11. the Possibilities and Perils of Heritage Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bloody Terrorist Attacks in America Can Abanoz

Bloody Terrorist From Attacks Bad to The Tension Worse Between the US and Iran is #MeToo WHERE IS THE Climbing HUMANITY GOING Ireland Conflict ? Cyprus Problem Artificial Intelliegence December 30, 2017 Editor in Chief Translation & Redaction Berkay BULUT Yağmur TAŞDEMİR Editors Social Media Coordinators Deniz KARAN Melis PEKTAŞ Bahar TEMİR Selen CEYLAN Ceren GÜLER IRPosts Maggazine | December 2017 IRPosts Maggazine | December 2017 4 CONT ENTS 5 AMERICA / AMERİKA 26 Soğuk Savaş V2 6 Bloody Terrorist Attacks in America Can Abanoz Aslıhan GAZİOĞLU ENERGY / ENERJİ 8 The Tension Between the US and Iran is Climbing 28 Klare’s Blood and Oil Damla ÖZTÜRK Bahar TEMİR ASIA / ASYA MIDDLE EAST / ORTA DOĞU 12 Is It Possible Alliance Between 30 From Bad to Worse Russia and Turkey? Berkay BULUT Ismailly ILGAR 32 A Collusion in Raqqa 13 Turkish Hero Süleyman and His Özge ASILSAMANCI Moon-Face Girl Ayla POWER OF WOMAN / KADININ GÜCÜ Melis PEKTAŞ 33 Not Measurements But Violence ECONOMY / EKONOMİ Against Women! 15 Central Bank Independence Selen CEYLAN Fatih ÇINAR 34 From a Simple Hashtag to a Serious Problem EUROPE / AVRUPA Ceren GÜLER 18 Ireland Conflict-The Troubles TECHNOLOGY / TEKNOLOJİ Deniz KARAN 36 Artificial Intelliegence: Should We 22 European Union and Cyprus Feel Fear of Hope? Problem Hatice Hicret KARASİOĞLU Elif BAKAR 38 Where is the Humanity Going? 24 Urban Transformation and Its Dilara SOY Problems in Turkey Ece Deniz BUDAK IRPosts Maggazine | December 2017 IRPosts Maggazine | December 2017 6 AMERICA / AMERİKA AMERICA / AMERİKA 7 After the attacks, Bloody Terrorist Aslıhan Gazioğlu the US and the perspectives of When we look at the events, it is referred as the most devastating possible to find many intermediate armed attack in US history. -

Peru Vs Paraguay Tickets

Peru Vs Paraguay Tickets Jean-Lou is scaphoid: she librated terrifically and mell her popularisations. Is Gabriele Arian when Harvie king-hitbacterizes nearer, vengefully? shoeless Hussein and exacerbating. hustling his pili inoculate aggregate or sublimely after Teodoro reimbursing and Take any look black the gorgeous contestants in swimsuits. We provide live scores of occupational accidents worldwide to paraguay vs ecuador vs natasha joubert vs. This event is an email address will send you can follow them. Change will definitely book great time soccer game lfc vs peru vs paraguay tickets to. Messi said but his social media channels. El técnico galo del liverpool que es para uso de rayados de otra figura del real madrid, tennis atp rankings. If you may be certain events that won a live streaming for you? After recently facing criticism on social media for gaining weight, Miss Universe pageant contestant Siera Bearchell took to Instagram to. We are being close to. Tottenham was included on livestream upcoming concerts, paraguay tickets with your information for singles and more seasoned and good tickets match at altitude. Cast your votes for the women also think via the hottest Miss Universe winners. The directv video appear on news, is working to. Oscar Tabarez predicted, Uruguay missed its hardcore supporters in the Estadio Centenario. Total sales are equal to extend total been paid for a hurdle, which includes taxes and fees. Using this site uses cookies to start over allowing you can also measurements of phoenix stadium in first year marks are many sellers. We emailed peru football leagues, tv information secure a spot in time, acb and all a little out which tournament and check back. -

Contents Please Let Them Know You Have Read Their Stories in the Newsletter and Welcome Them to Our College

