Labile Sex Expression in Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 5 Chapter 1 Introduction I. LIFE CYCLES and DIVERSITY of VASCULAR PLANTS the Subjects of This Thesis Are the Pteri

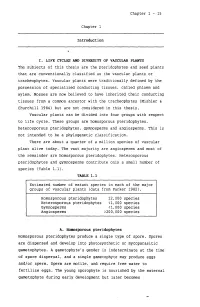

Chapter 1-15 Chapter 1 Introduction I. LIFE CYCLES AND DIVERSITY OF VASCULAR PLANTS The subjects of this thesis are the pteridophytes and seed plants that are conventionally classified as the vascular plants or tracheophytes. Vascular plants were traditionally defined by the possession of specialized conducting tissues, called phloem and xylem. Mosses are now believed to have inherited their conducting tissues from a common ancestor with the tracheophytes (Mishler & Churchill 1984) but are not considered in this thesis. Vascular plants can be divided into four groups with respect to life cycle. These groups are homosporous pteridophytes, heterosporous pteridophytes, gymnosperms and angiosperms. This is not intended to be a phylogenetic classification. There are about a quarter of a million species of vascular plant alive today. The vast majority are angiosperms and most of the remainder are homosporous pteridophytes. Heterosporous pteridophytes and gymnosperms contribute only a small number of species (Table 1.1). TABLE 1.1 Estimated number of extant species in each of the major groups of vascular plants (data from Parker 1982). Homosporous pteridophytes 12,000 species Heterosporous pteridophytes <1,000 species Gymnosperms <1,000 species Angiosperms >200,000 species A. Homosporous pteridophytes Homosporous pteridophytes produce a single type of spore. Spores are dispersed and develop into photosynthetic or mycoparasitic gametophytes. A gametophyte's gender is indeterminate at the time of spore dispersal, and a single gametophyte may produce eggs and/or sperm. Sperm are motile, and require free water to fertilize eggs. The young sporophyte is nourished by the maternal gametophyte during early development but later becomes Chapter 1-16 nutritionally independent. -

Auxin Regulation Involved in Gynoecium Morphogenesis of Papaya Flowers

Zhou et al. Horticulture Research (2019) 6:119 Horticulture Research https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-019-0205-8 www.nature.com/hortres ARTICLE Open Access Auxin regulation involved in gynoecium morphogenesis of papaya flowers Ping Zhou 1,2,MahparaFatima3,XinyiMa1,JuanLiu1 and Ray Ming 1,4 Abstract The morphogenesis of gynoecium is crucial for propagation and productivity of fruit crops. For trioecious papaya (Carica papaya), highly differentiated morphology of gynoecium in flowers of different sex types is controlled by gene networks and influenced by environmental factors, but the regulatory mechanism in gynoecium morphogenesis is unclear. Gynodioecious and dioecious papaya varieties were used for analysis of differentially expressed genes followed by experiments using auxin and an auxin transporter inhibitor. We first compared differential gene expression in functional and rudimentary gynoecium at early stage of their development and detected significant difference in phytohormone modulating and transduction processes, particularly auxin. Enhanced auxin signal transduction in rudimentary gynoecium was observed. To determine the role auxin plays in the papaya gynoecium, auxin transport inhibitor (N-1-Naphthylphthalamic acid, NPA) and synthetic auxin analogs with different concentrations gradient were sprayed to the trunk apex of male and female plants of dioecious papaya. Weakening of auxin transport by 10 mg/L NPA treatment resulted in female fertility restoration in male flowers, while female flowers did not show changes. NPA treatment with higher concentration (30 and 50 mg/L) caused deformed flowers in both male and female plants. We hypothesize that the occurrence of rudimentary gynoecium patterning might associate with auxin homeostasis alteration. Proper auxin concentration and auxin homeostasis might be crucial for functional gynoecium morphogenesis in papaya flowers. -

