Rev. of the Merton Tapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Reflection

VOL.48, NO.2 MAY 2017 Missionary Association of Mary Immaculate Provincial Reflection I am writing this on a 6 hour stopover with two remarkable Missionaries. One at the Hong Kong International Airport was a Spanish sister, Sister Rosario who, after having the privilege of spending after almost 40 years in northern India, a week and a half in the Philippines and and other places beforehand, came to then almost two weeks in Hong Kong/ Guangzhou at the age of 74 years, and China. I say a privilege because I have after 12 years there is going strong, with spent time with Oblates from the a passion for the people and the Lord Chinese. They continued, that although Asia/Oceania region and have visited which is infectious. The other missionary they appreciated the generosity and some of the inspiring places of their is Fr David Ullrich OMI who has spent the charity of so many, they were missionary outreach. almost 40 years in the Missions – Japan, concerned that perhaps the gifts the Hispanic Community in the USA and which came from wonderful people, The Oblates, whether in Cotabato, Manila, Mexico and now, 11 in China. They did did not meet the actual needs of the Hong Kong, Beijing or Guangzhou face not want me to mention their names people. They made mention that the many challenges (and rewards) that or their story. It needs to be told and needs of the people were not always we in the first world do not experience I will seek forgiveness when I next see in response to crises, such as the as they do. -

The Franciscan Crown in 1422, an Apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary Took Place in Assisi, to a Certain 7

History of the Franciscan Crown In 1422, an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary took place in Assisi, to a certain 7. Assumption & Coronation Franciscan novice, named James. As a child he had a custom of daily offering a crown Vision of Friar James of roses to our Blessed Mother. When he entered the Friar Minor, he became distressed that he would no longer be able to offer this type of gift. He considered leaving when our Lady appeared to him to give him comfort and showed him another daily offering he could do. Our Lady said : “In place of the flowers that soon wither and cannot always be found, you can weave for me a crown from the flowers of your prayers … Recite one Our Father and ten How to Pray the Franciscan Crown Hail Marys while recalling the Seven Joys I experienced.” Begin with the Sign of the Cross (no creed Friar James began at once to pray as directed. or opening prayers) Meanwhile, the novice master entered and 1. Announce the first Mystery, then pray saw an angel weaving a wreath of roses and one Our Father (no Glory Be). after every tenth rose, the angel, inserted a THE 2. Pray Ten Hail Mary’s while meditating golden lily. When the wreath was finished, FRANCISCAN on the Mystery. he placed it on Friar James’ head. The novice 3. Announce second Mystery and repeat master commanded the youth to tell him CROWN one and two through the seven decades. what he had been doing; and Friar James 4. -

{Download PDF} the Way of Unknowing : Expanding Spiritual

THE WAY OF UNKNOWING : EXPANDING SPIRITUAL HORIZONS THROUGH MEDITATION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Main | 144 pages | 30 Apr 2012 | CANTERBURY PRESS NORWICH | 9781848251182 | English | London, United Kingdom The Way of Unknowing : Expanding Spiritual Horizons Through Meditation PDF Book More recently, the practices of Christian Meditation through the World Community for Christian Meditation , and Centering Prayer represent contemporary expressions of the rich tradition of Christian meditation. By July , we had 76 people registered, a number that far exceeded my wildest dreams. Although mystical experiences of divine warmth, sweetness, and song may have some spiritual value, they will often remain distractions to you in the process of piercing the cloud of unknowing So keep lifting your love up to that cloud. But not everyone is going to get it. With one click, I was in the video chapel with about 14 other people from six different countries. Do you remember what happened to the greedy beasts who approached the cloud of unknowing on Mount Sinai? More importantly, these generally good thoughts can still distract you from the contemplative life: the deeper work of loving God in the darkness. When out walking somewhere, have you ever followed your feet while being curious about where they might lead? Columba arrived in the 6 th century to found a monastery and give birth to Celtic Christianity in Scotland. If this prayer practice resonates with you, then I urge you to read these words of mine again. I needed to take this deep book about meditation in the context of Christianity in small doses, reading it over a period of months, even though it is fairly short. -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

