A High Gain CMOS Operational Amplifier with Negative Conductance Gain Enhancement Jie Yan and Randall L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.5A, 24V, 17Mhz Power Operational Amplifier Datasheet (Rev. E)

OPA564 www.ti.com SBOS372E –OCTOBER 2008–REVISED JANUARY 2011 1.5A, 24V, 17MHz POWER OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIER Check for Samples: OPA564 1FEATURES 23• HIGH OUTPUT CURRENT: 1.5A DESCRIPTION • WIDE POWER-SUPPLY RANGE: The OPA564 is a low-cost, high-current operational – Single Supply: +7V to +24V amplifier that is ideal for driving up to 1.5A into reactive loads. The high slew rate provides 1.3MHz – Dual Supply: ±3.5V to ±12V full-power bandwidth and excellent linearity. These • LARGE OUTPUT SWING: 20VPP at 1.5A monolithic integrated circuits provide high reliability in • FULLY PROTECTED: demanding powerline communications and motor control applications. – THERMAL SHUTDOWN – ADJUSTABLE CURRENT LIMIT The OPA564 operates from a single supply of 7V to 24V, or dual power supplies of ±3.5V to ±12V. In • DIAGNOSTIC FLAGS: single-supply operation, the input common-mode – OVER-CURRENT range extends to the negative supply. At maximum – THERMAL SHUTDOWN output current, a wide output swing provides a 20VPP (I = 1.5A) capability with a nominal 24V supply. • OUTPUT ENABLE/SHUTDOWN CONTROL OUT • HIGH SPEED: The OPA564 is internally protected against over-temperature conditions and current overloads. It – GAIN-BANDWIDTH PRODUCT: 17MHz is designed to provide an accurate, user-selected – FULL-POWER BANDWIDTH AT 10VPP: current limit. Two flag outputs are provided; one 1.3MHz indicates current limit and the second shows a – SLEW RATE: 40V/ms thermal over-temperature condition. It also has an Enable/Shutdown pin that can be forced low to shut • DIODE FOR JUNCTION TEMPERATURE down the output, effectively disconnecting the load. MONITORING The OPA564 is housed in a thermally-enhanced, • HSOP-20 PowerPAD™ PACKAGE surface-mount PowerPAD™ package (HSOP-20) with (Bottom- and Top-Side Thermal Pad Versions) the choice of the thermal pad on either the top side or the bottom side of the package. -

Designing Linear Amplifiers Using the IL300 Optocoupler Application Note

Application Note 50 Vishay Semiconductors Designing Linear Amplifiers Using the IL300 Optocoupler INTRODUCTION linearizes the LED’s output flux and eliminates the LED’s This application note presents isolation amplifier circuit time and temperature. The galvanic isolation between the designs useful in industrial, instrumentation, medical, and input and the output is provided by a second PIN photodiode communication systems. It covers the IL300’s coupling (pins 5, 6) located on the output side of the coupler. The specifications, and circuit topologies for photovoltaic and output current, IP2, from this photodiode accurately tracks the photoconductive amplifier design. Specific designs include photocurrent generated by the servo photodiode. unipolar and bipolar responding amplifiers. Both single Figure 1 shows the package footprint and electrical ended and differential amplifier configurations are discussed. schematic of the IL300. The following sections discuss the Also included is a brief tutorial on the operation of key operating characteristics of the IL300. The IL300 photodetectors and their characteristics. performance characteristics are specified with the Galvanic isolation is desirable and often essential in many photodiodes operating in the photoconductive mode. measurement systems. Applications requiring galvanic isolation include industrial sensors, medical transducers, and IL300 mains powered switchmode power supplies. Operator safety 1 8 and signal quality are insured with isolated interconnections. These isolated interconnections commonly use isolation 2 K2 7 amplifiers. K1 Industrial sensors include thermocouples, strain gauges, and pressure transducers. They provide monitoring signals to a 3 6 process control system. Their low level DC and AC signal must be accurately measured in the presence of high 4 5 common-mode noise. -

NTE7144 Integrated Circuit BIMOS Operational Amplifier W/MOSFET Input, Bipolar Output

