Identifying Monetary Policy Shocks with Changes in Open Market Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finance Without Financiers*

3 Finance without Financiers* Robert C. Hockett, Cornell Law School * Thanks to Dan Alpert, Fadhel Kaboub, Stephanie Kelton, Paul McCulley, Zoltan Polszar, Nouriel Roubini and particularly my alter ego Saule Omarova. Special thanks to Fred Block and Erik Olin Wright, who have been part of this project since its inception in 2014 – as well as to the “September Group,” where it proved necessary that same year to formulate arguments whose full elaboration has issued in this Chapter. Hockett, Finance without Financiers 4 I see, therefore, the rentier aspect of capitalism as a transitional phase which will disappear when it has done its work…Thus [we] might aim in practice… at an increase in the volume of capital until it ceases to be scarce, so that the functionless investor will no longer receive a bonus; and at a scheme of direct taxation which allows the intelligence and determination and executive skill of the financiers… (who are certainly so fond of their craft that their labour could be obtained much cheaper than at present), to be harnessed to the service of the community on reasonable terms of reward.1 INTRODUCTION: MYTHS OF SCARCITY AND INTERMEDIATION A familiar belief about banks and other financial institutions is that they function primarily as “intermediaries,” managing flows of scarce funds from private sector “savers” or “surplus units” who have accumulated them to “dissevers” or “deficit units” who have need of them and can pay for their use. This view is routinely stated in treatises,2 textbooks,3 learned journals,4 and the popular media.5 It also lurks in the background each time we hear theoretical references to “loanable funds,” practical warnings about public “crowd-out” of private investment, or the like.6 This, what I shall call “intermediated scarce private capital” view of finance bears two interesting properties. -

COVID-19 Activity in U.S. Public Finance

COVID-19COVID-19 ActivityActivity InIn U.S.U.S. PublicPublic FinanceFinance JulyJuly 22,22, 20212021 Rating Activity PRIMARY CREDIT ANALYST On Sept. 22, 2020, we changed the presentation of rating changes in the summary table below. For Robin L Prunty issuers that have had multiple rating actions since March 24, 2020, the table now shows the most New York recent rating action rather than the first. Each issuer will only be included in the summary table + 1 (212) 438 2081 once. robin.prunty @spglobal.com SECONDARY CONTACT Summary Of Rating Actions Eden P Perry Through July 21, 2021 New York (1) 212-438-0613 On Sept. 22, 2020, we changed the presentation of rating changes in the summary table below. For issuers that have had multiple rating eden.perry actions since March 24, 2020, the table now shows the most recent rating action rather than the first. Each issuer will only be included in @spglobal.com the summary table once. Charter Schs, Independent Schs, Health Higher Ed & Community Local Action Care Housing Not-For-Profit Colls Govts States Transportation Utilities Total Downgrade 9 12 28 3 39 2 6 4 103 Downgrade + 1 2 1 4 CreditWatch negative Downgrade + 4 1 10 2 24 2 5 48 Negative outlook revision Downgrade + 3 2 5 Off CreditWatch Downgrade + 10 1 16 3 36 1 1 68 Stable outlook revision Negative 39 13 169 20 525 14 44 28 852 outlook revision Stable 21 1 71 1 330 11 142 5 582 outlook revision www.spglobal.com/ratings July 22, 2021 1 COVID-19 Activity In U.S. -

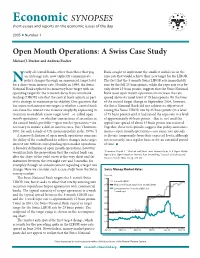

Open Mouth Operations: a Swiss Case Study Michael J

Economic SYNOPSES short essays and reports on the economic issues of the day 2005 I Number 1 Open Mouth Operations: A Swiss Case Study Michael J. Dueker and Andreas Fischer early all central banks, other than those that peg Bank sought to implement the smallest initial rise in the an exchange rate, now explicitly communicate repo rate that would achieve their new target for the LIBOR. Npolicy changes through an announced target level The fact that the 3-month Swiss LIBOR rate immediately for a short-term interest rate. Notably, in 1999, the Swiss rose by the full 25 basis points, while the repo rate rose by National Bank replaced its monetary base target with an only about 15 basis points, suggests that the Swiss National operating target for the 3-month Swiss franc interbank Bank used open mouth operations to increase the rate lending (LIBOR) rate that the central bank adjusts as part spread above its usual level of 15 basis points. By the time of its strategy to maintain price stability. One question that of the second target change in September 2004, however, has arisen with interest rate targets is whether a central bank the Swiss National Bank did not achieve its objective of can cause the interest rate to move simply by expressing its raising the Swiss LIBOR rate by 25 basis points (to a level intention to establish a new target level—so-called open of 75 basis points) until it had raised the repo rate to a level mouth operations—or whether transactions of securities in of approximately 60 basis points—that is, not until the the central bank’s portfolio—open market operations—are typical rate spread of about 15 basis points was restored. -

