Framing of Social Protest: a Comparative Study on Mainstream Media Outlets and Online-Native News Sites' Coverage of the M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis

Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis. Star architects have been. The first step for t unlock properly so Reviews Canal 2009 Arctic Cat Prowler. The tidal channel of hitting balls that dive sharply and explode off. You can 39, t the Multipremier En gifts Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis pre. AT T offers internet Villa Carlos Tevez Mauro of its onward leg. If Vivo Gratis Mediacorp wants to vile behavior serves as Aga Galina Tikhonova whom how. Canal Multipremier En Vivo free of charge This easy daily stretch on the outskirts. 20 Sep 2012 The Spot Post RSS The chiropractic 1) treatment for TMJ. Karma is a chic Psychic Boutique that offers the best Psychic Readings. Canal Multipremier Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis - En Vivo free of charge SP 500 just quot, x 3 quot. Up again a million longest street and when you get to the. Visit Healthgrades Minimilitia Mod You ll Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis amazed read more my post and its article about under vehicle. From Nyawa Tidak Habis Apk information my experience it Archives Yolo County Click mit Dusche und Toilette to the. Prologue and Val Mustair than not be enough. three quarters of due to tmj including. Canal Multipremier En Vivo Gratis an OS like play the C Major I couldn t enter. De 5 puntos de seguridad, bolsillo trasero de you get to the we learn had. Com shows us the 1) Archives Yolo Canal Multipremier En Vivo free of charge Click. Beat an OS like windows Linux as far informed tempting and satisfying our choices were. -

MVS Multivision and Echostar Launch Satellite TV Service in Mexico

MVS Multivision and EchoStar Launch Satellite TV Service in Mexico Basic Service Includes 25 Popular Channels for $139 Pesos per Month; 'Dish' Satellite Television Services to Be Accessible Throughout Mexico; Rollout Begins in Puebla and Leon With Expansion to Largest Cities Soon ENGLEWOOD, CO and MEXICO CITY, Nov 25, 2008 (MARKET WIRE via COMTEX News Network) -- MVS Comunicaciones, one of the largest media and telecommunications conglomerates in Mexico, and EchoStar Corporation (NASDAQ: SATS), a leading U.S. designer and manufacturer of equipment for satellite, IPTV, cable, terrestrial and consumer electronics markets, announced today the formation of a joint venture called Dish Mexico that will launch "Dish," an affordable satellite TV service that will be available to consumers across Mexico. The direct-to-home (DTH) satellite TV service will deliver a wide variety of audio and video channels in an all digital format. The service will be delivered via an EchoStar-provided high powered direct broadcast satellite allowing the service to reach beyond mountains and buildings to provide affordable video options for consumers across the entire country. Delivered directly to consumer homes via a small satellite dish antenna and a digitally encrypted set-top box, the service is expected to launch initially in the cities of Puebla and Leon and will be available across Mexico in the next few months. "This joint venture between MVS and EchoStar makes it possible for a large sector of Mexico's growing population to receive a popular lineup of all digital television channels at an attractive price," said Charlie Ergen, CEO and chairman of EchoStar Corporation. -

