Jewel Theatre Audience Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Nats Go Home': Modernism, Television and Three BBC

‘Nats go home’: modernism, television and three BBC productions of Ibsen (1971-1974) Article Accepted Version Smart, B. (2016) ‘Nats go home’: modernism, television and three BBC productions of Ibsen (1971-1974). Ibsen Studies, 16 (1). pp. 37-70. ISSN 1502-1866 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15021866.2016.1180869 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/71899/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15021866.2016.1180869 To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15021866.2016.1180869 Publisher: Routledge All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online ‘Nats go home’: Modernism, television and three BBC productions of Ibsen (1971-1974) In 1964 theatre journal Encore published ‘Nats go home’, a polemical article by television screenwriter Troy Kennedy Martin. The manifesto for dramatic techniques innovated at BBC Television in the 1960s subsequently proved highly influential and is frequently cited in histories of British television drama (Caughie 2000, Cooke 2003, Hill 2007). The article called for the rejection of naturalism in television drama, and for new modernist forms to be created in its place. Kennedy Martin identified ‘nat’ television drama as deriving from nineteenth century theatrical traditions, complaining that it looked “to Ibsen and Shaw for guidance” (23). -

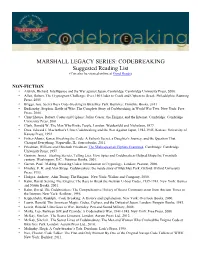

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

The Journal of William Morris Studies

The Journal of William Morris Studies volume xx, number 4, summer 2014 Editorial – Pearls for the ancestors Patrick O’Sullivan 3 William Morris’s unpublished Arthurian translations, Roger Simpson 7 William Morris’s paternal ancestry Dorothy Coles†, revised Barbara Lawrence 19 The ancestry of William Morris: the Worcester connection David Everett 34 Jane Morris and her male correspondents Peter Faulkner 60 ‘A clear Xame-like spirit’: Georgiana Burne-Jones and Rottingdean, 1904-1920 Stephen Williams 79 Reviews. Edited by Peter Faulkner Linda Parry, William Morris Textiles (Lynn Hulse) 91 Mike and Kate Lea, eds, W.G Collingwood’s Letters from Iceland: Travels in Iceland 1897 (John Purkis) 95 Gary Sargeant, Friends and InXuences: The Memoirs of an Artist (John Purkis) 98 the journal of william morris studies . summer 2014 Barrie and Wendy Armstrong, The Arts and Crafts Movement in the North East of England (Martin Haggerty) 100 Barrie and Wendy Armstrong, The Arts and Crafts Movement in Yorkshire (Ian Jones) 103 Annette Carruthers, The Arts and Crafts Movement in Scotland. A History (Peter Faulkner) 106 Laura Euler, Arts and Crafts Embroidery (Linda Parry) 110 Clive Bloom, Victoria’s Madmen. Revolution and Alienation (Peter Faulkner) 111 Hermione Lee, Penelope Fitzgerald: A Life (Christine Poulsom) 114 Carl Levy, ed, Colin Ward. Life,Times and Thought (Peter Faulkner) 117 Rosalind Williams, The Triumph of the Human Empire. Verne, Morris and Stevenson at the end of the world (Patrick O’Sullivan) 120 Guidelines for Contributors 124 Notes on Contributors 126 ISSN: 1756-1353 Editor: Patrick O’Sullivan ([email protected]) Reviews Editor: Peter Faulkner ([email protected]) Designed by David Gorman ([email protected]) Printed by the Short Run Press, Exeter, UK (http://www.shortrunpress.co.uk/) All material printed (except where otherwise stated) copyright the William Mor- ris Society. -

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 Min)