NTE7144 Integrated Circuit BIMOS Operational Amplifier w/MOSFET Input, Bipolar Output Description: The NTE7144 is an integrated circuit operational amplifier in an 8–Lead Mini–DIP type package that combines the advantages of high–voltage PMOS transistors with high–voltage bipolar transistors on a single monolithic chip. This device features gate–protected MOSFET (PMOS) transistors in the in- put circuit to provide very–high–input impedance, very–low–input current, and high–speed perfor- mance. The NTE7144 operates at supply voltages from 4V to 36V (either single or dual supply) and is internally phase–compensated to achieve stable operation in unity–gain follower operation. The use of PMOS field–effect transistors in the input stage results in common–mode input–voltage capability down to 0.5V below the negative–supply terminal, an important attribute for single–supply applications. The output stage uses bipolar transistors and includes built–in protection against dam- age from load–terminal short–circuiting to either supply–rail or to GND. Features: D MOSFET Input Stage: Very High Input Impedance Very Low Input Current Wide Common–Mode Input Voltage Range Output Swing Complements Input Common–Mode Range D Directly Replaces Industry Type 741 in Most Applications Applications: D Ground–Referenced Single–Supply Amplifiers in Automobile and Portable Instrumentation D Sample and Hold Amplifiers D Long–Duration Timers/Multivibrators (Microseconds – Minutes – Hours) D Photocurrent Instrumentation D Peak Detectors D Active Filters D Comparators D Interface in 5V TTL Systems and other Low–Supply Voltage Systems D All Standard Operational Amplifier Applications D Function Generators D Tone Controls D Power Supplies D Portable Instruments D Intrusion Alarm Systems Absolute Maximum Ratings: DC Supply Voltage (Between V+ and V– Terminals). -

Example of a MOSFET Operational Amplifier

Example of a MOSFET Operational Amplifier: This circuit is one I “designed” as an example for Engineering 1620. It is certainly not fully optimized and I am not sure it is free of errors. It is based on a 1.5 micron, P-well process and therefore uses an N-channel differential pair for its input. This is somewhat unusual because P-channel devices have lower intrinsic noise and are the device-type of choice for the input stage. I did this simply to avoid doing your SPICE assignment for you. The overall properties of the circuit are given in the table below. Amplifier Property Value A0 – DC Gain 86 DB (X20,000) fp – dominant pole position 400 Hz fGBW 8.0 MHz fU – unity gain frequency 5.6 MHz Output stage resistance at low frequency 277 K Zero position 10.7 MHz Slew Rate 710 6 V/sec Output stage quiescent current 65 a Opamp quiescent current 103 a Bias circuit quiescent current 104 a Total system quiescent current 210 a VDD 5.0 volts Total system power 1.1 mW MOSFET Operational Amplifier Gain and Phase 10 0 18 0 80 12 0 60 Gain 60 Phase 40 0 Gain (DB) 20 -60 Phase (deg.) 0 -120 -20 -180 1.00E+02 1.00E+03 1.00E+04 1.00E+05 1.00E+06 1.00E+07 1.00E+08 Frequency (Hz) Phase margin = 60 deg. Parameter Table for MOSFET Opamp Example element model vds vgs vth vov id gm ro m1 nssb 0.748 0.851 0.547 0.304 3.77E-05 2.90E-04 5.54E+05 m10 nssb 3.368 0.851 0.547 0.304 4.12E-05 3.11E-04 8.09E+05 m12 nssb 0.711 0.711 0.546 0.165 3.51E-05 5.01E-04 5.05E+05 m13 nssb 0.838 0.851 0.547 0.304 3.79E-05 2.91E-04 5.92E+05 m14 nssb 3.078 1.079 0.840 0.239 3.51E-05 -

