Editor's Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Mouth Operations: a Swiss Case Study Michael J

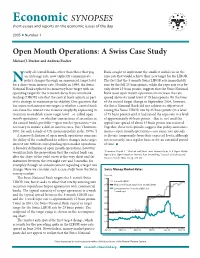

Economic SYNOPSES short essays and reports on the economic issues of the day 2005 I Number 1 Open Mouth Operations: A Swiss Case Study Michael J. Dueker and Andreas Fischer early all central banks, other than those that peg Bank sought to implement the smallest initial rise in the an exchange rate, now explicitly communicate repo rate that would achieve their new target for the LIBOR. Npolicy changes through an announced target level The fact that the 3-month Swiss LIBOR rate immediately for a short-term interest rate. Notably, in 1999, the Swiss rose by the full 25 basis points, while the repo rate rose by National Bank replaced its monetary base target with an only about 15 basis points, suggests that the Swiss National operating target for the 3-month Swiss franc interbank Bank used open mouth operations to increase the rate lending (LIBOR) rate that the central bank adjusts as part spread above its usual level of 15 basis points. By the time of its strategy to maintain price stability. One question that of the second target change in September 2004, however, has arisen with interest rate targets is whether a central bank the Swiss National Bank did not achieve its objective of can cause the interest rate to move simply by expressing its raising the Swiss LIBOR rate by 25 basis points (to a level intention to establish a new target level—so-called open of 75 basis points) until it had raised the repo rate to a level mouth operations—or whether transactions of securities in of approximately 60 basis points—that is, not until the the central bank’s portfolio—open market operations—are typical rate spread of about 15 basis points was restored. -

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990S U.S

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990s U.S. Christopher Hanes [email protected] Department of Economics SUNY-Binghamton P.O. Box 6000 Binghamton, NY 13902 July 2018 Abstract: In the 1990s it became apparent that changes in the FOMC’s target rate could be implemented through announcements alone - “open mouth operations” - without adjustments to reserve supply or the discount rate. This cannot be explained by standard models of the Fed’s system of policy implementation at the time. It differed from experience in the 1970s, the earlier era of interest-rate targeting, though the structure of implementation appeared essentially similar. I explain the appearance of open-mouth operations as a consequence of longstanding Fed discount-window lending practices, interacting with a decrease after the 1970s in the relative importance of discount borrowing by small banks. Data on discount borrowing by large versus small banks in the 1980s-1990s and the 1970s support my explanation. JEL codes E43, E51, E52, G21. Thanks to James Clouse, Selva Demiralp, Cheryl Edwards, William English, Marvin Goodfried, Kenneth Kuttner and William Whitesell. - 1 - In the 1990s Federal Reserve staff found that market overnight rates changed when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) signalled it had changed its target fed funds rate, even if the staff made no adjustment to the quantity of reserves supplied through open-market operations. Eventually the volume of bank deposits responded to interest rates through the usual “money demand” channels, and the Fed had to accommodate resulting changes in the quantity of reserves needed to satisfy fractional reserve requirements or clear payments. -

Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy

Todd Keister, Antoine Martin, and James McAndrews Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy • Many central banks operate in a way that 1.Introduction creates a tight link between money and monetary policy, as the supply of reserves onetary policy has traditionally been viewed as the must be set precisely in order to implement M process by which a central bank uses its influence over the target interest rate. the supply of money to promote its economic objectives. For example, Milton Friedman (1959, p. 24) defined the tools of • Because reserves play other key roles in the monetary policy to be those “powers that enable the [Federal economy, this link can generate tensions with Reserve] System to determine the total amount of money in central banks’ other objectives, particularly existence or to alter that amount.” In fact, the very term in periods of acute market stress. monetary policy suggests a central bank’s policy toward the supply of money or the level of some monetary aggregate. • An alternative approach to monetary policy In recent decades, however, central banks have moved away implementation can eliminate the tension from a direct focus on measures of the money supply. The between money and monetary policy primary focus of monetary policy has instead become the value by “divorcing” the quantity of reserves of a short-term interest rate. In the United States, for example, from the interest rate target. the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announces a rate that it wishes to prevail in the federal funds market, where overnight loans are made among • By paying interest on reserve balances at commercial banks. -

