Download (7Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xx:2 Dr. Mabuse 1933

January 19, 2010: XX:2 DAS TESTAMENT DES DR. MABUSE/THE TESTAMENT OF DR. MABUSE 1933 (122 minutes) Directed by Fritz Lang Written by Fritz Lang and Thea von Harbou Produced by Fritz Lanz and Seymour Nebenzal Original music by Hans Erdmann Cinematography by Karl Vash and Fritz Arno Wagner Edited by Conrad von Molo and Lothar Wolff Art direction by Emil Hasler and Karll Vollbrecht Rudolf Klein-Rogge...Dr. Mabuse Gustav Diessl...Thomas Kent Rudolf Schündler...Hardy Oskar Höcker...Bredow Theo Lingen...Karetzky Camilla Spira...Juwelen-Anna Paul Henckels...Lithographraoger Otto Wernicke...Kriminalkomissar Lohmann / Commissioner Lohmann Theodor Loos...Dr. Kramm Hadrian Maria Netto...Nicolai Griforiew Paul Bernd...Erpresser / Blackmailer Henry Pleß...Bulle Adolf E. Licho...Dr. Hauser Oscar Beregi Sr....Prof. Dr. Baum (as Oscar Beregi) Wera Liessem...Lilli FRITZ LANG (5 December 1890, Vienna, Austria—2 August 1976,Beverly Hills, Los Angeles) directed 47 films, from Halbblut (Half-caste) in 1919 to Die Tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse (The Thousand Eye of Dr. Mabuse) in 1960. Some of the others were Beyond a Reasonable Doubt (1956), The Big Heat (1953), Clash by Night (1952), Rancho Notorious (1952), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Scarlet Street (1945). The Woman in the Window (1944), Ministry of Fear (1944), Western Union (1941), The Return of Frank James (1940), Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (The Crimes of Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Mabuse's Testament, There's a good deal of Lang material on line at the British Film The Last Will of Dr. Mabuse, 1933), M (1931), Metropolis Institute web site: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/lang/. -

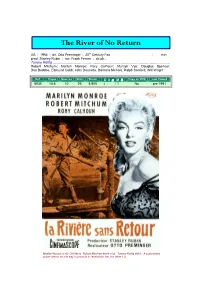

The River of No Return

The River of No Return US : 1954 : dir. Otto Preminger : 20th Century Fox : min prod: Stanley Rubin : scr: Frank Fenton : dir.ph.: Tommy Rettig …..……….……………………………………………………………………………… Robert Mitchum; Marilyn Monroe; Rory Calhoun; Murvyn Vye; Douglas Spencer; Don Beddoe, Edmund Cobb, John Doucette, Barbara Nichols, Ralph Sanford, Will Wright Ref: Pages Sources Stills Words Ω 8 M Copy on VHS Last Viewed 5935 10.5 10 25 5,905 - - No pre 1991 Marilyn Monroe in the Old West. Robert Mitchum drank a lot. Tommy Rettig didn’t. A sepia-tinted poster seems an odd way to promote a Technicolor film, but there it is. People who drink fall over a lot. This is a proven fact. Source: indeterminate Excerpt from The Moving Picture Boy entry Calhoun) and his companion Kay Weston on Nirumand, who starred the previous year in (Monroe). After Calder rescues them from Naderi's “DAWANDEH” (or “The Runner”): the wild river, Weston robs them, and leaves everyone to die. Calder goes after “He kept on running in Naderi's "AAB, him, but is a little puzzled as to why Kay BAAD, KHAK", a drama of drought set in the would remain so loyal to the liar and cheat, parched land of the Iranian-Afghan border. while his son, pulling a “COURTSHIP OF But the Iranian authorities, who had already EDDIE’S FATHER”, tries to get the man castigated "DAWANDEH" as a slur on their and woman together. country, and had failed to get Naderi to The movie is the western equivalent of a apologise for it, now banned the showing of "road film", with Calder and Co. -

MASCULINITY AS SPECTACLE REFLECTIONS on MEN and MAINSTREAM CINEMA by STEVE NEALE Downloaded From

