Community Indicator Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

~ COP11 Performance of Recycled Asphalt G~ DOT/FAA/PM-86/12 -/ Program Engineering Concrete Airport Pavement /.(.L-~ and Maintenance Service Washington, D.C

;~ COP11 Performance of Recycled Asphalt g~ DOT/FAA/PM-86/12 -/ Program Engineering Concrete Airport Pavement /.(.l-~ and Maintenance Service Washington, D.C. 20591 Surfaces G. D. Cline M.C. Hironaka Naval Civil Engineering Laboratory Port Hueneme, CA 93043 Q 24 ~ ~~ ~""" r ~ 01'1• llJ. ... October t 986 Final Report This document is available to the public through the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, Virginia 22161 U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Aviation Administration -----------~--~~ NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its content or use thereof. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT/FAA/PM-86/12 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date PERFORMANCE OF RECYCLED ASPHALT CONCRETE October 1986 AIRPORT PAVEMENT SURFACES 6. Performing Organization Code NCEL (L53) !--:::----...,-,-----------------------------1~~--~~~----~~--~----~ 8. Performing Organization Report No. 7. Authorl s) Technical Note N-1765 Cline, G.D. and Hironaka, M.C. 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAlS) Naval Civil Engineering Laboratory 53-048 Port Hueneme, California 93043-5003 11. Contract ar Grant Na. DTFA01-83-Y-30593 13. Type af Report and Period Covered ~~--------------------~--------------------------------~ 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address U.S. Department of Transportation Final Report Federal Aviation Administration Aug 1983 - May 1986 Program Engineering and Maintenance Service 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20591 APM-740 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract The objective of this research was to make an assessment of the relative performance of recycled versus new asphalt concrete pavement surfaces constructed for airport facilities. -

Rwy 5 Rnav (Gps)

HEMET, CALIFORNIA AL-6678 (FAA) 20254 Rwy Idg APP CRS 4315 TDZE 1513 RNAV (GPS) RWY 5 035° Apt Elev 1515 HEMET-RYAN (HMT) RNP APCH MISSED APPROACH: Climb to 2500 then climbing left turn to T 7900 direct SETER and hold, continue climb-in-hold to 7900. A AWOS-3PT MARCH APP CON UNICOM 118.375 133.5 306.975 123.0(CTAF)L UMIT 25 H N 2931 A S M SETER 2890 M 2704 167 12700 347 ° 4050 2569 ° 7 NM 2689 5188 5000 3876 4106 2238 3000 2673 00 0 5 SW-3, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV 2182 1598 2574 2281 Final approach course offset 14.89°. (MAP) HUMIT (FAF) FOMIN 3343 OTEBE 2.6 NM to HUMIT HUMAN 3 3400 0 0 035° (2.4) 0 4652 3040 3000 ° 4000 2555 3666 035) (IF/IAF) (6 WESIN 5640 SW-3, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV Procedure NA for arrivals at WESIN ELEV TDZE on V186 southeast bound. 1515 1513 23 2500 7900 22 WESIN SETER P P HUMAN U 3% 25 0. X OTEBE 4 FOMIN 2014 2.6 NM to 5 100 X 5500 HUMIT 2.1 NM to 035 4315 ° 3.02° HUMIT H 4000 TCH 40 HUMIT 3400 2520 Rwy 4-22 restricted for 6 NM 2.4 NM 2.7 NM 0.5 NM 2.1 0.5 glider operations. CATEGORY A B C D 1 1 2360-1 2360-14 2360-2 2 LNAV MDA NA 1 1 847 (900-1) 847 (900-14 ) 847 (900-2 2 ) 1 2360-1 2400-14 2600-3 CIRCLING NA 1 MIRL Rwy 5-23 L 845 (900-1) 885 (900-14 ) 1085 (1100-3) HEMET, CALIFORNIA HEMET-RYAN (HMT) Orig-D 10SEP20 33°44'N-117°01'W RNAV (GPS) RWY 5 M1 A ALTERNATE MINS A 21280 INSTRUMENT APPROACH PROCEDURE CHARTS A IFR ALTERNATE AIRPORT MINIMUMS Standard alternate minimums for non-precision approaches and approaches with vertical guidance [NDB, VOR, LOC, TACAN, LDA, SDF, VOR/DME, ASR, RNAV (GPS) or RNAV (RNP)] are 800-2. -