Celebrating 90 Years of Monastic Life. 1927-2017

LENSTAL ABBEY CHRONICLE Celebrating 90 years of GLENSTAL ABBEY monastic life. Murroe, Co Limerick www.glenstal.org 1927-2017 www.glenstal.com (061)621000 S T A Y I N TOUCH WITH G L E N S T A L ABBEY If you would like to receive emails from Glenstal about events and other goings on please join our email list on our website. You can decide what type of emails you will receive and can change this at any stage. Your data will not be used for any other purpose. 1 | P a g e CELEBRATING 90 YEARS OF MONASTIC LIFE 1 9 2 7 - 2 0 1 7 Welcome Contents On the 90th anniversary of our foundation it is our pleasure to share Where in the World…… page 3 with you, friends, benefactors, Oblates at Glenstal….. page 6 parents, students, colleagues and School Choir…………… page 8 visitors, something of the variety and richness of life here in Glenstal Out of Africa…………… page 10 Abbey. In the pages of this My Year in Glenstal Chronicle we hope to bring alive and UL…………………… page 13 the place which we are privileged Glenstal Abbey Farm… page 14 to call home. Thinking of Monastic Life……………………….. page 15 We have come a very long Life as a Novice……….. page 15 way from those early days when the first Belgian monks arrived here Malartú Daltaí le back in 1927. What has been Scoileanna thar Lear…. page 18 achieved is thanks in no small Guest House……………. page 19 measure to the kindness and Retreat Days……………. -

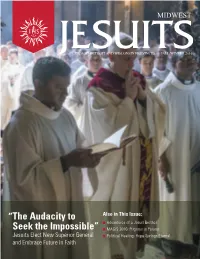

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr. -

Benedictionary.Pdf

INTRODUCTION The inspiration for this little booklet comes from two sources. The first source is a booklet developed in 1997 by Father GeorgeW. Traub, S.j., titled "Do You Speak Ignatian? A Glossary ofTerms Used in Ignatian and]esuit Circles." The booklet is published by the Ignatian Programs/Spiritual Development offICe of Xavier University, Cincinnati, Ohio. The second source, Beoneodicotionoal)', a pamphlet published by the Admissions Office of Benedictine University, was designed to be "a useful reference guide to help parents and students master the language of the college experience at Benedictine University." This booklet is not an alphabetical glossary but a directory to various offices and services. Beoneodicotio7loal)' II provides members of the campus community, and other interested individuals, with an opportunity to understand some of the specific terms used by Benedictine men and women. \\''hile Benedictine University makes a serious attempt to have all members of the campus community understand the "Benedictine Values" that underlie the educational work of the University, we hope this booklet will take the mystery out of some of the language used commonly among Benedictine monastics. This booklet was developed by Fr. David Turner, a,S.B., as part of the work of the Center for Mission and Identity at Benedictine University. I ABBESS The superior of a monastery of women, established as an abbey, is referred to as an abbess.. The professed members of the abbey are usually referred to as nuns. The abbess is elected to office following the norms contained in the proper law of the Congregation ohvhich the abbey is a member. -

