LUXURY for the MASSES: WHY WE CAN't ALL HAVE IT ALL By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010/11 Edition 100

Online Fashion 2010/11 edition 100 the people behind British fashion websites BY LEON BAILEY-GREEN FEATURING BRENT HOBERMAN, HILARY ALEXANDER, KATE RUSSELL & DENIZE HEWITT Online Fashion 100 2010/11 About Online Fashion 100 2010/11... “It is estimated that Britons will spend £4.27bn* on fashion online this year, but who are the people behind our fashion website businesses? You’re about to find out who they are, what they do and how they impact the industry. Online Fashion 100 is your guide to the buyers, bloggers, directors, entrepreneurs, editors, investors, politicians and even celebrities that influence the business of online fashion. As the founder of The Online Fashion Agency, a fashion website communications company, it is noticeable how much the fashion sector of the UK’s digital economy is evolving. Whether you’re a consumer, eager to become savvy LEON BAILEY-GREEN to the workings behind the online fashion scenes, or an online fashion professional, interested WWW.LEONBAILEYGREEN.COM in learning about others in the industry, I’m @LEONBAILEYGREEN sure you’ll find Online Fashion 100 useful. [email protected] THE ONLINE FASHION AGENCY To keep up with industry developments sign up for WWW.THEONLINEFASHIONAGENCY.COM email updates at The Online Fashion Agency @THEONLINEFASH and visit LEON BAILEY-GREEN regularly to rate [email protected] British websites and the people behind them. I would like to thank Brent Hoberman, Hilary Alexander, Kate Russell and Denize Hewitt for their input into Online Fashion 100 2010/11. You’ll find the list is in alphabetical order by surname, plus, a very special entrant closing at number 100. -

Fashion Galore, India’S Premium Fashion & Lifestyle Platform

Tuesday, July 31, 2012 THE GRAND, NEW DELHI SHOWCASING THE HOTTEST LIFESTYLE TRENDS IN: Designer Homes, Furnishings, Home Décor, Travel, Wellness, Apparel, Jewellery, Beauty, Watches, Gadgets & Hot Wheels Who are we ? We are Fashion Galore, India’s Premium Fashion & Lifestyle Platform. Fashion Galore, a combination platform (B2B & B2C) is an initiative by Exotic Multimedia, a media and lifestyle conglomerate with 3 verticals on-board :- • Events (Fashion Galore, Bridal Fashion Fair) • Brand Management (FTV Yacht, DLF IPL) • Publishing (fashioncurry.com) Objective “To offer participating Lifestyle Brands a holistic opportunity to showcase their products, engage the potential consumer in the experiential workshops and help them develop on-the-spot bookings” Target Audience Statistics CATEGORY NAMES AGE INCOME GROUP BRACKET 200 High Net-worth Burmans, Ruias, Sahnis, 30+ 2cr+ (annual) Individuals from Top Goenkas, Mittals etc Business Families 200 Top Corporate BMR,Consulting Firms, 30+ 1000cr+ (annual) Houses American Express, Grant Thornton,Audi, Jot Impex, BMW, Nissan, Natuzzi, BNP Paribas, Samsung etc 200 Prominent Ramola Bachchan, Tanisha 30+ 60lakh+ (annual) Personalities Mohan, Vandana Vadehra, Rajan Madhu, Vandana Luthra etc.), 200 Style Connoisseur Ridhhima Kapoor Sahni, 30+ 1cr+ (annual) Naveen Ansal, Gurinder Sahni, Peter Punj etc. 200 Seasoned P3Ps Feroze Gujral, Ala Madhu, 30+ 60lakh+ (annual) Rashmi Virmani, Vandana Singh etc Market Segmentation DELHI & NCR PUNJAB (Chandigarh & Ludhiana) RAJASTHAN(Jaipur) MP (Bhopal, Gwalior, -

