The Grammar of Money an Analytical Account of Money As a Discursive Institution in Light of the Practice of Complementary Currencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Mouth Operations: a Swiss Case Study Michael J

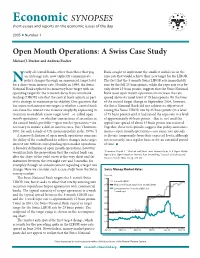

Economic SYNOPSES short essays and reports on the economic issues of the day 2005 I Number 1 Open Mouth Operations: A Swiss Case Study Michael J. Dueker and Andreas Fischer early all central banks, other than those that peg Bank sought to implement the smallest initial rise in the an exchange rate, now explicitly communicate repo rate that would achieve their new target for the LIBOR. Npolicy changes through an announced target level The fact that the 3-month Swiss LIBOR rate immediately for a short-term interest rate. Notably, in 1999, the Swiss rose by the full 25 basis points, while the repo rate rose by National Bank replaced its monetary base target with an only about 15 basis points, suggests that the Swiss National operating target for the 3-month Swiss franc interbank Bank used open mouth operations to increase the rate lending (LIBOR) rate that the central bank adjusts as part spread above its usual level of 15 basis points. By the time of its strategy to maintain price stability. One question that of the second target change in September 2004, however, has arisen with interest rate targets is whether a central bank the Swiss National Bank did not achieve its objective of can cause the interest rate to move simply by expressing its raising the Swiss LIBOR rate by 25 basis points (to a level intention to establish a new target level—so-called open of 75 basis points) until it had raised the repo rate to a level mouth operations—or whether transactions of securities in of approximately 60 basis points—that is, not until the the central bank’s portfolio—open market operations—are typical rate spread of about 15 basis points was restored. -

Iilv'j by Charles Eis Giistein Praise for Occupy Money

6 Creating an Eco„omy W e re Bver,body forewordiilV'J by Charles Eis Giistein Praise for Occupy Money We can create a money system that is the ally, and not the enemy, of all that is precious in the world. We can assign value in a way that is aligned with our emerging con sciousness that the welfare of all depends on the welfare of each: each person, each species, all of life on Earth. We can make money into something we can truly embrace as ours. That, I think, is the heart of the call to occupy money. — Charles Eisenstein, from the Foreword In a world drowning in a tsunami of unrepayable debt, Margrit Kennedy’s timely book provides a geography of hope for practical new money systems that will ensure the rebuilding of new resilient economies of well-being and happiness. In her characteristic plain-language, Mar- grit shows us alternative solutions from around the world to the current usury-debt-money system; these are the seeds that need to be planted in the new economic spring of well-being that is emerging. — Mark Anielski, Economist and author. The Economics of Happiness: Building Genuine Wealth oney OCpilPH Money Creating an Economy Where Everybody Wins MARGRIT KENNEDY with Stephanie Ehrenschwendner Foreword by Charles Eisenstein Translated by Philip Beard PhD new society PUBLISHERS Copyright © 2012 by Margrit Kennedy. All rights reserved. Cover design by Diane McIntosh. Illustrations: © iStock Printed in Canada. First printing September 2012. Paperback isbn: 978-0-86571-731-2 eiSBN: 978-1-55092-524-1 Inquiries regarding requests to reprint all or part of Occupy Money should be addressed to New Society Publishers at the address below. -

The Institutionalist Reaction to Keynesian Economics

Journal of the History of Economic Thought, Volume 30, Number 1, March 2008 THE INSTITUTIONALIST REACTION TO KEYNESIAN ECONOMICS BY MALCOLM RUTHERFORD AND C. TYLER DESROCHES I. INTRODUCTION It is a common argument that one of the factors contributing to the decline of institutionalism as a movement within American economics was the arrival of Keynesian ideas and policies. In the past, this was frequently presented as a matter of Keynesian economics being ‘‘welcomed with open arms by a younger generation of American economists desperate to understand the Great Depression, an event which inherited wisdom was utterly unable to explain, and for which it was equally unable to prescribe a cure’’ (Laidler 1999, p. 211).1 As work by William Barber (1985) and David Laidler (1999) has made clear, there is something very wrong with this story. In the 1920s there was, as Laidler puts it, ‘‘a vigorous, diverse, and dis- tinctly American literature dealing with monetary economics and the business cycle,’’ a literature that had a central concern with the operation of the monetary system, gave great attention to the accelerator relationship, and contained ‘‘widespread faith in the stabilizing powers of counter-cyclical public-works expenditures’’ (Laidler 1999, pp. 211-12). Contributions by institutionalists such as Wesley C. Mitchell, J. M. Clark, and others were an important part of this literature. The experience of the Great Depression led some institutionalists to place a greater emphasis on expenditure policies. As early as 1933, Mordecai Ezekiel was estimating that about twelve million people out of the forty million previously employed in the University of Victoria and Erasmus University. -