KTNP – Twentynine Palms Airport V1.11 Documentation

KTNP – Twentynine Palms Airport | 29palms.de | 29palms-store.de KTNP – Twentynine Palms Airport v1.11 Documentation 1 | P a g e KTNP – Twentynine Palms Airport | 29palms.de | 29palms-store.de Contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Credits 4 3. General Information 4 4. Technical Information 5 5. Overview 5 6. Scenery Configurator: General 6 7. Scenery Configurator: Troubleshooting 7 8. Copyrights 8 9. Charts 9 1. Introduction Twentynine Palms (formerly known as Twenty-Nine Palms) was named for the palm trees found there in 1852 by Col. Henry Washington. Located in the Mojave Desert, California, dry climate, palm trees, shrubs and sand as far as the eye can see characterize Twentynine Palms Airport and its vicinity. The airport has a Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center nearby which explains occasional military traffic operations at the airport. A video of Marines seizing the airport can be seen here. 2 | P a g e KTNP – Twentynine Palms Airport | 29palms.de | 29palms-store.de Twentynine Palms Airport is the third internal project of our scenery development company 29Palms Scenery Design. Twentynine Palms was actually our first project a few years back. It didn’t reach the final stage of development. But we’ve learned a lot and decided to bring the project back to life which resulted in the release of this scenery. We’ve set a whole new level of detail and realism with the scenery, based on many references from the real airport. It is our first project which comes with animated people and also features many new 3D objects, exclusively designed for this scenery. -

Airport Diagram Airport Diagram

(PSP) ATIS 124.65 121.9 GND CON D 119.7 377.05 128.35 PALM SPRINGS, CALIFORNIA CLNC DEL PALM SPRINGS INTL PALM SPRINGS TOWER 33°50'N E ° 4 AL-545 (FAA) . 11 R VA SW-3, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV 2021 NOV 04 to 2021 OCT 07 SW-3, JANUARY 20200.1° W ANNUAL RATE OF CHANGE BCN GENERAL AVIATION PARKING HS 3 FBO HANGARS HS 1 ELEV HANGAR 449 E E E 13 J R B F D 132.0° H 4952 X 75 0.8% UP 312. 20086 0° L 31 HS 1 AIRPORT DIAGRAM H ELEV A D 407 C C C C C C HS 4 J H HS 2 K B 13 L 132.0° 10000 X 150 C1 312.0° R L 33°49'N 1.0% DOW N 31 ELEV L 0.7% UP H W 398 K 1 A J B G W W 2 3 W W X (PSP) W X W B X G FIELD ELEV 476 HANGARS TWR 583 A1 PALM SPRINGS, CALIFORNIA 116°30'W FIRE PALM SPRINGS INTL STATION FBO TERMINAL SW-3, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV 2021 HANGARS GENERAL AVIATION U.S. CUSTOMS PARKING RWY 13R/31L PCN 64 F/B/W/T RWY 13L-31R PCN 5 F/B/W/T READBACK OF ALL RUNWAY HOLDING INSTRUCTIONS IS REQUIRED. CAUTION: BE ALERT TO RUNWAY CROSSING CLEARANCES. 116°31'W AIRPORT DIAGRAM 20086 SW-3, 07 OCT 2021 to 04 NOV 2021 NOV 04 to 2021 OCT 07 SW-3, CATHEDRAL ONEDEPARTURE (CATH1.PSP) (CATH1.PSP) CATHEDRAL ONEDEPARTURE ATIS 124.65 N MINIMUM CROSSING ALTITUDES T DEPARTURE ROUTE DESCRIPTION GND CON 121.9 FOR PSP VORTAC /R: Climbing left turn heading 100° PALM SPRINGS TOW ER TAKEOFF RUNW AYS 13L V16-370-372: 11600 W 119.7 377.05 DAGGETT to cross PSP VORTAC R-176, then turn left heading 040° to V370: 6200 NE SOCAL DEP CON 113.2 DAG intercept PSP R-104, thence . -

