Barnard College Joan Rivers and the Spectacle Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cougar Town S02 Vostfr

Cougar town s02 vostfr click here to download Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Cougar Town S06E09 VOSTFR HDTV Cpasbien permet de télécharger des torrents de films, séries, musique, logiciels et jeux. Accès direct à torrents . Chicago Fire S03E02 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 5, 0. Castle S07E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Mo, 1, 1. Chicago Fire Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 13, 8. Chicago Fire Saison Cougar Town S05E13 FINAL FRENCH HDTV, Mo, 2, 0. Charmed Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 10, 5 Chicago PD Saison 1 VOSTFR HDTV, Go, 2, 2 Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, Go, 4, 2. 24 Heures Chrono - Saison 2 Beverly Hills Nouvelle Génération - Saison 2 A Young Doctor's Notebook - Saison 2 .. Cougar Town - Saison 2. www.doorway.ru season 2 p — omcougar-town-seasonepisode-2 Hosts: Filenuke Movreel Sharerepo www.doorway.ruS04Ep. cougar town s05e09 p-mifydu's blog. www.doorway.rulm. www.doorway.ruilm. www.doorway.rup. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.ru, MB. Cougar Town/Cougar Town_S01/www.doorway.rulm. Routine Her Amazed, Thing in dallas vostfr s02 Little Mansion was my first Sue s02 Dallas vostfr s02 href="www.doorway.ru Season 1, Season 2, Season 3, Season 4. Release Year: In Season 1, Detective Gordon tangles with unsavory crooks and supervillains in Gotham City . Cougar Town Saison 1 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 66, Cougar Town Saison 2 FRENCH HDTV, GB, 51, 6. Cougar Town S03E01 VOSTFR HDTV, Saison 2 · Liste des épisodes · modifier · Consultez la documentation du modèle. -

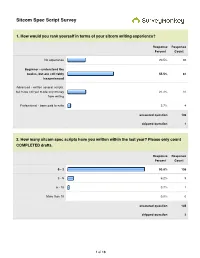

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

2010/11 Edition 100

Online Fashion 2010/11 edition 100 the people behind British fashion websites BY LEON BAILEY-GREEN FEATURING BRENT HOBERMAN, HILARY ALEXANDER, KATE RUSSELL & DENIZE HEWITT Online Fashion 100 2010/11 About Online Fashion 100 2010/11... “It is estimated that Britons will spend £4.27bn* on fashion online this year, but who are the people behind our fashion website businesses? You’re about to find out who they are, what they do and how they impact the industry. Online Fashion 100 is your guide to the buyers, bloggers, directors, entrepreneurs, editors, investors, politicians and even celebrities that influence the business of online fashion. As the founder of The Online Fashion Agency, a fashion website communications company, it is noticeable how much the fashion sector of the UK’s digital economy is evolving. Whether you’re a consumer, eager to become savvy LEON BAILEY-GREEN to the workings behind the online fashion scenes, or an online fashion professional, interested WWW.LEONBAILEYGREEN.COM in learning about others in the industry, I’m @LEONBAILEYGREEN sure you’ll find Online Fashion 100 useful. [email protected] THE ONLINE FASHION AGENCY To keep up with industry developments sign up for WWW.THEONLINEFASHIONAGENCY.COM email updates at The Online Fashion Agency @THEONLINEFASH and visit LEON BAILEY-GREEN regularly to rate [email protected] British websites and the people behind them. I would like to thank Brent Hoberman, Hilary Alexander, Kate Russell and Denize Hewitt for their input into Online Fashion 100 2010/11. You’ll find the list is in alphabetical order by surname, plus, a very special entrant closing at number 100. -

TV Listings Aug21-28

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 21, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Stand Up to Cancer (N) NCIS: New Orleans ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Retire NCIS ’ NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ Grace Paid Prog. ThisMinute 5 5Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ 1st Look In Touch Hollywood 6 6Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle ’ Paid Prog. 9 9MLS Soccer Chicago Fire FC at Orlando City SC. Weekend News WGN News GN Sports Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Lawrence Welk’s TV Great Performances ’ This Land Is Your Land (My Music) Bee Gees: One Night Only ’ Agatha and Murders 11 Father Brown ’ Shakespeare Death in Paradise ’ Professor T Unforgotten Rick Steves: The Alps ’ 12 12 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Skin Care 24 24 High School Football Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 WNBA Basketball: Lynx at Sky Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ News Flannery Game of Talents ’ Bensinger TMZ (N) ’ PiYo Wor. -