Expectations, Open Market Operations, and Changes in the Federal Funds

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST.LOUIS computation period. This has probably led to better Expectations, Open estimates of reserve requirements by the Trading Desk and the banks, but it has also eliminated the Market Operations, possibility of any contemporaneous response of required reserves to the interest rate. and Changes in the Another significant change made possible by computer technology is the ability of financial Federal Funds Rate institutions to efficiently “sweep” their consumers’ accounts from those with reserve requirements into John B. Taylor those without reserve requirements. These sweeps have allowed required reserve balances to decline he process through which Federal Reserve sharply from about $30 billion in 1990, to $15 bil- decisions about monetary policy are transmit- lion in 1996, to only about $5 to 6 billion today. As Tted to the federal funds market has changed a result, holding Fed balances to facilitate interbank significantly in recent years. In 1994 the Federal payments is of greater importance for many banks Open Market Committee (FOMC) began to issue than holding reserves for legal requirements. At the a public statement whenever it increased or de- same time, technology has improved the speed and creased its target for the federal funds rate. This accuracy with which banks can keep track of their target is now the focus of activities at the Trading payment inflows and outflows and thereby may Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In have reduced the demand for Fed balances.3 particular, the FOMC directs the Trading Desk to In December 1999 the FOMC further expanded buy and sell securities so that conditions in the and clarified its public announcement policy. -

New Tools for Central Bankers?

A SYMPOSIUM OF VIEWS New Tools For Central Bankers? entral banks worldwide face criticism for the inability of their policies to restore the global economy to historic levels of economic activity. CCentral bank bond buying, it is often charged, has distorted financial markets. Negative real interest rates have weakened many banking sectors. At this summer’s Jackson Hole meeting, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen proclaimed: “New policy tools, which helped the Federal Reserve respond to the financial crisis and Great Recession, are likely to remain useful in dealing with future downturns. Additional tools may be needed.” What new tools should the central bank community consider? Or has monetary policy been perceived too much as some kind of magical pill? Should fiscal and regulatory reforms come into play? THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY 220 I Street, N.E., Suite 200 Washington, D.C. 20002 More than forty noted experts share their views. Phone: 202-861-0791 Fax: 202-861-0790 www.international-economy.com [email protected] 6 THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY FALL 2016 The answer is not to transition … from the lead role in what essentially has been the equivalent of a “one-person show,” to playing a push central banks supporting role to politicians that finally step up to their economic governance responsibility and lift the con- even deeper into straints to a more comprehensive policy response. Absent such a pivot, the quest for new tools for cen- what has become an tral banks may be associated with a much more disturbing and durable development—that of seeing central banks increasingly “lose- shift from being part of the solution to becoming part of the problem. -

Monetary Policy Implementation: Misconceptions and Their Consequences by Piti Disyatat

BIS Working Papers No 269 Monetary policy implementation: Misconceptions and their consequences by Piti Disyatat Monetary and Economic Department December 2008 JEL codes: E40, E41, E51, E52, E58 Keywords: Monetary policy implementation, transmission mechanism, interest rates, money, liquidity effect, bank lending channel, sterilized intervention BIS Working Papers are written by members of the Monetary and Economic Department of the Bank for International Settlements, and from time to time by other economists, and are published by the Bank. The views expressed in them are those of their authors and not necessarily the views of the BIS. Copies of publications are available from: Bank for International Settlements Press & Communications CH-4002 Basel, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +41 61 280 9100 and +41 61 280 8100 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2008. All rights reserved. Limited extracts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISSN 1020-0959 (print) ISSN 1682-7678 (online) Abstract Despite constituting the very heart of the monetary transmission mechanism, widespread misconceptions still exist regarding how monetary policy is implemented. This paper highlights the key misconceptions in this regard and shows how they have compromised the understanding of important aspects of the monetary transmission mechanism. In particular, the misplaced emphasis on open market operations as the means through which monetary policy is implemented can give rise to inappropriate characterizations of monetary policy, as well as to ill-defined discussions of liquidity effects, the bank lending channel, and sterilized exchange rate intervention. JEL Classification: E40, E41, E51, E52, E58 Keywords: Monetary policy implementation, transmission mechanism, interest rates, money, liquidity effect, bank lending channel, sterilized intervention Monetary policy implementation: Misconceptions and their consequences iii Table of contents 1. -

Do Central Banks Control the Price Level?”

