Modeling Ethnic and Religious Diversity in Myanmar Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: to Be a Modern Burmese Citizen Living in a Nation‐State, 1889 – 1962

Shwe U Daung and the Burmese Sherlock Holmes: To be a modern Burmese citizen living in a nation‐state, 1889 – 1962 Yuri Takahashi Southeast Asian Studies School of Languages and Cultures Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney April 2017 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Statement of originality This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources has been acknowledged. Yuri Takahashi 2 April 2017 CONTENTS page Acknowledgements i Notes vi Abstract vii Figures ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Biography Writing as History and Shwe U Daung 20 Chapter 2 A Family after the Fall of Mandalay: Shwe U Daung’s Childhood and School Life 44 Chapter 3 Education, Occupation and Marriage 67 Chapter ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1917 and 1930 88 Chapter 5 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1930 and 1945 114 Chapter 6 ‘San Shar the Detective’ and Burmese Society between 1945 and 1962 140 Conclusion 166 Appendix 1 A biography of Shwe U Daung 172 Appendix 2 Translation of Pyone Cho’s Buddhist songs 175 Bibliography 193 i ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I came across Shwe U Daung’s name quite a long time ago in a class on the history of Burmese literature at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. -

Research Impact of Pāli on the Development of Myanmar Literature

Journal homepage: http://twasp.info/journal/home Research Impact of Pāli on the Development of Myanmar Literature Dr- Tin Tin New1*, Yee Mon Phay2, Dr- Minn Thant3 1Professor, Department of Oriental Studies, Mandalay University, Mandalay, Myanmar 2PhD Candidate, School of Liberal Arts, Department of Global Studies, Shanghai University, Shanghai, China 3Lecturer, Department of Oriental Studies, Mandalay University, Myanmar *Corresponding author Accepted:19 August, 2019 ;Online: 25 August, 2019 DOI : https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3377041 Abstract Buddhism introduced Myanmar since the first century AD and there prospered in about 4th to 5th century AD in Śriksetra (Hmawza, Pyay), Suvannabhūmi (Thaton), Rakhine and Bagan. Since that time, people of Myanmar made their effort to develop and prosper Buddhism having studied Pāli, the language of Theravāda Buddhism. In Bagan period, they attempted to create Burmese scripts and writing system imitating to Pāli. From that time Myanmar Literature gradually had been developed up to present. In this paper it is shed a light about influence of Pāli on Myanmar Literature. Keywords Burmese literature, Ancient literature. Impact of Pāli on the Development of Myanmar Literature Literary and archaeological sources as founded in Śriksetra (Hmawza, Pyay), Suvannabhūmi (Thaton), Rakhine and Bagan proved that Buddhism introduced Myanmar since the first century AD and there prospered in about 4th to 5th century AD. Pyu people recorded Pāli extracts in Pyu scripts, Mon also recorded Pāli in their own scripts and Myanmar recorded Pāli in Myanmar script. In this way, people of Myanmar made their effort to develop and prosper Buddhism having studied Pāli, the language of Theravāda Buddhism. -

Refugees from Burma Acknowledgments

Culture Profile No. 21 June 2007 Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences Writers: Sandy Barron, John Okell, Saw Myat Yin, Kenneth VanBik, Arthur Swain, Emma Larkin, Anna J. Allott, and Kirsten Ewers RefugeesEditors: Donald A. Ranard and Sandy Barron From Burma Published by the Center for Applied Linguistics Cultural Orientation Resource Center Center for Applied Linguistics 4646 40th Street, NW Washington, DC 20016-1859 Tel. (202) 362-0700 Fax (202) 363-7204 http://www.culturalorientation.net http://www.cal.org The contents of this profile were developed with funding from the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, United States Department of State, but do not necessarily rep- resent the policy of that agency and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government. This profile was published by the Center for Applied Linguistics (CAL), but the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of CAL. Production supervision: Sanja Bebic Editing: Donald A. Ranard Copyediting: Jeannie Rennie Cover: Burmese Pagoda. Oil painting. Private collection, Bangkok. Design, illustration, production: SAGARTdesign, 2007 ©2007 by the Center for Applied Linguistics The U.S. Department of State reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the work for Government purposes. All other rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to the Cultural Orientation Resource Center, Center for Applied Linguistics, 4646 40th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20016. -