Presenting the American Monetary Act (As of July 18, 2010) ©2010 American Monetary Institute, P.O

Presenting the American Monetary Act (as of July 18, 2010) ©2010 American Monetary Institute, P.O. Box 601, Valatie, NY 12184 [email protected] 518-392-5387 “Over time, whoever controls the money system controls the nation.” Stephen Zarlenga, Director Congressman Dennis Kucinich (D-Ohio) made history on December 17th, 2010 when he introduced a version of this Act as the National Employment Emergency Defense Act (NEED Act), HR 6550, which faithfully contains all of these monetary reforms. Introduction Dear Friends, The World economy has been taken down and wrecked by the financial establishment and their economists; and by their supporters in the media they own, and even by some in the executive and legislative branches, in the name of “free markets” and insatiable greed. Shame! Shame on them all! The American Monetary Act (the “Act”) is a comprehensive reform of the present United States money system, and it resolves the current banking crisis. “Reform” is not in its title, because the AMI considers our monetary system to never have been adequately defined in law, but rather to have been put together piecemeal under pressure from particular interests, mainly banking, in pursuit of their own private advantage, without enough regard to our nation’s needs. That is the harsh judgment of history as made clear in The Lost Science of Money, by Stephen Zarlenga (abbreviated LSM).* That book presents the research results of The American Monetary Institute to date and this Act puts the reform process described in Chapter 24 into legislative language. Chapters 1 thru 23 present the historical background and case studies on which Chapter 24 is based. -

Creative Monetary Valorization

PLACE C.. BINDEWALD L.. Validating and Improving the Impact of Complementary Currency Systems: impact assessment frameworks for sustainable development. In: CCS-2013 2nd INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPLEMENATARY CURRENCY SYSTEMS: MULTIPLE MONEYS AND DEVELOPMENT: MAKING PAYMENTS IN DEVERSE ECONOMIES. From 19th to 23rd of June 2013. The Hague. Conference proceedings. The Hague: International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam, 2013. nd 2 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPLEMENTARY CURRENCY SYSTEMS Multiple moneys and development: making payments in diverse economies ISS is The International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam VALIDATING AND IMPROVING THE IMPACT OF COMPLEMENTARY CURRENCY SYSTEMS: impact assessment frameworks for sustainable development PLACE Christophe HEG-Geneva School of Business Administration, Campus Batelle, Bâtiment F, 7, route de Drize, 1227 Carouge, Switzerland. BINDEWALD Leander New Economics Foundation, 3 Jonathan Street, London SE11 5NH, United Kingdom. Corresponding author: [email protected] 19-23 June 2013 International Institute of Social Studies, Kortenaerkade 12, 2518 AX Den Haag, Netherlands. ABSTRACT To bring the credibility and legitimacy required when engaging with public institutions, depending on sustained support from funders and last but not least in order to improve the design and implementation of complementary currency systems (CCS), it is necessary to evidence their impact and validate them as effective and efficient tools to reach sustainable development goals. Recent analysis of their typology, intentional objectives and sporadic impact evaluations didn’t generate enough basic data and understanding to deliver this evidence, especially because of the lack of comprehensive impact analysis research. Only around a fourth of CCS studies even touch upon impact evaluation processes. -

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990S U.S

Explaining the Appearance of Open-Mouth Operations in the 1990s U.S. Christopher Hanes [email protected] Department of Economics SUNY-Binghamton P.O. Box 6000 Binghamton, NY 13902 July 2018 Abstract: In the 1990s it became apparent that changes in the FOMC’s target rate could be implemented through announcements alone - “open mouth operations” - without adjustments to reserve supply or the discount rate. This cannot be explained by standard models of the Fed’s system of policy implementation at the time. It differed from experience in the 1970s, the earlier era of interest-rate targeting, though the structure of implementation appeared essentially similar. I explain the appearance of open-mouth operations as a consequence of longstanding Fed discount-window lending practices, interacting with a decrease after the 1970s in the relative importance of discount borrowing by small banks. Data on discount borrowing by large versus small banks in the 1980s-1990s and the 1970s support my explanation. JEL codes E43, E51, E52, G21. Thanks to James Clouse, Selva Demiralp, Cheryl Edwards, William English, Marvin Goodfried, Kenneth Kuttner and William Whitesell. - 1 - In the 1990s Federal Reserve staff found that market overnight rates changed when the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) signalled it had changed its target fed funds rate, even if the staff made no adjustment to the quantity of reserves supplied through open-market operations. Eventually the volume of bank deposits responded to interest rates through the usual “money demand” channels, and the Fed had to accommodate resulting changes in the quantity of reserves needed to satisfy fractional reserve requirements or clear payments. -

