The Women's Philharmonic: Its History and Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The-Piano-Teaching-Legacy-Of-Solomon-Mikowsky.Pdf

! " #$ % $%& $ '()*) & + & ! ! ' ,'* - .& " ' + ! / 0 # 1 2 3 0 ! 1 2 45 3 678 9 , :$, /; !! < <4 $ ! !! 6=>= < # * - / $ ? ?; ! " # $ !% ! & $ ' ' ($ ' # % %) %* % ' $ ' + " % & ' !# $, ( $ - . ! "- ( % . % % % % $ $ $ - - - - // $$$ 0 1"1"#23." 4& )*5/ +) * !6 !& 7!8%779:9& % ) - 2 ; ! * & < "-$=/-%# & # % %:>9? /- @:>9A4& )*5/ +) "3 " & :>9A 1 The Piano Teaching Legacy of Solomon Mikowsky by Kookhee Hong New York City, NY 2013 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by Koohe Hong .......................................................3 Endorsements .......................................................................3 Comments ............................................................................5 Part I: Biography ................................................................12 Part II: Pedagogy................................................................71 Part III: Appendices .........................................................148 1. Student Tributes ....................................................149 2. Student Statements ................................................176 -

Musicweb International December 2020 NAXOS RELEASES: LATE

NAXOS RELEASES: LATE 2020 By Brian Wilson It may be that I’ve been particularly somnolent recently, but a particularly fruitful series of Naxos releases in late 2020 has made me take notice of what I’ve been missing earlier this year, so I’ve included some of them, too. Index [page numbers in brackets] ALYABIEV Piano Trios (+ GLINKA, RUBINSTEIN: Russian Piano Trios 1) [5] Corelli’s Band: Violin Sonatas by Corelli and followers [2] FREDERICK II (Frederick The Great): Flute Sonatas [4] GERSHWIN Concerto in F (+ PISTON Symphony No.5, etc.) [11] GLINKA Trio pathétique (see ALYABIEV) [5] GOMPPER Cello Concerto, Double Bass Concerto, Moonburst [15] Michael HAYDN Missa Sancti Nicolai Tolentini; Vesperæ [5] HUMPERDINCK Music for the Stage [7] KORNGOLD Suite, Op.23; Piano Quintet [10] Laudario di Cortona excerpts (see PÄRT) [13] NOVÁK V Tatrách (In the Tatra Mountains); Lady Godiva; O věčné touze (Eternal Longing) [8] - Jihočeská suita (‘South Bohemian Suite’); Toman a lesní panna (‘Toman and the Wood Nymph’) [9] PÄRT And I heard a voice…, etc. ( … and … with SHAW, WOLFE, Laudario di Cortona) [13] PISTON Symphony No.5 (see GERSHWIN) [11] RUBINSTEIN Piano Trio (see ALYABIEV) [5] RUTTER Anthems, Hymns and Gloria for Brass Band [12] SCHMITT La Tragédie de Salomé, etc. [8] SCHUMANN Robert and Clara Music for violin and piano [6] VILLA-LOBOS Complete Symphonies [9] WALTON Piano Quintet and other Chamber Works with Violin and Piano [11] WEINBERG Clarinet Concerto; Clarinet Sonata; Chamber Symphony No.4 [12] WIDOR Organ Symphonies 4 (Nos. 8 and 10) [7] * The Art of Classical Guitar Transcription Christophe Dejour [15] Carmina predulcia (C15 Songbook) [1] Christmas Concertos [2] Heaven Full of Stars (contemporary choral) [13] Stille Nacht: Christmas Carols for Guitar [14] *** Carmina predulcia (‘very sweet songs’) is a recording of music from the fifteenth-century Schedelschen Liederbuch (Schedel Songbook). -

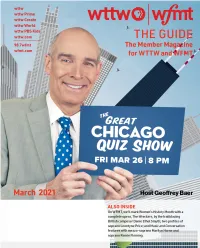

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

July-August, 2016 from the Editor Welcome to the July-August 2016 Edition of the AAA Newsletter