Interpreting Myanmar a Decade of Analysis

INTERPRETING MYANMAR A DECADE OF ANALYSIS INTERPRETING MYANMAR A DECADE OF ANALYSIS ANDREW SELTH Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464042 ISBN (online): 9781760464059 WorldCat (print): 1224563457 WorldCat (online): 1224563308 DOI: 10.22459/IM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Yangon, Myanmar by mathes on Bigstock. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Acronyms and abbreviations . xi Glossary . xv Acknowledgements . xvii About the author . xix Protocols and politics . xxi Introduction . 1 THE INTERPRETER POSTS, 2008–2019 2008 1 . Burma: The limits of international action (12:48 AEDT, 7 April 2008) . 13 2 . A storm of protest over Burma (14:47 AEDT, 9 May 2008) . 17 3 . Burma’s continuing fear of invasion (11:09 AEDT, 28 May 2008) . 21 4 . Burma’s armed forces: How loyal? (11:08 AEDT, 6 June 2008) . 25 5 . The Rambo approach to Burma (10:37 AEDT, 20 June 2008) . 29 6 . Burma and the Bush White House (10:11 AEDT, 26 August 2008) . 33 7 . Burma’s opposition movement: A house divided (07:43 AEDT, 25 November 2008) . 37 2009 8 . Is there a Burma–North Korea–Iran nuclear conspiracy? (07:26 AEDT, 25 February 2009) . 43 9 . US–Burma: Where to from here? (14:09 AEDT, 28 April 2009) . -

The Influence of Burmese Buddhist Understandings of Suffering on the Subjective Experience and Social Perceptions of Schizophrenia

THE INFLUENCE OF BURMESE BUDDHIST UNDERSTANDINGS OF SUFFERING ON THE SUBJECTIVE EXPERIENCE AND SOCIAL PERCEPTIONS OF SCHIZOPHRENIA by SARAH ELIZABETH ADLER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Melvyn C. Goldstein Department of Anthropology CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY January 2008 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of ______________________________________________________ candidate for the ________________________________degree *. (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Tables v Acknowledgements vi Abstract vii I. Introduction 1 A. Models and Meaning of Therapeutic Efficacy 2 B. The Role of Religion in Addressing Health Concerns 6 C. Suffering: Connecting Religion and Illness Experience 10 D. The Definition and Cultural Construction of Suffering 13 E. Religion and Suffering in the Context of Schizophrenia 18 F. Buddhism, Suffering, and Healing 22 G. Summary of Objectives and Outline of the Dissertation 28 II. Research Design and Methods 30 A. Development of Topic and Perspective 30 B. Research Site 33 1. Country Profile 33 2. Yangon Mental Health Hospital 37 3. Outpatient Clinics 45 4. Community 48 C. Research Participants 49 1. Patient subset (n=40; 20 inpatients, 20 outpatients) 52 2. Family member subset (n=20) 56 3. Healer subset (n=40) 57 4. Survey respondents (n=142) 59 D. Interpretation and Analysis 60 1. Data Collection 60 a. Structured Interviews 62 b. Semi-Structured Interviews 66 c. -

4 April 2021 1 4 April 21 Gnlm

EMPHASIZE PHYSICAL AND MENTAL WELL-BEING OF PEOPLE PAGE-8 (OPINION) Vol. VII, No. 353, 8th Waning of Tabaung 1382 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Sunday, 4 April 2021 Tatmadaw will strive for a genuine, disciplined and concrete democracy: Senior General Chairman of the State Administration Council Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services Senior General Min Aung Hlaing meets officers, other ranks and families of Meiktila Station yesterday. CHAIRMAN of the State Ad- election frauds, and instead, there The person one voted would elect ministration Council Command- were even attempts to convene the leaders of the State on his er-in-Chief of Defence Services the third Hluttaw and to take behalf, in the respective Hluttaws. Senior General Min Aung Hlaing over the respective branches of So, the elected person must be a The country’s democracy is just yesterday afternoon separate- State power by force. Hence, the true representative of the people. ly met officers, other ranks and Tatmadaw had to declare the During the election, Tatmadaw nascent. Therefore, some power- families of Meiktila Station. state of emergency and tempo- members ardently cast votes in Present at the meeting to- rarily shoulder the duties of the accord with the rules and under ful countries and organizations gether with the Senior General State transferred to it by the act- the systematic programmes ar- were members of the Council ing president. In every place he ranged by the Tatmadaw. attempted to import democracy General Maung Maung Kyaw, visited during the post-election Election is the essence of de- they wanted under various titles Lt-Gen Moe Myint Tun, Joint Sec- period, the Senior General spoke mocracy. -

