SUPPRESSING CONFESSIONS: INVOLUNTARINESS and MIRANDA by Paul Couenhoven I. a CONFESSION IS INADMISSIBLE AS INVOLUNTARY IF IT IS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRUCTURING the PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe*

STRUCTURING THE PUBLIC DEFENDER Irene Oriseweyinmi Joe* ABSTRACT. The public defender may be critical to protecting individual rights in the U.S. criminal process, but state governments take remarkably different approaches to distributing the services. Some organize indigent defense as a function of the executive branch of state governance. Others administer the services through the judicial branch. The remaining state governments do not place it within any branch of state government, they delegate its management to local counties. This administrative choice has important implications for the public defender’s efficiency and effectiveness. It influences how the public defender will be funded and also the extent to which the public defender, as an institution, will respond to the particular interests of local communities. So, which branch of government should oversee the public defender? Should the public defender exist under the same branch of government that oversees the prosecutor and the police – two entities that the public defender seeks to hold accountable in the criminal process? Should the provision of services be housed under the judicial branch which is ordinarily tasked with being a neutral arbiter in criminal proceedings? Perhaps a public defender who is independent of statewide governance is ideal even if that might render it a lesser player among the many government agencies battling at the state level for limited financial resources. This article answers this question about state assignment by engaging in an original examination of each state’s architectural choices for the public defender. Its primary contribution is to enrich our current understanding of how each state manages the public defender function and how that decision influences the institution’s funding and ability to adhere to ethical and professional mandates. -

International Tribunals and Rules of Evidence: the Case for Respecting and Preserving the "Priest-Penitent" Privilege Under International Law

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 3 Article 3 2000 International Tribunals and Rules of Evidence: The Case for Respecting and Preserving the "Priest- Penitent" Privilege Under International Law Robert John Araujo S.J. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Araujo, S.J., Robert John. "International Tribunals and Rules of Evidence: The asC e for Respecting and Preserving the "Priest-Penitent" Privilege Under International Law." American University International Law Review 15, no. 3 (2000): 639-666. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERNATIONAL TRIBUNALS AND RULES OF EVIDENCE: THE CASE FOR RESPECTING AND PRESERVING THE "PRIEST-PENITENT" PRIVILEGE UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW ROBERT JOHN ARAUJO, S.J." INTRODUCTION .............................................. 640 I. THE PRIEST-PENITENT PRIVILEGE'S ORIGINS ........ 643 II. THE PRIVILEGE AT CIVIL AND COMMON LAW ....... 648 A. EUROPE, CANADA, AUSTRALIA, AND NEW ZEALAND ....... 648 B. THE UNITED STATES ...................................... 657 Ed. THE PRIVILEGE UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW ....... 661 CONCLU SION ................................................. 665 The Lord spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to the Israelites-When a man or woman wrongs another, breaking faith with the Lord, that person in- curs guilt and shall confess the sin that has been committed. The person shall make full restitution for the wrong, adding one fifth to it, and giving it to the one who was wronged!' If we confess our sins, he who is faithful and just will forgive us our sins and cleanse us from all unrighteousness. -

Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases by Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report November 2000, NCJ 179023 Defense Counsel in Criminal Cases By Caroline Wolf Harlow, Ph.D. Highlights BJS Statistician At felony case termination, court-appointed counsel represented 82% Almost all persons charged with a of State defendants in the 75 largest counties in 1996 felony in Federal and large State courts and 66% of Federal defendants in 1998 were represented by counsel, either Percent of defendants ù Over 80% of felony defendants hired or appointed. But over a third of Felons Misdemeanants charged with a violent crime in persons charged with a misdemeanor 75 largest counties the country’s largest counties and in cases terminated in Federal court Public defender 68.3% -- 66% in U.S. district courts had represented themselves (pro se) in Assigned counsel 13.7 -- Private attorney 17.6 -- publicly financed attorneys. court proceedings prior to conviction, Self (pro se)/other 0.4 -- as did almost a third of those in local ù About half of large county jails. U.S. district courts Federal Defender felony defendants with a public Organization 30.1% 25.5% defender or assigned counsel Indigent defense involves the use of Panel attorney 36.3 17.4 and three-quarters with a private publicly financed counsel to represent Private attorney 33.4 18.7 Self representation 0.3 38.4 lawyer were released from jail criminal defendants who are unable to pending trial. afford private counsel. At the end of Note: These data reflect use of defense counsel at termination of the case. -

