Download Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Greens Farms Academy Upper School English Summer Reading 2014

GREENS FARMS ACADEMY UPPER SCHOOL ENGLISH SUMMER READING 2014 ASSIGNED SUMMER READING BOOKS BY GRADE AND COURSE TITLE: ENGLISH 9: Travels with Charley: In Search of America, John Steinbeck ISBN: 0-14-018741-3 ENGLISH 10: Purple Hibiscus, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie ISBN: 1-61620-241-6 Choice book titles (CHOOSE ONE from this list): Frankenstein, Mary Shelley Lord of the Flies, William Golding The Farming of Bones, Edwidge Danticat Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Lisa See ENGLISH 11 and 11H: The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald ISBN: 007432-7356-7 ENGLISH 12 FALL ELECTIVES and AP ENGLISH: New World Voices A Thousand Splendid Suns, Khaled Hosseini ISBN: 1-59448-385- X Moby Dick and the Poetry of Perception The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time, Mark Haddon ISBN: 1-4000-3271-7 Creative Writing: Non- Fiction Slouching Toward Bethlehem, Joan Didion ISBN: 0-374-53138-2 Great Books Franny and Zooey, J. D. Salinger ISBN: 0-316-76949-5 A.P. English Wuthering Heights, Emily Bronte ISBN: 0-14-143955-6 PLEASE SEE THE PAGES THAT FOLLOW FOR SUGGESTED SUMMER READING TITLES AND RECOMMENDATIONS. 9th I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Angelou (F) The Dollmaker, Arnow (F) The Da Vinci Code, Brown (F) The Perks of Being a Wallflower, Chbosky (F) North of Beautiful, Chen (F) Sailing around the Room, Collins (poetry) My Losing Season, Conroy (A) The Chocolate War, Cormier (F) The Andromeda Strain, Crichton (SF) Rebecca, Du Maurier (M) Gandhi, Fisher (B) Mary Queen of Scots, Fraser (HF) y The Fault in Our Stars, Green (F) Death Be Not Proud, Gunther -

Heritage Jr/Sr High School Book Level Points Author Title 6.5 9 Gray

Heritage Jr/Sr High School Book Level Points Author Title 6.5 9 Gray, Elizabeth Janet Adam of the Road 4.9 5 Taylor, Sydney All-of-a-Kind Family 6.5 5 Yates, Elizabeth Amos Fortune, Free Man 4.8 8 Krumgold, Joseph And Now Miguel 4.3 2 Haywood, Carolyn B Is for Betsy 4.9 6 Salten, Felix Bambi 4 3 Lovelace, Maud Hart Betsy-Tacy 7.7 11 Sewell, Anna Black Beauty (Unabridged) 6.5 6 Gates, Doris Blue Willow 5.3 5 Norton, Mary Borrowers, The 4.6 5 Paterson, Katherine Bridge to Terabithia 5.6 7 Henry, Marguerite Brighty of the Grand Canyon 5 10 Speare, Elizabeth George Bronze Bow, The 6 8 Brink, Carol Ryrie Caddie Woodlawn 6.2 3 Sperry, Armstrong Call It Courage 4.1 8 Latham, Jean Carry on, Mr. Bowditch 5.9 2 Coatsworth, Elizabeth Cat Who Went to Heaven, The 6 5 McCloskey, Robert Centerburg Tales 4.4 5 White, E.B. Charlotte's Web 4.8 5 Dahl, Roald Charlie and the Chocolate Factory 3.9 1 Dalgliesh, Alice Courage of Sarah Noble, The 4.9 4 Selden, George Cricket in Times Square, The 7.7 4 Daugherty, James Daniel Boone 4.9 3 Cleary, Beverly Dear Mr. Henshaw 6.2 4 Angeli, Marguerite De Door in the Wall, The 3.8 3 Haywood, Carolyn Eddie and Gardenia 4.2 3 Haywood, Carolyn Eddie and the Fire Engine 3.7 3 Haywood, Carolyn Eddie's Green Thumb 4.7 5 Konigsburg, E.L. From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. -

