Columbia FDI Profiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Start Typing Letter Here

Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Por más de cuatro décadas Patricia Phelps de Cisneros ha sido promotora de la educación y del arte, con un enfoque particular en América Latina. En la década de los setenta estableció, junto con su esposo Gustavo Cisneros, la Fundación Cisneros con sede en Caracas y Nueva York. La misión de la Fundación es contribuir a la educación en América Latina y dar a conocer el patrimonio cultural latinoamericano y sus múltiples contribuciones a la cultura global. La Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros, fundada a principios de la década de los noventa, es la principal iniciativa cultural de la Fundación Cisneros. Primeras influencias, trabajo y educación William Henry Phelps (1875-1965), bisabuelo de Patricia Cisneros, emprendió una expedición ornitológica en Venezuela, tras concluir su tercer año de licenciatura en la Universidad de Harvard. En ese viaje se enamoró del país y, al concluir sus estudios, regresó para asentarse permanentemente en el país. Phelps fue el gran emprendedor de su época, desarrollando prácticas modernas de negocios y estableciendo varias compañías, desde emisoras de televisión y estaciones de radio hasta importadoras de automóviles, refrigeradores, victrolas, máquinas de escribir, además que fue pionero en introducir el gusto por el béisbol en el país. Creó también la primera fundación en Venezuela. Su profundo interés por las ciencias naturales lo llevó a convertirse en un notable ornitólogo, a catalogar muchas especies aviarias de Suramérica y a publicar sus descubrimientos junto a su mentor, el científico Frank M. Chapman, en el Museo de Historia Natural de Nueva York (AMNH por sus siglas en inglés). -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 to Generate Economic and Social Value Through Our Companies and Institutions

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 To generate economic and social value through our companies and institutions. We have established a mission, a vision and values that are both our beacons and guidelines to plan strategies and projects in the pursuit of success. Fomento Económico Mexicano, S.A.B. de C.V., or FEMSA, is a leader in the beverage industry through Coca-Cola FEMSA, the largest franchise bottler of Coca-Cola products in the world by volume; and in the beer industry, through ownership of the second largest equity stake in Heineken, one of the world’s leading brewers with operations in over 70 countries. We participate in the retail industry through FEMSA Comercio, comprising a Proximity Division, operating OXXO, a small-format store chain; a Health Division, which includes all drugstores and related operations; and a Fuel Division, which operates the OXXO GAS chain of retail service stations. Through FEMSA Negocios Estratégicos (FEMSA Strategic Businesses) we provide logistics, point-of-sale refrigeration solutions and plastics solutions to FEMSA’s business units and third-party clients. FEMSA’s 2018 integrated Annual Report reflects our commitment to strong corporate governance and transparency, as exemplified by our mission, vision and values. Our financial and sustainability results are for the twelve months ended December 31, 2018, compared to the twelve months ended December 31, 2017. This report was prepared in accordance with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards and the United Nations Global Compact, this represents our Communication on Progress for 2018. Contents Discover Our Corporate Identity 1 FEMSA at a Glance 2 Value Creation Highlights 4 Social and Environmental Value 6 Dear Shareholders 8 FEMSA Comercio 10 Coca-Cola FEMSA 18 FEMSA Strategic Businesses 28 FEMSA Foundation 32 Corporate Governance 40 Financial Summary 44 Management’s Discussion & Analysis 46 Contact 52 Over the past several decades, FEMSA has evolved from an integrated beverage platform to a multifaceted business with a broad set of capabilities and opportunities. -

Annual Report Enel Chile 2016 Annual Report Enel Chile 2016 Annual Report Santiago Stock Exchange ENELCHILE

2016 Annual Report Enel Chile 2016 Annual Report Enel Chile Annual Report Santiago Stock Exchange ENELCHILE Nueva York Stock Exchange ENIC Enel Chile S.A. was initially incorporated as Enersis Chile S.A. on March 1st, 2016 and changed to Enel Chile S.A. on October 18th, 2016. As of December 31st, 2016, the total share capital of the Company was Th$ 2,229,108,975 represented by 49,092,772,762 shares. Its shares trade on the Santiago Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange as American Depositary Receipts (ADR). The main business of the Company is the development, operation, generation, distribution, transformation, or sale of energy in any form, directly or through other companies. Total assets of the Company amount to Th$ 5,398,711,012 as of December 31st, 2016. Enel Chile controls and manages a group of companies that operate in the Chilean electricity market. Net profit attributable to the controlling shareholder in 2016 reached Th$ 317,561,121 and operating income reached Th$ 457,202,938. At year-end 2016 the Company directly employed 2,010 people through its subsidiaries in Chile. Annual Report Enel Chile 2016 Summary > Letter from the Chairman 4 > Open Power 10 > Highlights 2016 12 > Main Financial and Operating Data 16 > Identification of the Company and Documents of Incorporation 20 > Ownership and Control 26 > Management 32 > Human Resources 54 > Stock Markets Transactions 64 > Dividends 70 > Investment and Financing Policy 76 > History of the Company 80 > Investments and Financial Activity 84 > Risk Factors 92 > Corporate -