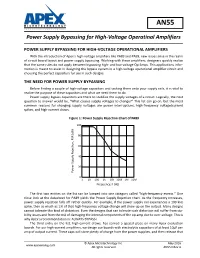

AN55 Power Supply Bypassing for High-Voltage Operational Amplifiers

AN55 Power Supply Bypassing for High-Voltage Operatinal Amplifiers POWER SUPPLY BYPASSING FOR HIGH-VOLTAGE OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIERS With the introduction of Apex’s high-voltage amplifiers like PA89 and PA99, new issues arise in the realm of circuit board layout and power supply bypassing. Working with these amplifiers, designers quickly realize that the same rules do not apply between bypassing high- and low-voltage Op-Amps. This applications infor- mation is meant to assist in designing the bypass system in a high-voltage operational amplifier circuit and choosing the perfect capacitors for use in such designs. THE NEED FOR POWER SUPPLY BYPASSING Before finding a couple of high-voltage capacitors and tacking them onto your supply rails, it is vital to realize the purpose of these capacitors and what we need them to do. Power supply bypass capacitors are there to stabilize the supply voltages of a circuit. Logically, the next question to answer would be, “What causes supply voltages to change?” This list can go on, but the most common reasons for changing supply voltages are power interruptions, high-frequency voltage/current spikes, and high-current draws. Figure 1: Power Supply Rejection Chart of PA89 100 80 60 40 20 WŽǁĞƌ^ƵƉƉůLJZĞũĞĐƟŽŶ͕W^Z;ĚͿ 0 1 10100 1k 10k 100k1M 10M Frequency, F (Hz) The first two entries on the list can be lumped into one category called “high-frequency events.” One close look at the datasheet for PA89 yields the Power Supply Rejection chart. As the frequency increases, power supply rejection falls off rather quickly. For example, if the power supply rail experiences a 100 kHz spike, then as much as 1% of that high-frequency voltage change will show up on the output. -

A Differential Operational Amplifier Circuit Collection

Application Report SLOA064A – April 2003 A Differential Op-Amp Circuit Collection Bruce Carter High Performance Linear Products ABSTRACT All op-amps are differential input devices. Designers are accustomed to working with these inputs and connecting each to the proper potential. What happens when there are two outputs? How does a designer connect the second output? How are gain stages and filters developed? This application note answers these questions and gives a jumpstart to apprehensive designers. 1 INTRODUCTION The idea of fully-differential op-amps is not new. The first commercial op-amp, the K2-W, utilized two dual section tubes (4 active circuit elements) to implement an op-amp with differential inputs and outputs. It required a ±300 Vdc power supply, dissipating 4.5 W of power, had a corner frequency of 1 Hz, and a gain bandwidth product of 1 MHz(1). In an era of discrete tube or transistor op-amp modules, any potential advantage to be gained from fully-differential circuitry was masked by primitive op-amp module performance. Fully- differential output op-amps were abandoned in favor of single ended op-amps. Fully-differential op-amps were all but forgotten, even when IC technology was developed. The main reason appears to be the simplicity of using single ended op-amps. The number of passive components required to support a fully-differential circuit is approximately double that of a single-ended circuit. The thinking may have been “Why double the number of passive components when there is nothing to be gained?” Almost 50 years later, IC processing has matured to the point that fully-differential op-amps are possible that offer significant advantage over their single-ended cousins. -

9 Op-Amps and Transistors

Notes for course EE1.1 Circuit Analysis 2004-05 TOPIC 9 – OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIER AND TRANSISTOR CIRCUITS . Op-amp basic concepts and sub-circuits . Practical aspects of op-amps; feedback and stability . Nodal analysis of op-amp circuits . Transistor models . Frequency response of op-amp and transistor circuits 1 THE OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIER: BASIC CONCEPTS AND SUB-CIRCUITS 1.1 General The operational amplifier is a universal active element It is cheap and small and easier to use than transistors It usually takes the form of an integrated circuit containing about 50 – 100 transistors; the circuit is designed to approximate an ideal controlled source; for many situations, its characteristics can be considered as ideal It is common practice to shorten the term "operational amplifier" to op-amp The term operational arose because, before the era of digital computers, such amplifiers were used in analog computers to perform the operations of scalar multiplication, sign inversion, summation, integration and differentiation for the solution of differential equations Nowadays, they are considered to be general active elements for analogue circuit design and have many different applications 1.2 Op-amp Definition We may define the op-amp to be a grounded VCVS with a voltage gain (µ) that is infinite The circuit symbol for the op-amp is as follows: An equivalent circuit, in the form of a VCVS is as follows: The three terminal voltages v+, v–, and vo are all node voltages relative to ground When we analyze a circuit containing op-amps, we cannot use the -