Glossary of Chichewa Terms

01 Chewa Prelims copy 2/7/12 10:09 Page xxvi Glossary of Chichewa terms Akafula/Batwa Original inhabitants of Malawi prior to the settle - Chiwongo Clan name (inherited through father) ment of Bantu-speaking peoples. A hunter-gatherer society Dambule Major commemoration for the dead (the ancestors), Akunjira The novice master, who welcomes the initiate and held annually by a village or villages (now rare) supervises the initiation Dambwe The secret place where gule characters are made and Ankhoswe (sing. nkhoswe ) Guardians of the marriage bond where dancers transform into animals and spirits (cf. Anthumba Captives (of war) chilombo and mzimu ). Normally located near a graveyard Atsabwalo The Nyau member responsible for the bwalo Dona A European lady (dancing arena) Dzala Rubbish pit. A liminal area where some of the instruction Bwalo Arena for the performance of gule wamkulu and other takes place during girls’ initiation and where some gule rituals; ‘centre’ of the village anoint themselves with ashes in order to associate Chamba The drug hemp; marijuana themselves with the dead Chatuluka Retired village chief Fisi Literally, ‘hyena’. A surrogate husband for the purpose of Chibiya Ngoni kilt ritual intercourse (to awaken sexually an initiated girl who Chihata Beaded belt or vest of the Ngoni does not have a husband) or for generating a child in a Chikafula Language of the Akafula, which sounds like ‘coughing’ childless marriage Chikamwini Uxorilocal marriage system where the husband Galu wanga chimbwala A mini-structure of a dog that fails to moves to live in his wife’s village follow its owner and is seen as unfaithful Chikhuthe Shelters where beer is brewed for rituals Gocho Term of derision for an impotent man Chilale Palm leaves, commonly woven to form outer skin of Gule wamkulu The ‘great dance’ of the Chewa, involving structures masked and costumed dancers and structures Chilamu Joking, light hearted relationship between brother- and Inyago Carved and costumed characters of the Yao. -

Remembering Sri Sarada Devi's Disciple

Copyright 2010 by Esther Warkov All rights reserved First printed in 2010 Cover Design by Gregory Fields No portion of this book or accompanying DVD may be reproduced anywhere (including the internet) or used in any form, or by any means (written, electronic, mechanical, or other means now known or hereafter invented including photocopying, duplicating, and recording) without prior written permission from the author/publisher. Exceptions are made for brief excerpts used in published reviews. Photographs on the accompanying disc may be printed for home use only. The song appearing on the accompanying disc may be duplicated and used for non-commercial purposes only. ISBN 978-0-578-04660-0 To order copies of this publication please visit Compendium Publications www.compendiumpublications.com or contact the author at [email protected] (Seattle, WA, USA) Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements v About the Contributors ix Remembrances from Monastic Devotees Swami Yogeshananda 3 Swami Damodarananda “Swami Aseshanandaji: Humble and Inspiring‖ 8 Swami Manishananda “Reminiscences of Swami Aseshananda‖ 11 Pravrajika Gayatriprana 15 Pravrajika Brahmaprana “Reminiscences of Swami Aseshananda‖ 25 Swami Harananda 33 Pravrajika Sevaprana 41 Swami Tathagatananda ―Reminiscences of Revered Swami Aseshanandaji‖ 43 Swami Brahmarupananda “Swami Aseshananda As I Saw Him‖ 48 Anonymous Pravrajika 50 Vimukta Chaitanya 51 Six Portraits of Swami Aseshananda Michael Morrow (Vijnana) 55 Eric Foster 60 Anonymous ―Initiation Accounts‖ 69 Alex S. Johnson ―The Influence and Example of a Great Soul‖ 72 Ralph Stuart 74 Jon Monday (Dharmadas) ―A Visit with a Swami in America‖ 88 The Early Years: 1955-1969 Vera Edwards 95 Marina Sanderson 104 Robert Collins, Ed. -

FRANCISCAN CROWN ROSARY the Franciscan Crown Rosary Is a Seven Decade Rosary in Honor of the Seven Joys of Mary