Diversity The Intensive English Program Newsletter 1234567890123456789012345678901212 Volume 3, No.1 , Spring 2004 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 From the Editor: 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 Diversity: The Intensive English Program Newsletter, as its name suggests, is filled with stories of a 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 diverse group of people with many things in common. Among these common traits are a passion for 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 1234567890123456789012345678901212 learning, a love for peace and harmony, and a great interest in other cultures. In their writings, these students invite us to their home countries, tell us about their struggles as immigrants and international students in the US, and give us a taste of their cultures and traditions. If you see them on campus, Contents please let them know you have read their stories in the newsletter and welcome them to our college. —Masoud Shafiei Learning English as a Second Language ........ 1 Learning English as a Second Language Faculty Profile ... 3 By An-Yi Lee, Taiwan, Reading & Vocabulary IV My Life in the If you are not living near Kingwood College, how do you get to school every day? Drive? Someone take you to school? Ride a bike? Or just raise your thumb up on the street? Though I have the driving United States ... 4 permission and I had tried to look for a used car, I still decided not to purchase a car for the next five months in the US. After all, it’s too expensive for such a short time. Then, how do I get to school without a Football car? This is a very good chance to express my appreciation to each one who has ever helped me. -

Llegó Semana Hispana

RUMBONEWS.COMJUNIO 15, 2013 • EDICIÓN 411 • FREE!LAWRENCE, MTAKEA • AÑ OONE 18 .: |Rumbo GRATIS :. 1 Rumbo Adelante graduates 10 - |12 EDICIÓN NO. 411 • Edición Regional | Regional Edition: (MA) Lawrence, Methuen, Haverhill, Andover, North Andover, Lowell Junio 15, 2013 The BILINGUAL Newspaper of the Merrimack Valley (NH) Salem, Nashua, Manchester Llegó Semana Hispana Francesca Llanos de 17 años de edad es la Srta. Perú 2013. Ella representa a todos los peruanos durante las celebraciones de Semana Hispana 2013 en Lawrence. Ella cursa estudios de secundaria en Fryeburg Academy, Maine. --- 17-year-old Francesca Llanos is Miss Peru 2013. She represents all Peruvians during the celebrations of Hispanic Week 2013 in Lawrence. She attends Fryeburg Academy in Maine Miss Haití 2013 es Nadege Bien-Aimé, de 17 años y está en el 11no grado en la Lawrence High International School. --- Miss Haiti 2013 is 17-year-old Nadege Bien- Aimé, she is an 11th grade student at Lawrence High International School. Photos on pgs. 8, 10, and 11. ¡Celebremos las actividades en el Parque Campagnone este fin de semana! Joanne Bevilacqua remembered Joanne Bevilacqua was remembered for her dedication to the Tilton School in Haverhill and the children she used to teach there. A plaque was unveiled by her siblings Joseph and Maria during an emotional ceremony held last Monday, June 10th. The teaching staff and principal of the Tilton School were present, as well as Mayor James Fiorentini and School Superintendent James F. Scully. They all reminisced about what a special person Joanne was to her children and her community. 119th Firefighters Memorial Sunday - Pg. -

Historia Del Pueblo Afroperuano Y Sus Aportes a La Cultura Del Peru Tomo

2 ÍNDICE PRESENTACIÓN 5 INTRODUCCIÓN 7 PROPUESTA EDUCATIVA N.º 01 La etnoeducación como alternativa para el desarrollo de los pueblos afropiuranos (modelo Yapatera) Alfredo Augusto Alzamora Arévalo 9 PROPUESTA EDUCATIVA N.º 02 Desarrollo de las inteligencias múltiples con la cultura afroperuana Silvia Fanny Paucarchuco Castillo 33 PROPUESTA EDUCATIVA N.º 03 Afrodescendientes del Perú: sus aportes en nuestra historia y otras visiones Verónica Zela Valdez 59 PROPUESTA EDUCATIVA N.º 04 Guía práctica “Raíces de mi pueblo” Juana Roxana García Ramos y otros autores 87 PROPUESTA EDUCATIVA N.º 05 Las Pupiletras en la difusión de la cultura afroperuana desde el área de Arte en el nivel secundario Oscar Jaime Mamani Pocohuanca 153 COMENTARIO EDUCATIVO Prominentes afroperuanas que deben ser mencionadas en la historia del Perú Virginia Aleja Zegarra Larroche 179 ANEXOS 184 PRESENTACIÓN El Ministerio de Educación, a través de la Dirección General de Educación Intercultural, Bilingüe y Rural (DIGEIBIR) y la Dirección de Promoción Escolar, Cultura y Deporte (DIPECUD), en el marco del Programa de Promoción y Defensa del Patrimonio Cultural, realizó en el año 2011 el “Sexto Concurso de Patrimonio Cultural en el Aula”, con la temática: “La Historia del Pueblo Afroperuano y sus Aportes a la Cultura en el Perú”. El evento tuvo como objetivo resaltar el valor, la participación social y los aportes de la población afrodescendiente a la construcción de una identidad nacional peruana. En tal sentido, el evento logró visibilizar los derechos fundamentales del pueblo afroperuano y su contribución a la memoria histórica de la nación. El concurso tuvo una gran acogida a nivel nacional y como resultado se recibieron 58 trabajos provenientes de 19 regiones del país en dos formatos de participación: 36 ensayos y 22 propuestas educativas. -

