MASCULINITY AS SPECTACLE REFLECTIONS on MEN and MAINSTREAM CINEMA by STEVE NEALE Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Noir Timeline Compiled from Data from the Internet Movie Database—412 Films

Film Noir Timeline Compiled from data from The Internet Movie Database—412 films. 1927 Underworld 1944 Double Indemnity 1928 Racket, The 1944 Guest in the House 1929 Thunderbolt 1945 Leave Her to Heaven 1931 City Streets 1945 Scarlet Street 1932 Beast of the City, The 1945 Spellbound 1932 I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang 1945 Strange Affair of Uncle Harry, The 1934 Midnight 1945 Strange Illusion 1935 Scoundrel, The 1945 Lost Weekend, The 1935 Bordertown 1945 Woman in the Window, The 1935 Glass Key, The 1945 Mildred Pierce 1936 Fury 1945 My Name Is Julia Ross 1937 You Only Live Once 1945 Lady on a Train 1940 Letter, The 1945 Woman in the Window, The 1940 Stranger on the Third Floor 1945 Conflict 1940 City for Conquest 1945 Cornered 1940 City of Chance 1945 Danger Signal 1940 Girl in 313 1945 Detour 1941 Shanghai Gesture, The 1945 Bewitched 1941 Suspicion 1945 Escape in the Fog 1941 Maltese Falcon, The 1945 Fallen Angel 1941 Out of the Fog 1945 Apology for Murder 1941 High Sierra 1945 House on 92nd Street, The 1941 Among the Living 1945 Johnny Angel 1941 I Wake Up Screaming 1946 Shadow of a Woman 1942 Sealed Lips 1946 Shock 1942 Street of Chance 1946 So Dark the Night 1942 This Gun for Hire 1946 Somewhere in the Night 1942 Fingers at the Window 1946 Locket, The 1942 Glass Key, The 1946 Strange Love of Martha Ivers, The 1942 Grand Central Murder 1946 Strange Triangle 1942 Johnny Eager 1946 Stranger, The 1942 Journey Into Fear 1946 Suspense 1943 Shadow of a Doubt 1946 Tomorrow Is Forever 1943 Fallen Sparrow, The 1946 Undercurrent 1944 When -

El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses

9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 75 Chapter 2 The Passion of El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses I started with the final scene. This lifeless knight who is strapped into the saddle of his horse ...it’s an inspirational scene. The film flowed from this source. —Anthony Mann, “Conversation with Anthony Man,” Framework 15/16/27 (Summer 1981), 191 In order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must take flight into the misty realm of religion. —Karl Marx, Capital, 165 It is precisely visions of the frenzy of destruction, in which all earthly things col- lapse into a heap of ruins, which reveal the limit set upon allegorical contempla- tion, rather than its ideal quality. The bleak confusion of Golgotha, which can be recognized as the schema underlying the engravings and descriptions of the [Baroque] period, is not just a symbol of the desolation of human existence. In it transitoriness is not signified or allegorically represented, so much as, in its own significance, displayed as allegory. As the allegory of resurrection. —Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, 232 The allegorical form appears purely mechanical, an abstraction whose original meaning is even more devoid of substance than its “phantom proxy” the allegor- ical representative; it is an immaterial shape that represents a sheer phantom devoid of shape and substance. —Paul de Man, Blindness and Insight, 191–92 Destiny Rides Again The medieval film epic El Cid is widely regarded as a liberal film about the Cold War, in favor of détente, and in support of civil rights and racial 9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 76 76 Medieval and Early Modern Film and Media equality in the United States.2 This reading of the film depends on binary oppositions between good and bad Arabs, and good and bad kings, with El Cid as a bourgeois male subject who puts common good above duty. -

The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in Postwar American Literature and Film by Sean D

A Shadow Underneath: The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in Postwar American Literature and Film Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Cobb, Sean Daren Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 06:20:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195525 1 A Shadow Underneath: The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in Postwar American Literature and Film by Sean D. Cobb _____________________ Copyright © Sean D. Cobb 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the English Department In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Sean D. Cobb entitled A Shadow Underneath: The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in American Postwar Literature and Film and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of PhD _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/30/07 Prof. Susan White _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/30/07 Prof. Charles Bertsch _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/30/07 Prof. Carlos Gallego Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 Pm Page 3

Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 2 Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 3 Film Soleil D.K. Holm www.pocketessentials.com This edition published in Great Britain 2005 by Pocket Essentials P.O.Box 394, Harpenden, Herts, AL5 1XJ, UK Distributed in the USA by Trafalgar Square Publishing P.O.Box 257, Howe Hill Road, North Pomfret, Vermont 05053 © D.K.Holm 2005 The right of D.K.Holm to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may beliable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The book is sold subject tothe condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in anyform, binding or cover other than in which it is published, and without similar condi-tions, including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publication. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 1–904048–50–1 2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1 Book typeset by Avocet Typeset, Chilton, Aylesbury, Bucks Printed and bound by Cox & Wyman, Reading, Berkshire Film Soleil 28/9/05 3:35 pm Page 5 Acknowledgements There is nothing -

Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema

PERFORMING ARTS • FILM HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF Historical Dictionaries of Literature and the Arts, No. 26 VARNER When early filmgoers watched The Great Train Robbery in 1903, many shrieked in terror at the very last clip, when one of the outlaws turned toward the camera and seemingly fired a gun directly at the audience. The puff of WESTERNS smoke was sudden and hand-colored, and it looked real. Today we can look back at that primitive movie and see all the elements of what would evolve HISTORICAL into the Western genre. Perhaps the Western’s early origins—The Great Train DICTIONARY OF Robbery was the first narrative, commercial movie—or its formulaic yet enter- WESTERNS in Cinema taining structure has made the genre so popular. And with the recent success of films like 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, the Western appears to be in no danger of disappearing. The story of the Western is told in this Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Cinema through a chronology, a bibliography, an introductory essay, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries on cinematographers; com- posers; producers; films like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Dances with Wolves, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, High Noon, The Magnificent Seven, The Searchers, Tombstone, and Unforgiven; actors such as Gene Autry, in Cinema Cinema Kirk Douglas, Clint Eastwood, Henry Fonda, Jimmy Stewart, and John Wayne; and directors like John Ford and Sergio Leone. PAUL VARNER is professor of English at Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas. -

Feature Films

Libraries FEATURE FILMS The Media and Reserve Library, located in the lower level of the west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 0.5mm DVD-8746 2012 DVD-4759 10 Things I Hate About You DVD-0812 21 Grams DVD-8358 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse DVD-0048 21 Up South Africa DVD-3691 10th Victim DVD-5591 24 Hour Party People DVD-8359 12 DVD-1200 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs 12 and Holding DVD-5110 25th Hour DVD-2291 12 Angry Men DVD-0850 25th Hour c.2 DVD-2291 c.2 12 Monkeys DVD-8358 25th Hour c.3 DVD-2291 c.3 DVD-3375 27 Dresses DVD-8204 12 Years a Slave DVD-7691 28 Days Later DVD-4333 13 Going on 30 DVD-8704 28 Days Later c.2 DVD-4333 c.2 1776 DVD-0397 28 Days Later c.3 DVD-4333 c.3 1900 DVD-4443 28 Weeks Later c.2 DVD-4805 c.2 1984 (Hurt) DVD-6795 3 Days of the Condor DVD-8360 DVD-4640 3 Women DVD-4850 1984 (O'Brien) DVD-6971 3 Worlds of Gulliver DVD-4239 2 Autumns, 3 Summers DVD-7930 3:10 to Yuma DVD-4340 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her DVD-6091 30 Days of Night DVD-4812 20 Million Miles to Earth DVD-3608 300 DVD-9078 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea DVD-8356 DVD-6064 2001: A Space Odyssey DVD-8357 300: Rise of the Empire DVD-9092 DVD-0260 35 Shots of Rum DVD-4729 2010: The Year We Make Contact DVD-3418 36th Chamber of Shaolin DVD-9181 1/25/2018 39 Steps DVD-0337 About Last Night DVD-0928 39 Steps c.2 DVD-0337 c.2 Abraham (Bible Collection) DVD-0602 4 Films by Virgil Wildrich DVD-8361 Absence of Malice DVD-8243 -