Ändring V 37 I Kanal 5

2017-08-31 14:30 CEST Ändring v 37 i Kanal 5 31 augusti 2017 ÄNDRING I KANAL 5 Vecka 37 2017 Fredag 15 september utgår Collateral kl 22.00 och ersätts av Poseidon. Cougar Town är nyinsatt kl 05.35. Tablån ska se ut enligt nedan. 22.00Poseidon Det är nyårsafton och festligheterna har börjat ombord på lyxkryssaren Poseidon i norra Atlanten. Fartygets gäster samlas för att fira det nya året i den magnifika danssalongen. Men en monstervåg är på väg rakt emot dem. Vågen kastar fartyget våldsamt åt babord innan det kantrar och rullar runt med kölen uppåt. Passagerare och besättning krossas eller sugs ut i havet när vattnet rusar in. Kvar finns ett par hundra överlevande som kämpar för sina liv tills räddningen kommer. Skådespelare: Kurt Russell, Josh Lucas, Emmy Rossum, Richard Dreyfuss, Jacinda Barrett. Regi: Wolfgang Petersen. Amerikansk äventyrsfilm från 2006. Åldersgräns: 15 år. Originaltitel: Poseidon. 23.50Vehicle 19 01.25izombie 02.25Criminal Minds 03.10Breaking News med Filip & Fredrik 04.00Breaking News med Filip & Fredrik 04.50Gilmore Girls 05.35-06.00Cougar Town I detta avsnitt: Jules och Grayson försöker ha gemensam ekonomi men inser att de båda måste göra uppoffringar om de faktiskt vill gifta sig - och det kommer inte att bli lätt. Lauries Krazy Kakes-företag går förvånansvärt bra och Travis övertalar henne att ta några vuxensbeslut på egen hand. Jules är en heltidsarbetande tonårsmamma som inser att livet inte behöver vara slut vid 40. Sonen Travis är inte helt glad över hennes ambitioner att träffa en ny man och väninnan Ellie drar sig inte för att kläcka en och annan sarkastisk kommentar om Jules nya livsstil. -

![Agnes Scott Alumnae Magazine [1984-1985]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4602/agnes-scott-alumnae-magazine-1984-1985-434602.webp)

Agnes Scott Alumnae Magazine [1984-1985]

iNAE m^azin: "^ #n?^ Is There Life After CoUege? AGNES SCOTT COLLEGE ALUMNAE MAGAZINE v^ %' >^*^, n^ Front Coilt; Dean julia T. Gars don her academic robe for one of the last times before she ends her 27-year ten- ure at ASC. (See page 6.) COVER PHOTO by Julie Cuhvell EDITORIAL STAFF EDITOR Sara A. Fountain ASSOCIATE EDITOR Juliette Haq3er 77 ASSISTANT EDITOR/ PHOTOGRAPHER Julie Culvvell ART DIRECTOR Marta Foutz Published by the Office of Public Affairs for Alumnae and Friends of the College. Agnes Scott College, Decatur, GA 30030 404/373-2571 Contents Spring 1984 Volume 62, Number FEATURES ARTIST BRINGS THE MOUNTAIN HOME hdieCidudi I Agnes Scott art professor Terry McGehee reflects on how her trek in the Himalayas influenced her art. IS THERE LIFE AFTER COLLEGE? Bets_'v Fancher 6 Dean Julia T Gary takes early retirement to pursue a second career as a Methodist minister. 100 YEARS. .. Bt'ts>- ¥a^^c\^er 14 John O. Hint reminisces about his life and his years at Agnes Scott. DANCE FOLK, DANCE ART DANCE, DARLING, DANCE! Julie Culudl 16 Dance historian and professor Marylin Darling studies the revival and origin of folk dance. PROHLE OF A PLAYWRIGHT Betsy Fancher 18 Pulitzer Prize-winning alumna Marsha Norman talks about theatre today and her plays. "THE BEAR" Julie Culwell 22 Agnes Scott's neo-gothic architecture becomes the back- drop for a Hollywood movie on the life of Alabama coach Paul "Bear" Bryant. LESTWEFORGET BetsyFancher 28 A fond look at the pompous Edwardian figure who con- tinues to serve the College long past his retirement. -

275. – Part One

275. – PART ONE 275. Clifford (1994) Okay, here’s the deal: I don’t know you, you don’t know me, but if you are anywhere near a television right now I need you to stop whatever it is that you’re doing and go watch “Clifford” on HBO Max. This is another film that has a 10% score on Rotten Tomatoes which just leads me to believe that all of the critics who were popular in the nineties didn’t have a single shred of humor in any of their non-existent funny bones. I loved this movie when I was seven, and I love it even more when I’m thirty-three. It’s genius. Martin Short (who at the time was forty-four) plays a ten-year-old hyperactive nightmare child from hell. I mean it, this kid might actually be the devil. He is straight up evil, conniving, manipulative and all-told probably causes no less than ten million dollars-worth of property damage. And, again, the plot is so simple – he just wants to go to Dinosaur World. There are so many comedy films with such complicated plots and motivations for their characters, but the simplistic genius of “Clifford” is just this – all this kid wants on the entire planet is to go to Dinosaur World. That’s it. The movie starts with him and his parents on an plane to Hawaii for a business trip, and Clifford knows that Dinosaur Land is in Los Angeles, therefore he causes so much of a ruckus that the plane has to make an emergency landing. -