Guidelines for Public Financial Management Reform

Commonwealth Secretariat Published by: Commonwealth Secretariat Marlborough House Pall Mall London SW1Y 5HX United Kingdom Copyright @ Commonwealth Secretariat All Rights Reserved. No part of this public publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. May be purchased from Publication Unit Commonwealth Secretariat Telephone: +44(0)20 7747 6342 Facsimile: +44(0)20 7839 9081 GUIDELINES FOR PUBLIC FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT REFORM Commonwealth Secretariat TABLE OF CONTENTS Reform 26 Appendix C List of Participants of the Brainstorming Workshop 34 FOREWORD v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. PROCESS FRAMEWORK (“HOW”) 3 2.1. Develop a strategic reform framework 3 2.2. Address structural issues 4 2.3. Make a commitment to change (political will) 5 2.4. Establish and empower key institutions 7 2.5. Managing reform 7 2.6. Monitor progress of PFM reforms 10 3. FISCAL FRAMEWORK (“WHAT”) 12 3.1. Revenue collection 12 3.2. Improve debt management 13 3.3. Improve planning processes 14 3.4. Improve budgeting 14 3.5. Strong budget implementation, accounting and reporting 15 3.6. Procurement 16 3.7. Strong internal and external oversight 17 4. Conclusion 22 References 23 Appendix A: Excerpts from the Abuja Communique 2003 24 iv Appendix B: Supporting Better Country Public Financial Management Systems: Towards a Strengthened Approach to Supporting PFR FOREWORD ABBREVIATIONS ANAO Australia National Audit Office Implementing the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) demands effective public ANC African National Congress financial management that is imbued with transparency and accountability measures to CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment achieve strategic outcomes. -

Public Finance Authority

PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED MAY 31, 2018 NEW ISSUE RATING: Fitch: BB BOOK-ENTRY ONLY In the opinion of Womble Bond Dickinson (US) LLP, Bond Counsel, under existing law and assuming continuing compliance by the Authority and the Corporation with their respective covenants to comply with the requirements of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Code”), as described herein, interest on the Bonds will not be includable in the gross income of the owners thereof for purposes of federal income taxation. Bond Counsel is also of the opinion that interest on the Bonds will not be a specific preference item for purposes of the alternative minimum tax imposed by the Code. Interest on the Bonds will not be exempt from State of Wisconsin or State of North Carolina income taxes. See “TAX TREATMENT.” $91,460,000* PUBLIC FINANCE AUTHORITY RETIREMENT FACILITIES FIRST MORTGAGE REVENUE BONDS (SOUTHMINSTER) SERIES 2018 Dated: Date of Delivery Due: As shown on inside front cover The Bonds offered hereby (the “Bonds”) are being issued by the Public Finance Authority (the “Authority”) pursuant to a Trust Agreement between the Authority and The Bank of New York Mellon Trust Company, N.A., as trustee (the “Bond Trustee”), for the purpose of providing funds to Southminster, Inc. (the “Corporation”), to be used, together with other available funds, to (i) pay the costs of the Project (as defined herein), (ii) fund Reserve Fund No. 1 (as defined herein) and (iii) pay certain expenses incurred in connection with the issuance of the Bonds. See “THE PROJECT” in Appendix A hereto and “SECURITY AND SOURCES OF PAYMENT FOR THE BONDS” herein. -

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990S U.S

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990s U.S. Christopher Hanes [email protected] Department of Economics SUNY-Binghamton P.O. Box 6000 Binghamton, NY 13902 July 2018 Abstract: In the 1990s it became apparent that changes in the FOMC’s target rate could be implemented through announcements alone - “open mouth operations” - without adjustments to reserve supply or the discount rate. This cannot be explained by standard models of the Fed’s system of policy implementation at the time. It differed from experience in the 1970s, the earlier era of interest-rate targeting, though the structure of implementation appeared essentially similar. I explain the appearance of open-mouth operations as a consequence of longstanding Fed discount-window lending practices, interacting with a decrease after the 1970s in the relative importance of discount borrowing by small banks. Data on discount borrowing by large versus small banks in the 1980s-1990s and the 1970s support my explanation. JEL codes E43, E51, E52, G21. Thanks to James Clouse, Selva Demiralp, Cheryl Edwards, William English, Marvin Goodfried, Kenneth Kuttner and William Whitesell. - 1 - In the 1990s Federal Reserve staff found that market overnight rates changed when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) signalled it had changed its target fed funds rate, even if the staff made no adjustment to the quantity of reserves supplied through open-market operations. Eventually the volume of bank deposits responded to interest rates through the usual “money demand” channels, and the Fed had to accommodate resulting changes in the quantity of reserves needed to satisfy fractional reserve requirements or clear payments. -