Literature, CO Dime Novels

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 068 991 CS 200 241 AUTHOR Donelson, Ken, Ed. TITLE Adolescent Literature, Adolescent Reading and the English Class. INSTITUTION Arizona English Teachers Association, Tempe. PUB DATE Apr 72 NOTE 147p. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Ill. 61801 (Stock No. 33813, $1.75 non-member, $1.65 member) JOURNAL CIT Arizona English Bulletin; v14 n3 Apr 1972 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *English; English Curriculum; English Programs; Fiction; *Literature; *Reading Interests; Reading Material Selection; *Secondary Education; Teaching; Teenagers ABSTRACT This issue of the Arizona English Bulletin contains articles discussing literature that adolescents read and literature that they might be encouragedto read. Thus there are discussions both of literature specifically written for adolescents and the literature adolescents choose to read. The term adolescent is understood to include young people in grades five or six through ten or eleven. The articles are written by high school, college, and university teachers and discuss adolescent literature in general (e.g., Geraldine E. LaRoque's "A Bright and Promising Future for Adolescent Literature"), particular types of this literature (e.g., Nicholas J. Karolides' "Focus on Black Adolescents"), and particular books, (e.g., Beverly Haley's "'The Pigman'- -Use It1"). Also included is an extensive list of current books and articles on adolescent literature, adolescents' reading interests, and how these books relate to the teaching of English..The bibliography is divided into (1) general bibliographies,(2) histories and criticism of adolescent literature, CO dime novels, (4) adolescent literature before 1940, (5) reading interest studies, (6) modern adolescent literature, (7) adolescent books in the schools, and (8) comments about young people's reading. -

Timeless Classics – Summer Reading List

Timeless Classics – Reid School Summer Reading List Kindergarten Coatsworth, Elizabeth Keith, Harold through Grade 6 The Cat Who Went to Heaven 5.0 Rifles for Watie 7.0 *Recommended for K-3, either for Dalgliesh, Alice Kelly, Eric reading by children or for reading The Bears on Hemlock The Trumpeter of Krakow 4.0 to them. Mountain* 4.0 Kipling, Rudyard The Courage of Sarah Noble* 2.9 Captains Courageous 4-5 Adamson, Joy De Angeli, Marguerite Just So Stories for Little 7.8 Born Free 7-8 N The Door in the Wall Children* Aesop De Jong, Meindert N The Jungle Book N Fables* The House of Sixty Fathers 5.1 Kjelgaard, Jim Alcott, Louisa May The Wheel on the School 6.0 Big Red 5.0 Little Women 9.0 Dodge, Mary Mapes Knight, Eric Andersen, Hans Christian Hans Brinker, or the Silver Lassie Come Home 4.0 Krumgold, Joseph Fairy tales 4.0 Skates 4.0 ...and Now Miguel 5-6 Atwater, Richard and Florence Du Bois, William Pene Onion John 6.0 Mr. Popper’s Penguins* 5-6 The Twenty-One Balloons 5.0 La Farge, Oliver Bailey, Carolyn Sherwin Edmonds, Walter D. N Laughing Boy N Miss Hickory The Matchlock Gun 3.0 Lamb, Charles and Mary Barrie, J.M. Estes, Eleanor Tales from Shakespeare Ginger Pye 5-6 Peter Pan 4.0 Latham, Jean Lee Baum, L. Frank Moffats series 5-6 Carry on, Mr. Bowditch 9.0 Farley, Walter The Wonderful Wizard of Oz 5-6 Lawson, Robert The Black Stallion 5-6 Bemelmans, Ludwig Ben & Me 5.0 Field, Rachel Madeline series* 3.0, 5-6 N Rabbit Hill Hitty, Her First Hundred Bond, Michael (series) 4.0-6.0 Leaf, Munro Years 4.0 A Bear Called Paddington The Story of Ferdinand* 3.0 Boston, L.M. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1989 Naked Once More by 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show Best Contemporary Novel Elizabeth Peters by Richard Laymon (Formerly Best Novel) 1988 Something Wicked by 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub Carolyn G. Hart 1998 Bag Of Bones by Stephen 2017 Glass Houses by Louise King Penny Best Historical Novel 1997 Children Of The Dusk by 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Janet Berliner Penny 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen 2015 Long Upon The Land by Bowen King Margaret Maron 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates 2014 Truth Be Told by Hank by Catriona McPherson 1994 Dead In the Water by Nancy Philippi Ryan 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. Holder 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank King 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub Philippi Ryan 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1992 Blood Of The Lamb by 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by Bowen Thomas F. Monteleone Louise Penny 2013 A Question of Honor by 1991 Boy’s Life by Robert R. 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret Charles Todd McCammon Maron 2012 Dandy Gilver and an 1990 Mine by Robert R. 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Unsuitable Day for McCammon Penny Murder by Catriona 1989 Carrion Comfort by Dan 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise McPherson Simmons Penny 2011 Naughty in Nice by Rhys 1988 The Silence Of The Lambs by 2008 The Cruelest Month by Bowen Thomas Harris Louise Penny 1987 Misery by Stephen King 2007 A Fatal Grace by Louise Bram Stoker Award 1986 Swan Song by Robert R. -