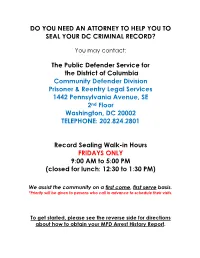

Do You Need an Attorney to Help You to Seal Your Dc Criminal Record?

DO YOU NEED AN ATTORNEY TO HELP YOU TO SEAL YOUR DC CRIMINAL RECORD? You may contact: The Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia Community Defender Division Prisoner & Reentry Legal Services 1442 Pennsylvania Avenue, SE 2nd Floor Washington, DC 20002 TELEPHONE: 202.824.2801 Record Sealing Walk-in Hours FRIDAYS ONLY 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (closed for lunch: 12:30 to 1:30 PM) We assist the community on a first come, first serve basis. *Priority will be given to persons who call in advance to schedule their visits. To get started, please see the reverse side for directions about how to obtain your MPD Arrest History Report. To Get Started First Obtain Your “MPD Arrest History Report for the Purposes of the Criminal Sealing Act of 2006” Before anyone can determine your eligibility to file a motion to seal records and/or arrests, you need to obtain an MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. Five Steps to Obtain Your MPD Arrest History Report 1. Bring with you ALL of the following items: a. A valid government-issued ID (such as a Driver’s License) b. $7.00 cash or money order to pay for the record c. Your social security number 2. Go to the Record Information Desk at the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD), located at 300 Indiana Avenue, NW, Criminal History Section, Room 1075 (On the 1st Floor). a. They are open Mon-Fri from 9:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m. 3. Request a copy of your MPD Arrest History Report for Purposes of the Criminal Record Sealing Act of 2006. -

Confessions of Third Persons in Criminal Cases L

Cornell Law Review Volume 1 Article 3 Issue 2 January 1916 Confessions of Third Persons in Criminal Cases L. A. Wilder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation L. A. Wilder, Confessions of Third Persons in Criminal Cases, 1 Cornell L. Rev. 82 (1916) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol1/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONFESSIONS OF THIRD PERSONS IN CRIMINAL CASES By L. A. WILDER1 Why should a confession of a specific crime, which would be admis- sible against the confessor if he were on trial, be inadmissible in favor of a third person charged with the offense, when the confessor is not available as a witness? No doubt the average layman would declare this state of the law glaringly inconsistent in itself, and wholly incompatible with the professed attitude of criminal courts toward accused persons. And while the general sense of justice in the abstract is not always a true test of justice in the concrete, the fact that it is shocked by the denial to A of the benefit of B's confession, however voluntary and reliable it may be, is sufficient to justify a comment upon the rule which so excludes the confession. Of course, it is understood that the confession (as distinguished from an admission) is admitted in evidence against the confessor by virtue of that exception to the hearsay rule, which lets in declara- tions against the interest of the declarant. -

In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: the Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis V

UIC Law Review Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 3 Winter 2011 In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) Harvey Gee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Harvey Gee, In Order to Be Silent, You Must First Speak: The Supreme Court Extends Davis's Clarity Requirement to the Right to Remain Silent in Berghuis v. Thompkins, 44 J. Marshall L. Rev. 423 (2011) https://repository.law.uic.edu/lawreview/vol44/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Review by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IN ORDER TO BE SILENT, YOU MUST FIRST SPEAK: THE SUPREME COURT EXTENDS DAVIS'S CLARITY REQUIREMENT TO THE RIGHT TO REMAIN SILENT IN BERGHUIS V. THOMPKINS HARVEY GEE* Criminal suspects must now unambiguously invoke their right to remain silent-which, counterintuitively, requires them to speak. .. suspects will be legally presumed to have waived their rights even if they have given clear expression of their intent to do so. Those results ... find no basis in Miranda... 1 I. INTRODUCTION At 3:09 a.m., two police officers escorted Richard Lovejoy, a suspect in an armed bank robbery, into a twelve-foot-square dimly lit interrogation room affectionately referred to as the "boiler room." This room is equipped with a two-way mirror in the wall for viewing lineups. -