Anthony Mann, Geoffrey Shurlock, and the Cult of Theosophy John Wranovics

UNCOMMON GROUND ANTHONY MANN, GEOFFREY SHURLOCK, AND THE CULT OF THEOSOPHY John Wranovics hroughout his career, Anthony Mann pushed the envelope regarding what could be shown on Caldwell’s God’s Little Acre (1958), stories that for years had been stalled by censors and branded as unfilmable. screen. With unprecedented acts of violence, such as Raymond Burr throwing molten Cherries As he moved from Poverty Row to major studios, Mann routinely battled the Production Code Administration (PCA), the Jubilee in Chili Williams’ face in Raw Deal (1948), George Murphy slashed to pieces by a motor- industry’s self-policing censorship office, headed by Irish-Catholic Joseph I. Breen. From its inception in 1932 until 1954, ized harrow in Border Incident (1949), or Alex Nicol firing a bullet through Jimmy Stewart’s hand in Geoffrey Manwaring Shurlock served as Breen’s right-hand man. Shurlock even ran the PCA during Breen’s brief stint as general The Man from Laramie (1955), Mann constantly tested the limits. He didn’t shy away from contro- manager of RKO from 1941-1942. He formally took the reins when Breen retired in ’54, serving as America’s chief film censor T versial sexual subjects either, filming adaptations of James M. Cain’s Serenade (1956) and Erskine until his own retirement in January 1968, when introduction of the ratings system made the PCA superfluous. 26 NOIR CITY I NUMBER 21 I filmnoirfoundation.org filmnoirfoundation.org I NUMBER 21 I NOIR CITY 27 In 1900, Katherine Tingley founded the International Theosophical Headquarters, aka “Lomaland,” in Point Loma, a seaside community in San Diego, California “The code is a set of self-regulations based on sound morals pool, England. -

MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES and CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release May 1994 MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS June 24 - September 30, 1994 A retrospective celebrating the seventieth anniversary of Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer, the legendary Hollywood studio that defined screen glamour and elegance for the world, opens at The Museum of Modern Art on June 24, 1994. MGM 70 YEARS: REDISCOVERIES AND CLASSICS comprises 112 feature films produced by MGM from the 1920s to the present, including musicals, thrillers, comedies, and melodramas. On view through September 30, the exhibition highlights a number of classics, as well as lesser-known films by directors who deserve wider recognition. MGM's films are distinguished by a high artistic level, with a consistent polish and technical virtuosity unseen anywhere, and by a roster of the most famous stars in the world -- Joan Crawford, Clark Gable, Judy Garland, Greta Garbo, and Spencer Tracy. MGM also had under contract some of Hollywood's most talented directors, including Clarence Brown, George Cukor, Vincente Minnelli, and King Vidor, as well as outstanding cinematographers, production designers, costume designers, and editors. Exhibition highlights include Erich von Stroheim's Greed (1925), Victor Fleming's Gone Hith the Hind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939), Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and Ridley Scott's Thelma & Louise (1991). Less familiar titles are Monta Bell's Pretty Ladies and Lights of Old Broadway (both 1925), Rex Ingram's The Garden of Allah (1927) and The Prisoner - more - 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 of Zenda (1929), Fred Zinnemann's Eyes in the Night (1942) and Act of Violence (1949), and Anthony Mann's Border Incident (1949) and The Naked Spur (1953). -

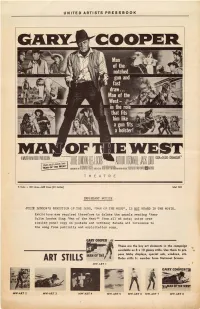

Gary Cooper in 'Man of the West,'

UNITED ARTISTS PRESS BOOK man of the WEST London ArthurO'ConnellLord - Jack SCREENPlAY BY DIRECTED BY Anthony mann AN ASHTON picture - released thru United Artists THEATRE 5 Cols. x 120 Lines - 600 Lines (43 Inches) Mat 503 IMPORTANT NOTICE JULIE LONDON'S RENDITION OF THE SONG, "MAN OF THE WEST", IS not HEARD IN THE MOVIE. exhibitors are required therefore to delete the panels reading "Hear Julie London Sing 'Man of the West'" from all ad mats; snipe over similar panel copy on posters and lobbies; delete all reference to the song from publicity and exploitation copy. These are the key art elements in the campaign available as 8 x 10 glossy stills. Use them to pre- pare lobby displays, special ads, windows, etc. ART STILLS Order stills number from National Screen. MW-ART 1 • 0 • • • MW-ART 2 MW-ART 3 MW-ART 4 MW-ART 5 MW-ART 6 MW-ART 7 MW-ART 8 U1 _• Campaign Catc/,line Sets Surefire Stunt! --------------------------1 I -~ OFFER PRIZES AND CINDERELLA "BOOT"! :I I TICKETS TO THOSE WHO Adapt the popular Cinderella search by look- WIN MOYIE TICKETS! I ing for a boy under 16 years of age who can If the number of this "gun" GET GIVEAWAY GUNS ' 'fits' the holster number on dis THAT "FIT" HOLSTER I fill the boots of "the man of the west." Get an play in our lobby ... you will re extra large western boot and cut it in cross ceive 2 guest admissions to see Latch on to the terrific penetration of the Gary Cooper descriptive in ads and posters: "the role section; then mount it. -

