Comparative Political Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Germanic Surname Lexikon

Germanic Surname Lexikon Most Popular German Last Names with English Meanings German for Beginners: Contents - Free online German course Introduction German Vocabulary: English-German Glossaries For each Germanic surname in this databank we have provided the English Free Online Translation To or From German meaning, which may or may not be a surname in English. This is not a list of German for Beginners: equivalent names, but rather a sampling of English translations of German names. Das Abc German for Beginners: In many cases, there may be several possible origins or translations for a Lektion 1 surname. The translation shown for a surname may not be the only possibility. Some names are derived from Old German and may have a different meaning from What's Hot that in modern German. Name research is not always an exact science. German Word of the Day - 25. August German Glossary of Abbreviations: OHG (Old High German) Words to Avoid - T German Words to Avoid - Glossary Warning German Glossary of Germanic Last Names (A-K) Words to Avoid - With English Meanings Feindbilder German Words to Avoid - Nachname Last Name English Meaning A Special Glossary Close Ad A Dictionary of German Aachen/Aix-la-Chapelle Names Aachen/Achen (German city) Hans Bahlow, Edda ... Best Price $16.95 Abend/Abendroth evening/dusk or Buy New $19.90 Abt abbott Privacy Information Ackerman(n) farmer Adler eagle Amsel blackbird B Finding Your German Ancestors Bach brook Kevan M Hansen Best Price $4.40 Bachmeier farmer by the brook or Buy New $9.13 Bader/Baader bath, spa keeper Privacy Information Baecker/Becker baker Baer/Bar bear Barth beard Bauer farmer, peasant In Search of Your German Roots. -

Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences

Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and other set-theoretic methods distinguish themselves from other approaches to the study of social phenomena by using sets and the search for set relations. In virtually all social science !elds, statements about social phenomena can be framed in terms of set relations, and using set- theoretic methods to investigate these statements is therefore highly valuable. "is book guides readers through the basic principles of set-theory and then on to the applied practices of QCA. It provides a thorough understanding of basic and advanced issues in set-theoretic methods together with tricks of the trade, so#ware handling, and exercises. Most arguments are introduced using examples from existing research. "e use of QCA is increasing rapidly and the application of set theory is both fruitful and still widely mis- understood in current empirical comparative social research. "is book provides the comprehensive guide to these methods for researchers across the social sciences. Carsten Q. Schneider is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science and Founding Director of the Center for the Study of Imperfections in Democracies at Central European University, Hungary. Claudius Wagemann is Professor of Qualitative Social Science Methods at Goethe University, Frankfurt. Strategies for Social Inquiry Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis Editors Colin Elman, Maxwell School of Syracuse University John Gerring, Boston University James Mahoney, Northwestern University Editorial Board Bear Braumoeller, David Collier, Francesco Guala, Peter Hedström, !eodore Hopf, Uskali Maki, Rose McDermott, Charles Ragin, !eda Skocpol, Peter Spiegler, David Waldner, Lisa Wedeen, Christopher Winship !is new book series presents texts on a wide range of issues bearing upon the prac- tice of social inquiry. -

A3344 Publication Title: Membership Applications to the NS-Frauenshcaft

Publication Number: A3344 Publication Title: Membership Applications to the NS-Frauenshcaft/Deutsches Frauenwerk Date Published: n.d. MEMBERSHIP APPLICATIONS TO THE NS-FRAUENSHCAFT/DEUTSCHES FRAUENWERK Introduction Berlin Document Center (BDC) biographic records include membership information for approximately 3.5 million members of the NS Frauenschaft and Deutsches Frauenwerk (National Socialist Women’s Organization), which directed the activities of various women’s organizations in Nazi Germany. Included among the latter were professional organizations, NSDAP women’s auxiliary formations, and humanitarian and educational groups during the 1931-45 period. As with other ‘front’ organizations, NSDAP membership was not required, so that many individuals documented here are not found elsewhere among BDC biographic collections. The Records are organized in two series, reproduced on 2,418 microfilm rolls. The earliest Frauenschaft organizations came into existence in October 1931 as NSDAP women’s auxiliaries. After Hitler came to power in January 1933, the NS-Frauenschaft served as the means by which existing women’s organizations were brought into line with National Socialist principles. Under the direction of Reichsfauenführerin Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, it specialized in political indoctrination of such varied organizations as the Reichsgemeinschaft Deutscher Hausfauen (Reich Community of German Housewives), Bund Deutscher Ärztinnen (League of German Female Physicians), and others. Its organization paralleled that of the Nazi Party, with subordinate -

Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records Created After Sept

Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records Created after Sept. 27, 1906 Alphabetical surname index S History & Genealogy Department St. Louis County Library 1640 S. Lindberg Blvd. St. Louis, Missouri 63131 314-994-3300, ext. 2070 [email protected] Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records Created after Sept. 27, 1906 This index covers St. Louis, Missouri naturalization records created between October 1, 1906 and December 1928 and is based on the following sources: • Naturalizations, U.S. District Court—Eastern Division, Eastern Judicial District of Missouri, Vols. 1 – 82 • Naturalizations, U.S. Circuit Court— Eastern Division, Eastern Judicial District of Missouri, Vols. 5 – 21 Entries are listed alphabetically by surname, then by given name, and then numerically by volume number. Abbreviations and Notations SLCL = History and Genealogy Department microfilm number (St. Louis County Library) FHL = Family History Library microfilm number * = spelling taken from the signature which differed from name in index. How to obtain copies Photocopies of indexed articles may be requested by sending an email to the History and Genealogy Department at [email protected]. A limit of three searches per request applies. Please review the library's lookup policy at https://www.slcl.org/genealogy-and-local- history/services. A declaration of intention may lead to further records. For more information, contact the National Archives at the address below. Include all information listed on the declaration of intention. National Archives, Central Plains Region 400 W. Pershing Rd. Kansas City, MO 64108 (816) 268-8000 [email protected] History Genealogy Dept. Index to St. Louis, Missouri Naturalization Records St. -

The Schneider Family of Nöttingen Germany 1650-1744 and the Snider Family in the Colony and State of South Carolina

The Schneider Family of Nöttingen Germany 1650-1744 And the Snider Family in the Colony and State of South Carolina From 1745 to 1900 by Dewey Gene Snyder Seventh great grandson of Hans Jacob Schneider July 15, 2016 If you can contribute material or your comments Please contact: [email protected] © 2016 Dewey Gene Snyder The Schneider Family of Nöttingen Germany Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... i Table of Figures and illustrations ............................................................................................ iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. ix Elloree Heritage Museum and Cultural Center , Elloree, SC ........................................ ix The Schneider Family from Nöttingen Germany ................................................................... 11 The story behind the story: Nöttingen Germany .................................................................... 12 Explanations of the Plaque Narrative ............................................................................. 16 References for the Schneider Family of Nöttingen Germany ................................................ 18 Descendants of Hans Jacob Schneider b. abt. 1650 ........................................................... 21 Latter Day Saints Family History Center Birth Records ................................................... -

Poster Session Iituesday, December 09, 2014

Neuropsychopharmacology (2014) 39, S291–S472 & 2014 American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. All rights reserved 0893-133X/14 www.neuropsychopharmacology.org Tuesday, December 09, 2014 whether D-serine administration, which reverses these abnormalities at the RNA and protein level, also normalizes the epigenetic perturbations. T1. Altered CREB Binding to Activity-dependent Genes Keywords: CREB, Arc, BDNF, miR132. in Serine Racemase Deficient Mice, a Mouse Model of Disclosure: JTC served as a consultant for EnVivo and Schizophrenia Abbvie in the last 2 years. A patent owned by MGH for the use of D-serine as a treatment for serious mental illness Darrick Balu*, Joseph Coyle could yield royalties for Dr. Coyle. Harvard University, McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts T2. Wnt Signaling, Neurodevelopmental, and Behavioral Background: cAMP-response-element-binding protein Phenotypes in a Dixdc1 Knock-out Mouse Model of (CREB) is a ubiquitously expressed transcription factor in Psychiatric Illness the brain that regulates neuroplasticity by modulating gene expression. There are numerous signaling pathways by Benjamin Cheyette*, Robert Stanley, Pierre-Marie Martin which information is transmitted from the cell membrane to University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco, the nucleus that in turn affects CREB binding to DNA. The California influx of calcium through N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) is a well-defined mechanism that leads to the Background: DIXDC1 encodes a scaffold protein enriched increased expression of CREB-dependent genes, including in neurons that physically interacts with the DISC1 protein brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), microRNA-132 implicated in major mental illness, as well as with the (miR132), and activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated Dishevelled protein central to Wnt/beta-catenin intercellu- protein (Arc). -

