Mary Douglas and Institutions Dean Pierides University of Stirling D.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mary Douglas: Purity and Danger

Purity and Danger This remarkable book, which is written in a very graceful, lucid and polemical style, is a symbolic interpretation of the rules of purity and pollution. Mary Douglas shows that to examine what is considered as unclean in any culture is to take a looking-glass approach to the ordered patterning which that culture strives to establish. Such an approach affords a universal understanding of the rules of purity which applies equally to secular and religious life and equally to primitive and modern societies. MARY DOUGLAS Purity and Danger AN ANALYSIS OF THE CONCEPTS OF POLLUTION AND TABOO LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in 1966 ARK Edition 1984 ARK PAPERBACKS is an imprint of Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001. © 1966 Mary Douglas 1966 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0-415-06608-5 (Print Edition) ISBN 0-203-12938-5 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-17578-6 (Glassbook Format) Contents Acknowledgements vii Introduction 1 1. -

Bringing Cultural Practice Into Law: Ritual and Social Norms Jurisprudence Andrew J

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 43 | Number 2 Article 2 1-1-2003 Bringing Cultural Practice Into Law: Ritual and Social Norms Jurisprudence Andrew J. Cappel Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew J. Cappel, Bringing Cultural Practice Into Law: Ritual and Social Norms Jurisprudence, 43 Santa Clara L. Rev. 389 (2003). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol43/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRINGING CULTURAL PRACTICE INTO LAW: RITUAL AND SOCIAL NORMS JURISPRUDENCE Andrew J. Cappel* I. INTRODUCTION The past decade has witnessed an explosive growth in legal scholarship dealing with the problem of informal social norms and their relationship to formal law.1 This article highlights a sa- * Associate Professor of Law, St. Thomas University Law School. J.D., Yale Law School; M.Phil., Yale University; B.A., Yale College. I would like to thank Bruce Ackerman and Stanley Fish, both of whom read prior versions of this paper, for their help and advice. I also wish to thank Robert Ellickson for his encourage- ment in this project. In addition, valuable suggestions were made by participants when a version of this paper was presented at the 2000 Law and Society conference in Miami. Among the many of my present and former colleagues at St. -

CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: the Man and His Works

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 1977 CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works Susan M. Voss University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Voss, Susan M., "CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works" (1977). Nebraska Anthropologist. 145. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/145 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE NEBRASKA ANTHROPOLOGIST, Volume 3 (1977). Published by the Anthropology Student Group, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 21 / CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works by Susan M. Voss 'INTRODUCTION "Claude Levi-Strauss,I Professor of Social Anth- ropology at the College de France, is, by com mon consent, the most distinguished exponent ~f this particular academic trade to be found . ap.ywhere outside the English speaking world ... " (Leach 1970: 7) With this in mind, I am still wondering how I came to be embroiled in an attempt not only to understand the mul t:ifaceted theorizing of Levi-Strauss myself, but to interpret even a portion of this wide inventory to my colleagues. ' There is much (the maj ori ty, perhaps) of Claude Levi-Strauss which eludes me yet. To quote Edmund Leach again, rtThe outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or in English, is that it is difficul tto unders tand; his sociological theories combine bafflingcoinplexity with overwhelm ing erudi tion"., (Leach 1970: 8) . -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Between Purity and Danger: Fieldwork Approaches to Movement

Isidoros, Between purity and danger BETWEEN PURITY AND DANGER: FIELDWORK APPROACHES TO MOVEMENT, PROTECTION AND LEGITIMACY FOR A FEMALE ETHNOGRAPHER IN THE SAHARA DESERT KONSTANTINA ISIDOROS ‘What truly distinguishes anthropology […] is that it is not a study of at all, but a study with. Anthropologists work and study with people.’ (Ingold 2011: 238) Introduction Although Mary Douglas (2002 [1966]) led the anthropological study of ‘purity and danger’ to explore the meaning of dirt in different contexts, it is a revealing lens to apply to another taboo – the erotic subjectivity of researchers (Kulick and Willson 1995). Of relevance here is Douglas’ starting point: what is regarded as dirt in a given society is ‘matter out of place’. Most human beings have an interest in sex, and anthropology has long studied sex in both distant and home field sites.1 Yet the sexual life of researchers during fieldwork remains a consummate example of ‘matter out of place’, a matter complicated by idiosyncratic sexual sensibilities. I reflect upon this ambiguity as sexual absence – or rather, as asexual presence – compelled by the authoritative imperative for scientific ‘purity’ (integrity). In this scenario, sexual relations between researcher and researched are seen as dangerous, polluting anthropological data as ‘dirt’. This article explores a debate in a small body of scholarship concerning sex[ual danger] in the field. In it I argue that this ‘matter out of place’, instead of jeopardising the integrity of the research, has the potential to offer rich ethnographic insight, hence it should be written up rather than written out. I suggest that, to understand what types of sex[ual danger] the researcher may encounter in the field, an anthropological ‘sex education’ prior to fieldwork would be helpful to comprehend both one’s own and others’ cultural perceptions and practices of sex. -