MASCULINITY AS SPECTACLE REFLECTIONS ON MEN AND MAINSTREAM CINEMA BY STEVE NEALE Downloaded from http://screen.oxfordjournals.org/ OVER THE PAST ten years or so, numerous books and articles 1 Laura Mulvey, have appeared discussing the images of women produced and circulated 'Visual Pleasure by the cinematic institution. Motivated politically by the development and Narrative Cinema', Screen of the Women's Movement, and concerned therefore with the political Autumn 1975, vol and ideological implications of the representations of women offered by at Illinois University on July 18, 2014 16 no 3, pp 6-18. the cinema, a number of these books and articles have taken as their basis Laura Mulvey's 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema', first published in Screen in 1975'. Mulvey's article was highly influential in its linking together of psychoanalytic perspectives on the cinema with a feminist perspective on the ways in which images of women figure within main- stream film. She sought to demonstrate the extent to which the psychic mechanisms cinema has basically involved are profoundly patriarchal, and the extent to which the images of women mainstream film has produced lie at the heart of those mechanisms. Inasmuch as there has been discussion of gender, sexuality, represen- tation and the cinema over the past decade then, that discussion has tended overwhelmingly to centre on the representation of women, and to derive many of its basic tenets from Mulvey^'s article. Only within the Gay Movement have there appeared specific discussions of the represen- tation of men. Most of these, as far as I am aware, have centred on the representations and stereotypes of gay men. -

Radio TV Mirror

JANICE GILBERT The girl who gave away MIRRO $3,000,000! ARTHUR GODFREY BROOK BYRON BETTY LU ANN SIMMS ANN GROVE ! ^our new Lilt home permaTient will look , feel and stay like the loveliest naturally curly hair H.1 **r Does your wave look as soft and natural as the Lilt girl in our picture? No? Then think how much more beautiful you can be, when you change to Lilt with its superior ingredients. You'll be admired by men . envied by women ... a softer, more charming you. Because your Lilt will look, feel and stay like naturally curly hair. Watch admiring eyes light up, when you light up your life with a Lilt. $150 Choose the Lilt especially made for your type of hair! plus tax Procter £ Gambles new Wt guiJ. H Home Permanent tor hard-to-wave hair for normal hair for easy-to-wave hair for children's hair — . New, better way to reduce decay after eating sweets Always brush with ALL- NEW IPANA after eating ... as the Linders do . the way most dentists recommend. New Ipana with WD-9 destroys tooth-decay bacteria.' s -\V 77 If you eat sweet treats (like Stasia Linder of Massa- Follow Stasia Linder's lead and use new Ipana regularly pequa, N. Y., and her daughter Darryl), here's good news! after eatin g before decay bacteria can do their damage. You can do a far better job of preventing cavities by Even if you can't always brush after eating, no other brushing after eatin g . and using remarkable new Ipana tooth paste has ever been proved better for protecting Tooth Paste. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Have Gun, Will Travel: the Myth of the Frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall

Feature Have gun, will travel: The myth of the frontier in the Hollywood Western John Springhall Newspaper editor (bit player): ‘This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, we print the legend’. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (dir. John Ford, 1962). Gil Westrum (Randolph Scott): ‘You know what’s on the back of a poor man when he dies? The clothes of pride. And they are not a bit warmer to him dead than they were when he was alive. Is that all you want, Steve?’ Steve Judd (Joel McCrea): ‘All I want is to enter my house justified’. Ride the High Country [a.k.a. Guns in the Afternoon] (dir. Sam Peckinpah, 1962)> J. W. Grant (Ralph Bellamy): ‘You bastard!’ Henry ‘Rico’ Fardan (Lee Marvin): ‘Yes, sir. In my case an accident of birth. But you, you’re a self-made man.’ The Professionals (dir. Richard Brooks, 1966).1 he Western movies that from Taround 1910 until the 1960s made up at least a fifth of all the American film titles on general release signified Lee Marvin, Lee Van Cleef, John Wayne and Strother Martin on the set of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance escapist entertainment for British directed and produced by John Ford. audiences: an alluring vision of vast © Sunset Boulevard/Corbis open spaces, of cowboys on horseback outlined against an imposing landscape. For Americans themselves, the Western a schoolboy in the 1950s, the Western believed that the western frontier was signified their own turbulent frontier has an undeniable appeal, allowing the closing or had already closed – as the history west of the Mississippi in the cinemagoer to interrogate, from youth U. -