Nature's Remedy

DIAne STARTInG GUn vOn GOLDen GLOBe nOmInATIOnS FURSTenBeRG WeRe ReveALeD THURSDAY — PRe-FALL, AnD THe HOLLYWOOD PAGe 12 ReD cARPeT FASHIOn RAce BeGAn. PAGe 11 WFRIDAY, DECEMBER 16,W 2011 ■ $3.00 ■ WoMEn’sD WEAR DAIlY Nat u re’s Remedy This winter, Aveda and Ojon are aiming to provide natural solutions for hair issues that have traditionally required heavy chemicals: Aveda, with its Invati line for thinning hair, and Ojon, with Super Sleek, a collection designed to deliver smooth hair without chemicals like formaldehyde. Both collections bow next month. For more, see page 6. PHOTO BY THOmAS IAnnAccOne in WWD ToDaY Kors Goes Ka-ChinG Ralph Lauren names Lalonde PAGE 2 NEWS: Ralph Lauren Corp. named former LVMH executive Daniel Lalonde head of its international operations. s Designer’s Shares Leap Beauty Sales Strong for Holiday PAGE 6 BEAUTY: While stores’ performance has been patchy, retailers expect to see growth in their On Wall Street Debut beauty sales at holiday, driven by celebrity were traded. given the more than 190 million fragrances. By lIsA loCkWooD shares outstanding, the closing price left kors with a market capitalization of $3.82 billion. Proenza Schouler Said Opening Store PAGE 12 “I’M FEElIng gREAt, ” said an exuberant, After the stock was priced, a press-wary FASHION SCOOP: The designers are said to be and newly flush Michael kors, after ring- Idol whisked kors and the team away, saying eyeing a spot on Madison Avenue for their first ing the opening bell of the new York stock securities and Exchange Commission rules freestanding store. -

Tesis María Mondéjar 34806861H Neologismos En El Discurso Sobre Moda En La Prensa Femenina.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA ESCUELA INTERNACIONAL DE DOCTORADO Neologismos en el discurso sobre moda en la prensa femenina Dª. María Dolores Mondéjar Fuster 2019 UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA FACULTAD DE LETRAS Neologismos en el discurso sobre moda en la prensa femenina Tesis doctoral presentada por Dª. María Dolores Mondéjar Fuster, dirigida por la Dra. Dª. Carmen Sánchez Manzanares, para optar al Grado de Doctora. Murcia, 2019 A mis padres. Por todo. AGRADECIMIENTOS En primer lugar, me gustaría comenzar los agradecimientos dedicando este trabajo a mis padres. Ellos han sido las personas que a lo largo de mi vida más me han ayudado y acompañado en mis mejores y peores momentos. A ellos va dedicada esta tesis por su comprensión, infinita generosidad, amor y apoyo incondicional. En segundo lugar, me gustaría reconocer y agradecer enormemente la labor de la profesora Dra. Carmen Sánchez Manzanares, directora de esta investigación. Ella siempre me ha orientado, ha contestado mis dudas con amabilidad y profesionalidad y me ha guiado a lo largo del proceso desde el primer proyecto de esta investigación. Además, me introdujo en el apasionante mundo de la neología, del cual todavía me considero una neófita, a través de mi participación en el grupo de investigación de neología de la Universidad de Murcia, integrado en el Observatorio de Neología de la Universidad Pompeu Fabra (OBNEO), y de mi colaboración en el Diccionario de Neologismos del Español Actual, NEOMA (2016). Por otra parte, quiero dar las gracias a otra de las personas que han hecho que este trabajo llegue a su fin, Kevin Power. Sin ninguna duda su incansable entusiasmo, afabilidad, vitalidad, aliento, tesón y positividad han impregnado la última fase de esta tesis. -