Descent Systems and Ideal Language Rodney Needham Philosophy of Science, Vol

Descent Systems and Ideal Language Rodney Needham Philosophy of Science, Vol. 27, No. 1. (Jan., 1960), pp. 96-101. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0031-8248%28196001%2927%3A1%3C96%3ADSAIL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-F Philosophy of Science is currently published by The University of Chicago Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/ucpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Tue Mar 25 07:12:03 2008 DISCUSSION DESCENT SYSTEMS AND IDEAL LANGUAGE* RODNEY NEEDHAM University of Oxford This note is written in response to Gellner's "Ideal Language and Kinship Structure" (l).l In that article he tries to shed some light on the notion of an ideal language by constructing in outline an ideal language for what he calls "kinship structure theory". -

Symbolic Anthropology Symbolic Anthropology Victor Turner (1920

Symbolic Anthropology • Examines symbols & processes by which humans assign meaning. • Addresses fundamental Symbolic anthropology questions about human social life, especially through myth & ritual. ANTH 348/Ideas of Culture • Culture does not exist apart from individuals. • It is found in interpretations of events & things around them. Symbolic Anthropology Victor Turner (1920-1983) • Studied with Max Gluckman @ Manchester University. • Culture is a system of meaning deciphered by • Taught at: interpreting key symbols & rituals. • Stanford University • Anthropology is an interpretive not scientific • Cornell University • University of Chicago endeavor . • University of Virginia. • 2 dominant trends in symbolic anthropology • Publications include: • Schism & Continuity in an African Society (1957) represented by work of British anthropologist • The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual (1967) Victor Turner & American anthropologist • The Drums of Affliction: A Study of Religious Processes Among the Ndembu of Zambia Clifford Geertz. (1968) • The Ritual Process: Structure & Anti-Structure (1969). • Dramas, Fields, & Metaphors (1974) • Revelation & Divination in Ndembu Ritual (1975) Social Drama Social drama • • Early work on village-level social processes among the For Turner, social dramas have four main phases: Ndembu people of Zambia 1. Breach –rupture in social relations. examination of demographics & economics. 2. Crisis – cannot be handled by normal strategies. • Later shift to analysis of ritual & symbolism. 3. Redressive action – seeks to remedy the initial problem, • Turner introduced idea of social drama redress and re-establish • "public episodes of tensional irruption*” 4. Reintegration or schism – return to status quo or an • “units of aharmonic or disharmonic process, arising in conflict situations.” alteration in social arrangements. • They represent windows into social organization & values . -

Anthropology and Folklore Studies in India: an Overview

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN: 2319-7064 ResearchGate Impact Factor (2018): 0.28 | SJIF (2019): 7.583 Anthropology and Folklore Studies in India: An Overview Kundan Ghosh1, Pinaki Dey Mullick2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Mahishadal Girls‟ College, Rangibasan, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India 2Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Haldia Government College, Haldia, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal, India Abstract: Anthropology has a long tradition of folklore studies. Anthropologist studied both the aspect of folklore i.e. life and lore. Folklore became a popular medium in anthropological studies and using emic approach researchers try to find out the inner meaning of different aspects of culture. This paper focused on the major approaches of the study of Anthropology and Folklore. It is an attempt to classify different phases of Anthropology of Folklore studies in India and understand the historical development of Anthropology of Folklore studies in India. It is observed that, both theoretical and methodological approaches were changed with the time and new branches are emerged with different dimensions. Keywords: Folklore, emic approach, lore, Anthropology of Folklore, culture. 1. Introduction closure term „folklore‟. Folklore includes both verbal and non-verbal forms. Oral literature, however, is usually Of the four branches of Anthropology, Cultural includes verbal folklore only and does not include games Anthropology is most closely associated with folklore and dances. Different cultures have different categories of (Bascom, 1953). The term folklore was coined by W. J. folk literature. Dundes is of the opinion that contemporary Thoms in the year 1846 and was used by him in the study of oral literature tends to see folklore as a reflection of magazine entitled The Athenaenum of London. -

Revisiting Mary Douglas

Review article Elementary forms and their dynamics: revisiting Mary Douglas by Perri 6 Professor in Public Management School of Business and Management Queen Mary, University of London E-mail: [email protected] Accepted for publication in Anthropological forum , 28.5.2014 Acknowledgements I am grateful to Mitchell Low and to Greg Acciaioli for commissioning this review article and for their comments on an earlier draft, and to Paul Richards for many invaluable suggestions. Elementary forms and their dynamics: revisiting Mary Douglas Review article on Fardon R, ed, 2013, Mary Douglas: cultures and crises – understanding risk and resolution , London: Sage and Fardon R, ed, 2013, Mary Douglas: a very personal method – anthropological writings drawn from life , London: Sage. Keywords Mary Douglas; neo-Durkheimian institutional theory; institutions; social dynamics; hierarchy; enclave; isolate; individualism; Abstract Mary Douglas’s oeuvre furnishes the social sciences with one of the most profound and ambitious bodies of social theory ever to emerge from within anthropology. This article uses the occasion of the publication of Fardon’s two volumes of her previously uncollected papers to restate her core arguments about the limited plurality of elementary forms of social organisation and about the institutional dynamics of conflict and about conflict attenuation. In reviewing these two volumes, the article considers what those anthropologists who have been sceptical either of Douglas’s importance or of the Durkheimian traditions generally will want from these books to convince them to look afresh at her work. It concludes that the two collections will provide open-minded anthropologists with enough evidence of the creativity and significance of her achievement to encourage them to reopen her major theoretical works. -

