Borders in Post 9/11 Cinema a Dissertation Presented to the Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

Film Noir Timeline Compiled from Data from the Internet Movie Database—412 Films

Film Noir Timeline Compiled from data from The Internet Movie Database—412 films. 1927 Underworld 1944 Double Indemnity 1928 Racket, The 1944 Guest in the House 1929 Thunderbolt 1945 Leave Her to Heaven 1931 City Streets 1945 Scarlet Street 1932 Beast of the City, The 1945 Spellbound 1932 I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang 1945 Strange Affair of Uncle Harry, The 1934 Midnight 1945 Strange Illusion 1935 Scoundrel, The 1945 Lost Weekend, The 1935 Bordertown 1945 Woman in the Window, The 1935 Glass Key, The 1945 Mildred Pierce 1936 Fury 1945 My Name Is Julia Ross 1937 You Only Live Once 1945 Lady on a Train 1940 Letter, The 1945 Woman in the Window, The 1940 Stranger on the Third Floor 1945 Conflict 1940 City for Conquest 1945 Cornered 1940 City of Chance 1945 Danger Signal 1940 Girl in 313 1945 Detour 1941 Shanghai Gesture, The 1945 Bewitched 1941 Suspicion 1945 Escape in the Fog 1941 Maltese Falcon, The 1945 Fallen Angel 1941 Out of the Fog 1945 Apology for Murder 1941 High Sierra 1945 House on 92nd Street, The 1941 Among the Living 1945 Johnny Angel 1941 I Wake Up Screaming 1946 Shadow of a Woman 1942 Sealed Lips 1946 Shock 1942 Street of Chance 1946 So Dark the Night 1942 This Gun for Hire 1946 Somewhere in the Night 1942 Fingers at the Window 1946 Locket, The 1942 Glass Key, The 1946 Strange Love of Martha Ivers, The 1942 Grand Central Murder 1946 Strange Triangle 1942 Johnny Eager 1946 Stranger, The 1942 Journey Into Fear 1946 Suspense 1943 Shadow of a Doubt 1946 Tomorrow Is Forever 1943 Fallen Sparrow, The 1946 Undercurrent 1944 When -

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 Paul L. Robertson Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Appalachian Studies Commons, Literature in English, North America Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons © Paul L. Robertson Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/5854 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robertson i © Paul L. Robertson 2019 All Rights Reserved. Robertson ii The Mountains at the End of the World: Subcultural Appropriations of Appalachia and the Hillbilly Image, 1990-2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. By Paul Lester Robertson Bachelor of Arts in English, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2000 Master of Arts in Appalachian Studies, Appalachian State University, 2004 Master of Arts in English, Appalachian State University, 2010 Director: David Golumbia Associate Professor, Department of English Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2019 Robertson iii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank his loving wife A. Simms Toomey for her unwavering support, patience, and wisdom throughout this process. I would also like to thank the members of my committee: Dr. David Golumbia, Dr. -

MASCULINITY AS SPECTACLE REFLECTIONS on MEN and MAINSTREAM CINEMA by STEVE NEALE Downloaded From

MASCULINITY AS SPECTACLE REFLECTIONS ON MEN AND MAINSTREAM CINEMA BY STEVE NEALE Downloaded from http://screen.oxfordjournals.org/ OVER THE PAST ten years or so, numerous books and articles 1 Laura Mulvey, have appeared discussing the images of women produced and circulated 'Visual Pleasure by the cinematic institution. Motivated politically by the development and Narrative Cinema', Screen of the Women's Movement, and concerned therefore with the political Autumn 1975, vol and ideological implications of the representations of women offered by at Illinois University on July 18, 2014 16 no 3, pp 6-18. the cinema, a number of these books and articles have taken as their basis Laura Mulvey's 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema', first published in Screen in 1975'. Mulvey's article was highly influential in its linking together of psychoanalytic perspectives on the cinema with a feminist perspective on the ways in which images of women figure within main- stream film. She sought to demonstrate the extent to which the psychic mechanisms cinema has basically involved are profoundly patriarchal, and the extent to which the images of women mainstream film has produced lie at the heart of those mechanisms. Inasmuch as there has been discussion of gender, sexuality, represen- tation and the cinema over the past decade then, that discussion has tended overwhelmingly to centre on the representation of women, and to derive many of its basic tenets from Mulvey^'s article. Only within the Gay Movement have there appeared specific discussions of the represen- tation of men. Most of these, as far as I am aware, have centred on the representations and stereotypes of gay men. -