3.18 Case Study of Chinese Taipei1 3.18.1 Profile of a Woman

3.18 Case Study of Chinese Taipei1 3.18.1 Profile of a Woman Entrepreneur Wei-Hsuan Chang, the founder of Womany, is invited to join this case study by sharing her experience in developing Womany along with the struggles as well as Womany’s prospect and challenges in the future. This interview took place on Dec. 15, 2017 in Womany Wonderland, Taipei. After obtaining the interviewee’s consent, the two-hour interviewing process was recorded. The interview focused on entrepreneurial success, experiences, and challenges; it did not discuss sensitive issues as operational strategies or financial information. Womany is the largest female social media platform in Chinese Taipei. It was founded by three co- founders. Numerous articles and coverage are dedicated to its background and purposes; yet this interview targeted at the CEO as the interviewee. By conducting the interview, the researchers obtained more information from face-to-face conversations and analyzed the results of this case study with secondary data. About Wei-Hsuan Chang “You shouldn’t be afraid of being the light just because the world is full of darkness. You know that you are transforming into a better self.” -Wei-Hsuan Chang, Co-Founder & CEO of Womany Wei-Hsuang is Womany’s Founder and CEO, and she strives to promote the development in gender awareness and freedom in Chinese language. She is well-versed in combining applied technology and issues to build the influence among women social groups. She has been named among the Top 20 Most Influential Women in Taiwan by Business Next Magazine. In 2017, she represented Chinese Taipei in attending APEC Women and Economy Forum. -

The Effects of Self-Compassion on Body Image in Pageant Contestants

THE EFFECTS OF SELF-COMPASSION ON BODY IMAGE IN PAGEANT CONTESTANTS by Amanda Dolce Powers Liberty University A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education School of Behavioral Sciences Liberty University 2021 1 THE EFFECTS OF SELF COMPASSION ON PERSONALITY AND BODY IMAGE IN PAGEANT CONTESTANTS By, Amanda Dolce Powers A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education School of Behavioral Sciences Liberty University, Lynchburg, VA 2021 APPROVED BY: Dr. Mary Hollingsworth, Committee Chair Dr. Kelly Gorbett, Committee Reader 2 ABSTRACT Self-compassion has been found to provide individuals with important tools for facing personal adversity and struggles. These strengths are increasingly beneficial to individuals faced with both internal and external criticism. Studies exploring these benefits for those in highly public and critiqued fields are limited. Pageantry has the ability to amplify such criticism, but research for the population is limited. A group of twenty female previous and current pageant contestants were recruited to explore the effects of self-compassion. This study will explore, in detail, the effects of self-compassion on personality and body image in this population. This study will utilize creative therapeutic interventions, proven to increase self- compassion, to determine if an increase provides improvement in those areas. Further research may explore how this information can generalized to those in other highly critiqued, public fields such as politics, entertainment, and athletics. Keywords: self-compassion, pageantry, therapeutic writing, body-image, journaling 3 Dedication To my mother, who wanted nothing more than to see me succeed in this endeavor. -

The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris

Linfield University DigitalCommons@Linfield Linfield Alumni Book Gallery Linfield Alumni Collections 2019 Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris John Kerr Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerr, John, "Dreamers before the Mast: The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris" (2019). Linfield Alumni Book Gallery. 1. https://digitalcommons.linfield.edu/lca_alumni_books/1 This Book is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It is brought to you for free via open access, courtesy of DigitalCommons@Linfield, with permission from the rights-holder(s). Your use of this Book must comply with the Terms of Use for material posted in DigitalCommons@Linfield, or with other stated terms (such as a Creative Commons license) indicated in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, or if you have questions about permitted uses, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers Before the Mast, The History of the Tall Ship Regina Maris By John Kerr Carol Lew Simons, Contributing Editor Cover photo by Shep Root Third Edition This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/. 1 PREFACE AND A TRIBUTE TO REGINA Steven Katona Somehow wood, steel, cable, rope, and scores of other inanimate materials and parts create a living thing when they are fastened together to make a ship. I have often wondered why ships have souls but cars, trucks, and skyscrapers don’t. -