Fully-Differential Amplifiers

Application Report S Fully-Differential Amplifiers James Karki AAP Precision Analog ABSTRACT Differential signaling has been commonly used in audio, data transmission, and telephone systems for many years because of its inherent resistance to external noise sources. Today, differential signaling is becoming popular in high-speed data acquisition, where the ADC’s inputs are differential and a differential amplifier is needed to properly drive them. Two other advantages of differential signaling are reduced even-order harmonics and increased dynamic range. This report focuses on integrated, fully-differential amplifiers, their inherent advantages, and their proper use. It is presented in three parts: 1) Fully-differential amplifier architecture and the similarities and differences from standard operational amplifiers, their voltage definitions, and basic signal conditioning circuits; 2) Circuit analysis (including noise analysis), provides a deeper understanding of circuit operation, enabling the designer to go beyond the basics; 3) Various application circuits for interfacing to differential ADC inputs, antialias filtering, and driving transmission lines. Contents 1 Introduction . 3 2 What Is an Integrated, Fully-Differential Amplifier? . 3 3 Voltage Definitions . 5 4 Increased Noise Immunity . 5 5 Increased Output Voltage Swing . 6 6 Reduced Even-Order Harmonic Distortion . 6 7 Basic Circuits . 6 8 Circuit Analysis and Block Diagram . 8 9 Noise Analysis . 13 10 Application Circuits . 15 11 Terminating the Input Source . 15 12 Active Antialias Filtering . 20 13 VOCM and ADC Reference and Input Common-Mode Voltages . 23 14 Power Supply Bypass . 25 15 Layout Considerations . 25 16 Using Positive Feedback to Provide Active Termination . 25 17 Conclusion . 27 1 SLOA054E List of Figures 1 Integrated Fully-Differential Amplifier vs Standard Operational Amplifier. -

E Basic Circuit of an Operational Amplifier Is As Shown in Above Fig

www.getmyuni.com UNIT - 1 OPERATIONAL AMPLIFIER FUNDAMENTALS 1.1 Basic operational amplifier circuit- heT basic circuit of an operational amplifier is as shown in above fig. has a differential amplifier input stage and an emitter follower output. Supply voltages +Vcc and -Vcc are provided. Transistors Q1 and Q2 constitute a differential amplifier, which produces a voltage change as the collector of Q2 where a difference input voltage is applied to the bases of Q1 and Q2. Transistor Q2 operates as an emitter follower to provide low output impedance. Vo = Vcc –VRC –VBE3 = Vcc – IC2Rc – VBE Assume that Q1 and Q2 are matched transistors that are they have equal VBE levels and equalcurrent gains. With both transistor bases at ground level, the emitter currents are equal and both IE1 and IE2 flow through the common emitter resistor RE. The emitter current is given by:- www.getmyuni.com IE1 + IE2 = VRE/RE With Q1 and Q2 bases grounded, 0 – VBE – VRE + VEE = 0 VEE – VBE = VRE VRE = VEE – VBE IE1 + IE2 = – Vcc = 10 V, VEE = - 10 V, RE = 4.7 K, Rc = 6.8 K, VBE = 0.7, IE1 + IE2 = (10 – 0.7)/4.7 K + 2 mA IE1 = IE2 = 1mA Ic2 = IE2 = 1 mA Vo = 10 – 1mA x 6.8 K – 0.7 Vo = 2.5 V If a positive going voltage is applied to the non-inverting input terminal, Q1 base is pulled up by the input voltage and its emitter terminal tends to follow the input signal. Since Q1 and Q2 emitters are connected together, the emitter of Q2 is also pulled up by the positive going signal at the non-inverting input terminal. -

Effect of Parasitic Capacitance in Op Amp Circuits (Rev. A)

Application Report SLOA013A - September 2000 Effect of Parasitic Capacitance in Op Amp Circuits James Karki Mixed Signal Products ABSTRACT Parasitic capacitors are formed during normal operational amplifier circuit construction. Operational amplifier design guidelines usually specify connecting a small 20-pF to 100-pF capacitor between the output and the negative input, and isolating capacitive loads with a small, 20-Ω to 100-Ω resistor. This application report analyzes the effects of capacitance present at the input and output pins of an operational amplifier, and suggests means for computing appropriate values for specific applications. The inverting and noninverting amplifier configurations are used for demonstration purposes. Other circuit topologies can be analyzed in a similar manner. Contents 1 Introduction . 3 2 Basic One-Pole Operational Amplifier Model. 3 3 Basic Circuits and Analysis. 4 3.1 Gain Analysis . 5 3.1.1 Stability Analysis. 6 4 Capacitance at the Inverting Input. 7 4.1 Gain Analysis With Cn. 7 4.1.1 Stability Analysis With Cn. 10 4.1.2 Compensating for the Effects of Cn. 11 5 Capacitance at the Noninverting Input. 14 5.1 Gain Analysis With Cp. 14 5.2 Stability Analysis With Cp. 15 5.3 Compensating for the Effects of Cp. 15 6 Output Resistance and Capacitance. 16 6.1 Gain Analysis With Ro and Co. 16 6.2 Stability Analysis With Ro and Co. 18 6.3 Compensation for Ro and Co. 19 7 Summary . 24 8 References . 25 List of Figures 1 Basic Dominant-Pole Operational Amplifier Model. 4 2 Amplifier Circuits Constructed With Negative Feedback. -