NewsletterAMERICAN ACCORDIONISTS’ ASSOCIATION A bi-monthly publication of the American Accordionists’ Association July-August, 2016 From the Editor Welcome to the July-August 2016 edition of the AAA Newsletter. Congratulations to all those that made the 2016 Festival in Buffalo a tremen- dous success. The annual festival showcased a diverse and talented array of ac- cordionists, performing a variety of genres of music. You will have all received information that this Newsletter is now available in both a printed format and also as a .pdf file. While some prefer to have a printed copy to browse at leisure, there are also a number of people who enjoy having their news presented in an electronic format, and thus a digital version is another means for the AAA to take advantage of the technology available today. Be sure to let the AAA know of your preference, and they will be happy to arrange your Newsletter delivery accordingly. Once again my sincere thanks to all those that have assisted in providing news items and pictures, including your very own AAA Board of Director Rita Barnea who is always an avid supporter of the AAA Newsletter sharing a variety of news items from around the country. Items for the September 2016 Newsletter can be sent to me at [email protected] or to the official AAA e-mail address at: [email protected]. Please include ‘AAA Newsletter’ in the subject box, so that we don’t miss any items that come in. Text should be sent within the e-mail or as a Word attachment. -

Program Book Final 1-16-15.Pdf

4 5 7 BUFFALO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TABLE OF CONTENTS | JANUARY 24 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 BPO Board of Trustees/BPO Foundation Board of Directors 11 BPO Musician Roster 15 Happy Birthday Mozart! 17 M&T Bank Classics Series January 24 & 25 Alan Parsons Live Project 25 BPO Rocks January 30 Ben Vereen 27 BPO Pops January 31 Russian Diversion 29 M&T Bank Classics Series February 7 & 8 Steve Lippia and Sinatra 35 BPO Pops February 13 & 14 A Very Beary Valentine 39 BPO Kids February 15 Corporate Sponsorships 41 Spotlight on Sponsor 42 Meet a Musician 44 Annual Fund 47 Patron Information 57 CONTACT VoIP phone service powered by BPO Administrative Offices (716) 885-0331 Development Office (716) 885-0331 Ext. 420 BPO Administrative Fax Line (716) 885-9372 Subscription Sales Office (716) 885-9371 Box Office (716) 885-5000 Group Sales Office (716) 885-5001 Box Office Fax Line (716) 885-5064 Kleinhans Music Hall (716) 883-3560 Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra | 499 Franklin Street, Buffalo, NY 14202 www.bpo.org | [email protected] Kleinhan's Music Hall | 3 Symphony Circle, Buffalo, NY 14201 www.kleinhansbuffalo.org 9 MESSAGE FROM BOARD CHAIR Dear Patrons, Last month witnessed an especially proud moment for the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra: the release of its “Built For Buffalo” CD. For several years, we’ve presented pieces commissioned by the best modern composers for our talented musicians, continuing the BPO’s tradition of contributing to classical music’s future. In 1946, the BPO made the premiere recording of the Shostakovich Leningrad Symphony. Music director Lukas Foss was also a renowned composer who regularly programmed world premieres of the works of himself and his contemporaries. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

Singing in English in the 21St Century: a Study Comparing

SINGING IN ENGLISH IN THE 21ST CENTURY: A STUDY COMPARING AND APPLYING THE TENETS OF MADELEINE MARSHALL AND KATHRYN LABOUFF Helen Dewey Reikofski Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2015 APPROVED:….……………….. Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor Stephen Dubberly, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Committee Member Stephen Austin, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Vocal Studies … James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Reikofski, Helen Dewey. Singing in English in the 21st Century: A Study Comparing and Applying the Tenets of Madeleine Marshall and Kathryn LaBouff. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2015, 171 pp., 6 tables, 21 figures, bibliography, 141 titles. The English diction texts by Madeleine Marshall and Kathryn LaBouff are two of the most acclaimed manuals on singing in this language. Differences in style between the two have separated proponents to be primarily devoted to one or the other. An in- depth study, comparing the precepts of both authors, and applying their principles, has resulted in an understanding of their common ground, as well as the need for the more comprehensive information, included by LaBouff, on singing in the dialect of American Standard, and changes in current Received Pronunciation, for British works, and Mid- Atlantic dialect, for English language works not specifically North American or British. Chapter 1 introduces Marshall and The Singer’s Manual of English Diction, and LaBouff and Singing and Communicating in English. An overview of selected works from Opera America’s resources exemplifies the need for three dialects in standardized English training. -