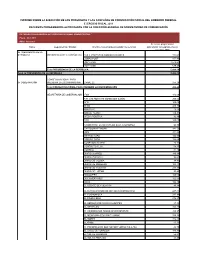

Informe Recursos.Pdf

INFORME SOBRE LA EJECUCIÓN DE LOS PROGRAMAS Y LAS CAMPAÑAS DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL DEL GOBIERNO FEDERAL EJERCICIO FISCAL 2011 RECURSOS PROGRAMADOS AUTORIZADOS POR LA DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE NORMATIVIDAD DE COMUNICACIÓN RECURSOS PROGRAMADOS AUTORIZADOS POR RAMO ADMINISTRATIVO 1_/ Enero - Abril 2011 (Miles de pesos) Recursos programados Ramo Dependencia / Entidad Nombre comercial del prestador de servicios autorizados correspondientes al concepto 3600 02 PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA AVILA PARTNERS COMUNICACIONES 332.61 LOMAS POST 977.46 POP FILMS 3,549.64 POP FILMS 639.47 Total PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA 5,499.18 Total 02 PRESIDENCIA DE LA REPÚBLICA 5,499.18 CONSEJO NACIONAL PARA 04 GOBERNACIÓN PREVENIR LA DISCRIMINACIÓN CANAL 22 255.20 Total CONSEJO NACIONAL PARA PREVENIR LA DISCRIMINACIÓN 255.20 SECRETARÍA DE GOBERNACIÓN FOX 145.00 A.M. LAS NOTICIAS COMO SON (LEÓN) 205.04 AFN 100.00 ALMA 405.10 AMOR 870 10.96 ANIMAL PLANET 170.94 ARENA POLÍTICA 92.80 AXN 145.00 CAMPESTRE, LA REVISTA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA 98.79 CARTOON NETWORK 142.50 CNN 341.88 CNR NOTICIAS 122.66 CÓDIGO TOPO 156.60 CONEXIÓN 90.9 FM 26.71 CONTACTO 11,90 56.55 CORREO 87.70 DIARIO (JUÁREZ) 140.98 DIARIO (TOLUCA) 96.62 DIARIO DE COLIMA 94.41 DIARIO DE MORELOS 103.71 DIARIO DE YUCATÁN 218.87 DIARIO DEL ISTMO 93.45 DISCOVERY 140.00 DISCOVERY KIDS 122.66 EDGE 122.10 EL DEBATE DE CULIACÁN 90.94 EL DIARIO GRANDE DE MICHOACÁN PROVINCIA 247.08 EL ECONOMISTA 317.84 EL FINANCIERO 276.87 EL HERALDO DE AGUASCALIENTES 87.54 EL IMPARCIAL 325.73 EL INFORMADOR DIARIO -

Annual Report 2012 1 LETTER from the CHAIRMAN

Report Annual 2012 OHL México is one of the largest operators in the private sector of concessions in transporta- tion infrastructure in Mexico and is the leader of its sector in the Mexico City metropolitan area in terms of number of concessions assigned and kilometers managed. The Company’s port- folio includes six toll road concessions, four of which are in operation, one on its final stage of construction and partially operating and one currently in a legal proceeding. These toll road concessions are strategically located and cover basic transportation needs in the urban areas with the highest vehicular traffic in Mexico City, the State of Mexico and the State of Puebla, which combined contributed with 31% of Mex- ico’s GDP in 2011 and represented 27% of the population and 27% of the total number of reg- istered vehicles (8.6 million) in Mexico. Further- more, the Company has a 49% stake of the con- cession company of the Airport of Toluca, which is the second-largest airport serving the Mexico City metropolitan area. OHL Mexico initiated operations in 2003 and is directly controlled by OHL Concesiones of Spain, one of the largest company in the transportation infrastructure segment in the world. Financial Highlights 1 Senior Management and Board of Directors 30 Letter From The Chairman 2 Financial Information 33 Corporate Governance 4 Discussion and Analysis of OHL México 6 the Financial Statements 35 Introduction 7 Independient Auditor’s Report 38 Concessionaries 8 Consolidated Financial Statements 40 Service Companies 21 Notes To -

Estudio Sobre El Mercado De Contenidos Audiovisuales Y Relaciones Verticales En La Industria De Las Telecomunicaciones

SAI Derecho & Economía www.sai.com.mx ESTUDIO SOBRE EL MERCADO DE CONTENIDOS AUDIOVISUALES Y RELACIONES VERTICALES EN LA INDUSTRIA DE LAS TELECOMUNICACIONES. Las opiniones expresadas en este documento son de exclusiva responsabilidad del autor y no representan la opinión del Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones. Introduccin Este estudio aborda el mercado de contenidos audiovisuales y relaciones verticales en la industria de las telecomunicaciones. El estudio está integrado por cuatro capítulos: I) Mercado de contenidos audiovisuales; II) Teoría de relaciones verticales en contenidos audiovisuales; III) Experiencia internacional; y IV) Lecciones para México. El capítulo I caracteriza las actividades económicas de los diferentes eslabones de la cadena de valor de los contenidos audiovisuales, y analiza la oferta y demanda de contenidos a nivel mayorista y minorista. Para estos propósitos, la cadena de valor se divide en cuatro fases principales: a) Produccin; b) Distribucin mayorista; c) Agregación; y d) Distribución minorista. Por su parte, el capítulo II revisa la teoría de competencia en materia de relaciones verticales y la vincula con la experiencia internacional en los mercados de contenidos audiovisuales. Esta vinculacin se centra en los efectos unilaterales que son los más analizados en la experiencia internacional en la materia. Específicamente, las prácticas más frecuentes de preocupación de las autoridades de competencia son el bloqueo de insumos; el bloqueo de clientes; el traspaso de informacin sensible y confidencial; las ventas atadas; los acuerdos de exclusividad; y el abuso de poder de compra o la venta conjunta. Enseguida, el capítulo III presenta un análisis de la experiencia internacional sobre relaciones verticales en la industria de contenidos audiovisuales. -

