Anthropology and Folklore Studies in India: an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: the Man and His Works

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 1977 CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works Susan M. Voss University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Voss, Susan M., "CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works" (1977). Nebraska Anthropologist. 145. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/145 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE NEBRASKA ANTHROPOLOGIST, Volume 3 (1977). Published by the Anthropology Student Group, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 21 / CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works by Susan M. Voss 'INTRODUCTION "Claude Levi-Strauss,I Professor of Social Anth- ropology at the College de France, is, by com mon consent, the most distinguished exponent ~f this particular academic trade to be found . ap.ywhere outside the English speaking world ... " (Leach 1970: 7) With this in mind, I am still wondering how I came to be embroiled in an attempt not only to understand the mul t:ifaceted theorizing of Levi-Strauss myself, but to interpret even a portion of this wide inventory to my colleagues. ' There is much (the maj ori ty, perhaps) of Claude Levi-Strauss which eludes me yet. To quote Edmund Leach again, rtThe outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or in English, is that it is difficul tto unders tand; his sociological theories combine bafflingcoinplexity with overwhelm ing erudi tion"., (Leach 1970: 8) . -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Descent Systems and Ideal Language Rodney Needham Philosophy of Science, Vol

Descent Systems and Ideal Language Rodney Needham Philosophy of Science, Vol. 27, No. 1. (Jan., 1960), pp. 96-101. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-8248%28196001%2927%3A1%3C96%3ADSAIL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-F Philosophy of Science is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Mar 25 07:12:03 2008 DISCUSSION DESCENT SYSTEMS AND IDEAL LANGUAGE* RODNEY NEEDHAM University of Oxford This note is written in response to Gellner's "Ideal Language and Kinship Structure" (l).l In that article he tries to shed some light on the notion of an ideal language by constructing in outline an ideal language for what he calls "kinship structure theory". -

Who Heard the Rhymes, and How: Shakespeare’S Dramaturgical Signals

Oral Tradition, 11/2 (1996): 190-221 Who Heard the Rhymes, and How: Shakespeare’s Dramaturgical Signals Burton Raffel The Audience “The many-headed multitude” was how, in 1601, a contemporary referred to the Shakespearian audience (Salgado 1975:22). “Amazed I stood,” wondered an anonymous versifier in 1609, “to see a crowd/ Of civil throats stretched out so lowd;/ (As at a new play) all the rooms/ Did swarm with gentles mix’d with grooms.”1 This wide-ranging appeal considerably antedated Shakespeare’s plays: though he very significantly shaped its later course, he profited from rather than created the solidly popular status of the Elizabethan and, above all, the London stage, for “London was where the players could perform in their own custom-built playhouses, week after week and year after year. In London there were regular venues, regular audiences, regular incomes.”2 The first playhouses had been built in 1576; at least two professional “playhouses were flourishing in 1577.”3 (Shakespeare was then a country lad of thirteen.) The urgency of clerical denunciations, then as now, provides particularly revealing evidence of the theater’s already well- established place in many Londoners’ hearts.4 1 Idem:29. Festivity was of course a far more important aspect of Elizabethan life. “The popular culture of Elizabethan England . is characterized first and foremost by its general commitment to a world of merriment” (Laroque 1991:33). 2 Gurr 1992:6. And, just as today, those who wielded political power took most seriously the ancillary economic benefits produced by London’s professional theaters. See Harrison 1956:112-14, for the authorities’ immensely positive reaction, when appealed to by the watermen who ferried playgoers back and forth across the Thames, and whose profitable employment was being interfered with. -

15.1 Introduction 15.2 West African Oral and Written Traditions

Name and Date: _________________________ Text: HISTORY ALIVE! The Medieval World 15.1 Introduction Medieval cultures in West Africa were rich and varied. In this chapter, you will explore West Africa’s rich cultural legacy. West African cultures are quite diverse. Many groups of people, each with its own language and ways of life, have lived in the region of West Africa. From poems and stories to music and visual arts, their cultural achievements have left a lasting mark on the world. Much of West African culture has been passed down through its oral traditions. Think for a moment of the oral traditions in your own culture. When you were younger, did you learn nursery rhymes from your family or friends? How about sayings such as “A penny saved is a penny earned”? Did you hear stories about your grandparents or more distant ancestors? You can probably think of many ideas that were passed down orally from one generation to the next. Kente cloth and hand-carved Suppose that your community depends on you to furniture are traditional arts in West remember its oral traditions so they will never be Africa. forgotten. You memorize stories, sayings, and the history of your city or town. You know about the first people who lived there. You know how the community grew, and which teams have won sports championships. On special occasions, you share your knowledge through stories and songs. You are a living library of your community’s history and traditions. In parts of West Africa, there are people whose job it is to preserve oral traditions and history in this way. -