Telenovelas Venezolanas En España: Producción Y Cuotas De Mercado En Las Televisiones Autonómicas

Anuario electrónico de estudios en Comunicación Social ISSN: 1856-9536 / p. pi 200808TA119 Volumen 4 , Número 1 / Enero-Junio 2011 Versión PDF para imprimir desde http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/Disertaciones Morales Morante. L. F. (2011). Telenovelas venezolanas en España: Producción y cuotas de mercado en las Televisiones Autonómicas. Anuario Electrónico de Estudios en Comunicación Social "Disertaciones" , 4 (1), Artículo 8. Disponible en la siguiente dirección electrónica: http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/Disertaciones/ TELENOVELAS VENEZOLANAS EN ESPAÑA: PRODUCCIÓN Y CUOTAS DE MERCADO EN LAS TELEVISIONES AUTONÓMICAS VENEZUELAN TELENOVELAS IN SPAIN: PRODUCTION AND MARKET SHARES IN THE AUTONOMIC TELEVISION MORALES MORANTE, Luis Fernando. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (España) [email protected] Página 177 Universidad de Los Andes - 2011 Anuario electrónico de estudios en Comunicación Social ISSN: 1856-9536 / p. pi 200808TA119 Volumen 4 , Número 1 / Enero-Junio 2011 Versión PDF para imprimir desde http://erevistas.saber.ula.ve/index.php/Disertaciones RESUMEN En los últimos años se ha constatado un incremento notable de telenovelas de origen venezolano o coproducciones hechas con empresas de este país en España. Concretamente, las televisiones de ámbito autonómico vienen operando como espacios de reutilización de diferentes títulos que en su momento fueron estrenados en las grandes cadenas nacionales, pero ahora, por su costo y la fragmentación de audiencias se instalan en estas televisoras. El estudio realizado entre los años 2008 y 2010 constata la presencia de 40 títulos que son analizados según sus rasgos de contenido, horas de emisión y franja horaria donde son insertados. Se definen además las marcas retóricas dominantes de este tipo de discursos de exportación y sus perspectivas comerciales de cara a los próximos años, en un escenario de ardua competencia y determinado por los ajustes de la televisión digital y las nuevas pantallas como Internet. -

Be a Disruptor Than to Defend Myself from Disruption.”

“I ultimately made the decision “The world that it would be more fun to wants us be a disruptor than to tell them that to defend myself the sky is falling. from disruption.” IT’s NOT.” – Le s L i e Mo o n v e s –Pe t e r Ch e r n i n aac e e s i ” – L “ . BEYO TECH NOL WELCOME NDDI OGY SRUP is the best ally democracy can have.” disruption and UNCERTAINTY good way to do it: embrace “There’s only one TION –Ad r i A n A Ci s n e r o s A Report on the AND PLEASE JOIN US INTERNATIONAL for the next International COUNCIL SUMMIT Council Summit September 14, 15, 16, 2011 April 26, 2012 Los Angeles Madrid, Spain CONTENTS A STEP BEYOND DISRUPTION 3 | A STEP BEYOND DISRUPTION he 2011 gathering of The Paley Center for Me- Tumblr feeds, and other helpful info. In addi- dia’s International Council marked the first time tion, we livestreamed the event on our Web site, 4 | A FORMULA FOR SUCCESS: EMBRacE DISRUPTION in its sixteen-year history that we convened in reaching viewers in over 140 countries. Los Angeles, at our beautiful home in Beverly To view archived streams of the sessions, visit 8 | SNAPSHOTS FROM THE COCKTAIL PaRTY AT THE PaLEY CENTER Hills. There, we assembled a group of the most the IC 2011 video gallery on our Web site at http:// influential thinkers in the global media and en- www.paleycenter.org/ic-2011-la-livestream. -