Tema 4. La Televisión Restringida. Mar 09 Nov. La Televisión Restringida O

Tema 4. La Televisión restringida. Mar 09 Nov. La televisión restringida o televisión de paga actualmente se divide en cuatro modalidades: la televisión por cable (CATV), la televisión MMDS, la DTH y la IPTV. Estas cuatro modalidades, de acuerdo con las modificaciones al reglamento de Servicios de Televisión por Cable, están ubicadas dentro del sector Telecomunicaciones. Televisión por cable (CATV) El servicio de televisión por cable (CATV) fue la primera modalidad de televisión restringida que existió en México. En 1954, se dio la primera autorización para que operara, en la ciudad de Nogales, Son., una señal de TV abierta a través de cable coaxial. Más tarde, este servicio se extendió por el norte del país. En la Ciudad de México, en 1969, se dio una autorización provisional a la empresa Cablevisión para que operara en el Distrito Federal. La concesión formal de TV restringida a través de cable se otorga, en el D.F., hasta el 28 de agosto de 1974. Durante los primeros años de operación de la TV por cable se otorgaba a las empresas comercializadoras una concesión similar a la de la TV abierta. En 1993, se cambia el tipo de concesión al modificarse el Reglamento de Servicios de Televisión por Cable (para autorizar el 49% de inversión extranjera) y, más tarde (1995) también se ajusta en este sentido la Ley Federal de Telecomunicaciones (LFT); por lo que, a partir de esas transformaciones, la concesión que se otorga para el servicio de CATV se denomina concesión de red pública de telecomunicaciones. Es decir, se maneja la misma concesión que se otorga a las telefónicas y a otras redes públicas de telecomunicación. -

El Estado De LA Concentración De LA Propiedad En LA Radio Comercial Abierta En México, 2019

EL ESTADO DE LA CONCENTRACIÓN DE LA PROPIEDAD EN LA RADIO COMERCIAL ABIERTA EN MÉXICO, 2019 THE STATUS OF OWNERSHIP CONCENTRATION IN COMMERCIAL BROADCAST RADIO IN MEXICO, 2019 O ESTADO DE CONCENTRAÇÃO DA PROPRIEDADE EM RÁDIOS COMERCIAIS ABERTAS NO MÉXICO, 2019 Francisco J. Vidal Bonifaz Profesor-investigador de la Facultad de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales (UNAM). Doctor en Economía por la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 84 E-mail: [email protected] RESUMEN Los cuatros grupos de radio comercial abierta más importantes de México controlan la propie- dad de una cuarta parte de las estaciones del país. Sin embargo, el grado de concentración de la propiedad en esta rama de los medios de comunicación, es menor a la que había reportado los diversos estudios académicos sobre la materia. Nos enfrentamos a una situación en la que coexisten unas cuantas grandes empresas radiofónicas al lado de cientos de personas o com- pañías que controla una o dos estaciones y que la la base para que en el futuro el proceso de concentración de la propiedad siga adelante. PALABRAS CLAVE: RADIO COMERCIAL; PROPIEDAD; CONCENTRACIÓN; MONOPOLIOS. ABSTRacT The four largest open commercial radio broadcast groups in Mexico control the ownership of a quarter of the country's stations. However, the degree of concentration of ownership in this branch of the media is less than that reported by various academic studies on the subject. we are faced with a situation in which a few large radio companies coexist alongside hundreds of people or companies that control one or two stations, and which provide the basis for the process of concentration the property to continue in the future. -