El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses

9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 75 Chapter 2 The Passion of El Cid and the Circumfixion of Cinematic History: Stereotypology/ Phantomimesis/ Cryptomorphoses I started with the final scene. This lifeless knight who is strapped into the saddle of his horse ...it’s an inspirational scene. The film flowed from this source. —Anthony Mann, “Conversation with Anthony Man,” Framework 15/16/27 (Summer 1981), 191 In order, therefore, to find an analogy, we must take flight into the misty realm of religion. —Karl Marx, Capital, 165 It is precisely visions of the frenzy of destruction, in which all earthly things col- lapse into a heap of ruins, which reveal the limit set upon allegorical contempla- tion, rather than its ideal quality. The bleak confusion of Golgotha, which can be recognized as the schema underlying the engravings and descriptions of the [Baroque] period, is not just a symbol of the desolation of human existence. In it transitoriness is not signified or allegorically represented, so much as, in its own significance, displayed as allegory. As the allegory of resurrection. —Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, 232 The allegorical form appears purely mechanical, an abstraction whose original meaning is even more devoid of substance than its “phantom proxy” the allegor- ical representative; it is an immaterial shape that represents a sheer phantom devoid of shape and substance. —Paul de Man, Blindness and Insight, 191–92 Destiny Rides Again The medieval film epic El Cid is widely regarded as a liberal film about the Cold War, in favor of détente, and in support of civil rights and racial 9780230601253ts04.qxd 03/11/2010 08:03 AM Page 76 76 Medieval and Early Modern Film and Media equality in the United States.2 This reading of the film depends on binary oppositions between good and bad Arabs, and good and bad kings, with El Cid as a bourgeois male subject who puts common good above duty. -

The Ideology of the Long Take in the Cinema of Alfonso Cuarón by BRUCE ISAACS

4.3 Reality Effects: The Ideology of the Long Take in the Cinema of Alfonso Cuarón BY BRUCE ISAACS Between 2001 and 2013, Alfonso Cuarón, working in concert with long-time collaborator, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, produced several works that effectively modeled a signature disposition toward film style. After a period of measured success in Hollywood (A Little Princess [1995], Great Expectations [1998]), Cuarón and Lubezki returned to Mexico to produce Y Tu Mamá También (2001), a film designed as a low- budget, independent vehicle (Riley). In 2006, Cuarón directed Children of Men, a high budget studio production, and in March 2014, he won the Academy Award for Best Director for Gravity (2013), a film that garnered the praise of the American and European critical establishment while returning in excess of half a billion dollars worldwide at the box office (Gravity, Box Office Mojo). Lubezki acted as cinematographer on each of the three films.[1] In this chapter, I attempt to trace the evolution of a cinematographic style founded upon the “long take,” the sequence shot of excessive duration. Reality Effects Each of Cuarón’s three films under examination demonstrates a fixation on the capacity of the image to display greater and more complex indices of time and space, holding shots across what would be deemed uncomfortable durations in a more conventional mode of cinema. As Udden argues, Cuarón’s films are increasingly defined by this mark of the long take, “shots with durations well beyond the industry standard” (26-27). Such shots are “attention-grabbing spectacles,” displaying the virtuosity of the filmmaker over and above the requirement of narrative unfolding. -

The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in Postwar American Literature and Film by Sean D

A Shadow Underneath: The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in Postwar American Literature and Film Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Cobb, Sean Daren Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 30/09/2021 06:20:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195525 1 A Shadow Underneath: The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in Postwar American Literature and Film by Sean D. Cobb _____________________ Copyright © Sean D. Cobb 2008 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the English Department In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2008 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Sean D. Cobb entitled A Shadow Underneath: The Secret History of Paranoia, Borders and Terrorism in American Postwar Literature and Film and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of PhD _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/30/07 Prof. Susan White _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/30/07 Prof. Charles Bertsch _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 11/30/07 Prof. Carlos Gallego Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

