Introduction: After Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: the Man and His Works

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 1977 CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works Susan M. Voss University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Voss, Susan M., "CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works" (1977). Nebraska Anthropologist. 145. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/145 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE NEBRASKA ANTHROPOLOGIST, Volume 3 (1977). Published by the Anthropology Student Group, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 21 / CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works by Susan M. Voss 'INTRODUCTION "Claude Levi-Strauss,I Professor of Social Anth- ropology at the College de France, is, by com mon consent, the most distinguished exponent ~f this particular academic trade to be found . ap.ywhere outside the English speaking world ... " (Leach 1970: 7) With this in mind, I am still wondering how I came to be embroiled in an attempt not only to understand the mul t:ifaceted theorizing of Levi-Strauss myself, but to interpret even a portion of this wide inventory to my colleagues. ' There is much (the maj ori ty, perhaps) of Claude Levi-Strauss which eludes me yet. To quote Edmund Leach again, rtThe outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or in English, is that it is difficul tto unders tand; his sociological theories combine bafflingcoinplexity with overwhelm ing erudi tion"., (Leach 1970: 8) . -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Descent Systems and Ideal Language Rodney Needham Philosophy of Science, Vol

Descent Systems and Ideal Language Rodney Needham Philosophy of Science, Vol. 27, No. 1. (Jan., 1960), pp. 96-101. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-8248%28196001%2927%3A1%3C96%3ADSAIL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-F Philosophy of Science is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Mar 25 07:12:03 2008 DISCUSSION DESCENT SYSTEMS AND IDEAL LANGUAGE* RODNEY NEEDHAM University of Oxford This note is written in response to Gellner's "Ideal Language and Kinship Structure" (l).l In that article he tries to shed some light on the notion of an ideal language by constructing in outline an ideal language for what he calls "kinship structure theory". -

Anthropology and Folklore Studies in India: an Overview

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 Anthropology and Folklore Studies in India: An Overview Kundan Ghosh1, Pinaki Dey Mullick2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Mahishadal Girls‟ College, Rangibasan, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Haldia Government College, Haldia, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India Abstract: Anthropology has a long tradition of folklore studies. Anthropologist studied both the aspect of folklore i.e. life and lore. Folklore became a popular medium in anthropological studies and using emic approach researchers try to find out the inner meaning of different aspects of culture. This paper focused on the major approaches of the study of Anthropology and Folklore. It is an attempt to classify different phases of Anthropology of Folklore studies in India and understand the historical development of Anthropology of Folklore studies in India. It is observed that, both theoretical and methodological approaches were changed with the time and new branches are emerged with different dimensions. Keywords: Folklore, emic approach, lore, Anthropology of Folklore, culture. 1. Introduction closure term „folklore‟. Folklore includes both verbal and non-verbal forms. Oral literature, however, is usually Of the four branches of Anthropology, Cultural includes verbal folklore only and does not include games Anthropology is most closely associated with folklore and dances. Different cultures have different categories of (Bascom, 1953). The term folklore was coined by W. J. folk literature. Dundes is of the opinion that contemporary Thoms in the year 1846 and was used by him in the study of oral literature tends to see folklore as a reflection of magazine entitled The Athenaenum of London. -

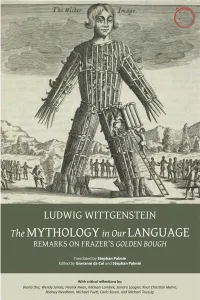

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

Ethnographic Notes on Two Operations of the Body Among a Community of Balinese on Lombok

ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON TWO OPERATIONS OF THE BODY AMONG A COMMUNITY OF BALINESE ON LOMBOK 'It is ... an axiom in anthropology that what is needed is not discursive treatment of large but the minute discussion of special themes.' N. W. Thomas ' ... we really do not know much about what people actually feel.' Rodney Needham I Hocart once wrote (1970: 11) that life depended upon many , and that one the upon which it depended was food; few, surely, would take serious issue with this contention. Yet (as we shall see) there has arisen in the literature about the Balinese an interpretation about an aspect of their life which at first sight does not seem to accord well with the fundamental importance which food has in creating and sustaining life. In Naven, Bateson contended (1936: 115) that 'culture standardises the emotional reactions of individuals, and modi fies the organization of their sentiments.' It is not surprising, therefore, that in his later work about the Balinese in collaboration with Margaret Mead he should have tried to find out how the Balinese, by any standard a remarkable people, organise these aspects of human experience which are 'of such radical and pervasive importance ... r (Needham 1971: lix). Bateson and Mead came to the conclusion in their Balinese 121 122 Andrew Duff-Cooper Character that - among other slightly odd things which the Balinese are supposed to be doing when, for instance, they chew betel, or when they respond to children in different ways - when the Balinese eat they are doing something akin to defecation, for 'the Balinese cultural emphases .•. -