Superstitions & Old Wives Tales

1 Superstitions & Old Wives Tales Selected from the web pages of Corsinet.com http://www.corsinet.com Provided to you free in PDF format by your friends at: The Activity Director’s Office Providing Online Resources for Activity Directors in Long Term Health Care Facilities http://www.theactivitydirectorsoffice.com 2 ACORN An acorn should be carried to bring luck and ensure a long life. An acorn at the window will keep lightning out AMBER Amber beads, worn as a necklace, can protect against illness or cure colds. AMBULANCE Seeing an ambulance is very unlucky unless you pinch your nose or hold your breath until you see a black or a brown dog. Touch your toes Touch your nose Never go in one of those Until you see a dog. APPLE Think of five or six names of boys or girls you might marry, As you twist the stem of an apple, recite the names until the stem comes off. You will marry the person whose name you were saying when the stem fell off. An apple a day Keeps the doctor away. If you cut an apple in half and count how many seeds are inside, you will also know how many children you will have. BABY To predict the sex of a baby: Suspend a wedding band held by a piece of thread over the palm of the pregnant girl. If the ring swings in an oval or circular motion the baby will be a girl. If the ring swings in a straight line the baby will be a boy. -

UNIT 3 INDIAN FOLKLORE: FORMS, Concerns of Indian Folk PATTERNS and VARIATIONS Literature

Thematic and Narrative UNIT 3 INDIAN FOLKLORE: FORMS, Concerns of Indian Folk PATTERNS AND VARIATIONS Literature Structure 3.0 Objectives 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Indian Folklore Forms 3.3 Folk Drama and Theatre 3.4 Community Songs and Dances 3.5 Let Us Sum Up 3.6 References and Further Readings 3.7 Check Your Progress: Possible Questions 3.0 OBJECTIVES After reading this unit, you will be able to • different forms and patterns of Indian folklore; • different forms and variations of folk drama and theatre; and • different forms and variations of folksongs and dances. 3.1 INTRODUCTION Folklore, in modern usage, is an academic discipline, the subject matter of which comprises the sum total of traditionally derived and orally or imitatively transmitted literature, material culture, and customs of subcultures within predominantly literate and technologically advanced societies; comparative study among wholly or mainly non-literate societies belongs to the disciplines of ethnology and anthropology. In popular usage, the term folklore is sometimes restricted to the oral literature tradition. Folklore studies began in the early 19th century. The first folklorists concentrated exclusively upon rural peasants, preferably uneducated, and a few other groups relatively untouched by modern ways of life (e.g. gypsies). Their aim was to trace preserved archaic customs and beliefs to their remote origins in order to trace the mental history of mankind. In Germany, Jacob Grimm used folklore to illuminate Germanic religion of the Dark Ages. In Britain, Sir Edward Taylor, Andrew Lang, and others combined data from anthropology and folklore to “reconstruct” the beliefs and rituals of prehistoric man. -

Rethinking Indian Folklore in a Postcolonial World

K i r i n N a r a y a n University of Wisconsin, Madison Banana Republics and V.I. Degrees: Rethinking Indian Folklore in a Postcolonial World Abstract In the history of scholarship on folklore in India, little attention has been directed towards the relationship between folklore and social change. This paper reviews British-based folklore studies in India, identitying a paradigm of self-contained peasant authenticity that viewed references to changing social realities as adultera tions that must be edited out. It then contrasts such suppressions of change with the conscious revamping of folklore materials to disseminate nationalist, Marxist, feminist, and development ideologies. Next, it turns to contemporary examples of creative change in folklore, with a focus on urban joke cycles that are largely ignored by folklorists. Finally, it ends with suggestions for theoretical reorienta tions breaking down the rigid distinction between “us” as metropolitan analysts, and “ them’,as the folk enmeshed in tradition. Key w ords: India — history of folklore — social change — colonialism — joke cycles — positioned subjects Asian Folklore Studies,Volume 52,1993, 177-204 N their introduction to the landmark volume, Another Harmony: New Essays on the Folklore of India (1986), Stuart B lackburn and I A. K. Ram anujan surveyed the history of folklore studies in India and suggested avenues for future research. Among the promising areas for research they listed was folklore’s relation to social change. They wrote, “If . folklore must be studied in all its forms, we should not neglect the most contemporary. How does it respond to the ur banization, mechanization, and cash economy that are reshaping Indian society (or at least large segments of it?)’,(27). -