Chorverbandes Der Pfalz Chorverband 4/2018 Der Pfalz Jaugust · Nr

Juli /August 2018 Zeitschrift des Chorverbandes der Pfalz Chorverband 4/2018 der Pfalz JAugust · Nr. / Juli ChorChor Datenschutz im Chorverband Chorleiterfortbildung Die wichtigsten Infos anschaulich Hospitation beim Jugend- Pfalz Pfalz erklärt – Bericht von PfalzPfalzPfalzMusical-Festival 2018 Dieter Meyer in der Festhalle Herxheim Chor Chor 1 Foto: © Klaus Eichenlaub P 21615 · 1,60 EUR Chor 4/ 2018 Juli /August 2018 Pfalz Wo wende ich mich hin? Thema zuständig Ambulante Stimmbildung Gudrun Scherrer, Am Rauhen Weg 9, Die Carusos, und was damit zusam- 67722 Winnweiler, Tel. (0 63 02) 31 79, Fax Impressum menhängt (0 63 02) 98 33 55, [email protected] Die ChorPfalz ist die Zeitschrift des Chor- verbandes der Pfalz und erscheint alle zwei Begutachtungskonzerte / Seminar Verbandschorleiter Jürgen Schumacher, Monate mit sechs Ausgaben im Jahr. ISSN-Nr. 1614-2861 Chorleitung, musikalische Fragen, Erlenweg 16, 67269 Grünstadt, Tel./Fax Gedruckte Auflage: 2930 Chor-Akademie (musikalisch) u. a. (0 63 59) 86 07 04, [email protected] Verkaufte Auflage: 2 830 Beiträge, finanzielle Angelegenheiten Schatzmeister Eberhard Schwenck, Am weißen Herausgeber, Verlag und Anzeigen: Chorverband der Pfalz Haus 21a, 67435 Neustadt, Tel. (0 63 21) 6 89 26, im Deutschen Chorverband e.V. Fax (0 63 21) 6 67 74, [email protected] Geschäftsstelle: Am Turnplatz 7 76879 Essingen ChorAkademie (organisatorisch), Verbandsmanagement Fon: 0 63 47– 98 28 34 und 98 28 37 Fax: 0 63 47–98 28 77 OVERSO [OnlineVereinsOrgani- Katharina und Werner Mattern, E-Mail: [email protected] sation], Seminare Qualifizierung Neckarstraße 31, 67117 Limburgerhof, Internet: www.chorverband-der-pfalz.de von Chorsängern/-sängerinnen und Tel. -

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May Be Used for Personal Purporses Only Or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 Associated to Dandelon.Com Network

Fritz Lang © 2008 AGI-Information Management Consultants May be used for personal purporses only or by Reihe Filmlibraries 7 associated to dandelon.com network. Mit Beiträgen von Frieda Grafe Enno Patalas Hans Helmut Prinzler Peter Syr (Fotos) Carl Hanser Verlag Inhalt Für Fritz Lang Einen Platz, kein Denkmal Von Frieda Grafe 7 Kommentierte Filmografie Von Enno Patalas 83 Halbblut 83 Der Herr der Liebe 83 Der goldene See. (Die Spinnen, Teil 1) 83 Harakiri 84 Das Brillantenschiff. (Die Spinnen, Teil 2) 84 Das wandernde Bild 86 Kämpfende Herzen (Die Vier um die Frau) 86 Der müde Tod 87 Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler 88 Die Nibelungen 91 Metropolis 94 Spione 96 Frau im Mond 98 M 100 Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse 102 Liliom 104 Fury 105 You Only Live Once. Gehetzt 106 You and Me [Du und ich] 108 The Return of Frank James. Rache für Jesse James 110 Western Union. Überfall der Ogalalla 111 Man Hunt. Menschenjagd 112 Hangmen Also Die. Auch Henker sterben 113 Ministry of Fear. Ministerium der Angst 115 The Woman in the Window. Gefährliche Begegnung 117 Scarlet Street. Straße der Versuchung 118 Cloak and Dagger. Im Geheimdienst 120 Secret Beyond the Door. Geheimnis hinter der Tür 121 House by the River [Haus am Fluß] 123 American Guerrilla in the Philippines. Der Held von Mindanao 124 Rancho Notorious. Engel der Gejagten 125 Clash by Night. Vor dem neuen Tag 126 The Blue Gardenia. Gardenia - Eine Frau will vergessen 128 The Big Heat. Heißes Eisen 130 Human Desire. Lebensgier 133 Moonfleet. Das Schloß im Schatten 134 While the City Sleeps. -

Les Pel·Lícules Del Mes De Juny Il Les SU Hores Licle Einem I Tren (Amo ¡A Cellaberaciú Ie Sfiji I Lenselieria ¿Ubres Publiques