September 6, 2011 (XXIII:2) Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, PYGMALION (1938, 96 min) Directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard Written by George Bernard Shaw (play, scenario & dialogue), W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple (uncredited), Anatole de Grunwald (uncredited), Kay Walsh (uncredited) Produced by Gabriel Pascal Original Music by Arthur Honegger Cinematography by Harry Stradling Edited by David Lean Art Direction by John Bryan Costume Design by Ladislaw Czettel (as Professor L. Czettel), Schiaparelli (uncredited), Worth (uncredited) Music composed by William Axt Music conducted by Louis Levy Leslie Howard...Professor Henry Higgins Wendy Hiller...Eliza Doolittle Wilfrid Lawson...Alfred Doolittle Marie Lohr...Mrs. Higgins Scott Sunderland...Colonel George Pickering GEORGE BERNARD SHAW [from Wikipedia](26 July 1856 – 2 Jean Cadell...Mrs. Pearce November 1950) was an Irish playwright and a co-founder of the David Tree...Freddy Eynsford-Hill London School of Economics. Although his first profitable writing Everley Gregg...Mrs. Eynsford-Hill was music and literary criticism, in which capacity he wrote many Leueen MacGrath...Clara Eynsford Hill highly articulate pieces of journalism, his main talent was for Esme Percy...Count Aristid Karpathy drama, and he wrote more than 60 plays. Nearly all his writings address prevailing social problems, but have a vein of comedy Academy Award – 1939 – Best Screenplay which makes their stark themes more palatable. Shaw examined George Bernard Shaw, W.P. Lipscomb, Cecil Lewis, Ian Dalrymple education, marriage, religion, government, health care, and class privilege. ANTHONY ASQUITH (November 9, 1902, London, England, UK – He was most angered by what he perceived as the February 20, 1968, Marylebone, London, England, UK) directed 43 exploitation of the working class. -

Ull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater

Hull History Centre: Papers of Alan Plater U DPR Papers of Alan Plater 1936-2012 Accession number: 1999/16, 2004/23, 2013/07, 2013/08, 2015/13 Biographical Background: Alan Frederick Plater was born in Jarrow in April 1935, the son of Herbert and Isabella Plater. He grew up in the Hull area, and was educated at Pickering Road Junior School and Kingston High School, Hull. He then studied architecture at King's College, Newcastle upon Tyne, becoming an Associate of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1959 (since lapsed). He worked for a short time in the profession, before becoming a full-time writer in 1960. His subsequent career has been extremely wide-ranging and remarkably successful, both in terms of his own original work, and his adaptations of literary works. He has written extensively for radio, television, films and the theatre, and for the daily and weekly press, including The Guardian, Punch, Listener, and New Statesman. His writing credits exceed 250 in number, and include: - Theatre: 'A Smashing Day'; 'Close the Coalhouse Door'; 'Trinity Tales'; 'The Fosdyke Saga' - Film: 'The Virgin and the Gypsy'; 'It Shouldn't Happen to a Vet'; 'Priest of Love' - Television: 'Z Cars'; 'The Beiderbecke Affair'; 'Barchester Chronicles'; 'The Fortunes of War'; 'A Very British Coup'; and, 'Campion' - Radio: 'Ted's Cathedral'; 'Tolpuddle'; 'The Journal of Vasilije Bogdanovic' - Books: 'The Beiderbecke Trilogy'; 'Misterioso'; 'Doggin' Around' He received numerous awards, most notably the BAFTA Writer's Award in 1988. He was made an Honorary D.Litt. of the University of Hull in 1985, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1985. -