Some Thoughts on \Do Central Banks Control the Price Level?" Karl Whelan Presentation at FMM Conference School of Economics, University College Dublin October 28, 2020 Karl Whelan (UCD) Do Central Banks Control the Price Level? October 28, 2020 1 / 19 Do Central Banks Control the Price Level? An interesting question. For most of the past 40 years, the answer from most people would be \Yes ... of course". And there are loads of examples of situations where macroeconomic policy has produced (and ended) high inflation. But in recent years, central banks have failed to reach their inflation targets despite new \unconventional" monetary policies. Have central banks got the ammunition to get inflation back to their desired levels? My (two handed ...) answer: 1 Yes but current conventions (and current conditions) constrain them from taking the necessary actions. 2 But this doesn't matter because we can use fiscal policy instead. Karl Whelan (UCD) Do Central Banks Control the Price Level? October 28, 2020 2 / 19 Roadmap for the Talk 1 Micro price theory versus macro price theory 2 Why central banks? I Monetarism I The Phillips curve I Central bank independence 3 The current situation I Low equilibrium real interest rates and unconventional policies. I Helicopter drops? I Fiscal policy options Karl Whelan (UCD) Do Central Banks Control the Price Level? October 28, 2020 3 / 19 Micro Pricing Evidence versus Macro Confusion The price level is just an aggregation of loads of individual prices. Empirical microeconomics is an extremely successful discipline and is very good at explaining prices. Study after study confirms that prices are a function of 1 Demand 2 Supply 3 Market structure Changing market structures may play some role in determining the aggregate price level but for the economy of the whole, it is reasonable to asset that the dominant factor driving prices is the demand for goods and services and the capacity to supply them. -

Nber Working Paper Series Monetary Policy in the Information Economy

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES MONETARY POLICY IN THE INFORMATION ECONOMY Michael Woodford Working Paper 8674 http://www.nber.org/papers/w8674 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2001 Prepared for the “Symposium on Economic Policy for the Information Economy,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 30-September 1, 2001. I am especially grateful to Andy Brookes (RBNZ), Chuck Freedman (Bank of Canada), and Chris Ryan (RBA) for their unstinting efforts to educate me about the implementation of monetary policy at their respective central banks. Of course, none of them should be held responsible for the interpretations offered here. I would also like to thank David Archer, Alan Blinder, Kevin Clinton, Ben Friedman, David Gruen, Bob Hall, Spence Hilton, Mervyn King, Ken Kuttner, Larry Meyer, Hermann Remsperger, Lars Svensson, Bruce White and Julian Wright for helpful discussions, Gauti Eggertsson and Hong Li for research assistance, and the National Science Foundation for research support through a grant to the National Bureau of Economic Research. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. © 2001 by Michael Woodford. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Monetary Policy in the Information Economy Michael Woodford NBER Working Paper No. 8674 December 2001 JEL No. E58 ABSTRACT This paper considers two challenges that improvements in private-sector information-processing capabilities may pose for the effectiveness of monetary policy. -

Odyssean Forward Guidance in Monetary Policy: a Primer

Odyssean forward guidance in monetary policy: A primer Jeffrey R. Campbell Introduction and summary with making its internal decision-making process The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) more transparent and therefore more forecastable. In monetary policy statement from its September 2013 this, they followed several foreign central banks that meeting reads in part: had already adopted explicit inflation targets. (See Bernanke and Woodford, 2005, for a review of inflation In particular, the Committee decided to keep targeting and its implementation outside the United the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to States.) The financial crisis dramatically accelerated 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this ex- the transition to greater openness, and the FOMC’s ceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unem- ployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, infla- Jeffrey R. Campbell is a senior economist and research advisor tion between one and two years ahead is projected in the Economic Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and an external fellow at CentER, Tilburg to be no more than a half percentage point above University. The author is grateful to Marco Bassetto, Charlie the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and Evans, Jonas Fisher, Alejandro Justiniano, and Spencer Krane for many stimulating discussions on forward guidance and to longer-term inflation expectations continue to be Wouter den Haan, Alejandro Justiniano, and Dick Porter for well anchored.1 helpful editorial feedback. This article is being concurrently published in Wouter den Haan (ed.), 2013, Forward Guidance— This extended reference to the conditions deter- Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market mining the FOMC’s future interest rate decisions is Participants, Centre for Economic Policy Research, VoxEU.org. -