Names List 2015.Indd

National Days of Remembrance NAMES LIST OF STEIN, Viktor—From Hungary VICTIMS OF THE HOLOCAUST HOUILLER, Marcel—Perished at Natzweiler This list contains the names of 5,000 Jewish and SEELIG, Karl—Perished at Dachau non-Jewish individuals who were murdered by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1939 BAUER, Ferenc—From Hungary and 1945. Each name is followed by the victim’s LENKONISZ, Lola—Perished at Bergen-Belsen country of origin or place of death. IRMSCHER, Paul—Perished at Neuengamme Unfortunately, there is no single list of those known to have perished during the Holocaust. The list GRZYWACZ, Jan—Perished at Bergen-Belsen provided here is a very small sample of names taken from archival documents at the United States BUGAJSKI, Abraham-Hersh—From Poland Holocaust Memorial Museum. BRAUNER, Ber—From Poland Approximately 650 names can be read in an hour. NATKIEWICZ, Josef—Perished at Buchenwald PROSTAK, Benjamin—From Romania LESER, Julius—Perished at Dachau GEOFFROY, Henri—Perished at Natzweiler FRIJDA, Joseph—Perished at Bergen-Belsen HERZ, Lipotne—From Slovakia GROSZ, Jeno—From Hungary GUTMAN, Rivka—From Romania VAN DE VATHORST, Antonius—Perished at Neuengamme AUERBACH, Mordechai—From Romania WINNINGER, Sisl—From Romania PRINZ, Beatrix—Perished at Bergen-Belsen BEROCVCZ, Estella—Perished at Bergen-Belsen WAJNBERG, Jakob—Perished at Buchenwald FRUHLING, Sandor—From Hungary SOMMERLATTE, Berta—From Germany BOERSMA, Marinus—Perished at Neuengamme DANKEWICZ, Dovid—From Poland ushmm.org National Days of Remembrance WEISZ, Frida—From -

The Family Name As Socio-Cultural Feature and Genetic Metaphor: From

Wayne State University Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints WSU Press 4-1-2012 The family name as socio-cultural feature and genetic metaphor: from concepts to methods Pierre Darlu UMR7206, CNRS, Museú m National d'Histoire Naturelle, Universite ́ Paris 7 Paris Gerrit Bloothooft Utrecht University, Utrecht institute of Linguistics Alessio Boattini Dipartimento di Biologia E.S., Area di Antropologia, Universita ̀ di Bologna Leendert Brouwer Meertens Institute KNAW, Amsterdam Matthijs Brouwer Meertens Institute KNAW, Amsterdam See next page for additional authors Recommended Citation Open access pre-print, subsequently published as Darlu, Pierre; Bloothooft, Gerrit; Boattini, Alessio; Brouwer, Leendert; Brouwer, Matthijs; Brunet, Guy; Chareille, Pascal; Cheshire, James; Coates, Richard; Longley, Paul; Dräger, Kathrin; Desjardins, Bertrand; Hanks, Patrick; Mandemakers, Kees; Mateos, Pablo; Pettener, Davide; Useli, Antonella; and Manni, Franz (2012) "The aF mily Name as Socio-Cultural Feature and Genetic Metaphor: From Concepts to Methods," Human Biology: Vol. 84: Iss. 2, Article 5. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol_preprints/8 This Open Access Preprint is brought to you for free and open access by the WSU Press at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Human Biology Open Access Pre-Prints by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Authors Pierre Darlu, Gerrit Bloothooft, Alessio Boattini, Leendert Brouwer, Matthijs Brouwer, Guy Brunet, Pascal Chareille, James Cheshire, Richard -