6. the Evolving Role of Music Journalism Zachary Woolfe and Alex Ross

Classical Music Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges Classical Music This kaleidoscopic collection reflects on the multifaceted world of classical music as it advances through the twenty-first century. With insights drawn from Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges leading composers, performers, academics, journalists, and arts administrators, special focus is placed on classical music’s defining traditions, challenges and contemporary scope. Innovative in structure and approach, the volume comprises two parts. The first provides detailed analyses of issues central to classical music in the present day, including diversity, governance, the identity and perception of classical music, and the challenges facing the achievement of financial stability in non-profit arts organizations. The second part offers case studies, from Miami to Seoul, of the innovative ways in which some arts organizations have responded to the challenges analyzed in the first part. Introductory material, as well as several of the essays, provide some preliminary thoughts about the impact of the crisis year 2020 on the world of classical music. Classical Music Classical Classical Music: Contemporary Perspectives and Challenges will be a valuable and engaging resource for all readers interested in the development of the arts and classical music, especially academics, arts administrators and organizers, and classical music practitioners and audiences. Edited by Paul Boghossian Michael Beckerman Julius Silver Professor of Philosophy Carroll and Milton Petrie Professor and Chair; Director, Global Institute for of Music and Chair; Collegiate Advanced Study, New York University Professor, New York University This is the author-approved edition of this Open Access title. As with all Open Book publications, this entire book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. -

Queer Abstraction

UNDER CONSTRUCTION PERFORMING CRITICAL IDENTITY EDITED BY MARIE-ANNE KOHL Under Construction State of the Arts–Reflecting Contemporary Cultural Expression Volumes in the series: Under Construction: Performing Critical Identity ISBN 978-3-03897-499-4 (Hbk); ISBN 978-3-03897-500-7 (PDF) Self-Representation in an Expanded Field: From Self-Portraiture to Selfie, Contemporary Art in the Social Media Age ISBN 978-3-03897-564-9 (Hbk); ISBN 978-3-03897-565-6 (PDF) Marie-Anne Kohl (Ed.) Under Construction Performing Critical Identity MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tianjin •Tokyo • Cluj EDITOR Marie-Anne Kohl Research Institute for Music Theater Studies, University of Bayreuth, Thurnau, Germany EDITORIAL OFFICE MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated below: Author 1, and Author 2. 2021. Chapter Title. In Under Construction: Performing Critical Identity. Edited by Marie-Anne Kohl. Basel: MDPI, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03897-499-4 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03897-500-7 (PDF) ISSN: 2624-9839 (Print); ISSN: 2624-9847 (Online) doi.org/10.3390/books978-3-03897-500-7 Cover image adapted from work by Mamba Azul–stock.adobe.com. © 2021 by the authors. Chapters in this volume are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book taken as a whole is © 2021 MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

The Changing Reputation and Legacy of John Powell (1882-1963)

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 “The Nonmusical Message Will Endure With It:” The Changing Reputation and Legacy of John Powell (1882-1963) Karen Adam Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2692 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Karen Adam 2012 All Rights Reserved “The Nonmusical Message Will Endure With It:” The Changing Reputation and Legacy of John Powell (1882-1963) A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Karen Elizabeth Adam Bachelor of Arts, University of Richmond, 2006 Director: Dr. John T. Kneebone Associate Professor, Virginia Commonwealth University Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2012 Thanks I may have completed this project over several months, but it is the result of a lifetime of accumulated knowledge and experiences. Citations throughout the thesis acknowledge my debt to the scholars and works that came before me. The rest of this page contains my most sincere and heartfelt gratitude toward all others, most particularly to: My Lord and Savior, whose love and grace are sufficient and boundless, and through whom all things are possible. My parents, for listening to everything with patience, insight, and love, and for doing much to encourage me to persevere. -