Operational Amplifier Circuits

Operational Amplifier Circuits Review: Ideal Op-amp in an open loop configuration Ip Vp + + + Ro Vo Vi Ri _ AVi Vn _ In An ideal op-amp is characterized with infinite open–loop gain A →∞ The other relevant conditions for an ideal op-amp are: 1. Ip =In =0 2. Ri =∞ 3. Ro = 0 Ideal op-amp in a negative feedback configuration When an op-amp is arranged with a negative feedback the ideal rules are: 1. Ip =In =0 : input current constraint 2. Vn = Vp : input voltage constraint These rules are related to the requirement/assumption for large open-loop gain A →∞, and they form the basis for op-amp circuit analysis. The voltage Vn tracks the voltage Vp and the “control” of Vn is accomplished via the feedback network. Chaniotakis and Cory. 6.071 Spring 2006 Page 1 Operational Amplifier Circuits as Computational Devices So far we have explored the use of op amps to multiply a signal by a constant. For the R2 inverting amplifier the multiplication constant is the gain − R1 and for the non inverting R2 amplifier the multiplication constant is the gain 1+ R1 . Op amps may also perform other mathematical operations ranging from addition and subtraction to integration, differentiation and exponentiation.1 We will next explore these fundamental “operational” circuits. Summing Amplifier A basic summing amplifier circuit with three input signals is shown on Figure 1. I I R1 1 F RF Vin1 I R2 2 N V 1 in2 Vout R3 I3 Vin3 Figure 1. Summing amplifier Current conservation at node N1 gives I12+ II+=3IF (1.1) By relating the currents I1, I2 and I3 to their corresponding voltage and resistance by Ohm’s law and noting that the voltage at node N1 is zero (ideal op-amp rule) Equation (1.1) becomes VVV V in12++in in3=−out (1.2) R12RR3RF 1 The term operational amplifier was first used by John Ragazzini et. -

Fully Differential Operational Amplifiers with Accurate Output Balancing

1410 IEEE JOURNAL OF SOLID-STATE CIRCUITS, VOL. 23. NO. 6, DECEMBER 1988 TABLE I 131 A. J. M. Boomkamp and Ci. C. M. Meijer. “An accurate biomedical temperature transducer with on-chip microcomputer interface,” in Dig. Tech. Puperx. Europeun Solrd-Stute Circurts Conf.. Sept. 1985, pp. 214-217. supply voltage 2.5 - 3.1 V [41 G. C. M. Meijer, R. van Gelder, V. Nooder. J. van Drecht, and H. M. supply current 200 PA M. Kerkvliet. “A three-terminal wide-range temperature transducer with temperature range 32OC to 44OC microcomputer interfacing.” in Dig. Tech. Puper.y, Europeun Solid-Stute Circurts Conf., Sept. 1986, pp. 161-163. accuracy t O.I’C, see text M. J. S. Smith, L. Bowman, and J. D. Meindl, “Analysis, design and error due to supply voltage changes 0.04OC performance of micropower circuits for a capacitive pressure sensor IC,” [for the voltage range 2.5V-3.1VI IEEE J. Solrd-Sture Circuits, vol. SC-21, pp. 1045-1056, Dec. 1986. G. C. M. Meijer, “An IC temperature transducer with an intrinsic O.0l0C reference.” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. SC-15, pp. 370-373, June [for the voltage range 2.6V-3.3VI 1980. reference frequency 30 kHz G. C. M. Meijer and K. Vingerling, “Measurement of the temperature dependence of the IC( VRE)characteristics of integrated bipolar transis- frequency ratio p 12(R /R )(T - TZ)/TZ 42 tors,” IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits, vol. SC-15, pp. 237-240, Apr. 1980. G. C. M. Meijer, “Thermal sensors based on transistors,” Sensor.\ und Actuutors.