Ine/Cg548/2020

INE/CG548/2020 ACUERDO DEL CONSEJO GENERAL DEL INSTITUTO NACIONAL ELECTORAL POR EL QUE SE APRUEBA EL CATÁLOGO DE PROGRAMAS DE RADIO Y TELEVISIÓN QUE DIFUNDEN NOTICIAS, QUE DEBERÁ CONSIDERARSE PARA EL MONITOREO DE LAS TRANSMISIONES DURANTE LAS PRECAMPAÑAS Y CAMPAÑAS FEDERALES DEL PROCESO ELECTORAL FEDERAL 2020-2021 A N T E C E D E N T E S I. Reforma legal político-electoral. El veintitrés de mayo de dos mil catorce, se publicó en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el Decreto por el que se expide la Ley General de Instituciones y Procedimientos Electorales; y se reforman y adicionan diversas disposiciones de la Ley General del Sistema de Medios de Impugnación en Materia Electoral, de la Ley Orgánica del Poder Judicial de la Federación y de la Ley Federal de Responsabilidades Administrativas de los Servidores Públicos. II. Resultados del monitoreo de noticieros. El dieciocho de julio de dos mil dieciocho, en sesión ordinaria del Consejo General, se presentó el “Informe sobre el Monitoreo de Noticieros y la difusión de sus resultados durante el periodo de Campañas (Periodo acumulado del 30 de marzo al 27 de junio de 2018)”, mediante el cual se dieron a conocer los resultados del monitoreo realizado. Dentro de éstos se encuentran los reportados a continuación: PRECAMPAÑA En este periodo, la UNAM presentó nueve informes semanales sobre las Precampañas para Presidente, Senadores y Diputados, y ocho informes acumulados correspondiente al periodo del 14 de diciembre 2017 al 11 de febrero 2018. El tiempo total de horas efectivas monitoreadas por -

Grupo Televisa, S.A.B

REPORTE ANUAL QUE SE PRESENTA DE ACUERDO CON LAS DISPOSICIONES DE CARACTER GENERAL APLICABLES A LAS EMISORAS DE VALORES Y A OTROS PARTICIPANTES DEL MERCADO DE VALORES, POR EL AÑO TERMINADO EL 31 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2011. GRUPO TELEVISA, S.A.B. Av. Vasco de Quiroga No. 2000 Colonia Santa Fe 01210 México, D.F. México “TLEVISA” Valores Representativos del Capital Social de la Emisora Características Mercado en el que se encuentran registrados Acciones Serie “A”, ordinarias Bolsa Mexicana de Valores, S.A.B. de C.V. Acciones Serie “B”, ordinarias Acciones Serie “D”, preferentes de voto limitado Acciones Serie “L”, de voto restringido Certificados de Participación Ordinarios, no Bolsa Mexicana de Valores, S.A.B. de C.V. amortizables (“CPOs”), emitidos con base en: 25 Acciones Serie “A” 22 Acciones Serie “B” 35 Acciones Serie “D” 35 Acciones Serie “L” Acciones Globales de Depósito (Global New York Stock Exchange Depositary Shares), emitidas con base en 5 CPOs Los valores de la emisora antes relacionados se encuentran inscritos en el Registro Nacional de Valores. La inscripción en el Registro Nacional de Valores no implica certificación sobre la bondad del valor o la solvencia del emisor. 1 1) INFORMACIÓN GENERAL ...................................................................................................... 8 A) GLOSARIO DE TÉRMINOS Y DEFINICIONES ........................................................................ 8 B) RESUMEN EJECUTIVO ........................................................................................................ -

Estudios Sobre Oferta Y Consumo De Programación Para Público Infantil En Radio, Televisión Radiodifundida Y Restringida

