The Relationship Between the Federal Funds Rate and the Fed's Federal Funds Rate Target: Is It Open Market Or Open Mouth Operations?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FOMC Statement

For release at 2 p.m. EDT July 28, 2021 The Federal Reserve is committed to using its full range of tools to support the U.S. economy in this challenging time, thereby promoting its maximum employment and price stability goals. With progress on vaccinations and strong policy support, indicators of economic activity and employment have continued to strengthen. The sectors most adversely affected by the pandemic have shown improvement but have not fully recovered. Inflation has risen, largely reflecting transitory factors. Overall financial conditions remain accommodative, in part reflecting policy measures to support the economy and the flow of credit to U.S. households and businesses. The path of the economy continues to depend on the course of the virus. Progress on vaccinations will likely continue to reduce the effects of the public health crisis on the economy, but risks to the economic outlook remain. The Committee seeks to achieve maximum employment and inflation at the rate of 2 percent over the longer run. With inflation having run persistently below this longer-run goal, the Committee will aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time so that inflation averages 2 percent over time and longer‑term inflation expectations remain well anchored at 2 percent. The Committee expects to maintain an accommodative stance of monetary policy until these outcomes are achieved. The Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and expects it will be appropriate to maintain this target range until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessments of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on (more) For release at 2 p.m. -

Open Mouth Operations: a Swiss Case Study Michael J

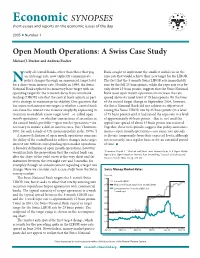

Economic SYNOPSES short essays and reports on the economic issues of the day 2005 I Number 1 Open Mouth Operations: A Swiss Case Study Michael J. Dueker and Andreas Fischer early all central banks, other than those that peg Bank sought to implement the smallest initial rise in the an exchange rate, now explicitly communicate repo rate that would achieve their new target for the LIBOR. Npolicy changes through an announced target level The fact that the 3-month Swiss LIBOR rate immediately for a short-term interest rate. Notably, in 1999, the Swiss rose by the full 25 basis points, while the repo rate rose by National Bank replaced its monetary base target with an only about 15 basis points, suggests that the Swiss National operating target for the 3-month Swiss franc interbank Bank used open mouth operations to increase the rate lending (LIBOR) rate that the central bank adjusts as part spread above its usual level of 15 basis points. By the time of its strategy to maintain price stability. One question that of the second target change in September 2004, however, has arisen with interest rate targets is whether a central bank the Swiss National Bank did not achieve its objective of can cause the interest rate to move simply by expressing its raising the Swiss LIBOR rate by 25 basis points (to a level intention to establish a new target level—so-called open of 75 basis points) until it had raised the repo rate to a level mouth operations—or whether transactions of securities in of approximately 60 basis points—that is, not until the the central bank’s portfolio—open market operations—are typical rate spread of about 15 basis points was restored. -

Recent Monetary Policy in the US

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons School of Business: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 6-2005 Recent Monetary Policy in the U.S.: Risk Management of Asset Bubbles Anastasios G. Malliaris Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Marc D. Hayford Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/business_facpubs Part of the Business Commons Author Manuscript This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Recommended Citation Malliaris, Anastasios G. and Hayford, Marc D.. Recent Monetary Policy in the U.S.: Risk Management of Asset Bubbles. The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, 2, 1: 25-39, 2005. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, School of Business: Faculty Publications and Other Works, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.jeca.2005.01.002 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Business: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © Elsevier B. V. 2005 Recent Monetary Policy in the U.S.: Risk Management of Asset Bubbles Marc D. Hayford Loyola University Chicago A.G. Malliaris1 Loyola University Chicago Abstract: Recently Chairman Greenspan (2003 and 2004) has discussed a risk management approach to the implementation of monetary policy. This paper explores the economic environment of the 1990s and the policy dilemmas the Fed faced given the stock boom from the mid to late 1990s to after the bust in 2000-2001. -

