Parliamentary Enclosure and Changes in Landownership in an Upland Environment: Westmorland, C.1770–1860

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

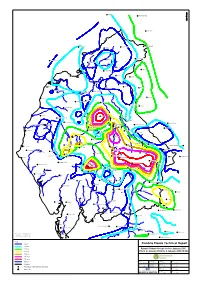

Cumbria Floods Technical Report

Braidlie Kielder Ridge End Kielder Dam Coalburn Whitehill Solwaybank Crewe Fell F.H. Catlowdy Wiley Sike Gland Shankbridge Kinmount House C.A.D.Longtown Walton Haltwhistle Fordsyke Farm Drumburgh Brampton Tindale Carlisle Castle Carrock Silloth Geltsdale Cumwhinton Knarsdale Abbeytown Kingside Blackhall Wood Thursby WWTW Alston STW Mawbray Calder Hall Westward Park Farm Broadfield House Haresceugh Castle Hartside Quarry Hill Farm Dearham Caldbeck Hall Skelton Nunwick Hall Sunderland WWTW Penrith Langwathby Bassenthwaite Mosedale Greenhills Farm Penrith Cemetery Riggside Blencarn Cockermouth SWKS Cockermouth Newton Rigg Penrith Mungrisdale Low Beckside Cow Green Mungrisdale Workington Oasis Penrith Green Close Farm Kirkby Thore Keswick Askham Hall Cornhow High Row Appleby Appleby Mill Hill St John's Beck Sleagill Brackenber High Snab Farm Balderhead Embankment Whitehaven Moorahall Farm Dale Head North Stainmore Summergrove Burnbanks Tel Starling Gill Brough Ennerdale TWks Scale Beck Brothers Water Honister Black Sail Ennerdale Swindale Head Farm Seathwaite Farm Barras Old Spital Farm St Bees Wet Sleddale Crosby Garrett Wastwater Hotel Orton Shallowford Prior Scales Farm Grasmere Tannercroft Kirkby Stephen Rydal Hall Kentmere Hallow Bank Peagill Elterwater Longsleddale Tebay Brathay Hall Seascale White Heath Boot Seathwaite Coniston Windermere Black Moss Watchgate Ravenstonedale Aisgill Ferry House Ulpha Duddon Grizedale Fisher Tarn Reservoir Kendal Moorland Cottage Sedburgh Tower Wood S.Wks Sedbusk Oxen Park Tow Hill Levens Bridge End Lanthwaite Grizebeck High Newton Reservoir Meathop Far Gearstones Beckermonds Beetham Hall Arnside Ulverston P.F. Leck Hall Grange Palace Nook Carnforth Crag Bank Pedder Potts No 2 Barrow in Furness Wennington Clint Bentham Summerhill Stainforth Malham Tarn This map is reproduced from the OS map by the Environment Agency with Clapham Turnerford the permission of the controller of Her Majesty's Stationary Office, Crown Copyright. -

Norman Rule Cumbria 1 0

NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY N O R M A N R U L E I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 NORMAN RULE I N C U M B R I A 1 0 9 2 – 1 1 3 6 B y RICHARD SHARPE Pr o f essor of Diplomat i c , U n i v e r sity of Oxfo r d President of the Surtees Society A lecture delivered to Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society on 9th April 2005 at Carlisle CUMBERLAND AND WESTMORLAND ANTIQUARIAN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Tract Series Vol. XXI C&W TRACT SERIES No. XXI ISBN 1 873124 43 0 Published 2006 Acknowledgements I am grateful to the Council of the Society for inviting me, as president of the Surtees Society, to address the Annual General Meeting in Carlisle on 9 April 2005. Several of those who heard the paper on that occasion have also read the full text and allowed me to benefit from their comments; my thanks to Keith Stringer, John Todd, and Angus Winchester. I am particularly indebted to Hugh Doherty for much discussion during the preparation of this paper and for several references that I should otherwise have missed. In particular he should be credited with rediscovering the writ-charter of Henry I cited in n. -