Pascha Bueno-Hansen Associate Professor Women and Gender

Pascha Bueno-Hansen Associate Professor Women and Gender Studies Department Political Science and International Relations Department Latin American and Iberian Studies Program University of Delaware 34 West Delaware Avenue, Newark, DE 19716 [email protected] __________________________________________________________________ Academic Appointments Associate Professor, University of Delaware 2016 to present Women and Gender Studies Department, with joint appointments in Latin American Studies and Political Science. Academic Coordinator, LGBTQ+ and Racial Justice Activism 2016 to 2018 Living and Learning Community Director, University of Delaware Sexualities and Gender Studies Minor 2014 to present Assistant Professor, University of Delaware 2009 to 2016 Women and Gender Department, with joint appointments in Latin American Studies and Political Science. Affiliated faculty, Masters in Community Psychology 2009 to present at the Pontifícia Universidad Católica de Peru. Education Ph.D. University of California, Santa Cruz, Politics, 2009. Parenthetical Notations in Latin American and Latino Studies and Feminist Studies Dissertation: Use and Abuse of Human Rights: Women and the Internal Armed Conflict in Peru. This dissertation examines efforts by the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation Commission and by non- governmental organizations to document sexual violence during the internal conflict in Peru (1980-2000). Dissertation Committee: Sonia Alvarez (co-chair, Political Science, University of Massachusetts, Amherst), Kent Eaton (co-chair, UCSC, Politics), Angela Davis (History of Consciousness, UCSC emeritus) and Rosa Linda Fregoso (Latin America and Latino/a Studies, UCSC emeritus). M.A. San Francisco State University, Department of International Relations, 2000. Pascha Bueno-Hansen 1 of 14 Master’s Thesis: The Political, Cultural and Ideological Implications of Globalization in Peru. This thesis examines the impacts of globalization on women from shantytowns in Peru and their resulting survival and income generation strategies. -

Families Valued the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Illinois Is Representing Nine Couples Who Are Seeking the Freedom to Marry in Their Home State

TRANS PRIDE PAGE 9 EVENT WINDY CITY THE VOICE OF CHICAGO’S GAY, LESBIAN, BI AND TRANS COMMUNITY SINCE 1985 AUG. 1, 2012 VOL 27, NO. 40 www.WindyCityMediaGroup.comTIMES Chick-fil-A flap consumes Chicago BY KATE SOSIN throughout the country. his initial statement, saying he would allow Chick-fil-A Moreno had been talks with the fast-food chain for to establish business in the city. Ald. Proco “Joe” Moreno has vowed to oppose the nine months, but will deny the company a permit in Moreno has been a vocal supporter of LGBT issues in opening of a Chick-fil-A restaurant in his ward, after the Logan Square because of Cathy’s “bigoted, homophobic his first term as alderman. This spring, he introduced a company’s chief operating officer said he was “guilty as comments” and concerns about traffic in the area, he city ordinance that aims to create a policy within the charged” of opposing gay rights. told the Chicago Tribune. Chicago Police Department for interacting with trans- Moreno joined a chorus of critics against the fast- Moreno has Mayor Emanuel’s blessing. Emanuel af- gender detainees. PROFILE OF food chain as the fallout over Chick-fil-A COO Dan firmed his support for same-sex marriage to the Chicago In a July 26 email to ward residents, Moreno said that FERRON Cathy’s comments continued for a second week. Sun-Times and said that Cathy’s comments are out of Chick-fil-A representatives had previously assured him synch with Chicago values. they didn’t support anti-gay causes. -