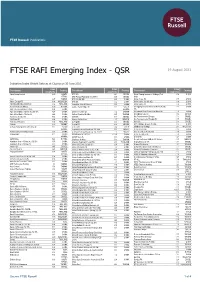

Emerging Index - QSR

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE RAFI Emerging Index - QSR Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index Index Index Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country weight (%) weight (%) weight (%) Absa Group Limited 0.29 SOUTH BRF S.A. 0.21 BRAZIL China Taiping Insurance Holdings (Red 0.16 CHINA AFRICA BTG Pactual Participations UNT11 0.09 BRAZIL Chip) Acer 0.07 TAIWAN BYD (A) (SC SZ) 0.03 CHINA China Tower (H) 0.17 CHINA Adaro Energy PT 0.04 INDONESIA BYD (H) 0.12 CHINA China Vanke (A) (SC SZ) 0.09 CHINA ADVANCED INFO SERVICE 0.16 THAILAND Canadian Solar (N Shares) 0.08 CHINA China Vanke (H) 0.2 CHINA Aeroflot Russian Airlines 0.09 RUSSIA Capitec Bank Hldgs Ltd 0.05 SOUTH Chongqing Rural Commercial Bank (A) (SC 0.01 CHINA Agile Group Holdings (P Chip) 0.04 CHINA AFRICA SH) Agricultural Bank of China (A) (SC SH) 0.27 CHINA Catcher Technology 0.2 TAIWAN Chongqing Rural Commercial Bank (H) 0.04 CHINA Agricultural Bank of China (H) 0.66 CHINA Cathay Financial Holding 0.29 TAIWAN Chunghwa Telecom 0.32 TAIWAN Air China (A) (SC SH) 0.02 CHINA CCR SA 0.14 BRAZIL Cia Paranaense de Energia 0.01 BRAZIL Air China (H) 0.06 CHINA Cemex Sa Cpo Line 0.7 MEXICO Cia Paranaense de Energia (B) 0.07 BRAZIL Airports of Thailand 0.04 THAILAND Cemig ON 0.03 BRAZIL Cielo SA 0.13 BRAZIL Akbank 0.18 TURKEY Cemig PN 0.18 BRAZIL CIFI Holdings (Group) (P Chip) 0.03 CHINA Al Rajhi Banking & Investment Corp 0.52 SAUDI Cencosud 0.04 CHILE CIMB Group Holdings 0.11 MALAYSIA ARABIA Centrais Eletricas Brasileiras S.A. -

2014-Carne-Negra-Fanzine-2-Pdf.Pdf

NO.2 2014 Sumario EXERGO..................................................................................................................................................3 Cinco dificultades para decir la verdad, Bertolt Brecht................................................................4 REFERENTES.........................................................................................................................................5 Estas láminas dicen mucho (fragmentos), José Veigas.................................................................6 HEBDOMAS...........................................................................................................................................12 ¿Quién tiene la culpa? Héctor Antón................................................................................................13 Narcotráfico S.A. – Nota preliminar, Recuerda el chocolate, Otari Oliva................................19 Narcotráfico S.A. La familia Cisneros: Los Bronfman de Venezuela, Lyndon LaRouche..22 La mente subdesarrollada (descontento y retractación), Ezequiel O. Suárez....................30 Mi obra brilla por su ausencia, Maldito Menéndez.......................................................................31 Campaña Free Internet Cuba, Maldito Menéndez......................................................................36 El mundo real de la política es otra historia, Jazmín Valdés.....................................................38 Contribución crítica libertaria a una historia del cinismo en Cuba, Mario -

Annual Report 2017

Annual Report Enel Chile 2017 Santiago Stock Exchange ENELCHILE Nueva York Stock Exchange ENIC Enel Chile S.A. was initially incorporated as Enersis Chile S.A., on March 1, 2016. On October 18, of the same year, the company changed its name to Enel Chile S.A. As of December 31, 2017 the company´s total subscribed and paid capital amounted to Ch$ 4,120,836,253 represented by 49,092,772,762 shares. These shares are traded on the Santiago Stock Exchange and, as American Depository Receipts (ADR) on the New York Stock Exchange. The company’s business is to exploit, develop, operate, generate, distribute, transform and/or sell energy, in any form and nature, directly or through other companies. Total assets as of December 31, 2017, amounted to ThCh $5,694,773,008 . Enel Chile controls and manages a group of companies that operate in the Chilean electricity market. In 2017, net income attributable to the controlling shareholder reached ThCh$ 349,382,642 and operating income was ThCh $578,630,574 . At year end 2017, a total 1,948 people were directly employed by its subsidiaries in Chile. Annual Report Enel Chile 2017 2 Annual Report Enel Chile 2017 Contents > Letter from the Chairman ....................................................................4 > Open Power ........................................................................................8 > Highlights 2017 ................................................................................10 > Main financial and operating data .....................................................14 -