Lyvennet - Our Journey

Lyvennet - Our Journey David Graham 24th September 2014 Agenda • Location • Background • Housing • Community Pub • Learning • CLT Network Lyvennet - Location The Lyvennet Valley • Villages - Crosby Ravensworth, Maulds Meaburn, Reagill and Sleagill • Population 750 • Shop – 4mls • Bank – 7 mls • A&E – 30mls • Services – • Church, • Primary School, • p/t Post Office • 1 bus / week • Pub The Start – late 2008 • Community Plan • Housing Needs Survey • Community Feedback Cumbria Rural Housing Trust Community Land Trust (CLT) The problem • 5 new houses in last 15 years • Service Centre but losing services • Stagnating • Affordability Ratio 9.8 (House price / income) Lyvennet Valley 5 Yearly Average House Price £325 Cumbria £300 £275 0 £250 0 Average 0 , £ £225 £182k £200 £175 £150 2000- 2001- 2002- 2003- 2004- 2005- 2006- 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Years LCT “Everything under one roof” Local Residents Volunteers Common interest Various backgrounds Community ‘activists’ Why – Community Land Trust • Local occupancy a first priority • No right to buy • Remain in perpetuity for the benefit of the community • All properties covered by a Local Occupancy agreement. • Reduced density of housing • Community control The community view was that direct local stewardship via a CLT with expert support from a housing association is the right option, removing all doubt that the scheme will work for local people. Our Journey End March2011 Tenders Lyvennet 25th Jan -28th Feb £660kHCAFunding Community 2011 £1mCharityBank Developments FullPlanning 25th -

Kendal Town Council Report

Page 1 of 162 KENDAL TOWN COUNCIL Notice of Meeting PLANNING COMMITTEE Monday, 6th June 2016 at 6.30 p.m. in the Georgian Room, the Town Hall, Kendal Committee Membership (7 Members) Jon Robinson (Chair) Austen Robinson (Vice-Chair) Alvin Finch Keith Hurst-Jones Lynne Oldham Matt Severn Kath Teasdale AGENDA 1. APOLOGIES 2. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION Any member of the public who wishes to ask a question, make representations or present a deputation or petition at this meeting should apply to do so before the commencement of the meeting. Information on how to make the application is available on the Council’s Website - www/kendaltowncouncil.gov.uk/Statutory Information/General/ Guidance on Public Participation at Kendal Town Council Meetings or by contacting the Town Clerk on 01539 793490. 3. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To receive declarations by Members and/or co-optees of interests in respect of items on this Agenda [In accordance with the revised Code of Conduct, Members are required to declare any Disclosable Pecuniary Interests (DPIs) or Other Registrable interests (ORIs) which have not already been declared in the Council’s Register of Interests. Members are reminded that it is a criminal offence not to declare a DPI, either in the Register or at the meeting. In the interests of clarity and transparency, Members may wish to declare any DPI which they have already declared in the Register, as well as any ORI.] 4. MINUTES OF MEETING HELD ON 23RD MAY 2016 (see attached) 5. MATTERS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MINUTES, NOT ON AGENDA 6. CUMBRIA MINERALS AND WASTE LOCAL PLAN CONSULTATION (see attached x6) 7. -

Land at Ormside Hall

Lot 1 LAND AT ORMSIDE HALL great ormside, appleby, cumbria ca16 6ej Lot 2 (edged blue on the sale plan) Solicitors 61.89 ACRES (25.08 HECTARES) 50.12 acres (20.28 hectares) of productive grassland and rough Kilvington Solicitors, Westmorland House, Kirkby Stephen CA17 4QT OR THEREABOUTS OF grazing, part with river frontage. The boundaries are a mixture of post t: 017683 71495 and wire fencing and hedges. e: [email protected] PRODUCTIVE GRASSLAND Description Tenure SITUATED ON THE EDGE OF The land is all classified as Grade 3 under the Natural England The land is subject to a farm business tenancy (FBT) agreement Agricultural Land Classification Map for the North West region. The soil regulated by the Agricultural Tenancies Act 1995 that is due to GREAT ORMSIDE. type of Lot 1 is base-rich loamy and clayey soils and the majority of Lot terminate on 31st March 2019. The FBT agreement contains other land 2 being described as loamy and clayey floodplain soils with moderate not included within the sale and on completion of a sale the full rent will land at ormside hall, great ormside, fertility. be retained by the vendor for the remainder of the term. appleby, cumbria ca16 6ej General Information The land is sold freehold, subject to tenancy, with vacant possession delivered upon 1st April 2019. For sale as a whole or in two lots by private treaty. Services Both lots have access to mains water supplies via field troughs. Both Method of sale Lot 1 and Lot 2 require sub-meters to be installed which will be the responsibility of the vendors. -