INTRODUCTION Drawn from Life: Mary Douglas's Personal Method

INTRODUCTION Drawn from life: Mary Douglas’s personal method Richard Fardon Mary Douglas (1921–2007) was the most widely read British anthropolo- gist of the second half of the twentieth century. Her writings continue to inspire researchers in numerous fields in the twenty-first century.1 This vol- ume of papers, first published over a period of almost fifty years, provides insights into the wellsprings of her style of thought and manner of writing. More popular counterparts to many of Douglas’s academic works – either the first formulation of an argument, or its more general statement – were often published around the same time as a specialist version. These first thoughts and popular re-imaginings are particularly revealing of the close relation between Douglas’s intellectual and personal concerns, a convergence that became more overt in her late career, when Mary Douglas occasionally wrote autobiographi- cally, explaining her ideas in relation to her upbringing, her family, and her experiences as both a committed Roman Catholic and a social anthropologist in the academy. The four social types of her theoretical writings – hierarchy, competition, the enclaved sect, and individuals in isolation – extend to remote times and distant places, prototypes that literally were close to home for her. This ability to expand and contract a restricted range of formal images allowed Mary Douglas to enter new fields of study with startling rapidity, to link unlikely domains of thought (through analogy, most frequently with religion), and to accommodate the most diverse examples in comparative frameworks. It was the way, to put it baldly, she made things fall into place. -

The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Mur- Doch

University of Szeged Faculty of Arts Doctoral Dissertation The German Exile Literature and the Early Novels of Iris Mur- doch Dávid Sándor Szőke Supervisors: Dr. Zoltán Kelemen Dr. Anna Kérchy 2021 Acknowledgements I have a great number of people to thank for their support throughout this thesis, whether this support has been academic, financial, or spiritual. First of all, I would like to thank my supervisors, Dr Zoltán Kelemen and Dr Anna Kérchy for their unending help, encouragement and faith in me during my research. Their knowledge about the Holocaust, 20th century English woman writers and minorities has given exceptional depth to my understanding of Murdoch, Steiner, Canetti and Adler. The eye-opening essays and lectures by Dr Peter Weber about the Romanian painter and Holocaust survivor Arnold Daghani’s time in England provided a genesis for this thesis. Had it not for him, I would not have thought about putting Murdoch’s thinking in the context of Cen- tral European refugee literature and culture during and after the Second World War. This thesis owes much to the 2017 Holocaust Conference in Szeged (19 October) and the 2019 International Holocaust Conference in Halle (14-16 November). I would like to express my gratitude to the March of the Living Hungary, the Holocaust Memorial Centre Budapest, the Memory Point of Hódmezővásárhely, the synagogues of Szeged and Hódmezővásárhely, Professor Werner Nell (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), Professor Thomas Bremer (Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg), Professor Sue Vice (University of Shef- field), and Dr Zoltán Kelemen for making these events possible. During my PhD, as part of the Erasmus ++ programme I spent an entire year at Martin- Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, where I made a great deal of research about the German coming to terms with the past. -

Practical Cosmologies Götz Hoeppe

Document generated on 09/25/2021 4:58 p.m. Ethnologies Practical Cosmologies Götz Hoeppe Devenirs de l’ethnologie Article abstract Whither Ethnology? th For much of the 20 century, indigenous cosmologies, understood as the Volume 40, Number 2, 2018 totalizing worldviews of delimited social groups, were one of ethnology’s central topics. In the last few decades, however, the concept of cosmology no URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1056384ar longer sat well with many ethnologists’ wariness of identifying social wholes as DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1056384ar analytic units and with accepting correspondences of social organization with orders of time, space, and color, among others. Recently, Allen Abramson and Martin Holbraad, in their 2014 book Framing Cosmologies, called for a “second See table of contents wind” of anthropologists’ attention to cosmologies, now including popular understandings of Western science. While endorsing this broadened attention to cosmology and the uses of analyst’s perspectives, I call for remaining Publisher(s) attentive to the practical uses of cosmologies by the actors that ethnographers learn from. This entails attending to the social accountabilities and Association Canadienne d’Ethnologie et de Folklore organizational contexts that constrain how people act. I seek to illustrate this by drawing on ethnographies of fishers in south India as well as of ISSN astrophysicists in Germany. 1481-5974 (print) 1708-0401 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Hoeppe, G. (2018). Practical Cosmologies. Ethnologies, 40(2), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.7202/1056384ar Tous droits réservés © Ethnologies, Université Laval, 2019 This document is protected by copyright law. -