Community Indicator Report

COUNTY OF COUNTY OF BOARD OF SUPERVISORS SAN BERNARDINO BOARD OF SUPERVISORS SAN BERNARDINO Brad Mitzelfelt, Vice Chair ...........................First District Board of Supervisors BradJanice Mitzelfelt Rutherford, Vice ...................................... Chair..........................SecondFirst DisDistricttrict Board of Supervisors JaniceNeil Derry Rutherford ..........................................................................................SecondThird DistrictDistrict County Government Center NeilGary Derry C. Ovitt................................ ..................................................................FourthThird DistrictDistrict 385County North Government Arrowhead CenterAvenue GaryJosie C.Gonzales, Ovitt................................ Chair ................................................. FourthFifth DistrictDistrict San385 Bernardino, North Arrowhead CA 92415-0110 Avenue Josie Gonzales, Chair ....................................Fifth District GREGORY C. DEVEREAUX San Bernardino,(909) 387-4811 CA 92415-0110 Laura H. Welch Clerk of the Board of Supervisors GREGORYChief Executive C. DEVEREAUX Officer (909) 387-4811 Laura H. Welch Chief Executive Officer Clerk of the Board of Supervisors Welcome to the 2012 edition of the San Bernardino County Community Indicators WelcomeReport. As chairpersons for this important countywide effort, it is our pleasure to to the 2012 edition of the San Bernardino County Community Indicators Report. once again present this research and analysis that reflects key indicators of -

Program Overview and Updates

Office of Technical Services and Programs Caltrans Division of Aeronautics Program Overview and Updates Sept 14, 2018 Association of California Airports Conference Lake Tahoe, CA Program Overview and Updates Grants and Loan Program State Capital Improvement Plan California Airport Pavement Management System California Aid to Airports Program (CAAP) Annual Credits: $10,000/year to GA airports ($1.49 million) – 100% State funded grant Airport Improvement Program (AIP) Matching Grants– Up to 5% of an FAA AIP Grant* Acquisition and Development (A&D) Grants – 90% State funded safety, pavement preservation projects, and Airport Land Use Compatibility Plan projects (requires a 10% local match)* * Construction cannot start prior to grant approval AIP Match Funding • FY 2016-17 - $1.4M awarded to 48 projects • FY 2017-18 - $1.1M awarded to 28 projects • FY 2018-19 - $1.4M Capacity (grant cap maximum set at $50K) A&D Funding • FY 2016-17 - $1.1M awarded toward 4 projects • FY 2017-18 - $0 capacity ($2.4 M programmed) • FY 2018-19 - $0 capacity ($2 M programmed) Airport Loan Program Low interest loans for eligible publicly owned/public use airports* Current rate ~3.9% APR; 17-Year payback – Revenue generating projects (e.g. hangar construction and aviation fuel facilities) to benefit GA – AIP Local Match (10%) Grant eligible projects – Acquisition and Development Grant eligible projects *Excludes projects that accommodate scheduled air carriers 5 Airport Loan Program Status Airport Loan Account Balance: $31 Million In FY 2017-18, $0.4M -

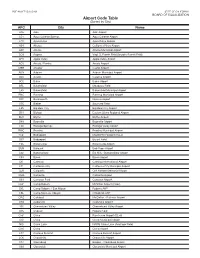

Airport Code Table (Sorted by City)

BOE-810-FTI (S1) (5-10) STATE OF CALIFORNIA BOARD OF EQUALIZATION Airport Code Table (Sorted by City) APC City Name A26 Adin Adin Airport L54 Agua Caliente Springs Agua Caliente Airport L70 Agua Dulce Agua Dulce Airpark A24 Alturas California Pines Airport AAT Alturas Alturas Municipal Airport 2O3 Angwin Virgil O. Parrett Field (Angwin-Parrett Field) APV Apple Valley Apple Valley Airport ACV Arcata / Eureka Arcata Airport MER Atwater Castle Airport AUN Auburn Auburn Municipal Airport AVX Avalon Catalina Airport 0O2 Baker Baker Airport BFL Bakersfield Meadows Field L45 Bakersfield Bakersfield Municipal Airport BNG Banning Banning Municipal Airport O02 Beckwourth Nervino Airport O55 Bieber Southard Field L35 Big Bear City Big Bear City Airport BIH Bishop Eastern Sierra Regional Airport BLH Blythe Blythe Airport D83 Boonville Boonville Airport L08 Borrego Springs Borrego Valley Airport BWC Brawley Brawley Municipal Airport 7C4* Bridgeport MCMWTC Heliport (7CL4) O57 Bridgeport Bryant Field F25 Brownsville Brownsville Airport BUR Burbank Bob Hope Airport L62 Buttonwillow Elk Hills - Buttonwillow Airport C83 Byron Byron Airport CXL Calexico Calexico International Airport L71 California City California City Municipal Airport CLR Calipatria Cliff Hatfield Memorial Airport CMA Camarillo Camarillo Airport O61 Cameron Park Cameron Airpark C62* Camp Roberts McMillan Airport (CA62) SYL Camp Roberts / San Miguel Roberts AHP CSL Camp San Luis Obispo O’Sullivan AHP CRQ Carlsbad McClellan - Palomar Airport O59 Cedarville Cedarville Airport 49X Chemehuevi -