Proquest Dissertations

"The Cross-Heart People": Indigenous narratives,cinema, and the Western Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hearne, Joanna Megan Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 17:56:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290072 •THE CROSS-HEART PEOPLE": INDIGENOLJS NARRATIVES, CINEMA, AND THE WESTERN By Joanna Megan Heame Copyright © Joanna Megan Heame 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3132226 Copyright 2004 by Hearne, Joanna Megan All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3132226 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance 1962, Donovan’S Reef 1963, and Cheyenne Autumn 1964

March 12, 2002 (V:8) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson JOHN FORD (Sean Aloysius O’Fearna, 1 February 1894, Cape Elizabeth, Maine – 31 August 1973, Palm Desert, California, cancer) directed 146 films, 54 of them westerns. He won four Academy Awards for Best Director (*), two more for best documentary (#), five new York Film Critics Best Director awards (+), the Directors’ Guild of America Life Achievement Award (1954), and the first American Film Institute Life Achievement Award (1973). Some of his films are: The Informer*+ 1935, The Prisoner of Shark Island 1936, Stagecoach 1939+, Drums Along the Mohawk 1939, The Long Voyage Home +1940, The Grapes of Wrath* + 1940, Tobacco Road 1941, How Green Was My Valley+ 1941,* The Battle of Midway # 1942 (which he also photographed and edited), December 7th # 1943, They Were Expendable 1945, My Darling Clementine 1946, Fort Apache 1948, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon 1949, Rio Grande 1950, What Price Glory? 1952, The Quiet Man* 1952, Mogambo 1953, Mister Roberts 1955, The Searchers 1956, The Rising of the Moon 1957, The Last Hurrah 1958, Sergeant Rutledge 1960, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance 1962, Donovan’s Reef 1963, and Cheyenne Autumn 1964. His older brother Francis started in movies in 1907 and changed his name to Ford. Jack joined him in Hollywood in 1914, acted in a dozen serials T HE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY and features, and began directing in 1917. He did three films in 1939, all of them classics: Drums VALANCE (1962)123 minutes Along the Mohawk (starring Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert), Young Mr. -

Two Concepts of Liberty Valance: John Ford, Isaiah Berlin, and Tragic Choice on the Frontier, 37 Creighton L

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2004 Two Concepts of Liberty Valance: John Ford, Isaiah Berlin, and Tragic Choice on the Frontier, 37 Creighton L. Rev. 471 (2004) Timothy P. O'Neill The John Marshall Law School, Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Timothy P. O'Neill, Two Concepts of Liberty Valance: John Ford, Isaiah Berlin, and Tragic Choice on the Frontier, 37 Creighton L. Rev. 471 (2004). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/124 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO CONCEPTS OF LIBERTY VALANCE: JOHN FORD, ISAIAH BERLIN, AND TRAGIC CHOICE ON THE FRONTIER TIMOTHY P. O'NEILLt "If as I believe, the ends of men are many, and not all of them are in principle compatible with each other, then the possibil- ity of conflict - and of tragedy - can never wholly be elimi- nated from human life, either personal or social. The necessity of choosing between absolute claims is then an ines- capable characteristicof the human condition." - Isaiah Berlin, "Two Concepts of Liberty" in Isaiah Berlin: The Proper Study of Mankind "We are doomed to choose, and every choice may entail an ir- reparableloss." - Isaiah Berlin, "The Pursuit of the Ideal" in The Crooked Timber of Humanity "Nothing's too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance." - Railroad Conductor to Senator Ransom Stoddard in John Ford's The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance INTRODUCTION 1962 was a good year for movies.