Helsington Parish Council Community Led Plan

Helsington Parish Council Community Led Plan December 2016 The material contained in this plot has been obtained from an Ordnance Survey map with kind permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office License No. LA100024277 CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 5 Things you like most about the Parish 5 Things you like least about the Parish 5 What you would most like to see for the future of the Parish 6 2. An Introduction 7 Location 7 Population 7 Villages, hamlets and surroundings 7 Transport 8 Economy 8 3. Background to the Plan 9 4. The Process 10 5. Summary of the Results 12 Initial Survey 12 Things you like most about the Parish 12 Things you like least about the Parish 12 What you would most like to see for the future of the Parish 12 Detailed Questionnaire 13 Profile of Respondents 13 6. Actions 15 Theme 1 - Housing 15 1.1 Support for affordable housing 15 1.2 Concern about use of greenfield sites 15 1.3 Consideration of sheltered housing 15 1.4 Restriction on holiday or second homes 16 Theme 2 - Road Safety 16 2.1 Speed of traffic 16 2.2 Safety of road users and property 16 Theme 3 - Sustainable Environment 17 3.1 Protecting and enhancing the wider countryside 17 3.2 Flooding and drainage 17 3.3 Renewable energy 18 3.4 Access to the countryside 18 3.5 Dog fouling 18 Theme 4 - Vibrant Communities 19 4.1 Providing jobs for local people 19 4.2 Developing infrastructure 19 4.3 Planning for safety 19 4.4 Improving social cohesion 20 7. -

Great Ormside

The News Magazine of the ‘Heart of Eden’ Team Ministry St. Lawrence, Appleby; St. John, Murton-cum-Hilton; St. James, Ormside; St. Peter, Great Asby; St. Margaret & St. James, Long Marton; St. Cuthbert, Dufton; St. Cuthbert, Milburn with additional information from Methodist Churches at The Sands, Appleby, Great Asby & Dufton with Knock Methodist Church The Church of Our Lady of Appleby The Local Communities and Organisations of Appleby and the Mid-Eden Valley St. Lawrence Church, Appleby What’s On in The Heart of Eden in October? Food Bank Collection, every Tuesday, Sands Methodist, 10:30; Friday , St. Lawrence’s Church, 11.00 – 12.00 Date Time Place What?? 1st 1~ 3:30pm Appleby Health Centre Hearing Loss drop in 1st 7:30pm RBL Clubhouse RBL branch meeting 1st 2pm Guide Hut Inner Wheel Whist & Dominoes 1st 7:30pm Long Marton Village Hall Pottery Group 1st 7:30pm Maulds Meaburn V.I. Dr. Carl Hallam talks about MSF 1st 7:30 – 9:30pm Milburn Village Hall (and every Thursday) Milburn Art Club 2nd 7:30pm Brampton Memorial Hall Long Marton Church: Autumn Supper 2nd 7:30pm Brampton Village Hall Autumn Supper 3rd 10am Appleby Cloisters Curryaid Cake and Christmas Card Stall 3rd 10am – noon Appleby Medical Practice Flu Clinic and Coffee morning 3rd 9:30 – 11:30am Appleby Market Hall Supper Room Coffee Morning in aid of Ladies’ Friendship 3rd 8pm Dufton Village Hall World Cup Rugby: England v. Australia 4th 10:30am Appleby Parish Church APC Harvest Festival 4th 6:30pm St. Cuthbert’s Milburn Harvest Songs of Praise 4th 3pm St. -

Affordable Homes for Local People: the Effects and Prospects

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Liverpool Repository Affordable homes for local communities: The effects and prospects of community land trusts in England Dr Tom Moore August 2014 Acknowledgements This research study was funded by the British Academy Small Grants scheme (award number: SG121627). It was conducted during the author’s employment at the Centre for Housing Research at the University of St Andrews. He is now based at the University of Sheffield. Thanks are due to all those who participated in the research, particularly David Graham of Lyvennet Community Trust, Rosemary Heath-Coleman of Queen Camel Community Land Trust, Maria Brewster of Liverpool Biennial, and Jayne Lawless and Britt Jurgensen of Homebaked Community Land Trust. The research could not have been accomplished without the help and assistance of these individuals. I am also grateful to Kim McKee of the University of St Andrews and participants of the ESRC Seminar Series event The Big Society, Localism and the Future of Social Housing (held in St Andrews on 13-14th March 2014) for comments on previous drafts and presentations of this work. All views expressed in this report are solely those of the author. For further information about the project and future publications that emerge from it, please contact: Dr Tom Moore Interdisciplinary Centre of the Social Sciences University of Sheffield 219 Portobello Sheffield S1 4DP Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0114 222 8386 Twitter: @Tom_Moore85 Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................. i 1. Introduction to CLTs ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 The policy context: localism and community-led housing ........................................................... -