Equilibrium Uniqueness and Forward Guidance with Inconsistent Optimal Plans

Discretion Rather than Rules: Equilibrium Uniqueness and Forward Guidance with Inconsistent Optimal Plans Jeffrey R. Campbell and Jacob P. Weber REVISED January 31, 2019 WP 2018-14 https://doi.org/10.21033/wp-2018-14 *Working papers are not edited, and all opinions and errors are the responsibility of the author(s). The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Reserve Federal Reserve System. Discretion Rather than Rules: Equilibrium Uniqueness and Forward Guidance with Inconsistent Optimal Plans Jeffrey R. Campbell∗ Jacob P. Webery January 31, 2019 Abstract New Keynesian economies with active interest rate rules gain equilibrium deter- minacy from the central bank's incredible off-equilibrium-path promises (Cochrane, 2011). We suppose instead that the central bank sets interest rate paths and occa- sionally has the discretion to change them. With empirically-reasonable frequencies of central bank reoptimization, the monetary policy game has a unique Markov-perfect equilibrium wherein forward guidance influences current outcomes without displaying a forward guidance puzzle. ∗Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and CentER, Tilburg University. Jeff[email protected] yDepartment of Economics, University of California at Berkeley. jacob [email protected] We thank Roc Armenter, Gadi Barlevy, Bob Barsky, Marco Bassetto, Gauti Eggertsson, Jordi Gal´ı, Si- mon Gilchrist, the late Alejandro Justiniano, Assaf Patir, Stephanie Schmitt-Groh´e,Johannes Wieland and Michael Yang for insightful comments and discussion. Any errors that remain are our own. The views expressed herein are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, the Federal Reserve System, or its Board of Governors. -

The Grammar of Money an Analytical Account of Money As a Discursive Institution in Light of the Practice of Complementary Currencies

The Grammar of Money An Analytical Account of Money as a Discursive Institution in Light of the Practice of Complementary Currencies Leander Bindewald, MSc. (Diplombiologe), M.A. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate School University of Cumbria and Lancaster University Lancaster, September 2018 Wordcount: 79,970 Abstract Since the global financial crisis in 2008, complementary currencies - from local initiatives like the Brixton Pound to timebanks, business-to-business currencies and, of course, Bitcoin - have received unprecedented attention by academics, policy makers, the media and the general public. However, at close theoretic inspection money itself remains as elusive a phenomenon as water must be to fish. Economic and business disciplines commonly only describe the use and functionality of money rather than its nature. Sociology and philosophy have a more fundamental set of approaches, but remain largely unintegrated in financial policy and common perception. At the same time, new forms of currency challenge predominant definitions of money and their implementation in the law and financial regulation. Unless our understanding of money and currencies is questioned and extended to consistently reflect theory and practice, its current misalignment threatens to impede much needed reform and innovation of the financial systems towards equity, democratic participation and sustainability. After reviewing current monetary theories and their epistemological underpinning, this thesis proposes a new theoretic framework of money as a ‘discursive institution’ that can be applied coherently to all monetary phenomena, conventional and unconventional. It also allows for the empirical analysis of currencies with the methodologies of neo-institutionalism, practice theory and critical discourse analysis. -

Ben Bernanke,” Real Time Economics (Blog), November 15Th 2010

MONETARY POLICY IN A NEW ERA Ben S. Bernanke Brookings Institution October 2, 2017 Prepared for conference on Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy, Peterson Institute, Washington DC, October 12-13, 2017. The author is a Distinguished Fellow at the Brookings Institution and the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy. I thank Olivier Blanchard, Donald Kohn, and David Wessel for comments and Michael Ng for excellent research assistance. In 2017, the flagship research conferences of the European Central Bank and the Federal Reserve—held in Sintra, Portugal, and Jackson Hole, Wyoming, respectively—had something in common: Both had official themes unrelated to monetary policy, or even central banking. The ECB conference (theme: Investment and Growth in Advanced Economies) did include an opening speech by President Mario Draghi on monetary policy and the outlook, before turning to issues like the prospective effects of technological advances on employment. However, the Fed’s meeting (theme: Fostering a Dynamic Global Economy), which included papers on topics ranging from fiscal policy to trade to income distribution, made almost no mention of monetary policy. Whether intended or not, the signal, I think, was clear. After ten years of concerted effort first to restore financial stability, then to achieve economic recovery through dramatic monetary interventions, central bankers in Europe and the United States believe that they see the light at the end of the tunnel. They are looking forward to an era of relative financial and economic stability in which the pressing economic issues will relate to growth, globalization, and distribution—issues that are the responsibility of other policymakers and not primarily the province of central bankers.