Günther Maihold (Ed.) Venezuela En Retrospectiva. Los Pasos Hacia El Régimen Chavista

Günther Maihold (ed.) Venezuela en retrospectiva. Los pasos hacia el régimen chavista B I B L I O T H E C A I B E R O - A M E R I C A N A Publicaciones del Instituto Ibero-Americano Fundación Patrimonio Cultural Prusiano Vol. 118 B I B L I O T H E C A I B E R O - A M E R I C A N A Günther Maihold (ed.) Venezuela en retrospectiva Los pasos hacia el régimen chavista Iberoamericana · Vervuert 2007 Bibliografic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliografic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © Iberoamericana 2007 Amor de Dios, 1 E-28014 Madrid [email protected] www.ibero-americana.net © Vervuert Verlag 2007 Wielandstr. 40 D-60318 Frankfurt am Main [email protected] www.ibero-americana.net ISBN 978-84-8489-336-3 ISBN 978-3-86527-356-7 Diseño de la cubierta: Michael Ackermann Ilustración de la cubierta: ??? © ??? Composición: Anneliese Seibt, Instituto Ibero-Americano, Berlín Este libro está impreso íntegramente en papel ecológico blanqueado sin cloro Impreso en España CONTENIDO Günther Maihold Presentación. Venezuela y el desarrollo del proyecto chavista ................................. 7 1. La crisis del sistema político venezolano John Peeler Elementos estructurales de la desestabilización de una democracia consolidada: la desconsolidación en Venezuela ........................................................................................ 21 Ricardo Combellas El Proceso Constituyente y la Constitución de 1999 ........................ 47 Thais Maingon Síntomas de la crisis y la deslegitimación del sistema de partidos en Venezuela ....................................................................... 77 Günther Maihold ¿Por qué no aprenden las elites políticas? El caso de Venezuela ...................................................................................... -

Year Award Name Title - Organization

YEAR AWARD NAME TITLE - ORGANIZATION Innovative Leader of the Year H.E. Isabel de Saint Malo de Alvarado Vice President & Minister of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Panama 2 CEO of the Year Fabio Schvartsman CEO, Vale 0 Transformational Leader of the Eduardo Tricio Haro Chairman of the Board, Grupo Lala Year 1 Financier of the Year Eugenio von Chrismar CEO, Banco de Crédito e Inversiones (Bci) 8 Dynamic CEO of the Year Carlos Mario Giraldo Moreno CEO, Grupo Éxito Visionary Leader of the Year Patricia Menéndez-Cambó Vice Chair, Greenberg Traurig BRAVO Legacy Angel Gurría Secretary General, OECD Lifetime Achievement Horst Paulmann Chairman and Founder, Cencosud 2 CEO of the Year Fernando González CEO, CEMEX 0 Visionary CEO Leadership Andrés Conesa CEO, Aeromexico 1 Visionary CEO Leadership Ed Bastian CEO, Delta Air Lines 7 Dynamic CEO of the Year Maria Fernanda Mejia President, Kellogg Latin America Transformational Leader of the Jorge Pérez Chairman and CEO, Related Group Year Innovative Leader of the Year José Antonio Meade Secretary of Finance and Public Credit, Mexico Lifetime Achievement Ali Moshiri President, Chevron Africa and Latin America Exploration and Production 2 Company CEO of the Year Francisco Garza Egloff CEO, Arca Continental 0 Visionary CEO of the Year Marcos Galperín Founder, President and CEO, Mercado 1 Libre, Inc. Transformational City of the Year City of Medellín Accepted by Mayor of Medellín, Federico 6 Gutiérrez Civic Leader of the Year Eduardo J. Padrón President, Miami Dade College Humanitarian of the Year Patricia -