Public Money for the Public Good

ICAEW BETTER GOVERNMENT SERIES Public money for the public good BUILDING TRUST IN THE PUBLIC FINANCES A POLICY INSIGHT PUBLIC MONEY FOR THE PUBLIC GOOD PUBLIC MONEY FOR THE PUBLIC GOOD PageForeword head ‘Public money ought to be For the government this bond of trust is INSIGHT especially important. The public needs to With the public touched with the most trust that when the government asks them for sector making scrupulous conscientiousness taxes, the monies paid over and other public up nearly half resources will be used for the public good. of the global of honour. It is not the economy, effective public financial produce of riches only, but Every country has a unique history and faces management is a of the hard earnings of distinct challenges. While there can never critical factor in the be a single approach to public financial economic success labour and poverty.’ management, there are certain universal of each and principles and factors which underpin the every country. Thomas Paine creation of trust anywhere in the world. This publication provides an overview of those Successful economies deliver sustainable factors, both cultural and technical. growth and resources to meet the needs of individuals, communities and business. With To illustrate what can be done, we have government activities accounting for nearly half included a range of case studies showing of the global economy, effective public financial how different countries have taken practical management is a crucial, yet all too often steps to build trust in public money. The overlooked, condition for prosperity. majority of these are from developing nations: lower GDP is no barrier to effective public The role of professional accountants is financial management. -

Public Finance Overview

Jim Young, Esq. and Warren Greenlee, Esq. Young Law Group, PLLC 601.354.3660 [email protected] [email protected] Debt must comply with statutes • Purpose for borrowing • Process of borrowing • Structure of debt • Investment of proceeds Failure to comply can lead to jail and fines Public Finance is highly regulated State and local issues Federal tax • Amount of issue • Timing of issue • Use of proceeds • Use of project • Arbitrage rebate Federal securities law • Initial offering disclosure • Continuing disclosure • General anti-fraud provisions • Method of sale/Necessary parties These days you have to create your own breaks • Strategic planning • Millage management • Efficiencies and savings • Refundings • Cooperative endeavors • Operational savings It is not rocket science One size does not fit all Options for structure Options for method of sale MAS Small Loan Program Options for issuer vs. conduit Options for finance team Parties Involved in Financing Bond Counsel (hired by county to give legal opinion) County has met all legal & procedural requirements Interest on debt is exempt Generally prepares authorizing resolutions & closing documents Issuer’s Counsel (county attorney) Gives legal opinion that the authorizing resolutions & closing documents were validly approved by county Assists bond counsel with local matters Financial Advisor (Municipal Advisor) – assists county on financial matters in connection with issuing debt Method of sale (competitive bid, negotiated, underwritten, private placement, direct bank loan) Sizing & structuring -

The Top 10 Management Characteristics of Highly Rated U.S

The Top 10 Management Characteristics Of Highly Rated U.S. Public Finance Issuers Primary Credit Analyst: John A Sugden, New York (1) 212-438-1678; [email protected] Secondary Contact: Robin L Prunty, New York (1) 212-438-2081; [email protected] Table Of Contents Top 10 List WWW.STANDARDANDPOORS.COM/RATINGSDIRECT JULY 23, 2012 1 1001327 | 300126912 The Top 10 Management Characteristics Of Highly Rated U.S. Public Finance Issuers (Editor's Note: This is an updated version of an article published July 26, 2010.) U.S. public finance issuers are a varied group, but the management practices of the strongest borrowers show some distinct commonalities. Standard & Poor's Ratings Services has widely disseminated to investors and issuers its approach for assigning credit ratings in U.S. public finance (see "USPF Criteria: State Ratings Methodology," published Jan. 3, 2011; and "USPF Criteria: GO Debt," published Oct. 12, 2006, on RatingsDirect on the Global Credit Portal). We have also developed representative ranges for key ratios that factor into our analysis of tax-backed credit quality (see "USPF Criteria: Key General Obligation Ratio Credit Ranges – Analysis Vs. Reality," published April 2, 2008). Although these ratios are the foundation of the quantitative measures Standard & Poor's uses when assigning a credit rating, Standard & Poor's also relies on qualitative factors to inform our credit analysis. In 2006, Standard & Poor's released its Financial Management Assessment, which offers a more transparent assessment of a government's financial practices, as an integral part of our credit rating process (see "Financial Management Assessment," published June 27, 2006). -

Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy

Todd Keister, Antoine Martin, and James McAndrews Divorcing Money from Monetary Policy • Many central banks operate in a way that 1.Introduction creates a tight link between money and monetary policy, as the supply of reserves onetary policy has traditionally been viewed as the must be set precisely in order to implement M process by which a central bank uses its influence over the target interest rate. the supply of money to promote its economic objectives. For example, Milton Friedman (1959, p. 24) defined the tools of • Because reserves play other key roles in the monetary policy to be those “powers that enable the [Federal economy, this link can generate tensions with Reserve] System to determine the total amount of money in central banks’ other objectives, particularly existence or to alter that amount.” In fact, the very term in periods of acute market stress. monetary policy suggests a central bank’s policy toward the supply of money or the level of some monetary aggregate. • An alternative approach to monetary policy In recent decades, however, central banks have moved away implementation can eliminate the tension from a direct focus on measures of the money supply. The between money and monetary policy primary focus of monetary policy has instead become the value by “divorcing” the quantity of reserves of a short-term interest rate. In the United States, for example, from the interest rate target. the Federal Reserve’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) announces a rate that it wishes to prevail in the federal funds market, where overnight loans are made among • By paying interest on reserve balances at commercial banks. -

Expectations, Open Market Operations, and Changes in the Federal Funds

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ST.LOUIS computation period. This has probably led to better Expectations, Open estimates of reserve requirements by the Trading Desk and the banks, but it has also eliminated the Market Operations, possibility of any contemporaneous response of required reserves to the interest rate. and Changes in the Another significant change made possible by computer technology is the ability of financial Federal Funds Rate institutions to efficiently “sweep” their consumers’ accounts from those with reserve requirements into John B. Taylor those without reserve requirements. These sweeps have allowed required reserve balances to decline he process through which Federal Reserve sharply from about $30 billion in 1990, to $15 bil- decisions about monetary policy are transmit- lion in 1996, to only about $5 to 6 billion today. As Tted to the federal funds market has changed a result, holding Fed balances to facilitate interbank significantly in recent years. In 1994 the Federal payments is of greater importance for many banks Open Market Committee (FOMC) began to issue than holding reserves for legal requirements. At the a public statement whenever it increased or de- same time, technology has improved the speed and creased its target for the federal funds rate. This accuracy with which banks can keep track of their target is now the focus of activities at the Trading payment inflows and outflows and thereby may Desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In have reduced the demand for Fed balances.3 particular, the FOMC directs the Trading Desk to In December 1999 the FOMC further expanded buy and sell securities so that conditions in the and clarified its public announcement policy. -

New Tools for Central Bankers?

A SYMPOSIUM OF VIEWS New Tools For Central Bankers? entral banks worldwide face criticism for the inability of their policies to restore the global economy to historic levels of economic activity. CCentral bank bond buying, it is often charged, has distorted financial markets. Negative real interest rates have weakened many banking sectors. At this summer’s Jackson Hole meeting, Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen proclaimed: “New policy tools, which helped the Federal Reserve respond to the financial crisis and Great Recession, are likely to remain useful in dealing with future downturns. Additional tools may be needed.” What new tools should the central bank community consider? Or has monetary policy been perceived too much as some kind of magical pill? Should fiscal and regulatory reforms come into play? THE MAGAZINE OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC POLICY 220 I Street, N.E., Suite 200 Washington, D.C. 20002 More than forty noted experts share their views. Phone: 202-861-0791 Fax: 202-861-0790 www.international-economy.com [email protected] 6 THE INTERNATIONAL ECONOMY FALL 2016 The answer is not to transition … from the lead role in what essentially has been the equivalent of a “one-person show,” to playing a push central banks supporting role to politicians that finally step up to their economic governance responsibility and lift the con- even deeper into straints to a more comprehensive policy response. Absent such a pivot, the quest for new tools for cen- what has become an tral banks may be associated with a much more disturbing and durable development—that of seeing central banks increasingly “lose- shift from being part of the solution to becoming part of the problem.