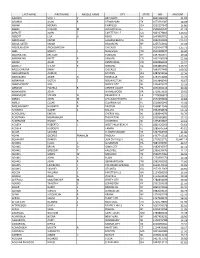

Last Name First Name Middle Name City State Npi Amount

LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME CITY STATE NPI AMOUNT AARONS SCOTT P BAYTOWN TX 1841386919 31.89 ABANDO ALAN R CEDAR PARK TX 1073561387 18.69 ABAWI HEERAN FAIRFIELD OH 1932337649 16.80 ABBAS HUSAIN M JACKSONVILLE FL 1508026527 31.72 ABBOTT JOHN T FAYETTEVILLE GA 1861679805 120.55 ABBOTT LISA G RENO NV 1609883701 11.19 ABDOLLAHI KARIM LAGUNA BEACH CA 1942240403 215.91 ABDUL SATER SARAH BROOKLYN NY 1255742912 17.26 ABDULMASSIH ABDULMASSIH CHICAGO IL 1629045778 135.71 ABEL MARCY J NASHVILLE TN 1952388977 36.60 ABERNATHIE BRENON YONKERS NY 1497916977 20.44 ABERNATHY BRETT B DENVER CO 1437106028 55.98 ABOAF ALAN P CENTENNIAL CO 1003866393 15.57 ABOSEIF SHERIF R OXNARD CA 1093882995 116.39 ABOU GHAYDA RAMY CHICAGO IL 1093257446 109.36 ABOUHOSSEIN AHMAD DAYTON OH 1487693156 12.36 ABOUKASM AMER G ROSEVILLE MI 1194754085 19.26 ABRAHAM VICTOR E WILMINGTON NC 1003848540 46.67 ABRAMOWITZ JOEL JERSEY CITY NJ 1356429377 13.19 ABRAMS PAMELA B CENTER VALLEY PA 1851502215 30.40 ABRAMSON JOHN WYNNEWOOD PA 1710953633 20.02 ABRAMSON STEVEN N PRAIRIEVILLE LA 1720086820 13.21 ABRAN JOHN M CHICAGO HEIGHTS IL 1942293832 14.84 ABREU CESAR R CLEARWATER FL 1518995943 13.44 ABROMOWITZ HOWARD B DAYTON OH 1508812546 49.83 ACHARYA SUJEET S DALLAS TX 1962658674 54.76 ACHOLONU EMEKA CHERRY HILL NJ 1598944076 34.76 ACHUTHAN HEMAMALINI THORNTON CO 1205982881 17.41 ACKERMAN RANDY B VOORHEES NJ 1205893807 30.63 ACOSTA ROBERTO J WEST PALM BEACH FL 1861426306 53.63 ACOSTA RUDOLPH TAMPA FL 1285645564 43.51 ADAIR SANDRA FLOWER MOUND TX 1497784359 31.09 ADAM GEORGE FRANKLIN -

Jewish Genealogy

RESEARCH OUTLINE Jewish Genealogy CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Introduction ............................. 1 This outline introduces records and strategies that Jewish Search Strategies................... 1 can help you learn more about your Jewish Finding Jewish Records in the Family ancestors. It teaches terminology and describes the History Library Catalog ................. 4 content, use, and availability of major Maps of Jews in Europe ................... 7 genealogical records. Archives and Libraries .................... 9 Biography ............................. 11 Using This Outline Business Records and Commerce........... 12 Cemeteries............................. 12 This outline will help you evaluate various records Census................................ 14 and decide which records to search as you trace Chronology ............................ 16 your Jewish ancestors. Records that are uniquely Church Records......................... 17 Jewish are listed, as are other general sources, that Civil Registration........................ 18 may contain the information you are searching for. Concentration Camps .................... 20 These record sources are often created by the Court Records .......................... 21 government or other organizations and list details Directories............................. 21 about all people. Divorce Records ........................ 21 Emigration and Immigration............... 22 This outline discusses in alphabetical order many Encyclopedias and Dictionaries ............ 23 major topics used for genealogical -