Oliver Twist Jude the Obscure Sons and Lovers Dostoevsky, Fyodor

Chaucer, Geoffrey . 821.1 C496 Faulkner, William .................... F263 Hugo, Victor ....................... H895 The Canterbury Tales Absalom, Absalom Les Misérables Chopin, Kate ........................ C549 As I Lay Dying Huxley, Aldous ..................... H986 The Awakening The Sound and the Fury Brave New World Clark, Walter V.T. ................... C5962 Fielding, Henry ...................... F459 James, Henry........................ J273 The Ox-Bow Incident The History of Tom Jones The Portrait of a Lady Conrad, Joseph ..................... C7543 Fitzgerald, F. Scott.................... F553 The Turn of the Screw Lord Jim The Great Gatsby Joyce, James ......................... J89 Nostromo Tender Is the Night A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man . Cooper, James F. .................... C7774 Flaubert, Gustave . F587 Ulysses The Deerslayer Madame Bovary Kafka, Franz ......................... K11 The Last of the Mohicans Forster, E.M . F733 The Castle Crane, Stephen . C8917 A Passage to India The Trial The Red Badge of Courage García Márquez, Gabriel ............. G216 Kerouac, Jack ....................... K397 Dante, Alighieri................ 851.1 D192 One Hundred Years of Solitude On the Road The Divine Comedy Gogol, Nikolai...................... G613 Kesey, Ken .......................... K42 Defoe, Daniel ...................... D314 Dead Souls One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest Robinson Crusoe Golding, William.................... G619 Kipling, Rudyard ...................... K57 Dickens, Charles .................... D548 Lord -

Pulitzer Lit P 2020

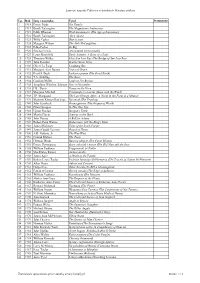

Laureaci nagrody Pulitzera w dziedzinie literatury pi ęknej Lp. Rok Imi ę i nazwisko Tytuł Przeczytane 1 1918 Ernest Poole His Family 2 1919 Booth Tarkington The Magnificent Ambersons 3 1921 Edith Wharton Wiek niewinno ści (The Age of Innocence) 4 1922 Booth Tarkington Alice Adams 5 1923 Willa Cather One of ours 6 1924 Margaret Wilson The Able McLaughlins 7 1925 Edna Ferber So Big 8 1926 Sinclair Lewis Arrowsmith (Arrowsmith) 9 1927 Louis Bromfield Early Autumn: A Story of a Lady 10 1928 Thornton Wilder Most San Luis Rey (The Bridge of San Luis Rey) 11 1929 Julia Peterkin Scarlet Sister Mary 12 1930 Oliver La Farge Laughing Boy 13 1931 Margaret Ayer Barnes Years of Grace 14 1932 Pearl S. Buck Łaskawa ziemia (The Good Earth) 15 1933 T.S. Stribling The Store 16 1934 Caroline Miller Lamb in His Bosom 17 1935 Josephine Winslow Johnson Now in November 18 1936 H.L. Davis Honey in the Horn 19 1937 Margaret Mitchell Przemin ęło z wiatrem (Gone with the Wind) 20 1938 J.P. Marquand The Late George Apley: A Novel in the Form of a Memoir 21 1939 Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Roczniak (The Yearling) 22 1940 John Steinbeck Grona gniewu (The Grapes of Wrath) 23 1942 Ellen Glasgow In This Our Life 24 1943 Upton Sinclair Dragon's Teeth 25 1944 Martin Flavin Journey in the Dark 26 1945 John Hersey A Bell for Adano 27 1947 Robert Penn Warren Gubernator (All the King's Men) 28 1948 James Michener Tales of the South Pacific 29 1949 James Gould Cozzens Guard of Honor 30 1950 A.B. -