American Monetary Act and the Monetary Transparency Act September 21, 2006; © 2006

Presenting The American Monetary Act and the Monetary Transparency Act September 21, 2006; © 2006. American Monetary Institute, P.O. Box 601, Valatie, NY 12184 Stephen Zarlenga, Director. [email protected] 518-392-5387 Introduction Dear Friends, The American Monetary Act (the “Act”) is a comprehensive reform of the present United States monetary system. “Reform” is not in its title, because the AMI considers our monetary system to never have been adequately defined in law, but rather to have been put together piecemeal under pressure from particular interests, mainly banking, in pursuit of their own private advantage, with little regard to our nation’s needs. That is the harsh judgment of history as made clear in The Lost Science of Money, by Stephen Zarlenga (abbreviated LSM).* That book presents the research results of The American Monetary Institute to date and this Act puts the reform process described in Chapter 24 into legislative language. Chapters 1 thru 23 present the historical background and case studies on which Chapter 24 is based. We recommend serious students of our money system read the book now, and suggest that those who’ve read it, read it again. This Act – a work in progress – has been in preparation since December 2004 and was placed on our web site for public criticism in February 2006, concurrently released in Philadelphia at the Eastern Economic Association Conference, for general comment. It draws substantially from a previous proposal known as “The Chicago Plan,” which was advanced by Professors Henry Simons, Irving Fisher and other leading economists in the 1930s in response to the wreckage of the Great Depression which resulted from our poorly conceived banking system. -

The End of Growth: Adapting to Our New

Advance Praise for The End of Growth Heinberg draws in the big three drivers of inevitable crisis—resource constraints, environmental impacts, and financial system overload—and explains why they are not individual challenges but one integrated system- ic problem. By time you finish this book, you will have come to two conclusions. First, we are not facing a re- cession—this is the end of economic growth. Second, this is not our children’s problem—it is ours. It’s time to get ready, and reading this book is the place to start. — PAUL GILDING, author, The Great Disruption, Former head of Greenpeace International Richard has rung the bell on the limits to growth. This is real. The consequences for economics, finance, and our way of life in the decades ahead will be greater than the consequences of the industrial revolution were for our recent ancestors. Our coming shift from quantity of con- sumption to quality of life is the great challenge of our generation—frightening at times, but ultimately freeing. — JOHN FULLERTON, President and Founder, Capital Institute Why have mainstream economists ignored environ- mental limits for so long? If Heinberg is right, they will 3/567 have a lot of explaining to do. The end of conventional economic growth would be a shattering turn of events—but the book makes a persuasive case that this is indeed what we are seeing. — LESTER BROWN, Founder, Earth Policy Institute and author, World on the Edge Heinberg shows how peak oil, peak water, peak food, etc. lead not only to the end of growth, and also to the beginning of a new era of progress without growth. -

The Nature of Money in Modern Economy –Implications and Consequences

JKAU: Islamic Econ., Vol. 29 No. 2, pp: 57-73 (July 2016) DOI: 10.4197 / Islec. 29-2.4 The Nature of Money in Modern Economy –Implications and Consequences Stephen Zarlenga* and Robert Poteat** *Director, American Monetary Institute (AMI), New York, USA **Senior adviser to the AMI, New York, USA Abstract. This paper discusses the great importance of the monetary question, and briefly examines some of the dominant erroneous concepts of money and their effects upon societies. It also points and links to the great progress currently being made by researchers in this field, so readers can examine them more fully. It presents very brief summaries of what some of the important new papers do. It also aims at helping instructors in outlining a reading curriculum to assist in a long overdue understanding of money power. Finally, the paper presents a money and banking system proposal which has evolved since the Great Depression of the 1930s, and is now ready for implementation and has even been introduced as potential legislation into the United States Congress. 1. Introduction Perhaps no subject as important to mankind as the Finally, the authors will describe a money and nature of money has been so neglected and banking system proposal they are very familiar misunderstood in both the popular and professional with, which has evolved since the Great Depression mind, to the great detriment of the intelligent and of the 1930s, and is now ready for implementation just operation of societies. The author’s intent is to and has even been introduced as potential legislation discuss the great importance of the monetary into the United States Congress. -