Greenspan's Conundrum and the Fed's Ability to Affect Long-Term

Research Division Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Paper Series Greenspan’s Conundrum and the Fed’s Ability to Affect Long- Term Yields Daniel L. Thornton Working Paper 2012-036A http://research.stlouisfed.org/wp/2012/2012-036.pdf September 2012 FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS Research Division P.O. Box 442 St. Louis, MO 63166 ______________________________________________________________________________________ The views expressed are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, the Federal Reserve System, or the Board of Governors. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comment. References in publications to Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Working Papers (other than an acknowledgment that the writer has had access to unpublished material) should be cleared with the author or authors. Greenspan’s Conundrum and the Fed’s Ability to Affect Long-Term Yields Daniel L. Thornton Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Phone (314) 444-8582 FAX (314) 444-8731 Email Address: [email protected] August 2012 Abstract In February 2005 Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan noticed that the 10-year Treasury yields failed to increase despite a 150-basis-point increase in the federal funds rate as a “conundrum.” This paper shows that the connection between the 10-year yield and the federal funds rate was severed in the late 1980s, well in advance of Greenspan’s observation. The paper hypothesize that the change occurred because the Federal Open Market Committee switched from using the federal funds rate as an operating instrument to using it to implement monetary policy and presents evidence from a variety of sources supporting the hypothesis. -

FEDERAL FUNDS Marvin Goodfriend and William Whelpley

Page 7 The information in this chapter was last updated in 1993. Since the money market evolves very rapidly, recent developments may have superseded some of the content of this chapter. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond Richmond, Virginia 1998 Chapter 2 FEDERAL FUNDS Marvin Goodfriend and William Whelpley Federal funds are the heart of the money market in the sense that they are the core of the overnight market for credit in the United States. Moreover, current and expected interest rates on federal funds are the basic rates to which all other money market rates are anchored. Understanding the federal funds market requires, above all, recognizing that its general character has been shaped by Federal Reserve policy. From the beginning, Federal Reserve regulatory rulings have encouraged the market's growth. Equally important, the federal funds rate has been a key monetary policy instrument. This chapter explains federal funds as a credit instrument, the funds rate as an instrument of monetary policy, and the funds market itself as an instrument of regulatory policy. CHARACTERISTICS OF FEDERAL FUNDS Three features taken together distinguish federal funds from other money market instruments. First, they are short-term borrowings of immediately available money—funds which can be transferred between depository institutions within a single business day. In 1991, nearly three-quarters of federal funds were overnight borrowings. The remainder were longer maturity borrowings known as term federal funds. Second, federal funds can be borrowed by only those depository institutions that are required by the Monetary Control Act of 1980 to hold reserves with Federal Reserve Banks. -

U.S. Policy in the Bretton Woods Era I

54 I Allan H. Meltzer Allan H. Meltzer is a professor of political economy and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University and is a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. This paper; the fifth annual Homer Jones Memorial Lecture, was delivered at Washington University in St. Louis on April 8, 1991. Jeffrey Liang provided assistance in preparing this paper The views expressed in this paper are those of Mr Meltzer and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve System or the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. U.S. Policy in the Bretton Woods Era I T IS A SPECIAL PLEASURE for me to give world now rely on when they want to know the Homer Jones lecture before this distinguish- what has happened to monetary growth and ed audience, many of them Homer’s friends. the growth of other non-monetary aggregates. 1 am persuaded that the publication and wide I I first met Homer in 1964 when he invited me dissemination of these facts in the 1960s and to give a seminar at the Bank. At the time, I was 1970s did much more to get the monetarist case a visiting professor at the University of Chicago, accepted than we usually recognize. 1 don’t think I on leave from Carnegie-Mellon. Karl Brunner Homer was surprised at that outcome. He be- and I had just completed a study of the Federal lieved in the power of ideas, but he believed Reserve’s monetary policy operations for Con- that ideas were made powerful by their cor- gressman Patman’s House Banking Committee. -