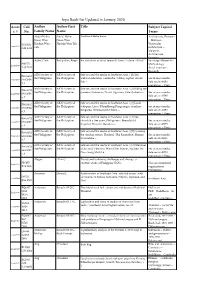

Inya Book-List Updated in January 2020

Inya Book-list Updated in January 2020 Acces Call Author Author First Title Subject Topical s. # No. Family Name Name Terms Abdul Halim Abdul Halim Traditional Malay house Architecture, Domestic Nasir, Wan Nasir, Wan -- Malaysia. NA7436 . Hashim Wan Hashim Wan Teh. Vernacular Inya-0335 A24 1996 Teh. architecture -- Malaysia. Architecture, Domestic. Adler; Clark Emily Stier; Roger An invitation to social research : how it's done / 4th ed Sociology--Research-- HM571 . Methodology. Inya-0399 A35 2011 Social sciences-- Research-- AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [1] Sex Methodology. P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. without substance, Cambodia / Chhay Sophal, Steven Sex in mass media. Inya-0283 S68 2004 Pak -- Safe sex in AIDS v.1 prevention -- Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [2] Riding the coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. paradox, Indonesia / Nurul Agustina, Irwan Julianto -- Asia.Sex in mass media. Inya-0410 S68 2004 SexualSafe sex health in AIDS -- Press v.2 coverageprevention -- --Southeast Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [3] Loud Asia.coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. whispers, Laos / Khamkhong Kongvongsa, Somkiao Asia.Sex in mass media. Inya-0411 S68 2004 Kingsada, Phonesavanh Thikeo -- SexualSafe sex health in AIDS -- Press v.3 coverageprevention -- --Southeast Press AIDS Society of AIDS Society of Safe sex and the media in Southeast Asia. / [4] Sex, Asia.coverage -- Southeast P96.S452 the Philippines. the Philippines. church & a free press, Philippines / Reynaldo H. -

Burma Project T 080830

Burma / Myanmar Bibliographical Project Siegfried M. Schwertner Bibliographic description TTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT T., H. H. Table of conversion, village to standard baskets, Myigun Tilre, H. H. Township, Magwe District [/ signed by W. J. Baker]. – Rangoon : Govt. Print., Burma (for D. L. R. and A.), 1904. T.C.A. 30 p. – Added title and text in Burmese United States / Department of State / Technical GB: BL(14300 gg 9(2))* Cooperation Administration Table of conversion, village to standard baskets, Myothit T.R.C. Township, Magwe District [/ signed by W. J. Baker ]. – Thailand Revolutionary Council Rangoon : Govt. Print., Burma (for D. L. R. and A.), 1904. 9 p. Ta Van Tai <b. 1938> Added title and text in Burmese The role of the military in the developing nations of South GB: BL(14300 gg 9(3))* and Southeast Asia : with special reference to Pakistan, Burma and Thailand / by Ta Van Tai. – 1965. 555 l., tables, Table of conversion, village to standard baskets, Natmauk app., notes, bibliogr. l. 532-555. – Charlottesville, Va., Univ. Township, Magwe District [/ signed by W. J. Baker]. – of Virginia, Ph.D. (political science, international law and Rangoon : Govt. Print., Burma (for D. L. R. and A.), 1904. relations), thesis 1965. – DissAb 26.9, 1966, 5536. - Shul- 25 p. man 602. Added title and text in Burmese UMI 66-03208 GB: BL(14300 gg 9(4))* Subject(s): Burma : Armed forces - Political activities ; Newly independent states - Politics and government ; Table of conversion, village to standard baskets, Taung- Politics and government <1948-> dwingyi Township, Magwe District [/ signed by W. J. AU:ANU(Chifley JQ1755.T3) Baker]. -

Title Author First Name Author Family Name

Accessio Author Family Call No. Title Author First Name Subject Topical Terms n No. Name Architecture, Domestic -- Malaysia. Abdul Halim Nasir, Abdul Halim Nasir, Vernacular architecture -- Malaysia. NA7436 Inya-0335 Architecture, Domestic. .A24 1996 Traditional Malay house Wan Hashim Wan Wan Hashim Wan Teh. Teh. Weighing the balance : Southeast Southeast Asia--Study and teaching (Higher)--United States--Congresses. Asian studies ten years after : DS524.8.U6 Inya-0346 W45 2000 proceedings of two meetings held in Itty Abraham New York City, November 15 and December 10, 1999. An invitation to social research : how Sociology--Research--Methodology. Social sciences--Research--Methodology. HM571 Inya-0399 it's done / 4th ed .A35 2011 Emily Stier and Roger Adler and Clark Safe sex and the media in Southeast Sex in mass media. Safe sex in AIDS prevention -- Press coverage -- P96.S452 Asia. / [1] Sex without substance, AIDS Society of the AIDS Society of the Inya-0283 Southeast Asia. S68 2004 v.1 Cambodia / Chhay Sophal, Steven Pak Philippines. Philippines. Sexual health -- Press coverage -- Southeast Asia. Safe sex and the media in Southeast Sex in mass media. Safe sex in AIDS prevention -- Press coverage -- P96.S452 Asia. / [2] Riding the paradox, AIDS Society of the AIDS Society of the Inya-0410 Southeast Asia. S68 2004 v.2 Indonesia / Nurul Agustina, Irwan Philippines. Philippines. Sexual health -- Press coverage -- Southeast Asia. Julianto Safe sex and the media in Southeast Sex in mass media. Safe sex in AIDS prevention -- Press coverage -- P96.S452 Asia. / [3] Loud whispers, Laos / AIDS Society of the AIDS Society of the Inya-0411 Southeast Asia. -