A Study on the Red Carpet Dress of Film Festivals in the Great China Region

J. fash. bus. Vol. 18, No. 3:148-166, Jul. 2014 ISSN 1229-3350(Print) http://dx.doi.org/10.12940/jfb.2014.18.3.148 ISSN 2288-1867(Online) A Study on the Red Carpet Dress of Film Festivals in the Great China Region Wang Ling · Lee Misuk⁺ Dept. of Clothing and Textiles, Chonnam National University Dept. of Clothing and Textiles, Chonnam National University, Human Ecology Research Institute, Chonnam National University Abstract The purpose of this study is to establish the basic materials necessary for red carpet fashion design by examining the formativeness and fashion images of red carpet dresses at film festivals in the Great China Region. For the purpose of this study, research methods include a literature review on the origin and significance of red carpet dresses, the characteristics of film festivals in the Great China Region and their red carpet dresses as well as an analysis of the formative features and images of 615 red carpet dresses collected from each film festival official homepage, diverse media articles, and online search sites (www.google.com, www.hao123.com). The research finding can be summarized as follows: First, the formative features of red carpet dress designs were analyzed herein. It was found that the most frequently appearing type of silhouette was straight followed by hourglass and bulk in order. More specifically these included fit and flare, mermaid, trapeze, and slim in order. For the neckline styles, strapless was the most frequently seen followed by camisole, jewel, and one shoulder. Solid colors were more often seen than multiple colors. -

Neonyt Gets Ready for Take-Off at Tempelhof Airport

Press Release 13 January 2020 Neonyt gets ready for take-off at Tempelhof Lilliffer Seiler Tel. +49 69 75 75-6738 airport [email protected] www.messefrankfurt.com www.neonyt.com With more than 210 sustainable fashion labels, exclusive product launches, an accompanying line-up of over 50 events, a sensational fashion show and numerous new partners, Neonyt is opening its doors for the first time at Tempelhof Airport tomorrow. More space, more brands, an even bigger line-up: During Berlin Fashion Week from 14-16 January 2020, Neonyt, taking place at the now decommissioned Tempelhof Airport, is once again raising the bar when it comes to sustainability and innovation in fashion. With more than 210 sustainable fashion brands from 22 countries, this edition of Neonyt has the highest number of exhibitors yet and is even more international. And in keynotes, discussion panels and masterclasses, an extensive line-up of accompanying events will be shedding light on the most important sustainability and innovation topics, as well as providing answers and facts about the future of fashion. Messe Frankfurt Exhibition GmbH Green Carpet Collection: Lanius will be launching sustainable red carpet fashion at Neonyt / Source: : Ludwig-Erhard-Anlage 1 Lanius 60327 Frankfurt am Main “With a multifaceted and interdisciplinary line-up of side events and selected Showcases, Neonyt, as a real hub for retailers, is once again encouraging people to take action for more sustainability in fashion,” says Olaf Schmidt, Vice President of Textiles and Textile Technologies at Messe Frankfurt. “Neonyt sees sustainability not just as a mere fashion trend, but as a complete innovation process for the entire industry.” One hangar, one hall – A huge selection of sustainable fashion For three days, Berlin Fashion Week visitors can also look forward to discovering sustainable streetwear and casualwear, high fashion and accessories such as shoes, bags, jewellery and home textiles in Hangar 4 and Hall X. -

Working Towards Sustainable Fashion

La revue officielle des fonctionnaires Internationaux – The official magazine of international civil servants © DAMIANO ANDREOTTI / COLLECTION CITTADELLARTE / FONDAZIONE PISTOLETTO WORKING TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE JULY-AUGUST 2020 JULY-AUGUST / FASHION JUILLET-AOÛT Interview with UNDP Retour au Palais Que faire à Genève 801 # Goodwill Ambassador des Nations après cet été ? Michelle Yeoh le déconfinement University of Geneva Discover our programs dedicated to International & Non-Governmental Organizations Discover the wide range of GSEM Executive Education programs from business-oriented to non-profit organizations that will help develop your management skills. Our non-profit programs are designed for professionals in IOs, NGOs, NPOs or Social Enterprise in managerial positions as well as professionals from the private sector looking for a career shift. DAS Effective Leadership of IOs DAS Gestion et management dans les organismes sans but lucratif (OSBL) • Master advanced management skills and practices applicable • Maîtriser, innover et mener des projets dans un to intergovernmental, public, and non-profit organizations domaine en évolution • Strengthen your skills in leadership, communication, and • Comprendre et analyser les enjeux et défis des OSBL team management • Comprendre et maîtriser les principales problématiques • Access an extensive network of professionals and build comptables, budgétaires, financières et fiscales strategic connections in a competitive international • Savoir communiquer, développer des capacités environment de -