2020-21 Adopted Budget Contents

2020–2021 ADOPTED BUDGET THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK ® GOVERNMENT FINANCE OFFICERS ASSOCIATION Distinguished Budget Presentation Award PRESENTED TO San Bernardino County California For the Fiscal Year Beginning July 1, 2019 Executive Director Government Finance Officers Association of the United States and Canada (GFOA) presented a Distinguished Budget Presentation Award to San Bernardino County, California, for its Annual Budget for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 2019. In order to receive this award, a governmental unit must publish a budget document that meets program criteria as a policy document, as a financial plan, as an operations guide, and as a communications device. This award is valid for a period of one year only. We believe our current budget continues to conform to program requirements, and we are submitting it to GFOA to determine its eligibility for another award. THIS PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK Contents Published – December 2020 Executive Summary Message from the Chief Executive Officer ................................................... i County Profile .............................................................................................. 1 County Budget Overview ............................................................................. 6 Long-Term Debt ........................................................................................ 12 Summary of Related Laws, Policies and Procedures ................................ 22 Analysis of Budgets Administration Board of Supervisors ................................................................................ -

Fiscal Year 2004 Omnibus Appropriations and California Implications - December 2003

THE CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE FOR FEDERAL POLICY RESEARCH 419 New Jersey Avenue, SE, Washington, D.C. 20003 202-546-3700 Fax: 202-546-2390 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.calinst.org SPECIAL REPORT: Fiscal Year 2004 Omnibus Appropriations and California Implications - December 2003 CONTENTS: On November 25, 2003, House and Senate Conferees combined seven DEPARTMENT OF unfinished appropriations bill into the 2004 Omnibus Consolidated Appropriations AGRICULTURE ........1 Act, HR 2673 (H-Rept. 108-401). The bDecember 8, 2003 details a total of $820 billion in FY04 funding, although only $328 billion is subject to the discretion of DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Congress (the nearly $500 billion remainder represents mandatory spending). .......................3 The measure also requires a 0.59 percent across-the-board cut (not accounted DEPARTMENT OF for in the funding amounts included in the Omnibus or recounted here) for all 2004 COMMERCE ...........6 funds. Not only is the 0.59 percent reduction applied to every line item in this bill, DEPARTMENT OF STATE ..7 but it also applies to previously enacted non-defense bills (Energy & Water, Homeland Security, Interior, and Leg. Branch). Further, all Commerce-Justice- DEPARTMENT OF LABOR ..7 State appropriations accounts are subject to an additional 0.46 percent reduction DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH on top of the 0.59 percent across-the-board cut. AND HUMAN SERVICES The following is a quick analysis of the Omnibus Appropriations from a .......................7 California perspective, prepared by the California Institute. We apologize for DEPARTMENT OF errors or omissions in our discussion, and would appreciate any input or feedback EDUCATION ...........9 on how to make improvements. -