THE BIBLIOGRAPHY of BURMA (MYANMAR) RESEARCH: the SECONDARY LITERATURE (2004 Revision)

SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research Bibliographic Supplement (Winter, 2004) ISSN 1479- 8484 THE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF BURMA (MYANMAR) RESEARCH: THE SECONDARY LITERATURE (2004 Revision) Michael Walter Charney (comp.)1 School of Oriental and African Studies “The ‘Living’ Bibliography of Burma Studies: The Secondary Literature” was first published in 2001, with the last update dated 26 April 2003. The SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research has been expanded to include a special bibliographic supplement this year, and every other year hereafter, into which additions and corrections to the bibliography will be incorporated. In the interim, each issue of the SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research will include a supplemental list, arranged by topic and sub- topic. Readers are encouraged to contact the SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research with information about their publications, hopefully with a reference to a topic and sub-topic number for each entry, so that new information can be inserted into the bibliography correctly. References should be submitted in the form followed by the bibliography, using any of the entries as an example. Please note that any particular entry will only be included once, regardless of wider relevance. Eventually, all entries will be cross-listed to indicate other areas where a particular piece of research might be of use. This list has been compiled chiefly from direct surveys of the literature with additional information supplied by the bibliographies of numerous and various sources listed in the present bibliography. Additional sources include submissions from members of the BurmaResearch (including the former Earlyburma) and SEAHTP egroups, as well as public domain listings of personal publications on the internet. -

THE PALI LITERATURE Or BURMA

ABBREVIATIONS ’ ’ ’ B ull tin de l Eeole Fran aise d Ex rém r BEF . e t e O ient EO p . e t c 1901 , . dhava sa. 1886 . Inde x 1 89 6 Gan . m (J , h Pali Text Societ Journa l o t e . Lo do 1882 e t c f y n n . , . u rnal o the Ro a l Asiatic Societ Lo do Jo f y y. n n. ham ain . R o o 1906 kat t . Pita ang n . o Pali Text S ciety. nava sadi a. Co o o . 1881 Sesa m p l mb . BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES Students m ay consult with advantage ’ I The o of t he So l o for t he o d , wh le Pali Text ciety s pub icati ns ( l er Pali e Frowde . Lo do 1 882 et c . lit rature) . n n, , o of the d in o II. Translati ns same which have appeare vari us languages Mr. Ed se e the s io of o on B dd b . ds ( u eful bibl graphy w rks u hism, y A J mun , in t he o of the So J urnal Pali Text ciety, Particularly interesting for c omparison of Burmese versi ons with i are t he o o f at akas o m the B e b Mr. R. Pal translati ns J fr urm se, y F d S o in the o of t he Ro A So St . t An rew . J hn, J urnal yal siatic ciety, Cf the a a he s 1892 1 893 1 894 1 896 . -

The Life and Writings of a Patriotic Feminist: Independent Daw San of Burma

The Life and Writings of a Patriotic Feminist 23 chapter 1 The Life and Writings of a Patriotic Feminist: Independent Daw San of Burma Chie Ikeya Introduction Throughout Southeast Asia, the 1920s and 1930s witnessed a marked intensification in reformist, anti-colonial and nationalist activities. In Burmese history this period of late colonialism marks a watershed, when disparate political developments — party politics, university boycotts, labour strikes and nonviolent protests — emerged to signify a new kind of nain ngan yay (politics) and the birth of the wunthanu (protector of national interests) movement. In 1920, a faction led by young members of the Young Men’s Buddhist Association (YMBA), the most famous and influential lay Buddhist organisation in colonial Burma,1 formed the General Council of Burmese Associations (GCBA), the first organisation with explicitly political goals that focused on securing representative political rights. Within a few years, the GCBA had 12,000 branches throughout Burma.2 Buddhist monks also involved themselves in political activity and played a key role in the formation of wunthanu athin or village-level “patriotic associations” that advocated non-cooperation with the British government in various forms, such as refusal to pay taxes, defiance of orders of the village headmen, boycott of foreign goods, and use of indigenous goods. Despite government attempts to suppress the activities of poli- tical monks throughout the 1920s, wunthanu athin developed into influential political institutions in the countryside,