Breaking the Mould: an Institutionalist Political Economy Alternative to the Neoliberal Theory of the Market and the State Ha-Joon Chang, May 2001

Breaking the Mould An Institutionalist Political Economy Alternative to the Neoliberal Theory of the Market and the State Ha-Joon Chang Social Policy and Development United Nations Programme Paper Number 6 Research Institute May 2001 for Social Development The United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) thanks the governments of Denmark, Finland, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom for their core funding. Copyright © UNRISD. Short extracts from this publication may be reproduced unaltered without authorization on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to UNRISD, Palais des Nations, 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. UNRISD welcomes such applications. The designations employed in UNRISD publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNRISD con- cerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for opinions expressed rests solely with the author(s), and publication does not constitute endorse- ment by UNRISD. ISSN 1020-8208 Contents Acronyms ii Acknowledgements ii Summary/Résumé/Resumen iii Summary iii Résumé iv Resumen v 1. Introduction 1 2. The Evolution of the Debate: From “Golden Age Economics” to Neoliberalism 1 3. The Limits of Neoliberal Analysis of the Role of the State 3 3.1 Defining the free market (and state intervention) 4 3.2 Defining market failure 6 3.3 The market primacy assumption 8 3.4 Market, state and politics 11 4. -

Schedule for May 9-11 Conference (PDF)

WELCOME Welcome to the 39th Eastern Economic Association Annual Meetings in New York, N.Y. Our incoming President-Elect Solomon Polachek, session chairs, organizers, and review committee have done a great job putting together this year’s program, which I hope you will find as intellectually exciting as I do. The program furthers the EEA’s tradition of encouraging intellectual debate, open to all points of view. I'd particularly like to welcome those attending the conference from other regions of the country and other parts of the world. This has been a year marked by challenges in the New York area, with hurricane Sandy closing down the Association’s home office for two weeks and postponing the New York District Fed Challenge program. As many of you know, the EEA has partnered with the Federal Reserve Banks of New York and Philadelphia, and the Federal Reserve Board of Governors to sponsor the Federal Reserve Bank Challenge. This program is a competition by which five person teams from various colleges make 15-minute presentations to academics, practitioners, and Fed economists as to whether the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee should raise, maintain, or lower the targeted Fed Funds Rate. Subsequently the panel of expert judges questions the students on a wide range of issues. By working with the Federal Reserve System, the EEA is fulfilling one of its missions by promoting economic education. I would like to thank the members of the Fed Challenge Advisory Board for their service: Howard Freeman, Ray Stone, CEO Stone & McCarthy Research Associates, Hank Bitten, Former Supervisor of Social Studies and Economics at Indian Hills High School and now happily retired, Blake Gwinn, Federal Reserve Bank of New York Markets Group, Charles Steindel, Chief Economist for the State of New Jersey, student representative Victor Castaneda, and professors Julio Huato (St. -

Complementary Currencies: an Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles

sustainability Article Complementary Currencies: An Analysis of the Creation Process Based on Sustainable Local Development Principles Francisco Javier García-Corral 1,* , Jaime de Pablo-Valenciano 2 , Juan Milán-García 2 and José Antonio Cordero-García 3 1 Research Group: Almeria Group of Applied Economy (SEJ-147), University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain 2 Department of Business and Economics, Applied Economic Area, University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] (J.d.P.-V.); [email protected] (J.M.-G.) 3 Department of Law, Financial and Tax Law, University of Almeria, 04120 Almeria, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 July 2020; Accepted: 13 July 2020; Published: 15 July 2020 Abstract: Complementary currencies are a reality and are being applied both globally and locally. The aim of this article is to explain the viability of this type of currency and its application in local development, in this case, in a rural mountain municipality in the province of Almería (Spain) called Almócita. The Plus, Minus, Interesting (PMI); “Flying Balloon”; and Strength, Weakness, Opportunity (SWOT) analysis methodologies will be used to carry out the study. Finally, a ranking of success factors will be carried out with a brainstorming exercise. As to the results, there are, a priori, more advantages than disadvantages of implementing these currencies, but the local population has clarified that their main concern is depopulation along with a lack of varied work. As a counterpart to this and strengths or advantages, almost all the participants mention the support from the Almócita city council and the initiatives that are constantly being promoted.