ED166111.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME lip166 f1i SO 011 492 AUTHOR Hanna, Judith Lynne TITLE The Anthropology of Dance. A Selected Bipliography. PUB DATE 78 NOTE 19p.; Revised edition DRS PRICE MF-$0.83, HC-$1.67 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Anthropology; *Bibliographies; Body Language; Communication. (Thought Transfer); Creativity; *Dance; Fine Arts; Motion; Music; Symbolism ABSTRACT ll Overt 250 monographs, journal articles, and papers are cited in this selected bibliography of resources on the anthropology of dance. Most of the entries were published during the 1960s and 1970s. 'Entries are arranged alphabetically by author and give information on title, publisher or journal, date, and page numbers. The bibliography is presented in ten major sections. Section one, 'General Theory relevant to the Study of Dance, contains subcategories of communication and semiotics, symbolism and ritual, aesthetics, creativity and cognition,- perception, and emotion. Section two on methods contains subcategories of movement notation-and analytic units, and structural analyses of dance. Sections three through nine present citations on the following topics: conceptualizations of dance, reviews of dance study, aesthetics in dance, dance--group dynamics and change, politics and dance, transcendance and dance, and symbolism. Section ten on interrelationships of the arts explores music, 'art, costume, and body decoration. The bikliography is not seant to be comprehensive or to include items of uniform gdality. The material presented reflects the author's view of what dance researchers should be familiar with and what the field of the- anthropology of dance should encompass. (AV) *************************************Ii**********pc**4;*****************. * Reproductions supplied by EDES are the best that can be made from the original document. -

World Hau Books

WORLD Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WORLD AN ANthrOPOLOgical EXAMINatION João de Pina-Cabral The Malinowski Monographs Series Hau Books Chicago © 2017 Hau Books and João de Pina-Cabral The Malinowski Monographs Series (Volume 1) The Malinowski Monographs showcase groundbreaking monographs that contribute to the emergence of new ethnographically-inspired theories. In tribute to the foundational, yet productively contentious, nature of the ethnographic imagination in anthropology, this series honors Bronislaw Malinowski, the coiner of the term “ethnographic theory.” The series publishes short monographs that develop and critique key concepts in ethnographic theory (e.g., money, magic, belief, imagination, world, humor, love, etc.), and standard anthropological monographs—based on original research—that emphasize the analytical move from ethnography to theory. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-24-3 LCCN: 2016961546 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi chapter one World 1 chapter two Transcendence 31 -

William Collins Donahue

William Collins Donahue 816 North St. Peter Street ● South Bend, IN 46617 Email: [email protected] Cell: 919.428.5829 Department of German & Russian Languages & Literatures University of Notre Dame ● 318 O’Shaughnessy Hall Notre Dame, IN 46556 ● 574.631.5572 Current Appointments University of Notre Dame: Director, Nanovic Institute for European Studies John J. Cavanaugh, C.S.C., Professor of the Humanities Professor of German Concurrent Professor of Film, Television, and Theatre Duke University Adjunct Professor of German Studies and Member of the Duke Graduate School Faculty (2015 – present) University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill: Member, Graduate School Faculty (2011 – present) Employment History University of Notre Dame: Chair, Department of German & Russian, July, 2015 – December, 2018 Fellow of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, 2015-18 Duke University Bishop-MacDermott Family Professor of Germanic Languages & Literature (2013-15) Member, Bass Society of Fellows (2013-15) Chair, Department of Germanic Languages and Literature (2008 – 2014) Professor, Germanic Languages & Literature (2011-15) Professor, The Program in Literature (2011-15) Member of the Faculty of Jewish Studies (2006-15) and the Jewish Studies Executive Committee (2006—2014) Academic Director, Duke in Berlin (semester, year, and engineering programs; 2006- 15). Advising, Curriculum and Instructional Review, Program design, Personnel Review, Assessment. Duke Today story about Duke in Berlin press coverage in Berlin’s Der Tagesspiegel: http://today.duke.edu/2012/10/germancoverage Director and Founder, Duke-Rutgers Summer in Berlin (2006-15). Six week summer program. University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill: Member, Graduate School Faculty (2011 – present) Adjunct Professor of German Studies (2011-15) Adjunct Associate Professor of German Studies (2008–11).