Medpoint Fashion Show Profile

ALWAYS IN THE MIDDLE Shaikha Noora Bint Khalifa A.Aziz Al Kalifa Chairwomen & CEO Medpoint Design & Event Management Shaikha Noora Bint Khalifa AlKhalifa is the CEO & Chairwomen of Medpoint Design, a leading design company based in Kingdom of Bahrain. H.E. holds a Bachelor Degree in Mass Communication from New York University and Masters in Mass Communication & Public Relation from Ahlia University. Along with, she was awarded with "Emerging Women CEO of the year" twice in a row in 2014 & 2015. Group of Companies Her Royal Highness Princess Sabeeka bint Ibrahim Al Khalifa. Hongrin An award for the "Young Bahraini Entrepreneurs" from Supreme Council of Women (SCW)'s President to Shiakha Noora Bint Khalifa Al Khalifa Nada Alshomali Managing Director for Women and Fahion Event (Public Event Section) Nada AlShomeli Managing Director of Women & Fashion Events Department, she established her first Department store in Moda Mall which is one of the most luxurious malls in our Kingdom and home to the largest portfolio of high-end brands. Therefore, she has expanded to work with Medpoint Design in order to be closer to the designers and promote them locally and internationally. WHO WE ARE Medpoint Design & Event Management Company was founded in 2008 which specializes in advertising, media activities, and hosting highly beneficial Seminars by International Speakers and Authors of great repute. Our main focus of attention is on Women Exhibitions, Workshops, Fashion shows, Seminars and Events that helps them to develop their businesses and to provide them the opportunity to take their work to the next level. Medpoint strives to exceed the expectation of its clients by bringing together concepts and hosting prestigious events that educate and entertain its clients while promoting and supporting the Kingdom of Bahrain. -

The-Knockoff-Economy-Excerpt-Raustiala-Sprigman.Pdf

THE KNOCKOFF ECONOMY HOW IMITATION SPARKS INNOVATION KAL RAUSTIALA AND CHRISTOPHER JON SPRIGMAN 3 RAUSTIALA-titlepage-Revised Proof iii June 1, 2012 9:11 PM Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2012 by Kal Raustiala and Christopher Jon Sprigman Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. CIP to come ISBN-13: 9780195399783 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper RAUSTIALA-copyright-Revised Proof iv May 31, 2012 5:48 AM THE KNOCKOFF ECONOMY RAUSTIALA-halftitle2-Revised Proof 1 June 1, 2012 9:11 PM INTRODUCTION Every spring, millions of viewers around the world tune in to watch the Academy Awards. Ostensibly, the Oscars are about recognizing the year’s best movies. But for many people the Oscars are really about fashion. Fans and paparazzi press against the rope line to see Hollywood stars pose on the red carpet in expensive designer gowns. -

Surprise and Seduction: Theorising Fashion Via the Sociology of Wit Dita

Surprise and seduction: Theorising fashion via the sociology of wit Dita Svelte A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social Sciences Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences UNSW Sydney 12 September 2019 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: SVELTE First name: DITA Other name/s: ISHTAR ARTEMIS Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) School: School of Social Sciences Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: Surprise and seduction: Theorising fashion via the sociology of wit Abstract 350 words maximum: What insights might a sociology of wit as applied to the phenomenon of fashion generate? This thesis applies the sociology of humour to fashion to develop a concept of wit that contributes to further understanding fashion. The thesis argues that this concept of wit is characterised by qualities of surprise and seduction. Surprise is defined as the experience of an unexpected, creative intellectual insight expressed in a pithy manner; seduction is the experience of being led astray, and also the desire of the subject to be led astray. The thesis demonstrates the presence of empirical sites of wit within fashion in the form of the dandy and glamour. It utilises Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus [2000] (1836) to further conceptualise the wit of fashion at the intersection of theories of humour and theories of fashion. The contribution of the wit of fashion to classical texts in the sociology of fashion -