The Vale of Lyvennet

The Vale Of Lyvennet By John Salkeld Bland The Vale Of Lyvennet INTRODUCTION. The river Lyvennet rises on the northern side of the range of hills stretching eastwards across Westmorland from Shap Fells. It runs through the parishes of Crosby Ravensworth and Morland, receives the tributary stream of the Leith, and falls into the Eden near Temple Sowerby. The distance from its source to its outfall is less than ten miles measured in a straight line; but the little valley is full of varied interest, to which each age has contributed a share. Half way down the stream, and out on the west, lies Reagill, and in it, Wyebourne; and Wyebourne was the home of John Salkeld Bland, who, nearly fifty years ago, compiled this manuscript history of "The Vale of Lyvennet." John Bland's grandfather was a yeoman farming his own land at Reagill. He had a family of two sons, Thomas and William, between whom he divided it; Thomas, who was an artist and sculptor of no mean ability, remaining at Reagill, while William established himself at Wyebourne, a mile away, married, and also had two children; one being John Bland himself, the other a daughter, now Mrs. Dufton, to whom the thanks of this Society are due for use of her brother's manuscript, and for her kindness in supplying information about the family. John Bland was only six months old when he lost his mother, from whom, perhaps, he inherited a constitutional delicacy from which he always suffered. He was educated at the well-known school at Reagill, and afterwards at Croft House, Brampton. -

Community Flood Management Toolkit V1.0 Community Flood Group “Toolkit” 10 Components of Community Flood Management

Patterdale Parish Community Flood Group Community Flood Management Toolkit V1.0 Community Flood Group “Toolkit” 10 Components of Community Flood Management 1. Water 3. River & Beck Storage Areas 2. Tree Planting Modification 5. Gravel Traps 4. Leaky Dams & Woody Debris 6. Watercourse, Gulley, 7. Gravel Management Drain & Culvert Maintenance 8. Community Flood Defences 9. Community Emergency 10. Household Flood Defences & Planning Emergency Planning 2 Example “Toolkit” Opportunities in Glenridding 1. Water Storage 2. Tree Planting for 3. River & Beck 4. Leaky Dams & Woody 5. Gravel Traps Areas stabilisation Modification between Debris Below Bell Cottage, By Keppel Cove Above Greenside, Catstycam, Gillside & Greenside – From Greenside to Helvellyn Grassings Other Upstream Options Brown Cove stabilise banks, slow the flow on tributary becks 6. Watercourse, Gulley, 7. Gravel Management Above & Below Glenridding Drain & Culvert 10. Household Flood Defences Bridge, as Beck Mouth 9. Community Emergency Maintenance Planning & Emergency Planning Flood Gates, Pumps, Emergency Drains & Culverts in the village Emergency Wardens 8. Community Flood Defences Stores Flood Stores Village Hall Road Beck Wall Sandbags 1. Water Storage Areas The What & Why Enhanced water storage areas to capture & hold water for as long as possible to slow the flow downstream. Can utilise existing meadows or be more industrial upstream dams eg Hayeswater, Keppel Cove. Potential Opportunities Partners Required Glenridding • Landowners • Ullswater • Natural England • Keppel Cove • EA • Grassings • UU Grisedale • LDNP • Grisedale Valley • NT Patterdale • Above Rookings on Place Fell Keys to Success/Issues Hartsop • TBC • Landowner buy-in • Landowner compensation (CSC) • Finance Barriers to Success • Lack of the above • Cost 2. Tree Planting The What & Why Main benefits around 1) soil stabilisation, 2) increased evaporation (from leaf cover), 3) sponge effect and 4) hydraulic roughness. -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Landform Studies in Mosedale, Northeastern Lake District: Opportunities for Field Investigations

Field Studies, 10, (2002) 177 - 206 LANDFORM STUDIES IN MOSEDALE, NORTHEASTERN LAKE DISTRICT: OPPORTUNITIES FOR FIELD INVESTIGATIONS RICHARD CLARK Parcey House, Hartsop, Penrith, Cumbria CA11 0NZ AND PETER WILSON School of Environmental Studies, University of Ulster at Coleraine, Cromore Road, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Mosedale is part of the valley of the River Caldew in the Skiddaw upland of the northeastern Lake District. It possesses a diverse, interesting and problematic assemblage of landforms and is convenient to Blencathra Field Centre. The landforms result from glacial, periglacial, fluvial and hillslopes processes and, although some of them have been described previously, others have not. Landforms of one time and environment occur adjacent to those of another. The area is a valuable locality for the field teaching and evaluation of upland geomorphology. In this paper, something of the variety of landforms, materials and processes is outlined for each district in turn. That is followed by suggestions for further enquiry about landform development in time and place. Some questions are posed. These should not be thought of as being the only relevant ones that might be asked about the area: they are intended to help set enquiry off. Mosedale offers a challenge to students at all levels and its landforms demonstrate a complexity that is rarely presented in the textbooks. INTRODUCTION Upland areas attract research and teaching in both earth and life sciences. In part, that is for the pleasure in being there and, substantially, for relative freedom of access to such features as landforms, outcrops and habitats, especially in comparison with intensively occupied lowland areas.