37 Les pel·lícules del mes de juny Il les SU hores licle einem i tren (amo ¡a cellaberaciú ie SfIJI i lenselieria ¿Ubres Publiques. Habitatge i Transferts) 11 DE JUNY 25 DE JUNY EL EXPRESO DE ASALTO Y ROBO AL TREN SHANGHAI (VOSE) mariene Nacionalitat i any de produc ció: EUA, 1932 Títol original: Shanghai dfetrich Express Producció: Paramount Direcció: Josef Von Sternberg Guió: Jules Furthman i Josef Von Sternberg Fotografía: Lee Garmes Música: W. Frankie Harling Intèrprets: Marlene Dietrich, Nacionalitat i any de producció: EUA, 1903 Clive Brook, Anna May Títol original: The Great Train Robbery Wong, Warner Oland. Producció: Thomas Edison Company Direcció: Edwin Stanton Porter Guió: Edwin Stanton Porter w VE. ^ Intèrprets: George Barnes, Broncho Billy Anderson, Marie Murray CORREO DE NOCHE 18 DE JUNY Nacionalitat i any de producció: Gran Bretanya, 1936 Títol original: Night Mail ALARMA EN EL EXPRESO (VOSE) Producció: John Grierson Nacionalitat i any de producció: Gran Bretanya, Direcció: Basil Wright i Harry Watt 1938 Guió: John Grierson, Basil Wright i Harry Watt Títol original: The Lady Vanishes Fotografia: Henry Fowle i Johan Jones Producció: Edward Black Muntatge: Benjamín Britten Direcció: Alfred Hitchcock Guió: Sydney Gilliatt i Frank Launder LLEGADA DEL TREN Fotografia: Jack Cox Intèrprets: Margaret Lockwood, Michael Nacionalitat i any de producció: França, 1895 Redgrave, Paul Lukas, Dame May Títol original: L'arrivée du train en gare de la Ciotat Direcció: Louis Lumière EL TREN A MALLORCA Pel·lícules de Josep Truyol i A. Barret. Les pel·lícules del mes de juliol i les lU hores I les SU hores tide einem i jazz lizle cinema i tren (imb ¡a cal ¡aburada áe SFM i lonseliería 2 DE JULIOL ÍBbres Públiques. -

Film Essay for "Ride the High Country"

Ride the High Country By Stephen Prince “Ride the High Country” is the eye of the hurricane, the stillness at the center of the storm of transgression that Sam Peckinpah brought to American film in the late 1960s. That it hails from the on- set of that decade and of Peckinpah’s career as a feature film director ac- counts for its singular grace and affabil- ity. The serenity of its outlook and the surety of its convictions about the nature of right and wrong place it far outside the tortured worlds inscribed by his sub- sequent films. At the same time, it shows clearly the thematic obsessions and stylistic hallmarks that he would make his own when American society began to come apart in ways that ena- bled him to become the great poet of Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott as aging hired guns. Courtesy Library late sixties apocalypse. of Congress Collection. Its purity of heart is clean and strong and makes it a on to break with. film that is easy to love, in a way that “The Wild Bunch” and “Straw Dogs” made defiantly difficult for The script’s original title was “Guns in the Afternoon,” viewers. Indeed, its unabashed celebration of and the film carried this title in overseas release. It straight-forward heroism strikes notes that Peckinpah aptly conveys the elegiac tone that Peckinpah never again sounded in his work. This makes it at brought out so strongly using McCrea and Scott as once an outlier among his films and a touchstone of aging Westerners who had become anachronisms in virtues that his subsequent protagonists strive to find a country now largely settled and on the cusp of mo- and to hold and never quite succeed in doing. -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

Case Study: Fritz Lang and Scarlet Street*

Studia Filmoznawcze 31 Wroc³aw 2010 Barry Keith Grant Brock University (Canada) CASE STUDY: FRITZ LANG AND SCARLET STREET* Fritz Lang’s work in film spans the silent era almost from its beginnings through the golden era of German Expressionism in the 1920s and the classic studio sys- tem in Hollywood to the rise of the international co-production. In the course of his career Lang directed more acknowledged classics of the German silent cinema than any other director, made the first important German sound film (M, 1932), and dir ected some of the most important crime films and film noirs of the American studio era, including You Only Live Once (1937), The Big Heat (1953), and Scarlet Street (1945). Critics have commonly divided Lang’s extensive filmography into two major periods, the silent German films and the American studio movies. In the former he had considerable artistic freedom, while in Hollywood he worked against the greater constraints of the studio system and B-picture budgets; yet the thematic and stylistic consistency in Lang’s work across decades, countries, and different production contexts is truly remarkable. Consistently Lang’s films depict an entrapping, claustrophobic, deterministic world in which the characters are controlled by larger forces and internal desires beyond their understanding. In this cruelly indifferent world, people struggle vainly against fate and their own repressed inclinations toward violence. As in Hitchcock’s films, Lang’s often deal with the violent potential lurking within the respectable citizen and suggest that social order requires controlling the beast within. M (1932), Lang’s first sound film, is about a serial child killer (Peter Lorre) who explains to the kangaroo court of criminals about to execute him that he is possessed by a murder- * The text is taken, with the agreement of its author, from his book Film Genre: From Iconog- raphy to Ideology, London 2007, pp.