The Oscars Red Carpet Pre-Show

Networking Knowledge 7(4) All About Oscar An Educational and Inspirational Broadcast: The Oscars Red Carpet Pre-Show LUKASZ SWIATEK, The University of Sydney ABSTRACT The annual Academy Awards pre-show, currently titled The Oscars: Red Carpet Live, has become an integral part of Hollywood’s ‘night of nights’. Produced by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the show captures a media event or media spectacle that has strong commercial imperatives. The pre-show is often perceived to be nothing more than an insipid commentary about stars, their personal lives and, of course, the clothes that they wear on Oscar night. However, this article argues that the pre-show is much more informative and richer than simplistic criticisms suggest. Specifically, the broadcast educates viewers about filmmaking and the field of cinema, as well as social norms and customs, presenting behaviours and attitudes that are considered to be acceptable and unacceptable. A detailed analysis of the 2013 show confirms this argument; it also finds that parts of the broadcast are inspirational – intentionally and unintentionally so – providing viewers with motivational stories and stimulating ideas. KEYWORDS Academy Awards; Oscars; red carpet; fashion; film industry; education; inspiration; marketing; media spectacle; media event 1 Networking Knowledge 7(4) All About Oscar Introduction The Oscars red carpet pre-show is eagerly anticipated and attentively watched each year by millions of viewers around the world. Red carpet moments are often unforgettable, as Bronwyn Cosgrave (2007, vii) reminds us: ‘Oscars after Oscars, since the ceremony’s inception in 1929, it is a red-carpet look memorably modelled by an actress great that’s proved the preeminent showstopper, consistently upstaging other definitive aspects of the ceremony from the opening monologue to the speeches’. -

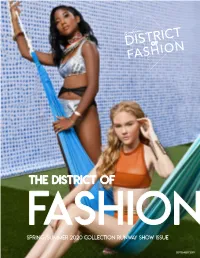

Spring/Summer 2020 Collection Runway Show Issue

SPRING/SUMMER 2020 COLLECTION RUNWAY SHOW ISSUE SEPTEMBER 2019 DISTRICT OF FASHION SS20 3 Q&A WITH NEIL ALBERT Q: HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT THE SUCCESS OF THE DISTRICT OF FASHION RUNWAY SHOW THUS FAR? District of Fashion has been a huge success. From its initial launch and show in September 2018 which had around 400 attendees, to its most recent event at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, which had over 600 attendees, and the September 2019 event, where over 1,100 people asked to be put on the list, it shows the growth of the event and the popularity of the event. It, of course, displays how hard [Creative Directors] Remi and Roquois have worked, as well as their partners—the DC government, OCTFME, 202Creates and the Mayor’s Commission on Fashion Arts & Events. Q: WHAT ARE YOUR THOUGHTS ON THE DISTRICT Q: WHAT ABOUT THE FUTURE OF FASHION IN DC? OF FASHION? WHERE DO YOU THINK WE ARE HEADED? The District of Fashion has become the premier I think District of Fashion has catalyzed the runway event in the District of Columbia. The event fashion industry in DC and the future is bright. and concept have only been around for a year, but In the region, the country, and hopefully around its popularity has grown exponentially during that the world, people will see DC as a fashion capital, time. The popularity is not just recognized by the much like Paris and Milan. Hopefully, we’ll begin attendees, but the fashion industry in the DC area to see the inclusion and participation of higher has been paying attention.