The Discount Window Refers to Lending by Each of Accounts” on the Liability Side

THE DISCOUNT -WINDOW David L. Mengle The discount window refers to lending by each of Accounts” on the liability side. This set of balance the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks to deposi- sheet entries takes place in all the examples given in tory institutions. Discount window loans generally the Box. fund only a small part of bank reserves: For ex- The next day, Ralph’s Bank could raise the funds ample, at the end of 1985 discount window loans to repay the loan by, for example, increasing deposits were less than three percent of total reserves. Never- by $1,000,000 or by selling $l,000,000 of securities. theless, the window is perceived as an important tool In either case, the proceeds initially increase reserves. both for reserve adjustment and as part of current Actual repayment occurs when Ralph’s Bank’s re- Federal Reserve monetary control procedures. serve account is debited for $l,000,000, which erases the corresponding entries on Ralph’s liability side and Mechanics of a Discount Window Transaction on the Reserve Bank’s asset side. Discount window lending takes place through the Discount window loans, which are granted to insti- reserve accounts depository institutions are required tutions by their district Federal Reserve Banks, can to maintain at their Federal Reserve Banks. In other be either advances or discounts. Virtually all loans words, banks borrow reserves at the discount win- today are advances, meaning they are simply loans dow. This is illustrated in balance sheet form in secured by approved collateral and paid back with Figure 1. -

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990S U.S

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990s U.S. Christopher Hanes [email protected] Department of Economics SUNY-Binghamton P.O. Box 6000 Binghamton, NY 13902 July 2018 Abstract: In the 1990s it became apparent that changes in the FOMC’s target rate could be implemented through announcements alone - “open mouth operations” - without adjustments to reserve supply or the discount rate. This cannot be explained by standard models of the Fed’s system of policy implementation at the time. It differed from experience in the 1970s, the earlier era of interest-rate targeting, though the structure of implementation appeared essentially similar. I explain the appearance of open-mouth operations as a consequence of longstanding Fed discount-window lending practices, interacting with a decrease after the 1970s in the relative importance of discount borrowing by small banks. Data on discount borrowing by large versus small banks in the 1980s-1990s and the 1970s support my explanation. JEL codes E43, E51, E52, G21. Thanks to James Clouse, Selva Demiralp, Cheryl Edwards, William English, Marvin Goodfried, Kenneth Kuttner and William Whitesell. - 1 - In the 1990s Federal Reserve staff found that market overnight rates changed when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) signalled it had changed its target fed funds rate, even if the staff made no adjustment to the quantity of reserves supplied through open-market operations. Eventually the volume of bank deposits responded to interest rates through the usual “money demand” channels, and the Fed had to accommodate resulting changes in the quantity of reserves needed to satisfy fractional reserve requirements or clear payments. -

Monetary Policy Report, February 19, 2021

For use at 11:00 a.m. EST February 19, 2021 MONETARY POLICY REPORT February 19, 2021 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Washington, D.C., February 19, 2021 The President of the Senate The Speaker of the House of Representatives The Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report pursuant to section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act. Sincerely, Jerome H. Powell, Chair STATEMENT ON LONGER-RUN GOALS AND MONETARY POLICY STRATEGY Adopted effective January 24, 2012; as amended effective January 26, 2021 The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is firmly committed to fulfilling its statutory mandate from the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public as clearly as possible. Such clarity facilitates well-informed decisionmaking by households and businesses, reduces economic and financial uncertainty, increases the effectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability, which are essential in a democratic society. Employment, inflation, and long-term interest rates fluctuate over time in response to economic and financial disturbances. Monetary policy plays an important role in stabilizing the economy in response to these disturbances. The Committee’s primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy is through changes in the target range for the federal funds rate. The Committee judges that the level of the federal funds rate consistent with maximum employment and price stability over the longer run has declined relative to its historical average. -