Questions and Answers

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 34 | Issue 1 Article 8 1943 Questions and Answers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Questions and Answers, 34 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 43 (1943-1944) This Correspondence is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Questions and Answers David Geeting Monroe (Ed.) Long before the science of criminal investigation came into repute, enforcement officials had come to rely upon the confession as an important means of establishing guilt. The courts, for example, viewed confessions as one of the best and most substantial species of evidence. They assumed, and correctly, that no person in the full possession of his faculties would voluntarily' sacrifice life, liberty, or property by confessing to a crime he did not commit. And from the point of view of the police, the confession offered an invaluable means of disclosing guilt in light of the exceptional difficulties involved in fixing criminality. For crimes in large part are cloaked in secrecy and men conscious of criminal purpose seek to shelter their knavery from the observing eyes of others. Thus, through the ages, the confession has held a significant position in the field of crime repression. Nevertheless, use of confessional evidence has suffered an harrassed and checkered career and on innumerable occasions has obstructed the normal functioning of enforcement. -

A Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System

A GUIDE TO MENTAL ILLNESS AND THE CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM A SYSTEMS GUIDE FOR FAMILIES AND CONSUMERS National Alliance on Mental Illness Department of Policy and Legal Affairs 2107 Wilson Blvd., Suite 300 Arlington, VA 22201 Helpline: 800-950-NAMI NAMI – Guide to Mental Illness and the Criminal Justice System FOREWORD Tragically, jails and prisons are emerging as the "psychiatric hospitals" of the 1990s. A sample of 1400 NAMI families surveyed in 1991 revealed that 40 percent of family members with severe mental illness had been arrested one or more times. Other national studies reveal that approximately 8 percent of all jail and prison inmates suffer from severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. These statistics are a direct reflection of the failure of public mental health systems to provide appropriate care and treatment to individuals with severe mental illnesses. These horrifying statistics point directly to the need of NAMI families and consumers to develop greater familiarity with the workings of their local criminal justice systems. Key personnel in these systems, such as police officers, prosecutors, public defenders and jail employees may have limited knowledge about severe mental illness and the needs of those who suffer from these illnesses. Moreover, the procedures, terminology and practices which characterize the criminal justice system are likely to be bewildering for consumers and family members alike. This guide is intended to serve as an aid for those people thrust into interaction with local criminal justice systems. Since criminal procedures are complicated and often differ from state to state, readers are urged to consult the laws and procedures of their states and localities. -

Cross Examining Police in False Confession Cases By: Attorney Deja Vishny*

The WISCONSIN Winter/Spring 2008 DEFENDER Volume 16, Issue 1 Cross Examining Police in False Confession Cases By: Attorney Deja Vishny* Many criminal defense lawyers are filled with dread at the idea of trying a confession case. We think the jury will never accept that people give false confessions. We worry that jurors and courts will always believe that because our clients gave a recorded confession, they must have committed the crime. Our experience in motion litigation has taught us that judges rarely, if ever, take the risk of suppressing the confession particularly when a crime is horrifying and highly publicized. Since the advent of mandatory recorded interrogation in juvenile and felony cases we have been lucky enough to be able to listen to the recording and pinpoint exactly how law enforcement agents are able to get our clients to confess. No longer is the process of getting a confession shrouded in mystery as the police enter into a closed off locked room with a suspect who is determined to maintain their innocence and emerge hours (sometimes days) later with a signed statement that proclaims “I did it”. However, defense lawyers listening to the tapes must be able to appreciate the significance of what is being said to cajole a confession. The lawyer handling a recorded interrogation case should always listen carefully to the recording of the entire interrogation as early as possible in the case. There have been many occasions of discrepancies between how a police officer will characterize the confession in testimony or a written report from how the statement was actually developed and what the tape shows the client’s actual words were. -