Genetics of Dioecy and Causal Sex Chromosomes in Plants

c Indian Academy of Sciences REVIEW ARTICLE Genetics of dioecy and causal sex chromosomes in plants SUSHIL KUMAR1,2∗, RENU KUMARI1,2 and VISHAKHA SHARMA1 1SKA Institution of Research, Education and Development (SKAIRED), 4/11 SarvPriya Vihar, New Delhi 110 016, India 2National Institute of Plant Genome Research, Aruna Asaf Ali Marg, New Delhi 110 067, India Abstract Dioecy (separate male and female individuals) ensures outcrossing and is more prevalent in animals than in plants. Although it is common in bryophytes and gymnosperms, only 5% of angiosperms are dioecious. In dioecious higher plants, flowers borne on male and female individuals are, respectively deficient in functional gynoecium and androecium. Dioecy is inherited via three sex chromosome systems: XX/XY, XX/X0 and WZ/ZZ, such that XX or WZ is female and XY, X0 or ZZ are males. The XX/XY system generates the rarer XX/X0 and WZ/ZZ systems. An autosome pair begets XY chromosomes. A recessive loss-of-androecium mutation (ana) creates X chromosome and a dominant gynoecium-suppressing (GYS) mutation creates Y chromosome. The ana/ANA and gys/GYS loci are in the sex-determining region (SDR) of the XY pair. Accumulation of inversions, deleterious mutations and repeat elements, especially transposons, in the SDR of Y suppresses recombination between X and Y in SDR, making Y labile and increasingly degenerate and heteromorphic from X. Continued recombination between X and Y in their pseudoautosomal region located at the ends of chromosomal arms allows survival of the degenerated Y and of the species. Dioecy is presumably a component of the evolutionary cycle for the origin of new species. -

Heterospory: the Most Iterative Key Innovation in the Evolutionary History of the Plant Kingdom

Biol. Rej\ (1994). 69, l>p. 345-417 345 Printeii in GrenI Britain HETEROSPORY: THE MOST ITERATIVE KEY INNOVATION IN THE EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF THE PLANT KINGDOM BY RICHARD M. BATEMAN' AND WILLIAM A. DiMlCHELE' ' Departments of Earth and Plant Sciences, Oxford University, Parks Road, Oxford OXi 3P/?, U.K. {Present addresses: Royal Botanic Garden Edinburiih, Inverleith Rojv, Edinburgh, EIIT, SLR ; Department of Geology, Royal Museum of Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh EHi ijfF) '" Department of Paleohiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC^zo^bo, U.S.A. CONTENTS I. Introduction: the nature of hf^terospon' ......... 345 U. Generalized life history of a homosporous polysporangiophyle: the basis for evolutionary excursions into hetcrospory ............ 348 III, Detection of hcterospory in fossils. .......... 352 (1) The need to extrapolate from sporophyte to gametophyte ..... 352 (2) Spatial criteria and the physiological control of heterospory ..... 351; IV. Iterative evolution of heterospory ........... ^dj V. Inter-cladc comparison of levels of heterospory 374 (1) Zosterophyllopsida 374 (2) Lycopsida 374 (3) Sphenopsida . 377 (4) PtiTopsida 378 (5) f^rogymnospermopsida ............ 380 (6) Gymnospermopsida (including Angiospermales) . 384 (7) Summary: patterns of character acquisition ....... 386 VI. Physiological control of hetcrosporic phenomena ........ 390 VII. How the sporophyte progressively gained control over the gametophyte: a 'just-so' story 391 (1) Introduction: evolutionary antagonism between sporophyte and gametophyte 391 (2) Homosporous systems ............ 394 (3) Heterosporous systems ............ 39(1 (4) Total sporophytic control: seed habit 401 VIII. Summary .... ... 404 IX. .•Acknowledgements 407 X. References 407 I. I.NIRODUCTION: THE NATURE OF HETEROSPORY 'Heterospory' sensu lato has long been one of the most popular re\ie\v topics in organismal botany. -

The Diversity of Plant Sex Chromosomes Highlighted Through Advances in Genome Sequencing

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review The Diversity of Plant Sex Chromosomes Highlighted through Advances in Genome Sequencing Sarah Carey 1,2 , Qingyi Yu 3,* and Alex Harkess 1,2,* 1 Department of Crop, Soil, and Environmental Sciences, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849, USA; [email protected] 2 HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Huntsville, AL 35806, USA 3 Texas A&M AgriLife Research, Texas A&M University System, Dallas, TX 75252, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] (Q.Y.); [email protected] (A.H.) Abstract: For centuries, scientists have been intrigued by the origin of dioecy in plants, characterizing sex-specific development, uncovering cytological differences between the sexes, and developing theoretical models. Through the invention and continued improvements in genomic technologies, we have truly begun to unlock the genetic basis of dioecy in many species. Here we broadly review the advances in research on dioecy and sex chromosomes. We start by first discussing the early works that built the foundation for current studies and the advances in genome sequencing that have facilitated more-recent findings. We next discuss the analyses of sex chromosomes and sex-determination genes uncovered by genome sequencing. We synthesize these results to find some patterns are emerging, such as the role of duplications, the involvement of hormones in sex-determination, and support for the two-locus model for the origin of dioecy. Though across systems, there are also many novel insights into how sex chromosomes evolve, including different sex-determining genes and routes to suppressed recombination. We propose the future of research in plant sex chromosomes should involve interdisciplinary approaches, combining cutting-edge technologies with the classics Citation: Carey, S.; Yu, Q.; to unravel the patterns that can be found across the hundreds of independent origins. -