Lecture Guide: How the Federal Reserve Implements Monetary Policy

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST. LOUIS ECONOMIC EDUCATION Lecture Guide: How the Federal Reserve Implements Monetary Policy Lesson Authors Jane Ihrig, Ph.D., Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System Scott Wolla, Ph.D., Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Standards and Benchmarks (see page 24) Lesson Description The Federal Reserve (Fed) is the central bank of the United States. Its congressionally mandated objectives are to promote maximum employment and price stability. This lesson focuses on how the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) conducts monetary policy to achieve this dual mandate. The discussion begins by tracing out the transmission of monetary policy from the FOMC’s setting of its policy interest rate target to market interest rates and, ultimately, employ- ment and inflation outcomes. Students then learn about the tools the Fed uses to ensure that market interest rates are aligned with the FOMC’s target interest rate. The economic concepts of reservation rate and arbitrage are taught. Finally, examples of how the FOMC responds to various economic shocks are presented to reinforce the key concepts covered in this lesson. Grade Level High School or College Concepts Administered rates Inflation Arbitrage Interest on reserve balances Contractionary monetary policy Maximum employment Discount rate Monetary policy Dual mandate Open market operations Expansionary monetary policy Overnight reverse repurchase agreement offering rate Federal funds rate Price stability Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) Reservation rate Federal Reserve System Reserve balance accounts ©2021, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Permission is granted to reprint or photocopy this lesson in its entirety for educational purposes, provided the user credits the Federal Reserve Bank of St. -

How Did the Fed Funds Market Change When Excess Reserves Were Abundant? John P

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF NEW YORK ECONOMIC POLICY REVIEW SHORTER ARTICLE How Did the Fed Funds Market Change When Excess Reserves Were Abundant? John P. McGowan and Ed Nosal Volume 26, Number 1 March 2020 How Did the Fed Funds Market Change When Excess Reserves Were Abundant? John P. McGowan and Ed Nosal OVERVIEW he Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) uses • The authors compare the Tthe federal funds rate as its policy rate to convey the Federal Reserve’s monetary stance of monetary policy, and has done so for decades. policy framework pre-crisis, Nominal changes in the rate are expected to be transmitted when reserves were scarce, with its framework post-crisis broadly to other financial markets to have the desired effect through early 2018, when on overall employment and inflation expectations in the reserves were abundant, and United States. analyze the related changes in Prior to the 2007 financial crisis, trading in the fed funds the federal funds market. market was dominated by banks.1 Banks managed the bal- • Pre-crisis, the fed funds ances—or reserves—of their Federal Reserve accounts by market was active and banks buying these balances from, or selling them to, each other. were the key participants. No These exchanges between holders of reserve balances at the Fed interest was paid on reserves are known as fed funds transactions. The amount of excess and the effective fed funds rate (EFFR) typically exhibited reserves in the banking system—total reserves minus total some day-to-day volatility. required reserves—was very small and banks actively traded Post-crisis, fed funds market fed funds in order to keep their reserves close to the required activity declined and foreign amount. -

FOMC Meeting Minutes

A meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee was held in the offices of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in Washington on Tuesday, June 20, 1961, at 10:00 a.m. PRESENT: Mr. Martin, Chairman Mr. Allen Mr. Balderston Mr. Mills Mr. Robertson Mr. Shepardson Mr. Swan Mr. Wayne Mr. Johns, Alternate for Mr. Irons Mr. Treiber, Alternate for Mr. Hayes Messrs. Ellis, Fulton, and Deming, Alternate Members of the Federal Open Market Committee Messrs. Bopp, Bryan, and Clay, Presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia, Atlanta, and Kansas City, respectively Mr. Young, Secretary Mr. Sherman, Assistant Secretary Mr. Kenyon, Assistant Secretary Mr. Hexter, Assistant General Counsel Mr. Thomas, Economist Messrs. Coldwell, Einzig, Garvy, Noyes, and Ratchford, Associate Economists Mr. Rouse, Manager, System Open Market Account Mr. Molony, Assistant to the Board of Governors Mr. Koch, Adviser, Division of Research and Statistics, Board of Governors Mr. Knipe, Consultant to the Chairman, Board of Governors Mr. Yager, Economist, Government Finance Section, Division of Research and Statistics, Board of Governors Mr. Petersen, Special Assistant, Office of the Secretary Mr. Hickman, Senior Vice President, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland 6/20/61 -2 Messrs. Eastburn, Baughman, and Tow, Vice Presidents of the Federal Reserve Banks of Philadelphia, Chicago, and Kansas City, respectively Mr. Holmes, Manager, Securities Department, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Messrs. Bowsher and Hellweg, Economists, Federal Reserve Banks of St. Louis and Minneapolis, respectively. Chairman Martin noted that consideration of approval of the minutes of the Committee meeting on May 9, 1961, had been deferred at the June 6 meeting in order that the Committee members might have an opportunity to study certain comments of Mr.