THE FRANCISCAN CROWN ROSARY The Franciscan Crown Rosary is a seven decade Rosary in honor of the Seven Joys of Mary. How to pray the Franciscan Crown Rosary Begin with the sign of the Cross (there is no Creed or opening prayers) 1. At the first decade, announce the first mystery; then say one Our Father on the fifth bead from the Cross 2. Say one Hail Mary on each of the ten beads. 3. Announce the second mystery & repeat steps 1 through the 7th decade. 4. Say Two Hail Mary's to complete 72 years of Mary's life on earth on the fourth and third beads from the Cross. 5. Say Our Father on the 2nd bead from the Cross & say Hail Mary on the bead closest to the Cross for the intentions of the Holy Father. Seven Joys of Our Lady First joy of Mary : The Annunciation “behold the handmaid of the Lord, be it done to me according to your word.” Luke 1:26-33 R: May I become your humble servant, Lord. Second joy of' Mary : The Visitation “Rising up, Mary went into the hill country and saluted her cousin Elizabeth.” Luke 1:39-47 R: Grant us true love of neighbor, Lord. Third Joy of Mary: The Nativity “She brought fourth her first born son...and laid him in a manger.” Luke 2:4-7 R: Give us true poverty of spirit, Lord. Fourth joy of Mary : Adoration of the Magi “Following the star the Magi found Jesus, adored him and presented gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.” Matt 2:9-11 R: Help me obey all just laws. -

Peter Abelard's Carmen Ad Astralabium and Medieval Parent-Child Didactic Texts

Juanita Feros Ruys (Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney) Peter Abelard's Carmen ad Astralabium and Medieval Parent-Child Didactic Texts: The Evidence for Parent-Child Relationships in the Middle Ages In his Introduction to this volume, Albrecht Classen relates the story of Konrad von Wiirzburg's Engelhard, and asks whether the parental behaviors displayed in medieval narratives can be taken as indicative of real medieval parental attitudes. This is a key question, since a scarcity of other sources often requires medievalists to press fictional narratives into service in this way, as for example Doris Desclais Berkvam's study of childhood and maternity in the romances and epics of medieval France,1 and Classen's own study of family life in medieval German literary sources indicate.2 A modern reader of the actions that Engelhard undertakes and the arguments he espouses might find them so contradictory as to nullify their usefulness as evidence of true medieval attitudes towards children, but this is not necessarily the case. In fact, Engelhard's views match remarkably well with those stated by the twelfth-century French philosopher and theologian Peter Abelard, who was himself the father of a son named Astralabe. Like the fictional Engelhard, Abelard is capable of expressing great parental love, and his Planctus Jacob super filios suos (Lament of Jacob over his Sons) contains touching images of the elderly Jacob recalling with fondness the lisping first words of his son Benjamin: "informes in facie teneri sermones / omnem eloquentie favum transcendentes" ("as yet unformed upon your lips, the tender words surpassing 1 I wish to thank the Australian Research Council for the provision of a post-doctoral Fellowship which has funded this research. -

The Modern Novitiate

THE MODERN NOVITIATE By TIMOTHY QUINLAN T lS NOW three years since Renovationis Causam was promulgated. Many changes have since been introduced into refigious forma- tion and are still being made. Consequently it is as valid today I as it was in I969 to say that 'new regulations of a binding and definitive character cannot be framed without taking into account reasonably protracted experiments conducted over a sufficiently wide area, and the factual judgements based on them'? Those who would like a more solid legal structure than the present situation offers may find it sobering to read in the same document that 'the Church, guided by the experience which became hers in the course of centuries, was concerned gradually to bnild up a body of canonical laws which in times gone by contributed in large measure to the strength and growth of religious life'. ~ Law should be seen not as a rigid scaffolding, external to the structure it supports, but rather as a skeletal system which is dynamic, flexible and supportive within a growing organism. This article will examine the prescriptions for the novitiate set out in Renovationis Causam and give examples of how these are working in practice. My remarks will be directed more immediately to Institutes devoted to apostolic works and are applicable, within limits, to both men and women religious. A detailed commentary on the text has already been made by Fr Paul Molinari, 3 so the ground covered there will not be retraced except by way of summary. The document clearly recognizes the complexity of situations and the extraordinary diversity of apostolic activities undertaken by religious.