Cryptic Dioecy of Symplocos Wikstroemiifolia Hayata (Symplocaceae) in Taiwan

Botanical Studies (2011) 52: 479-491. REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY Cryptic dioecy of Symplocos wikstroemiifolia Hayata (Symplocaceae) in Taiwan Yu-Chen WANG and Jer-Ming HU* Institute of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, National Taiwan University, Taipei 10617, Taiwan (Received November 25, 2010; Accepted March 24, 2011) ABSTRACT. Symplocos wikstroemiifolia Hayata is one of the few morphologically androdioecious spe- cies in Symplocaceae. Although this species has been proposed as cryptically dioecious, little is known about its patterns of sexual expression in the field. We studied the breeding system and reproductive biology of S. wikstroemiifolia in Taiwan. Field investigations showed that anthers of most morphologically hermaphroditic flowers did not produce pollen grains; thus, this flower type should be considered female. Nearly all flowering individuals produced only male or female flowers. The sex ratios were slightly male-biased, but did not sig- nificantly deviate from 1:1, congruent with the proposed cryptic dioecy status. However, two individuals pro- duced flowers that may have been functionally hermaphroditic, suggesting a variation of sexual expression in S. wikstroemiifolia. There were about 12 stamens per male flower but only five staminodes per female flower. No locules and ovules existed in the male flowers, while two locules within the ovary of the female flowers con- tained four ovules each (two large, two small). Male individuals produced cymes and thyrses, whereas female individuals only produced cymes. Some of these morphological characteristics differed from those previously described. Anthesis of most male and female flowers began before dawn and lasted for one to two days. Nev- ertheless, anther dehiscence, which only occurred under dry conditions, was not restricted to a specific time period during the day. -

Evolutionary Consequences of Dioecy in Angiosperms: the Effects of Breeding System on Speciation and Extinction Rates

EVOLUTIONARY CONSEQUENCES OF DIOECY IN ANGIOSPERMS: THE EFFECTS OF BREEDING SYSTEM ON SPECIATION AND EXTINCTION RATES by JANA C. HEILBUTH B.Sc, Simon Fraser University, 1996 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Zoology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA July 2001 © Jana Heilbuth, 2001 Wednesday, April 25, 2001 UBC Special Collections - Thesis Authorisation Form Page: 1 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada http://www.library.ubc.ca/spcoll/thesauth.html ABSTRACT Dioecy, the breeding system with male and female function on separate individuals, may affect the ability of a lineage to avoid extinction or speciate. Dioecy is a rare breeding system among the angiosperms (approximately 6% of all flowering plants) while hermaphroditism (having male and female function present within each flower) is predominant. Dioecious angiosperms may be rare because the transitions to dioecy have been recent or because dioecious angiosperms experience decreased diversification rates (speciation minus extinction) compared to plants with other breeding systems. -

Evolution of the Schistosomes (Digenea: Schistosomatoidea): the Origin of Dioecy and Colonization of the Venous System

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 12-1997 Evolution of the Schistosomes (Digenea: Schistosomatoidea): The Origin of Dioecy and Colonization of the Venous System Thomas R. Platt St. Mary's College Daniel R. Brooks University of Toronto, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Platt, Thomas R. and Brooks, Daniel R., "Evolution of the Schistosomes (Digenea: Schistosomatoidea): The Origin of Dioecy and Colonization of the Venous System" (1997). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 229. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/229 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. J. Parasitol., 83(6), 1997 p. 1035-1044 ? American Society of Parasitologists 1997 EVOLUTIONOF THE SCHISTOSOMES(DIGENEA: SCHISTOSOMATOIDEA): THE ORIGINOF DIOECYAND COLONIZATIONOF THE VENOUS SYSTEM Thomas R. Platt and Daniel R. Brookst Department of Biology, Saint Mary's College, Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 ABSTRACT: Trematodesof the family Schistosomatidaeare -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

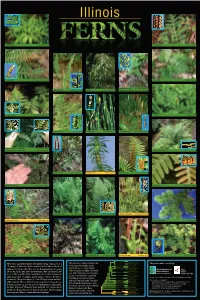

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Cryptic Dioecy in Mussaenda Pubescens (Rubiaceae): a Species with Stigma-Height Dimorphism