Criminal Law-Evidence--Confession to Polygraph Operator Prior to Actual Test Held Admissible

University of Richmond Law Review Volume 9 | Issue 2 Article 13 1975 Criminal Law-Evidence--Confession to Polygraph Operator Prior to Actual Test Held Admissible Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Criminal Law-Evidence--Confession to Polygraph Operator Prior to Actual Test Held Admissible, 9 U. Rich. L. Rev. 377 (1975). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/lawreview/vol9/iss2/13 This Recent Decision is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Richmond Law Review by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Criminal Law-Evidence-CONFESSION TO POLYGRAPH OPERATOR PRIOR TO ACTUAL TEST HELD ADMISSIBLE-Jones v. Commonwealth, 214 Va. 723, 204 S.E.2d 247 (1974). Rules of evidence governing the admissibility of confessions have devel- oped gradually throughout the history of Anglo-American jurisprudence. Initially any confession was admissible regardless of the methods by which it was obtained.' The basic consideration was that the evidence admitted be truthful and reliable. 2 To protect the integrity of judicial proceedings, safeguards were later developed to insure the reliability of confessions by a determination of the voluntariness with which they were given.3 Courts have struggled with the problem of formulating a workable definition of voluntariness and have not yet developed a uniform substantive test.' Several procedures have been developed to provide for a determination of the voluntariness of a confession.' Virginia follows the "Wigmore" or 1. -

Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin

Marquette Law Review Volume 91 Issue 1 Symposium: Dispute Resolution in Criminal Article 16 Law Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Plea Bargaining from the Criminal Lawyer's Perspective: Plea Bargaining in Wisconsin, 91 Marq. L. Rev. 357 (2007). Available at: http://scholarship.law.marquette.edu/mulr/vol91/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marquette Law Review by an authorized administrator of Marquette Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PANEL DISCUSSION PLEA BARGAINING FROM THE CRIMINAL LAWYER'S PERSPECTIVE: PLEA BARGAINING IN WISCONSIN* PANELISTS E. Michael McCann FormerDistrict Attorney, Milwaukee County; Boden Teaching Fellow & Adjunct Professor of Law, Marquette UniversityLaw School Michelle Jacobs FirstAssistant United States Attorney, Eastern Districtof Wisconsin Erik Peterson United States Attorney, Western Districtof Wisconsin Dean Strang Hurley, Burish & Stanton, S.C. Nathan Fishbach Whyte Hirschboeck Dudek S. C. Deja Vishny Office of the Wisconsin State Public Defender MODERATOR Daniel D. Blinka Professorof Law, Marquette University Law School This panel discussion was held as part of the Conference on Plea Bargaining on April 14, 2007, at Marquette University Law School. The transcript of the Panel Discussion has been lightly edited. MARQUETTE LAW REVIEW [91:357 The primary purpose of the Conference is to present diverse views on plea bargaining. In addition to the articles, which represent varying academic and policy perspectives, we have assembled a panel of criminal law practitioners to contribute their insights and experience. -

Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 5 Article 4 1915 Necessity for a Public Defender Mayer C. Goldman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Mayer C. Goldman, Necessity for a Public Defender, 5 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 660 (May 1914 to March 1915) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE NECESSITY FOR A PUBLIC DEFENDER MAYE C. GOLDMAN' Among the grave legal and sociological reforms which are being seriously urged at present by thinking people, there is being actively agitated the important proposition of creating the office of a Public Defender to defend indigent persons accused of crime. If by the establishment of such an office, the standard of our criminal jurisprudence can be raised and the principles of human justice thereby placed upon a more solid foundation, the inevitable result thereof must be, that the suspicion now lurking in the public mind to the effect that a discrimination exists between the rich and the poor, must give way to a wholesome realization of the fact that our much vaunted theory of "equality before the law" has become an actuality-instead of a mere high-sounding phrase. It must be apparent to all, that the important consideration in the trial of any cause, is, (or ought to be) to ascertain the truth- and not a mere contest in which one side or the other is permitted to gain an advantage by superior strategy, skill or power.