16 Ideas for Creating New Holiday Tradition After a Death

16 Ideas for Creating New Holiday Tradition After a Death 1. Food: Holiday dish: Choose your loved one’s favorite dish (or recipe) and make sure the dish is present at your celebration year after year. For example, my family makes “Auntie’s beans”. Why are they “Auntie’s beans”? I have no idea, I’m pretty sure “Auntie’s beans” is the same thing as plain ole green bean casserole! • Favorite dessert: Instead of choosing a dish, choose their favorite dessert to make every year. • Breakfast: If the holiday dinner is crazy, crowded, and hectic, start a tradition of having your loved one’s favorite breakfast foods with just your immediate family. • After dinner drinks: If the person who died wasn’t a part of the family celebration, start a tradition of meeting friends and family in the evening to remember the person who died over hot cocoa and eggnog. • Cookie recipe: This is my personal favorite, use your loved one’s recipe to make Christmas cookies. I used my mother’s recipe this year and shared them on Facebook with my far away family. 2. Music • Holiday playlist: Have a go-to list of holiday songs that remind you of your loved one. • Sing: Start a tradition that involves singing your loved one’s favorite holiday songs. My family always sings Silent Night just before going to bed on Christmas Eve and it always makes me cry. (Here’s a post about when holiday songs become sad) You could also try traditions like these… • Have a caroling party before the holidays where you invite all your family and friends • Have a sing-a-long after holiday dinner 3. -

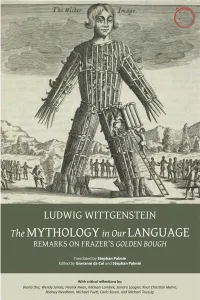

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

Ethnographic Notes on Two Operations of the Body Among a Community of Balinese on Lombok

ETHNOGRAPHIC NOTES ON TWO OPERATIONS OF THE BODY AMONG A COMMUNITY OF BALINESE ON LOMBOK 'It is ... an axiom in anthropology that what is needed is not discursive treatment of large but the minute discussion of special themes.' N. W. Thomas ' ... we really do not know much about what people actually feel.' Rodney Needham I Hocart once wrote (1970: 11) that life depended upon many , and that one the upon which it depended was food; few, surely, would take serious issue with this contention. Yet (as we shall see) there has arisen in the literature about the Balinese an interpretation about an aspect of their life which at first sight does not seem to accord well with the fundamental importance which food has in creating and sustaining life. In Naven, Bateson contended (1936: 115) that 'culture standardises the emotional reactions of individuals, and modi fies the organization of their sentiments.' It is not surprising, therefore, that in his later work about the Balinese in collaboration with Margaret Mead he should have tried to find out how the Balinese, by any standard a remarkable people, organise these aspects of human experience which are 'of such radical and pervasive importance ... r (Needham 1971: lix). Bateson and Mead came to the conclusion in their Balinese 121 122 Andrew Duff-Cooper Character that - among other slightly odd things which the Balinese are supposed to be doing when, for instance, they chew betel, or when they respond to children in different ways - when the Balinese eat they are doing something akin to defecation, for 'the Balinese cultural emphases .•. -

The Perspective from Folklore Studies

Oral Tradition, 18/1 (2003): 116-117 The Perspective from Folklore Studies Pertti Anttonen Coming from the field of folklore studies, I understand by oral tradition the oral transmission and communication of knowledge, conceptions, beliefs, and ideas, and especially the formalization and formulation of these into reports, practices, and representations that foreground elements that favor their replication. The formalized verbal products of oral tradition range from lengthy epic poems, songs, chants, and narratives to proverbs, slogans, and idiomatic phrases, coinciding thus with the conventional categories of folklore. Yet, instead of confining the concept to the genres of folklore only, I would prefer seeing oral tradition as a conceptual entrance point into the observation, study, and theorization of the transmission and argumentation of ideas, beliefs, and practices, including the construction of various political mythologies in the organization and symbolic representation of social groups. As formalized texts, oral tradition calls for the study of poetic patterning, structure, and intertextuality. As performance, oral tradition calls for the study of cognitive conceptualization and modeling, memorization, and variation. As argumentation, oral tradition calls for the study of social function, meaning, identity construction, construction of history and mythology, claims of ownership, and the politics of representation. As tradition, oral tradition calls for the study of transmission, replication and copying, and de- and recontextualization. I find all of these approaches fundamentally important and mutually complementary. If there is a new direction to be taken that would further complement them, I think it should concern the concept of tradition itself, which has tended to be used as an explanation, instead of being that which is explained.