View Commencement Program

THOSE WHO EXCEL REACH THE STARS FRIDAY, MAY 10, 2019 THE RIVERSIDE CHURCH MANHATTAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC NINETY-THIRD COMMENCEMENT Processional The audience is requested to rise and remain standing during the processional. ANTHONY DILORENZO “The Golden Palace and the Steamship” from The Toymaker (b. 1967) WILLIAM WALTON Crown Imperial: Coronation March (1902–1983) (arr. J. Kreines) BRIAN BALMAGES Fanfare canzonique (b. 1975) Commencement Brass and Percussion Ensemble Kyle Ritenauer (BM ’11, MM ’15), Conductor Gustavo Leite (MM ’19), trumpet Changhyun Cha (MM ’20), trumpet Caleb Laidlaw (BM ’18, MM ’20), trumpet Sean Alexander (BM ’20), trumpet Imani Duhe (BM ’20), trumpet Matthew Beesmer (BM ’20), trumpet Olivia Pidi (MM ’19), trumpet Benjamin Lieberman (BM ’22), trumpet Kevin Newton (MM ’20), horn Jisun Oh (MM ’19), horn Eli Pandolfi (BM ’20), horn Liana Hoffman (BM ’20), horn Emma Potter (BM ’22), horn Kevin Casey (MM ’20), trombone Kenton Campbell (MM ’20), trombone Julia Dombroski (MM ’20), trombone David Farrell (MM ’20), trombone Morgan Fite (PS ’19), bass trombone Patrick Crider (MM ’19), bass trombone Mark Broschinsky (DMA ’11), euphonium Logan Reid (BM ’20), bass trombone Emerick Falta (BM ’21), tuba Brandon Figueroa (BM ’20), tuba Cooper Martell (BM ’20), percussion Hyunjung Choi (BM ’19), percussion Tae McLoughlin (BM ’20), percussion Hamza Able (BM ’20), percussion Introduction Monica Coen Christensen, Dean of Students Greetings Lorraine Gallard, Chair of the Board of Trustees James Gandre, President Presentation of Commencement Awards Laura Sametz, Member of the Musical Theatre faculty and the Board of Trustees Musical Interlude GEORGE LEWIS Artificial Life 2007 (b. 1952) Paul Mizzi (MM ’19), flute Wickliffe Simmons (MM ’19), cello Edward Forstman (MM ’19), piano Thomas Feng (MM ’19), piano Jon Clancy (MM ’19), percussion Presentation of the President’s Medal for Distinguished Service President Gandre Joyce Griggs, Executive Vice President and Provost John K. -

Counting the Music Industry: the Gender Gap

October 2019 Counting the Music Industry: The Gender Gap A study of gender inequality in the UK Music Industry A report by Vick Bain Design: Andrew Laming Pictures: Paul Williams, Alamy and Shutterstock Hu An Contents Biography: Vick Bain Contents Executive Summary 2 Background Inequalities 4 Finding the Data 8 Key findings A Henley Business School MBA graduate, Vick Bain has exten sive experience as a CEO in the Phase 1 Publishers & Writers 10 music industry; leading the British Academy of Songwrit ers, Composers & Authors Phase 2 Labels & Artists 12 (BASCA), the professional as sociation for the UK's music creators, and the home of the Phase 3 Education & Talent Pipeline 15 prestigious Ivor Novello Awards, for six years. Phase 4 Industry Workforce 22 Having worked in the cre ative industries for over two decades, Vick has sat on the Phase 5 The Barriers 24 UK Music board, the UK Music Research Group, the UK Music Rights Committee, the UK Conclusion & Recommendations 36 Music Diversity Taskforce, the JAMES (Joint Audio Media in Education) council, the British Appendix 40 Copyright Council, the PRS Creator Voice program and as a trustee of the BASCA Trust. References 43 Vick now works as a free lance music industry consult ant, is a director of the board of PiPA http://www.pipacam paign.com/ and an exciting music tech startup called Delic https://www.delic.net work/ and has also started a PhD on gender diversity in the UK music industry at Queen Mary University of London. Vick was enrolled into the Music Week Women in Music Awards ‘Roll Of Honour’ and BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour Music Industry Powerlist.