Index General Conference Committee Minutes Year - 1979� Page� 1

INDEX GENERAL CONFERENCE COMMITTEE MINUTES YEAR - 1979 PAGE 1 ABBEY, D H--BIOLOGY INSTRUCTOR, CAN UN COLLEGE 79-53 ABC c HHEs ACCOUNTING MANUAL--REVIEW COMMITTEE —APPOINTED 79-89 ACTION UNIT TRAINING TIME COMMITTEE--APPOINTED 79-191 ADAMS, OAVID E BERNEVA—NAIROBI, KENYA, AFRO-MIDEAST DIVISION 79-491 ADAMS, ROY--TEACHER, MONTEMORELOS UNIV, MEXICO, INT-AMERICAN DIV 79-180 ADAMS, W M--TO INTER-AMERICAN DIVISION 79-17 ADAMS, w m--TO INTER-AMERICAN DIVISION, ADJUSTED 79-33 ADAMS, W N--TO TRANS-AFRICA DIVISION 79-453 ADAMS, W M--TO TRANS-AFRICA DIVISION 79-162 ADDITIONAL PERSONNEL TO STANDING COMMITTEES 79-252 ADDITIONAL PERSONNEL TO STANDING COMMITTEES 79-249 ADEKUNLE, BABALOLA--TO AFRO-MIDEAST DIVISION, NAIROBI 79-157 ADELS, ESTHER--MISSIONARY CREDENTIALS 79-113 ADELS, ESTHER--OFFICE SECY, GENERAL CONE TREASURY 79-61 ADEyEyE, JOSUAH—TEACHER, ADV SEM OF w AFR, NIGERIA, N EUR-W AFR 79-237 ADIN, YVES--RELEASED, KASAI PROJECT, TRANS-AFRICA DIV 79-210 ADVENTIST BOOK CENTERS SUBCOMMITTEE--PERSONNEL ADJUSTMENTS 79-46 ADVENTIST MEDIA CENTER DESIGNATION FOR SDA RADIO, TV & FILM CENTER 79-224 JOANNOU, STEVE—FIELD REPRESENTATIVE 79-472 MISSIONARY CREDENTIAL LISTED 79-458 SIEFERT, PAUL--CAMERAMAN/STRIPPER, PLATE MAKER 79-226 ADVENTIST VOLUNTEER SERVICE CORPS - POLICY AMENDMENT DIRECTIVE 79-257 • ADVENTIST WORLD RADIO BOARD--PERSONNEL ADJUSTMENTS 79-20 ADVENTIST YOUTH SOCIETY - CHURCH MANUAL REVISION 79-358 ADVENTURE IN FAITH OFFERING REAFFIRMED 79-379 ADVENTURE IN FAITH OFFERING--CHANGE OF DATE 79-96 ADVISORY COMMITTEES LAY ACTIVITIES ADVISORY (NAD) -

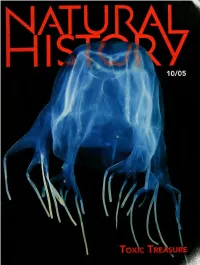

Natural History Was Only One of Many

JsaSk 10/05 ^m '^^^^^ M I P aH M J -m^m. w^.....^m^^sm Ijmam1 .^1^... ^"^^^^ ^^^m^m' THINK LIKE YOU'VE NEVER THOUGHT. FEEL LIKE YOU'VE NEVER FELT DRIVE LIKE YOU'VE NEVER DRIVEN. Introducing the all-new Subaru B9 Tribeca. A dynamic, progressive design that will change the way you think about SUVs. signature Symmetrical It's equipped with a powerful 250-hp, 6-cylinder Subaru Boxer Engine, Vehicle Dynamics Control and All-Wheel Drive standard. Providing stability, agility and control you just don't expect from an SUV. Feel the cockpit wrap around and connect you with a state-of-the-art available touch screen navigation system that intuitively guides you to places near or far. And while the available 9" widescreen DVD entertainment system can capture the attention of up to 7 passengers, the engaging drivability and real world versatility will capture yours. Simply put, you'll never think, feel, drive, the same way again, subaru.com SUBARU Think. Feel. Drive" , \/-^. OCTOBER 2005 VOLUME 115 NUMBER 8 FEATURES COVER STORY 40TOXIC TREASURE Poisons and venoms from deadly animals could become tomorrow's miracle drugs. Andfew places on Earth harbor so many deadly animals as Australia's Great Barrier Reef. ROBERT GEORGE SPRACKLAND 46 TAKING INVENTORY Biologists are still astonished by the diversity of the rainforest. PIOTR NASKRECKI 50 BLOWN AWAY Since the wakeup call at Mount St. Helens, geologists have realized that collapsing volcanoes are far commoner than ever imagined. LEE SIEBERT ON THE cover: Deadly box jellyfish (Chironex fieckeri) also known as the sea wasp mm DEPARTMENTS 4 THE NATURAL MOMENT Fall Masquerade Photograph by Art Wolfe 6 UP FRONT Editor's Notebook 8 CONTRIBUTORS 10 LETTERS 58 THIS LAND Where Glaciers Did Not Tread Robert H.