Polysensoriality

CHAPTER 25 THE SENSES: Polysensoriality David Howes As Bryan Turner (1997: 16) has observed, one cannot take "the body" for granted as a "natural, fixed and historically universal datum of human societies." The classification of the body's senses is a case in point. "Sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch: that the senses should be enumerated in this way is not self-evident. The number and order of the senses are fixed by custom and tradition, not by nature" (Vinge 1975: 107). Plato, for example, apparently did not distinguish clearly between the senses and feelings. "In one enumeration of perceptions, he begins with sight, hearing and smell, leaves out taste, instead of touch mentions hot and cold, and adds sensations of pleasure, discomfort, desire and fear" (Classen 1993a: 2). It is largely thanks to the works of Aristotle that the notion of the senses being five in number, and of each sense as having its proper object (i.e. sight being concerned with color, hearing with sound, smell with odor, etc.) came to figure as a commonplace of Western culture. Even so, Aristotle classified taste as "a form of touch"; hence, it would be more accurate to speak of "the four senses" in his enumeration. So, too, was there considerable diversity of opinion in antiquity regarding the order of the senses (i.e. sight as the most informative of the modalities, followed by hearing, smell, and so on down the scale). Diogenes, for example, apparently placed smell in first place followed by hearing, and other philosophers proposed other hierarchies; what would become the standard ranking was given its authority (once again) by Aristotle (Vinge 1975: 17–19). -

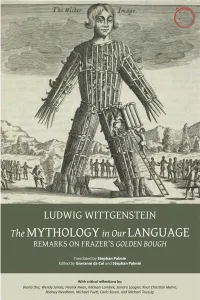

The Mythology in Our Language

THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE THE MYTHOLOGY IN OUR LANGUAGE Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough Translated by Stephan Palmié Edited by Giovanni da Col and Stephan Palmié With critical reflections by Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Hau Books Chicago © 2018 Hau Books and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Stephan Palmié, Giovanni da Col, Veena Das, Wendy James, Heonik Kwon, Michael Lambek, Sandra Laugier, Knut Christian Myhre, Rodney Needham, Michael Puett, Carlo Severi, and Michael Taussig Cover: “A wicker man, filled with human sacrifices (071937)” © The British Library Board. C.83.k.2, opposite 105. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Editorial office: Michelle Beckett, Justin Dyer, Sheehan Moore, Faun Rice, and Ian Tuttle Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-1-912808-40-3 LCCN: 2018962822 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is printed, marketed, and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Preface xi chapter 1 Translation is Not Explanation: Remarks on the Intellectual History and Context of Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer 1 Stephan Palmié chapter 2 Remarks on Frazer’s The Golden Bough 29 Ludwig Wittgenstein, translated by Stephan Palmié chapter 3 On Wittgenstein’s Remarks on Frazer’s Golden Bough 75 Carlo Severi chapter 4 Wittgenstein’s -

INTRODUCTION Drawn from Life: Mary Douglas's Personal Method

INTRODUCTION Drawn from life: Mary Douglas’s personal method Richard Fardon Mary Douglas (1921–2007) was the most widely read British anthropolo- gist of the second half of the twentieth century. Her writings continue to inspire researchers in numerous fields in the twenty-first century.1 This vol- ume of papers, first published over a period of almost fifty years, provides insights into the wellsprings of her style of thought and manner of writing. More popular counterparts to many of Douglas’s academic works – either the first formulation of an argument, or its more general statement – were often published around the same time as a specialist version. These first thoughts and popular re-imaginings are particularly revealing of the close relation between Douglas’s intellectual and personal concerns, a convergence that became more overt in her late career, when Mary Douglas occasionally wrote autobiographi- cally, explaining her ideas in relation to her upbringing, her family, and her experiences as both a committed Roman Catholic and a social anthropologist in the academy. The four social types of her theoretical writings – hierarchy, competition, the enclaved sect, and individuals in isolation – extend to remote times and distant places, prototypes that literally were close to home for her. This ability to expand and contract a restricted range of formal images allowed Mary Douglas to enter new fields of study with startling rapidity, to link unlikely domains of thought (through analogy, most frequently with religion), and to accommodate the most diverse examples in comparative frameworks. It was the way, to put it baldly, she made things fall into place.