Race in the Age of Obama Making America More Competitive

american academy of arts & sciences summer 2011 www.amacad.org Bulletin vol. lxiv, no. 4 Race in the Age of Obama Gerald Early, Jeffrey B. Ferguson, Korina Jocson, and David A. Hollinger Making America More Competitive, Innovative, and Healthy Harvey V. Fineberg, Cherry A. Murray, and Charles M. Vest ALSO: Social Science and the Alternative Energy Future Philanthropy in Public Education Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences Reflections: John Lithgow Breaking the Code Around the Country Upcoming Events Induction Weekend–Cambridge September 30– Welcome Reception for New Members October 1–Induction Ceremony October 2– Symposium: American Institutions and a Civil Society Partial List of Speakers: David Souter (Supreme Court of the United States), Maj. Gen. Gregg Martin (United States Army War College), and David M. Kennedy (Stanford University) OCTOBER NOVEMBER 25th 12th Stated Meeting–Stanford Stated Meeting–Chicago in collaboration with the Chicago Humanities Perspectives on the Future of Nuclear Power Festival after Fukushima WikiLeaks and the First Amendment Introduction: Scott D. Sagan (Stanford Introduction: John A. Katzenellenbogen University) (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) Speakers: Wael Al Assad (League of Arab Speakers: Geoffrey R. Stone (University of States) and Jayantha Dhanapala (Pugwash Chicago Law School), Richard A. Posner (U.S. Conferences on Science and World Affairs) Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit), 27th Judith Miller (formerly of The New York Times), Stated Meeting–Berkeley and Gabriel Schoenfeld (Hudson Institute; Healing the Troubled American Economy Witherspoon Institute) Introduction: Robert J. Birgeneau (Univer- DECEMBER sity of California, Berkeley) 7th Speakers: Christina Romer (University of Stated Meeting–Stanford California, Berkeley) and David H. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

Nomination Press Release

Brian Boyle, Supervising Producer Outstanding Voice-Over Nahnatchka Khan, Supervising Producer Performance Kara Vallow, Producer American Masters • Jerome Robbins: Diana Ritchey, Animation Producer Something To Dance About • PBS • Caleb Meurer, Director Thirteen/WNET American Masters Ron Hughart, Supervising Director Ron Rifkin as Narrator Anthony Lioi, Supervising Director Family Guy • I Dream of Jesus • FOX • Fox Mike Mayfield, Assistant Director/Timer Television Animation Seth MacFarlane as Peter Griffin Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars Episode II • Cartoon Network • Robot Chicken • Robot Chicken: Star Wars ShadowMachine Episode II • Cartoon Network • Seth Green, Executive Producer/Written ShadowMachine by/Directed by Seth Green as Robot Chicken Nerd, Bob Matthew Senreich, Executive Producer/Written by Goldstein, Ponda Baba, Anakin Skywalker, Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Imperial Officer Mike Lazzo, Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eeny Teeny Maya, Moe • Alex Bulkley, Producer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Corey Campodonico, Producer Century Fox Television Hank Azaria as Moe Syzlak Ollie Green, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer The Simpsons • The Burns And The Bees • Tom Root, Head Writer FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Hugh Davidson, Written by Century Fox Television Harry Shearer as Mr. Burns, Smithers, Kent Mike Fasolo, Written by Brockman, Lenny Breckin Meyer, Written by Dan Milano, Written by The Simpsons • Father Knows Worst • FOX • Gracie Films in Association with 20th Kevin Shinick, -

Stylised Worlds: Colour Separation Overlay in BBC Television Plays of the 1970S

Stylised Worlds: Colour Separation Overlay in BBC Television Plays of the 1970s Leah Panos Abstract This essay aims to understand and interrogate the use of Colour Separation Overlay (CSO) as a mode of experimental production and aesthetic innovation in television drama in the 1970s. It sets out to do this by describing, accounting for and evaluating CSO as a production technique, considering the role of key production personnel, and analysing four specific BBC productions. Deploying methodologies of archival research, practitioner interview, and close textual analysis, the essay also delivers a significant reassessment of the role of the producer and designer in the conceptualisation and realisation of small-screen dramatic fiction. Key words: studio, drama, single play, aesthetics, experimental, CSO, blue screen, designer The technique the BBC named Colour Separation Overlay (CSO), referred to as ‘Chromakey’ by ITV production companies and more commonly known as ‘blue screen’,1 was described by the author of a 1976 television writers’ training manual as ‘the biggest technological development in television in recent years’,2 and remains a principle underpinning contemporary special effects practice. This article will discuss the technique and identify some key figures within the TV industry who championed its use, whilst analysing a cycle of BBC dramas made during the 1970s and early 1980s that used CSO extensively. Although many programmes made during this period used this effect in some capacity, I will examine four aesthetically innovative, CSO-based BBC single plays which demonstrate two designers’ work with CSO: Eileen Diss designed the early CSO productions Candide (Play of the Month, TX: 16/02/73) and Alice Through the Looking Glass (TX: 25/12/73) and Stuart Walker subsequently developed a Critical Studies in Television, Volume 8, No. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