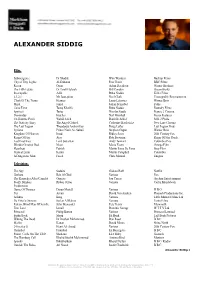

Alexander Siddig

ALEXANDER SIDDIG Film: Submergence Dr Shadid Wim Wenders Backup Films City of Tiny Lights Al-Dabaran Pete Travis BBC Films Recon Omar Adam Davidson Warner Brothers The Fifth Estate Dr Tarek Haliseh Bill Condon DreamWorks Inescapable Adib Ruba Nadda Killer Films 4.3.2.1 Mr Jauo-pinto Noel Clark Unstoppable Entertainment Clash Of The Titans Hermes Louis Leterrier Warner Bros Miral Jamal Julian Schnabel Pathe Cairo Time Tareq Khalifa Ruba Nadda Foundry Films Spy(ies) Tariq Nicolas Saada France 2 Cinema Doomsday Hatcher Neil Marshall Focus Features Un Homme Perdi Wahid Saleh Danielle Arbid M K 2 Prods. The Nativity Story The Angel Gabriel Catherine Hardwicke New Line Cinema The Last Legion Theodorus Andronikos Doug Lefler Last Legion Prod Syriana Prince Nasir Al- Subaii Stephen Gagan Warner Bros Kingdom Of Heaven Imad Ridley Scott 20th Century Fox Reign Of Fire Ajay Rob Bowman Reign Of Fire Prods. Last First Kiss Lord Sebastian Andy Tennant Columbia Pics World's Greatest Dad Nisse Maria Essen Omega Film Heartbeat Patrick Martin Lima De Faria Stop Film Vertical Limit Karim Martin Campbell Columbia A Dangerous Man Faisal Chris Menaul Enigma Television: The Spy Sudaini Gideon Raff Netflix Gotham Ra's Al Ghul Various Fox The Kennedys After Camelot Onassis Jon Cassar Asylum Entertainment Peaky Blinders Ruben Oliver Various Caryn Mandabach Productions Game Of Thrones Doran Martell Various H B O Tut Amun David Von Ancken Pharaoh Productions Inc. Atlantis King Various Little Monster Films Ltd Da Vinci's Demons Saslan Al Rahim Various Tonto Films Falcon; -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

On Anamorphic Adaptations and the Children of Men

ISSN 1751-8229 Volume Eleven, Number Two On Anamorphic Adaptations and the Children of Men Gregory Wolmart, Drexel University, United States Abstract In this article, I expand upon Slavoj Zižek’s “anamorphic” reading of Alfonso Cuarón’s Children of Men (2006). In this reading, Zižek distinguishes between the film’s ostensible narrative structure, the “foreground,” as he calls it, and the “background,” wherein the social and spiritual dissolution endemic to Cuaron’s dystopian England draws the viewer into a recognition of the dire conditions plaguing the post-9/11, post-Iraq invasion, neoliberal world. The foreground plots the conventional trajectory of the main character Theo from ordinary, disaffected man to self-sacrificing hero, one whose martyrdom might pave the way for a new era of regeneration. According to Zižek, in this context the foreground merely entertains, while propagating some well-worn clichés about heroic individualism as demonstrated through Hollywood’s generic conventions of an action- adventure/political thriller/science-fiction film. Zižek contends that these conventions are essential to the revelation of the film’s progressive politics, as “the fate of the individual hero is the prism through which … [one] see[s] the background even more sharply.” Zižek’s framing of Theo merely as a “prism” limits our understanding of the film by not taking into account its status as an adaptation of P.D. James’ The Children of Men (1992). This article offers such an account by interpreting the differences between the film and its literary source as one informed by the transition from Cold War to post-9/11 neoliberal conceptions of identity and politics.