2011 Kevin & Bean Clips Listed by Date

2011 Kevin & Bean clips listed by date January 03 Monday 01 Opening Segment-2011-01-03-No What It Do Nephew segment.mp3 02 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-6 am.mp3 03 Highlights Of Dick Clark and Ryan Seacrest-New Years Eve-2011-01-03.mp3 04 Harvey Levin-TMZ-2011-01-03.mp3 05 The Internet Round-up-2011-01-03.mp3 06 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-7 am.mp3 07 Thanks For That Info Bean-2011-01-03.mp3 08 Broken New Years Resolutions-2011-01-03.mp3 09 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-8 am.mp3 10 Eli Manning-2011-01-03-Turns 30 Today.mp3 11 Patton Oswalt-2011-01-03-New Book Out.mp3 12 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-9 am-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 13 Dick Clark New Years Eve-More Highlights-2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 14 Calling Arkansas About 2000 Dead Birds-2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 15 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-03-10 am.mp3 January 04 Tuesday 01 Opening Segment-2011-01-04.mp3 02a Bean Did Not Realize It Was King Of Mexicos Birthday-2011-01-04.mp3 02b Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-6 am.mp3 03 Calling Arkansas About 2000 Dead Birds-from Monday 2011-01-03-Patton Oswalt Sits In.mp3 04 and 14 Hotline To Heaven-2011-01-04-Michael Jackson.mp3 05 Oprah Rules In Kevins House-2011-01-04.mp3 06 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-7 am.mp3 07 Strange Addictions-2011-01-04-Listener Call-in.mp3 08 Paula Abdul-2011-01-04-On Her New TV Show.mp3 09 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-8 am.mp3 10 Bean Passed Out On Christmas Eve-2011-01-04-Wife Donna Explains.mp3 11 Psycho Body-2011-01-04.mp3 12 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-9 am.mp3 13 Afro Calls-2011-01-04.mp3 15 Show Biz Beat-2011-01-04-10 am.mp3 -

'House Hunters: Comedians on Couches'

HGTV SPOTLIGHTS COMEDIANS AND THEIR HOUSE-HUNTING COMMENTARY IN NEW JUNE SERIES ‘HOUSE HUNTERS: COMEDIANS ON COUCHES’ New York [May 18, 2020] Fans who miss televised live events and the pithy professional commentary that comes with them can now look to HGTV to fill that void with its new, highly anticipated series House Hunters: Comedians on Couches (fka House Hunters: LOL). In a four- night, star-studded special event at 10 and 10:30 p.m. ET/PT from Tuesday, June 2, through Friday, June 5, America’s favorite contactless past time—watching and commenting on House Hunters—gets a fun new twist when seven popular comedians deliver hilarious, no holds barred, color commentary on classic episodes of the hit series. Together via videoconference, the entertainers will call out the victories and agonizing defeats caused by paint colors, granite countertops, stainless steel appliances and open concept spaces. The House Hunters: Comedians on Couches celebrity lineup is led by Dan Levy and Natasha Leggero and features their comedian friends Whitney Cummings, Eliot Glazer, John Mulaney, Chris Redd and J.B. Smoove. “House Hunters is a pop culture phenomenon that inspires strong reactions from viewers who like to play along with its familiar house selection process,” said Jane Latman, president, HGTV. “While we may not agree with the house each family chooses or the reasons they select it, we can agree that it’s a good time to lean on talented people who can find the humor in everything and make us laugh out loud—even when it comes to the challenges and triumphs of house hunting.” And, the comedic fun on the couch supports a good cause. -