En Garde 3 50 Cents

EN GARDE 3 50 CENTS ®Z7\ ER ED THREE T-o^yneny "R/cc-er <dc-e R h a magazine of personal opinions, natter and comment - especially about Diana Rigg, Patrick MacNee and THE AVENGERS CONTENTS: TACKING ..........................an editorial .... ,pg.U by ye editor HIOFILE ON DIANA RIGG pg,? by warner bros. IROFIIE ON PATRICK MACNEE •pg.11by warner bros. THE AVENGERS ....... .a review • .......................... pg«l£ by gary crowdus TWO SEASONS - AND A HAIF ... a listing pg ,22 by ye ed TO HONOR HONOR ... .a section for honor, , pg,33 compiled by ed YOU HAVE JUST BEEN MURDERED , ,a review ........................... pg.U8 by rob firebaugh NEWS AND NOTES , , . « • .various tidbits. , • • • • pg .50 by ye editor Front Cover shows a scene from Art Credits; "The Master Minds" , 1966 show. Bacover shows sequence cut out "Walt" • , pages 11 and lb for Yankee audience. R. Schultz . , . pages 3, U, 7, 15, 18, 19,22, 35, E2, and $0 This magazine is irregularly published by: Mr, Richard Schultz, 19159 Helen, Detroit, Michigan, E823E, and: Mr. Gary Crowdus, 27 West 11th street New York City, N.Y., 10011 WELKCMMEN First off, let me apologize for the unfortunate delay in bringing out this third issue* I had already planned to bring this fount of Rigg-oriented enthusiasm out immediately after the production of #2. Like, I got delayed. Some things were added to #3, some were unfortunately dropped, some never arrived, and then I quickly came down with a cold and broke a fingernail* Have you ever tried typing stencils with a broken fingernail? Combined with the usual lethargy, this was, of course, very nearly disastrous* But, here it is* ' I hope you like it. -

8 Obituaries @Guardianobits

Section:GDN 1J PaGe:8 Edition Date:191101 Edition:01 Zone: Sent at 31/10/2019 17:49 cYanmaGentaYellowbl • The Guardian Friday 1 November 2019 [email protected] 8 Obituaries @guardianobits Birthdays want any “costume crap”. In the same anthology format – the fi rst featuring sci-fi stories – she created Rick Allen, rock Out of This World (1962). drummer, 56; Newman took Shubik with him Mark Austin, to the BBC in 1963 and she was story broadcaster, 61 ; editor on Story Parade (1964-65), Susanna Clarke, dramatisations of modern novels author, 60; Toni for the newly launched BBC2. In Collette, actor, 47; 1965, with Out of the Unknown, she Tim Cook, chief became a producer, and she stayed executive, Apple, in that role for Thirteen Against Fate 59; Sharron (1966), Hugh Leonard ’s adaptations Davies, Olympic of Georges Simenon stories. swimmer and Before switching to ITV, Shubik broadcaster, 57; worked on the BBC2 anthology Lou Donaldson, series Playhouse (1973 -76). Her alto saxophonist, commissions included half a 93; Lord (Bruce) dozen original dramas about the Grocott, Labour paranormal from writers such as politician, 79 ; Brian Hayles and Trevor. Mark Hughes, She left Granada before The Jewel football manager, in the Crown went into production 56; Jeremy Hunt, because she was asked by Columbia Conservative MP Pictures to work on the screenplay of and former health The Girl in a Swing (1988), based on seemed to “sabotage” the potential secretary, 53 ; Richard Adams ’s novel. However, it of Edna, the Inebriate Woman to Roger Kellaway, did not go beyond a fi rst draft.