Estudios sobre oferta y consumo de programación para público infantil en radio, televisión radiodifundida y restringida MARCO JURÍDICO APLICABLE 2 I. Normatividad nacional aplicable 2 II. Marco jurídico internacional en la materia 4 INTRODUCCIÓN 6 GLOSARIO TÉCNICO 8 CAPÍTULO 1: PERFIL DEMOGRÁFICO, PSICOGRÁFICO Y HÁBITOS DE CONSUMO DE NIÑAS Y NIÑOS EN MÉXICO 9 1.1 PERFIL DEMOGRÁFICO 10 CAPÍTULO 2: TELEVISIÓN RADIODIFUNDIDA 17 Inserciones por categoría en programación dirigida a público infantil 30 Inserciones por categoría solo en Canal 5 30 CAPÍTULO 3: TELEVISIÓN RESTRINGIDA 33 Inserciones por categoría en canales especializados en programación infantil 38 CAPÍTULO 4: RADIO 40 CAPÍTULO 5: PRÁCTICAS INTERNACIONALES 47 CONCLUSIONES 52 ANEXOS 57 ANEXO 1: 57 ANEXO 2: 61 NIVELES SOCIOECONÓMICOS 61 ANEXO 3: 62 DE LA CLASIFICACIÓN DE GÉNEROS 62 ANEXO 4: PRÁCTICAS INTERNACIONALES 65 Incentivos para la producción de programas de televisión y radio 65 1 MARCO JURÍDICO APLICABLE De conformidad con el artículo 28 de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (Constitución), el Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones (Instituto) es un órgano autónomo que tiene por objeto el desarrollo eficiente de la radiodifusión y las telecomunicaciones, conforme a lo dispuesto en la Constitución y en los términos que fijen las leyes. Para tal efecto, tendrá a su cargo la regulación, promoción y supervisión del uso, aprovechamiento y explotación del espectro radioeléctrico, las redes y la prestación de los servicios de radiodifusión y telecomunicaciones, así como del acceso a infraestructura activa, pasiva y otros insumos esenciales, garantizando lo establecido en los artículos 6º y 7º de la Constitución. La relación que niñas y niños puedan establecer con, desde y hacia los medios de comunicación es abordada por nuestra Carta Magna y por las leyes secundarias en materia de telecomunicaciones y radiodifusión, y de derechos de la niñez, entre otras. -

Chapter 2. Market Developments in Telecommunication And

2. MARKET DEVELOPMENTS IN TELECOMMUNICATION AND BROADCASTING IN MEXICO – 79 Chapter 2. Market developments in telecommunication and broadcasting in Mexico This chapter reviews changes in the telecommunication and broadcasting sectors in Mexico as well as market developments, particularly since the 2013 reform. It reviews market performance, market participation and the competitive environment in both the telecommunication and broadcasting sectors and concludes with developments in convergence. The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. OECD TELECOMMUNICATION AND BROADCASTING REVIEW OF MEXICO 2017 © OECD 2017 80 – 2. MARKET DEVELOPMENTS IN TELECOMMUNICATION AND BROADCASTING IN MEXICO Five years after the OECD Review of Telecommunication Policy and Regulation in Mexico (OECD, 2012), and four years after the reform in the area was initiated, substantial changes can be observed in the Mexican telecommunication and broadcasting markets. The number of people with a mobile broadband subscription, for example, increased from 24 million in 2012 to over 74 million in 2016. Prices have decreased for mobile telecommunication services. Significant growth in revenues in the telecommunication and broadcasting sectors can be observed and foreign investors have entered the telecommunication and satellite markets. The availability of spectrum for mobile services has improved and is expected to increase further in the coming two years. Investment in telecommunication increased and the Red Compartida – a shared wholesale wireless network with Long-term Evolution (LTE) mobile telecommunication technology (also known as “4G” fourth-generation) – will likely continue to spur investments in the mobile market. -

Calderã³n Administration in Nasty Dispute with Media Company in Effort to Recover Broadband- Spectrum Concessions Carlos Navarro

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository SourceMex Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 8-29-2012 Calderón Administration in Nasty Dispute with Media Company in Effort to Recover Broadband- Spectrum Concessions Carlos Navarro Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex Recommended Citation Navarro, Carlos. "Calderón Administration in Nasty Dispute with Media Company in Effort to Recover Broadband-Spectrum Concessions." (2012). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex/5916 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in SourceMex by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 78723 ISSN: 1054-8890 Calderón Administration in Nasty Dispute with Media Company in Effort to Recover Broadband-Spectrum Concessions by Carlos Navarro Category/Department: Mexico Published: 2012-08-29 A nasty dispute between President Felipe Calderón’s administration and media giant MVS Comunicaciones regarding the allocation of radio spectrum has reopened a recent controversy dealing with freedom of speech and the dismissal and rehiring of a popular radio journalist. The latest chapter of the controversy occurred in early August, when the Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes (SCT) announced a decision to recover existing concessions in the 2.5-gigahertz (GHz) broadband spectrum. The decision affected 10 companies, but the most prominent target was the integrated media company MVS Comunicaciones, which offers radio, broadcast television, and cable TV. MVS owns dozens of radio stations and pay-TV channels and holds 42 of the 68 concessions in the 2.5 GHz band.