The GRAMMY Museum Presents George Carlin: a Place for My Stuff

The GRAMMY Museum Presents George Carlin: A Place For My Stuff New Display to Open Sept. 30 Commemorating The Late GRAMMY-winning comedian WHO: The GRAMMY Museum will commemorate GRAMMY-winning comedian George Carlin with a new display opening Wednesday, Sept. 30, 2015 on the Museum's third floor. The exhibit will mark the third display in the Museum's comedy series, following previous tributes to Rodney Dangerfield and Joan Rivers. WHAT: Artifacts on display in George Carlin: A Place For My Stuff will include: Carlin's GRAMMY Awards and other accolades Childhood scrapbook and photos The set list from his performances on The Tonight Show in 1962 and The Ed Sullivan Show in 1971 His public arrest records Script from the 1999 cult film Dogma And more "Ever since I became the keeper of my dad's stuff in 2008, I have enjoyed sharing little bits of it with friends and comedians," said Kelly Carlin, the comedian's daughter. "But to know that his fans will now get to see some of it, makes my heart swell with joy. I am thrilled that the GRAMMY Museum is creating a place for his stuff." "George Carlin helped redefine the art form of stand-up comedy. He used his talent to not only entertain, but to question conventional wisdom and social injustices," said Bob Santelli, Executive Director of the GRAMMY Museum. "With this latest display in our comedy series, we continue to spotlight some of the greatest comedy acts, many of whom have been recognized by the GRAMMY Awards." WHEN & WHERE: George Carlin: A Place For My Stuff will be on display at the GRAMMY Museum through March 2016. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. JA Jason Aldean=American singer=188,534=33 Julia Alexandratou=Model, singer and actress=129,945=69 Jin Akanishi=Singer-songwriter, actor, voice actor, Julie Anne+San+Jose=Filipino actress and radio host=31,926=197 singer=67,087=129 John Abraham=Film actor=118,346=54 Julie Andrews=Actress, singer, author=55,954=162 Jensen Ackles=American actor=453,578=10 Julie Adams=American actress=54,598=166 Jonas Armstrong=Irish, Actor=20,732=288 Jenny Agutter=British film and television actress=72,810=122 COMPLETEandLEFT Jessica Alba=actress=893,599=3 JA,Jack Anderson Jaimie Alexander=Actress=59,371=151 JA,James Agee June Allyson=Actress=28,006=290 JA,James Arness Jennifer Aniston=American actress=1,005,243=2 JA,Jane Austen Julia Ann=American pornographic actress=47,874=184 JA,Jean Arthur Judy Ann+Santos=Filipino, Actress=39,619=212 JA,Jennifer Aniston Jean Arthur=Actress=45,356=192 JA,Jessica Alba JA,Joan Van Ark Jane Asher=Actress, author=53,663=168 …….. JA,Joan of Arc José González JA,John Adams Janelle Monáe JA,John Amos Joseph Arthur JA,John Astin James Arthur JA,John James Audubon Jann Arden JA,John Quincy Adams Jessica Andrews JA,Jon Anderson John Anderson JA,Julie Andrews Jefferson Airplane JA,June Allyson Jane's Addiction Jacob ,Abbott ,Author ,Franconia Stories Jim ,Abbott ,Baseball ,One-handed MLB pitcher John ,Abbott ,Actor ,The Woman in White John ,Abbott ,Head of State ,Prime Minister of Canada, 1891-93 James ,Abdnor ,Politician ,US Senator from South Dakota, 1981-87 John ,Abizaid ,Military ,C-in-C, US Central Command, 2003- -

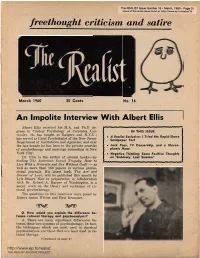

Download This Issue in Text-Searchable PDF Format

The REALIST Issue Number 16 - March, 1960 - Page 01 scans of this entire Issue found at: http://www.ep.tc/realist/16 freethought criticism and satire March 1960 35 Cents No. 16 An Impolite Interview With Albert Ellis Albert Ellis received his M.A. and Ph.D. de grees in Clinical Psychology at Columbia Uni IN THIS ISSUE versity. He has taught at Rutgers and N.Y.U.; • A Realist Exclusive: I Tried the Rapid-Shave has served as Chief Psychologist of the New Jersey Sandpaper Test Department of Institutions and Agencies; and over the last decade he has been in the private practice • Jack Paar, TV Censorship, and a Stereo of psychotherapy and marriage counseling in New phonic Hoax York City. • Negative Thinking: Some Positive Thoughts Dr. Ellis is the author of several books—in on ‘Suddenly, Last Summer' cluding The American Sexual Tragedy, How to ~ ~~ ■----i ^ r ~— i ~ i ii—i ~ n ~ i ~ ir i ~i ~ i t ~ _ - _r Live With a Neurotic and Sex Without Guilt — as well as more than 150 papers in various profes sional journals. His latest book, The Art and Science of Love, will be published this month by Lyle Stuart. Now in preparation, in collaboration with Dr. Robert A. Harper of Washington, is a major work on the theory and technique of ra tional psychotherapy. The questions in this interview were posed by Robert Anton Wilson and Paul Krassner. Q. How would you explain the difference be tween rational therapy and psychoanalysis? A. There are many significant differences be tween, these two systems of psychotherapy.