the Fifties, starting an impressive and unprecedented career in our national pop culture.1 As a singer, songwriter, comedian and actor (later also as a successful television host) he posited himself at the centre of the process of integration of the media industries that characterized the on-going modernization of Italy. Celentano is crucial in my view because he is part of the generation that configured Italy’s first basic encounter with pervasive modern lifestyles and media technologies. A conservative culture was nudged, because of this, towards change. 2. THE TUNING OF THE COUNTRY To begin, we need to define the economic and political context of the time, sketching its social and technological values. -

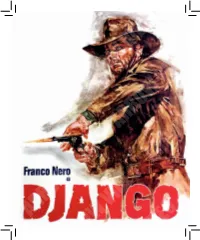

Django Sb Booklet Wate

ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 1 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 1 CONTENTS 4 Django: Cast and Crew 7 The D is Silent: A Legend is Born (2018) by Howard Hughes 14 Django: Contemporary Reviews compiled by Roberto Curti 16 Texas, Adios: Cast and Crew 19 Cut to the Action: The Films of Ferdinando Baldi (2018) by Howard Hughes 29 Texas, Adios: Contemporary Reviews compiled by Roberto Curti 30 About the Restorations ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO2 ARROW VIDEO 3 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO CREW Directed by Sergio Corbucci Produced by Manolo Bolognini and Sergio Corbucci 1966 Story and Screenplay by Sergio Corbucci and Bruno Corbucci Screenplay in collaboration with Piero Vivarelli and Franco Rossetti Director of Photography Enzo Barboni A.I.C. CAST Camera Operators Idelmo Simonelli, Gianni Bergamini and Gaetano Valle Assistant Cameraman Fernando Gallandt Franco Nero Django Assistant Director Ruggero Deodato Loredana Nusciak Maria Production Manager Bruno Frascà José Bódalo General Hugo Rodriguez Edited by Nino Baragli and Sergio Montanari Eduardo Fajardo Major Jackson Continuity Patrizia Zulini Ángel Álvarez Nathaniel, the saloonkeeper Fire Arms Remo De Angelis Gino Pernice (as Jimmy Douglas) Brother Jonathan Set Designer and Costumes Giancarlo Simi Remo De Angelis (as Erik Schippers) Ricardo, Rodriguez gang member Costumes Marcella De Marchis José Canalejas (as José Canalecas) Rodriguez gang member Set Decorator Francisco Ganet Simón Arriaga Miguel, Rodriguez gang member Make-up Mario Van Riel Rafael Albaicín Rodriguez gang member ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Hair Styles Grazia De’Rossi José Terrón Ringo Properties and Furniture Francesco Bronzi C.S.C. -

Mondo Movies E Grotteschi Cameo Gian

MONDO MOVIES E GROTTESCHI CAMEO: GIAN CARLO FUSCO, «POETA DA OSTERIA» AL CINEMA* ABSTRACT L’articolo esamina una parte delle collaborazioni cinematografiche di Gian Carlo Fu- sco, uno dei più celebri giornalisti italiani nel periodo che va dagli anni ’50 agli anni ’70: sotto esame sono posti i suoi commenti per vari “mondo movies” e la sua parte- cipazione, in qualità di sceneggiatore e talvolta di interprete, in film di genere (com- medie, polizieschi, ecc.). Nell’articolo sono considerati anche alcuni progetti non realizzati. Attraverso l’esame di questi film, l’articolo evidenzia i collegamenti con l’attività giornalistica e letteraria di Fusco e sottolinea l’atteggiamento con cui questo scrittore si è avvicinato al cinema. The article examines a part of the cinematographic collaborations of Gian Carlo Fus- co, one of the most famous Italian journalists in the period from the 50s to the 70s: his commentaries for various “mondo movies” are under scrutiny as well as his par- ticipation (as a screenwriter and sometimes as an actor) in genre films (comedies, detective stories, etc.), Some unrealized projects are also considered in the article. Through the examination of these films, the article highlights the links with the jour- nalistic and literary activity of Fusco and highlights the attitude with which this writ- er approached the cinema. Per il Vocabolarietto dell’Italiano incluso nell’Almanacco Bompiani del 1959, Gian Carlo Fusco, singolarissima figura di giornalista e scrittore, venne chiamato a scrive- re la voce Cinema. La compilò narrando un aneddoto riguardante Ermete Zacconi, il grande attore teatrale, che – interrogato dallo stesso Fusco nel marzo del 1945 – del cinema dava un giudizio sprezzante: «il cinematografo, strombazzato finché si vuo- le, […] sta al teatro come una scatola di carne conservata sta a una buona bistecca». -

AAISCSIS Program 2017

The American Association for Italian Studies and The Canadian Society for Italian Studies ANNUAL CONFERENCE 20-22 April 2017 The Ohio State University PLENARY SPEAKER Ruth Ben-Ghiat, New York University OTHER INVITED SPEAKERS Mario Badagliacca, Photographer Simone Castaldi, Hofstra University Fred Kuwornu, Filmmaker Lorella Zanardo (AAIS Women’s Studies Caucus Invited Speaker) SPECIAL GUESTS Aberta Lai, Director, The Istituto italiano di cultura di Chicago CONFERENCE COMMITTEE Sandra Parmegiani, University of Guelph Cristina Perissinotto, University of Ottawa Dana Renga, The Ohio State University Graduate Students Sebastiano Bazzichetto, University of Toronto Calvin Beckley, The Ohio State University Francesca Facchi, University of Toronto Jessica Henderson, The Ohio State University Dan Paul, The Ohio State University Cylia Queen, The Ohio State University OFFICERS OF THE AAIS Valerio Ferme, University of Colorado, Boulder, President Dana Renga, The Ohio State University, Vice-President Monica Seger, The College of William and Mary, Secretary Elena Past, Wayne State University, Treasurer Joe Francese, The University of Michigan, Senior Editor Italian Culture Carol Lazzaro-Weis, The University of Missouri-Columbia, Emeritus President OFFICERS OF THE CSIS Sandra Parmegiani, University of Guelph, President Cristina Perissinotto, University of Ottawa, Vice-President Mary Watt, University of Florida, Secretary Violetta Sutton, Brock University, Treasurer Luca Somigli, University of Toronto, Editor Quaderni d’italianistica Francesca Facchi,