The American Scene

March, 1935] THE VIRGINIA TEACHER 51 AMERICAN IDEALS—THE a better understanding of the American AMERICAN SCENE scene and American trends. Although a study of English literature has An Annotated Reading List always played an important role in our course of study, we welcome a list of books THE purpose of this study is two- from English educators, suggesting what in fold : (1) an approach to American literature best expresses English thought literature in line with contemporary today. educational thought; and (2) a suggested But America offers to England a more exchange list for English students, of ma- perplexing problem in understanding than terial which would help them better to un- does the latter to us. It is difficult for derstand the American scene. After con- Englishmen, whose traditions and institu- siderable discussion the committee decided tions have evolved slowly and steadily that it should consider as a basis for selec- through more than a thousand years, to un- tion the following questions: derstand our country, which, in one hundred 1. Does it portray a phase of the and fifty years, has developed through pro- American scene? gressive periods of exploration and pioneer- 2. Does it represent the thought of a ing endeavor into a great world power. large mass of people? We faced the questions; What literature 3. Is it literature? will best convey to another people the con- No book could meet all three tests. We ception of the composite nature of the thought it should approach two of them. American scene? What would point the We sought material which attained to at way to the contribution which America with least a fair level of expression, including her heterogeneous background eventually the "good book of the hour" as well as that will add to human experience? We found which may be the "book of all time." it necessary to consider the following con- Because we felt some kind of classifica- stituent factors which, woven together, give tion would be helpful we designated certain us the tapestry of American thought: categories. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Diverse heritage: exploring literary identity in the American Southwest Author(s) Costello, Lisa Publication date 2013 Original citation Costello, L. 2013. Diverse heritage: exploring literary identity in the American Southwest. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2013, Lisa Costello http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information No embargo required Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1155 from Downloaded on 2021-10-04T05:40:54Z Table of Contents Page Introduction The Spirit of Place: Writing New Mexico........................................................................ 2 Chapter One Oliver La Farge: Prefiguring a Borderlands Paradigm ………………………………… 28 Chapter Two ‘A once and future Eden’: Mabel Dodge Luhan’s Southwest …………………......... 62 Chapter Three Opera Singers, Professors and Archbishops: A New Perspective on Willa Cather’s Southwestern Trilogy…………………………………………………… 91 Chapter Four Beyond Borders: Leslie Marmon Silko’s Re-appropriation of Southwestern Spaces ...... 122 Chapter Five Re-telling and Re-interpreting from Colonised Spaces: Simon Ortiz’s Revision of Southwestern Literary Identity……………………………………………………………………………… 155 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 185 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………. 193 1 Introduction The Spirit of Place: Writing New Mexico In her landmark text The American Rhythm, published in 1923, Mary Austin analysed the emergence and development of cultural forms in America and presented poetry as an organic entity, one which stemmed from and was irrevocably influenced by close contact with the natural landscape. Analysing the close connection Native Americans shared with the natural environment Austin hailed her reinterpretation of poetic verse as “the very pulse of emerging American consciousness” (11). -

Students: These Are Possible Choices for Your Summer Reading Books

Students: These are possible choices for your summer reading books. Students, make sure you discuss with your parents(s)/guardian(s) what you choose to read remembering these are choices and some may have delicate material. If you choose one from here, it is preapproved by your teachers. If you want to read something different than what is on this list, you must get your book to your current English teacher no later than Thursday, May 23. To get a different book approved, you must bring the book to your current teacher and allow the teacher time to check readability specific for you before checking out for the summer. There is no guarantee for approval. Remember to choose at your level. Don’t read something too easy for you. Challenge yourself as well as choose a book you will love. Some of these you may check out from the school but must return in the fall, or you will be charged for it. The following are NOT choices because they are used in classes: Les Miserables, Count of Monte Cristo, Frankenstein, Hound of the Baskervilles, Black Like Me, Tale of Two Cities, A Separate Peace, The Scarlet Letter, Ethan Frome, My Antonia, Huckleberry Finn¸ The Crucible, Fahrenheit 451, The Giver, Night, Julius Caesar , Great Expectations, To Kill a Mockingbird, Anne Frank, I Heard the Owl Call My Name, Guts, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, Esperanza Rising Grade Level Book Author Genre School has this Recommendation book for checkout if you desire 7-8 Touching Spirit Ben Mikaelsen fiction X (SR) Bear Every Soul a Star Wendy Mass fiction Outsiders S.E. -

Reading List: Carson City High School

Reading List: Carson City High School Author Title Description Notes Samplings of American Literature *Agee, James A Death in the Story of loss and heartbreak felt when a young father dies. Family Anaya, Bless Me Ultima Anya espresses his Mexican-American heritage by Rudolpho combining traditional folklore, Spanish storytelling and ancient Mexican mythology. This novel, for which Anaya won a literary award for the best in Chicano novels, concerns a young boy growing up in New Mexico in the late 1940’s. *Baldwin, James Go Tell It On the Semi-autobiographical novel about a 14-year-old black Mountain youth's religious conversion. *Bellamy, Looking Written in 1887 about a young man who travels in time to a Edward Backward: 2000- utopian year 2000, where economic security and a healthy 1887 moral environment have reduced crime. *Bellow, Saul Seize the Day A son grapples with his love and hate for an unworthy father. *Bradbury, Ray Fahrenheit 451 Reading is a crime, and firemen burn books in this futuristic society. Buck, Pearl The Good Earth Nobel-prize winner Buck’s novel focuses upon the rise of Wang Lung, a Chinese peasant, from poverty to the life of a Rick landowner. O-lan, his patient wife, aids his success. Burns, Olive Cold Sassy Tree Set in a turn-of-the-century Georgia town, Cold Sassy Tree Ann details the coming of age of Will Tweedy as he adjusts to his grandfather’s hasty marriage to a much younger woman. Cather, Willa My Antonia Cather’s novel portrays the life of Bohemian immigrant and American setters in the Nebraska frontier.