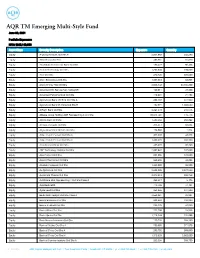

AQR TM Emerging Multi-Style Fund June 30, 2021

AQR TM Emerging Multi-Style Fund June 30, 2021 Portfolio Exposures NAV: $685,149,993 Asset Class Security Description Exposure Quantity Equity A-Living Services Ord Shs H 2,001,965 402,250 Equity Absa Group Ord Shs 492,551 51,820 Equity Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank Ord Shs 180,427 96,468 Equity Accton Technology Ord Shs 1,292,939 109,000 Equity Acer Ord Shs 320,736 305,000 Equity Adani Enterprises Ord Shs 1,397,318 68,895 Equity Adaro Energy Tbk Ord Shs 2,003,142 24,104,200 Equity Advanced Info Service Non-Voting DR 199,011 37,300 Equity Advanced Petrochemical Ord Shs 419,931 21,783 Equity Agricultural Bank of China Ord Shs A 288,187 614,500 Equity Agricultural Bank Of China Ord Shs H 482,574 1,388,000 Equity Al Rajhi Bank Ord Shs 6,291,578 212,576 Equity Alibaba Group Holding ADR Representing 8 Ord Shs 33,044,794 145,713 Equity Alinma Bank Ord Shs 1,480,452 263,892 Equity Ambuja Cements Ord Shs 305,517 66,664 Equity Anglo American Platinum Ord Shs 174,890 1,514 Equity Anhui Conch Cement Ord Shs A 307,028 48,323 Equity Anhui Conch Cement Ord Shs H 1,382,025 260,500 Equity Arab National Bank Ord Shs 485,970 80,290 Equity ASE Technology Holding Ord Shs 2,982,647 742,000 Equity Asia Cement Ord Shs 231,096 127,000 Equity Aspen Pharmacare Ord Shs 565,696 49,833 Equity Asustek Computer Ord Shs 1,320,000 99,000 Equity Au Optronics Ord Shs 2,623,295 3,227,000 Equity Aurobindo Pharma Ord Shs 3,970,513 305,769 Equity Autohome ADS Representing 4 Ord Shs Class A 395,017 6,176 Equity Axis Bank GDR 710,789 14,131 Equity Ayala Land Ord Shs 254,266 344,300 -

Informativo Bursatil

Informativo Bursátil 26 de noviembre de 2020 Año XXIX - Núm 229 • Resumen de Mercado • Resumen de Transacciones de Acciones • Presencia Bursátil de Acciones • Resumen de Transacciones de Cuotas de Fondos • Presencia Bursátil de Cuotas de Fondos • Ofertas de Compra y Venta Vigentes • Valores Extranjeros • Resumen de Transacciones de Renta Fija • Resumen de Transacciones de Intermediación Financiera • Resumen de Operaciones Simultáneas • Operaciones a Plazo Liquidadas Anticipadamente • Operaciones a Plazo Vigentes • Operaciones a Plazo Vigentes por Nemotécnico • Operaciones de Ventas Cortas • Préstamos de Acciones • Operaciones Interbolsas • Hechos Esenciales Bolsa Electrónica de Chile Huérfanos 770, Piso 14, Santiago - Chile. T + 562 - 24840100 / F + 562 - 24840101 / [email protected] / @bolchile / www.bolchile.cl Servicio al Inversionista : 800384100 / Capítulos: 522 - 523 - 147 Informativo bursátil 26 de noviembre de 2020 RESUMEN DE MERCADO PRINCIPALES ALZAS Mercado Negocios Monto ($) Acción Precio ($) Var. (%) Acciones 75 7.989.319.437 ECL 957,03 7.78 Cuotas de Fondos 17 1.524.699.722 AESGENER 137,20 2.05 Valores Extranjeros 0 0 BSANTANDER 34,26 1.81 Renta Fija 2 66.423.757 ANDINA-B 1.698,11 0.19 Intermediación Financiera 3 13.215.233.504 COLO COLO 177,00 0.00 Simultáneas 132 41.036.959.913 Dólar (US$) 1.867 1.019.070.000 ÍNDICES ACCIONARIOS PRINCIPALES BAJAS Variación (%) Acción Precio ($) Var. (%) Índices y sectores Valor Diaria Mensual Anual ENELCHILE 55,93 -3.00 Chile 65 2.313,79 -0.64 15.83 -14.95 COPEC 6.350,00 -2.56 Chileholdings 2.011,19 -0.66 3.59 -10.92 ITAUCORP 2,20 -2.44 Adrian 4.298,25 -0.57 18.50 7.87 FALABELLA 2.700,00 -1.98 Chile large cap 2.103,04 -0.74 17.49 -13.60 CENCOSUD 1.335,00 -1.85 Chile small cap 4.229,70 0.06 5.70 -20.15 Consumo-basico 2.253,89 -0.90 10.22 -20.98 Consumo-discrecional 1.872,28 -1.03 23.28 -12.13 MÁS TRANSADAS Acción Monto ($) Últ.