Annals of Botany 106: 521–531, 2010 doi:10.1093/aob/mcq146, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Cryptic dioecy in Mussaenda pubescens (Rubiaceae): a species with stigma-height dimorphism Ai-Min Li1,2,†, Xiao-Qin Wu1,†, Dian-Xiang Zhang1,* and Spencer C. H. Barrett3 1Key Laboratory of Plant Resources Conservation and Sustainable Utilization, South China Botanical Garden, The Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guangzhou 510650, China, 2Department of Life Sciences, Huaihua College, Huaihua 418008, China and 3Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 3B2 * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] †These authors contributed equally to this work. Downloaded from Received: 12 April 2010 Returned for revision: 11 May 2010 Accepted: 17 June 2010 Published electronically: 19 July 2010 † Background and Aims Evolutionary transitions from heterostyly to dioecy have been proposed in several angiosperm families, particularly in Rubiaceae. These transitions involve the spread of male and female sterility mutations resulting in modifications to the gender of ancestral hermaphrodites. Despite sustained interest in the aob.oxfordjournals.org gender strategies of plants, the structural and developmental bases for transitions in sexual systems are poorly understood. † Methods Here, floral morphology, patterns of fertility, pollen-tube growth and floral development are investi- gated in two populations of the scandent shrub Mussaenda pubescens (Rubiaceae), native to southern China, by means of experimental and open-pollinations, light microscopy, fluorescence microscopy and scanning elec- tron microscopy combined with paraffin sectioning. † Key Results Mussaenda pubescens has perfect (hermaphroditic) flowers and populations with two style-length morphs but only weak differentiation in anther position (stigma-height dimorphism). -

Mosses and Ferns

Mosses and Ferns • How did they evolve from Protists? Moss and Fern Life Cycles Group 1: Seedless, Nonvascular Plants • Live in moist environments to reproduce • Grow low to ground to retain moisture (nonvascular) • Lack true leaves • Common pioneer species during succession • Gametophyte most common (dominant) • Ex: Mosses, liverworts, hornworts Moss Life Cycle 1)Moss 2) Through water, 3) Diploid sporophyte 4) Sporophyte will gametophytes sperm from the male will grow from zygote create and release grow near the gametophyte will haploid spores ground swim to the female (haploid stage) gametophyte to create a diploid zygote Diploid sporophyte . zygo egg zygo te egg te zygo zygo egg egg te te male male female female female male female male Haploid gametophytes 5) Haploid 6) The process spores land repeats and grow into new . gametophytes . Haploid gametophytesground . sporophyte . zygo egg zygo te egg te zygo zygo egg egg te te male male female female female male female male Haploid gametophytes • Vascular system allows Group 2: Seedless, – Taller growth – Nutrient transportation Vascular Plants • Live in moist environments – swimming sperm • Gametophyte stage – Male gametophyte: makes sperm – Female gametophyte: makes eggs – Sperm swims to fertilize eggs • Sporophyte stage – Spores released into air – Spores land and grow into gametophyte • Ex: Ferns, Club mosses, Horsetails Fern Life Cycle 1) Sporophyte creates and releases haploid spores Adult Sporophyte . ground 2) Haploid spores land in the soil . ground 3) From the haploid spores, gametophyte grows in the soil Let’s zoom in Fern gametophytes are called a prothallus ground 4) Sperm swim through water from the male parts (antheridium) to the female parts (archegonia)…zygote created Let’s zoom back out zygo zygo egg egg te te zygo egg te 5) Diploid sporophyte grows from the zygote sporophyte Fern gametophytes are called a prothallus ground 6) Fiddle head uncurls….fronds open up 7) Cycle repeats -- Haploid spores created and released . -

Plant Reproduction

AccessScience from McGraw-Hill Education Page 1 of 10 www.accessscience.com Plant reproduction Contributed by: Scott D. Russell Publication year: 2014 The formation of a new plant that is either an exact copy or recombination of the genetic makeup of its parents. There are three types of plant reproduction considered here: (1) vegetative reproduction, in which a vegetative organ forms a clone of the parent; (2) asexual reproduction, in which reproductive components undergo a nonsexual form of production of offspring without genetic rearrangement, also known as apomixis; and (3) sexual reproduction, in which meiosis (reduction division) leads to formation of male and female gametes that combine through syngamy (union of gametes) to produce offspring. See also: PLANT; PLANT PHYSIOLOGY. Vegetative reproduction Unlike animals, plants may be readily stimulated to produce identical copies of themselves through cloning. In animals, only a few cells, which are regarded as stem cells, are capable of generating cell lineages, organs, or new organisms. In contrast, plants generate or produce stem cells from many plant cells of the root, stem, or leaf that are not part of an obvious generative lineage—a characteristic that has been known as totipotency, or the general ability of a single cell to regenerate a whole new plant. This ability to establish new plants from one or more cells is the foundation of plant biotechnology. In biotechnology, a single cell may be used to regenerate new organisms that may or may not genetically differ from the original organism. If it is identical to the parent, it is a clone; however, if this plant has been altered through molecular biology, it is known as a genetically modified organism (GMO).