Surname 1St Name Middle / Maiden Nm Death Date Cem Pg/Sec Sec

Surname 1st name Middle / Maiden Nm Death Date Cem Pg/Sec Sec/Sid Lot-Gr /Row/ Blk Saak Hoam 8/19/1931 SHcamp 1111 Sabasko Michael 12/20/1943 SHcamp 1590 Sabban Caroline Pernella 12/10/1899 Res A South 72 Sabban Charles Thomas 10/1/1896 Res A South 72 Sabban Grandma Grandma 12/5/1862 Res A South 72 Sabban Henry Henry 6/6/1902 Res A South 72 Sabban Louisa Louisa 10/1/1876 Res A South 72 Sachro Illko 1/5/1930 SHcamp 1043 Sackett Addison L. 2/22/1913 Wdln 114 C 66.2 Sackett Corrilla B (Whitrage) 11/12/1897 Wdln 122 C 38.1 Sackett H. Sibley 5/2/1951 Wdln Sackett Horatio S. 6/2/1920 Wdln Sackett Judah Bennett 4/25/1899 Wdln 122 C 38.2 Sackett Julia A. 9/26/1896 Wdln 114 C 66.3 Sackett Meta E. (Sporing) 6/11/1921 Wdln Sackett Ruth Hortense 3/30/1903 Wdln 114 C 66.1 Sackett? / Travers? Kate not id'd Wdln 114 C 66.4 Sackl Anna Not fd StGrg West 65-8 Sackl Barbara 5/13/1911 StGrg West 65-2 Sackl Elizabeth 12/18/1938 StGrg West 142-4 Sackl George 4/18/1958 StGrg West 142-3 Sackl George 1/30/1881 StGrg West 65-1 Sackl Joseph 3/20/1907 StGrg West 65-1 Sackl Mathilda 10/17/1907 StGrg West 65-3 Sage Annette Emma (Jacobson) 4/4/1975 Res A Nrth B 96W Sahl Gunnor 10/23/1877 Nrslnd 7 212 Sahl Henning O. -

2001 Surname

Surname Given Age Date Page Maiden Note Aaron Charles Ray Sr. 55 12-Aug D-4 Abbot Pearl 93 22-Apr C-6 Abell George Lee 57 1-Feb C-4 Abeyta Frank "Pancho' 53 29-May C-3 Abila Frank Carlos 37 26-Jan C-4 Abram Jason Andre 26 7-Feb C-5 Abramson Michael T. 56 29-Jul D-4 Acevez Maria Jesus 78 27-Jan E-4 Ackerman Elizabeth M. 80 24-Apr C-5 Ackermann Kurt J. 83 26-Jul E-5 Flag included Adam Glen Raymond 57 1-May C-5 Adam Bruce 48 5-Dec D-6 Adame Minnie 73 1-Sep F-5 Amador Adamik Michael 79 27-Dec D-4 Flag included Adamoski Lawrence M. 50 9-Jun E-5 Adamovich Stoja 85 6-Aug D-4 Adams Joseph B. 91 11-Jan D-5 Adams Maxine 84 8-May C-5 Adams Laura Belle 30-Aug E-5 Adams Kevin M. 42 12-May E-7 Adams Georgidean A. 79 7-Jun D-5 Adams Katina 25-Nov D-5 Polyzois Adams Anna V. 83 16-Dec D-6 Slawinski Adams Cleofus 'Clay" 69 29-Nov D-5 Addlesberger Joan 68 5-Sep D-5 Adent Jennie 86 30-Oct D-4 Adler Joan 68 4-Sep D-5 Adorjan Theresa R. 68 19-Sep E-5 Terzarial Agan Carl J. 74 22-Nov C-6 Agee Robert Lee (Bob) 14-Nov E-5 Agnew Charles Arthur 63 8-Jun C-5 Aguilera Josephine C. 49 28-Nov D-4 Cuison Aguilera Wanda Jean 56 11-Aug F-5 Ahlborn Helen A.