San Bernardino County Community Indicators Report 2014

This report was produced by The Community Foundation for the benefit of San Bernardino County. COUNTY OF SAN BERNARDINO BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Robert A. Lovingood ....................................First District Board of Supervisors Janice Rutherford, Chair ........................... Second District James Ramos ................................................ Third District County Government Center Gary C. Ovitt, Vice Chair...........................Fourth District 385 North Arrowhead Avenue Josie Gonzales ...............................................Fifth District San Bernardino, CA 92415-0110 GREGORY C. DEVEREAUX (909) 387-4811 Laura H. Welch Clerk of the Board of Supervisors Chief Executive Officer Building and maintaining a healthy, vibrant, and livable community demands honest and repeated self-assessment. It requires constantly measuring the progress we are making toward the realization of our shared Countywide Vision. That is the purpose of the annual San Bernardino County Community Indicators Report. This 2014 report marks our fifth consecutive year of taking a hard look at our incredibly large and amazingly diverse county through the prisms of our economy, schools, healthcare, public safety, environment, and our overall quality of life. These are the interrelated and interdependent elements of the “complete county” our residents and investors want our community to become through the Vision process. The idea behind making this report an annual effort was to measure our performance and detect trends so that the community could assess and refine its efforts toward achieving the Countywide Vision. After five years, we can begin to see the progress we are making and where more work needs to be done. The good news is that the county’s foreclosure rate has dropped from 5 percent to 1 percent and the high school dropout rate has declined by 30 percent. -

Where Are Laanc Facilities in My Area?

WHERE ARE LAANC FACILITIES IN MY AREA? Updated with LAANC Expansion Facilities! December 2019 Houston Air Route Traffic Control Center (ZHU) Brownsville/South Padre Island International Airport (BRO), Mobile Regional Airport (MOB), Salina Regional Airport (SLN), South Central Brownsville, TX Mobile, AL Salina, KS Easterwood Field (CLL), Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport (BTR), Philip Billard Municipal Airport (TOP), College Station, TX Baton Rouge, LA Topeka, KS Conroe-North Houston Regional Airport (CXO), Lafayette Regional Airport (LFT), Mount Vernon Airport (MVN), Houston, TX Lafayette, LA Mt Vernon, IL Scholes International At Galveston Airport (GLS), Austin–Bergstrom International Airport (AUS), Quincy Regional Airport (UIN), Galveston, TX Austin, TX Quincy, IL Georgetown Municipal Airport (GTU), Corpus Christi International Airport (CRP), Chanute Martin Johnson Airport (CNU), Georgetown, TX Corpus Christi, TX Chanute, KS Valley International Airport (HRL), Aransas County Airport (RKP), Dodge City Regional Airport (DDC), Harlingen, TX Rockport, TX Dodge City, KS San Marcos Regional Airport (HYI), San Antonio International Airport (SAT), Emporia Municipal Airport (EMP), Austin, TX San Antonio, TX Emporia, KS Laredo International Airport (LRD), Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport (MSY), Hays Regional Airport (HYS), Laredo, TX Kenner, LA St, Hays, KS McAllen Miller International Airport (MFE), William P. Hobby Airport (HOU), Lawrence Municipal Airport (LWC), McAllen, TX Houston, TX Lawrence, KS Sugar Land Regional Airport -

HR401-Xxx.Ps

915 CONFERENCE TOTAL—WITH COMPARISONS The total new budget (obligational) authority for the fiscal year 2004 recommended by the Committee of Conference, with compari- sons to the fiscal year 2003 amount, the 2004 budget estimates, and the House and Senate bills for 2004 follow: [In thousands of dollars] New budget (obligational) authority, fiscal year 2003 ........................ $430,990,470 Budget estimates of new (obligational) authority, fiscal year 2004 469,697,348 House bill, fiscal year 2004 ................................................................... 478,406,936 Senate bill, fiscal year 2004 .................................................................. 473,552,979 Conference agreement, fiscal year 2004 .............................................. 480,345,954 Conference agreement compared with: New budget (obligational) authority, fiscal year 2003 ................ +49,355,484 Budget estimates of new (obligational) authority, fiscal year 2004 .............................................................................................. +10,648,606 House bill, fiscal year 2004 ............................................................ +1,939,018 Senate bill, fiscal year 2004 ........................................................... +6,792,975 DIVISION F—DEPARTMENTS OF TRANSPORTATION AND TREASURY, AND INDEPENDENT AGENCIES APPROPRIA- TIONS ACT, 2004 CONGRESSIONAL DIRECTIVES The conferees agree that Executive Branch propensities cannot substitute for Congress’s own statements concerning the best evi- dence of Congressional