SCOTT-THESIS.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Focus the Making of the Visitors

People Need Love – the first ABBA song Waterloo was ABBA’s first single, right? Yes – and no. Join us as we explore the story behind People Need Love, the very first single released by the group that later reached worldwide fame under the name ABBA. Party people failure In this day and age, when pop stars with little previous stage experience achieve instant number one hits through participation in television shows such as Pop Idol and American Idol, it is sobering to be reminded how long it actually took before ABBA achieved worldwide success. Although many in the 1970s regarded the four Swedes as a ”manufactured” band, very much along the lines of the groomed, styled and choreographed overnight sensations of the early 21st Century, nothing could be further from the truth. Not only had the individual members spent a decade performing, touring and recording in earlier groups or as solo artists before they grabbed the world’s attention with ’Waterloo’ in April 1974, by that time ABBA themselves had already been making pop music together for two years – and four years had passed since they first attempted a collaboration. Confused? Read on. The early 1970s was a somewhat insecure period for Björn, Benny, Agnetha and Frida. Benny had left his previous group, The Hep Stars, and although Björn was still making records with his group, the Hootenanny Singers, he knew he couldn’t count on them for any future career advancement. Furthermore, Björn and Benny wanted to focus their attention on their partnership in songwriting and record producing, and perhaps not be performers so much anymore. -

The Cultural Significance of Web-Based Exchange Practices

The Cultural Significance of Web-Based Exchange Practices Author Fletcher, Gordon Scott Published 2006 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Arts, Media and Culture DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2111 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/365388 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au The Cultural Significance of Web-based Exchange Practices Gordon Scott Fletcher B.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts, Media and Culture Faculty of Arts Griffith University September 2004 2 Abstract This thesis considers the cultural significance of Web-based exchange practices among the participants in contemporary western mainstream culture. The thesis argues that analysis of these practices shows how this culture is consumption oriented, event-driven and media obsessed. Initially, this argument is developed from a critical, hermeneutic, relativist and interpretive assessment that draws upon the works of authors such as Baudrillard and De Bord and other critiques of contemporary ‘digital culture’. The empirical part of the thesis then examines the array of popular search terms used on the World Wide Web over a period of 16 months from September 2001 to February 2003. Taxanomic classification of these search terms reveals the limited range of virtual and physical artefacts that are sought by the users of Web search engines. While nineteen hundred individual artefacts occur in the array of search terms, these can classified into a relatively small group of higher order categories. Critical analysis of these higher order categories reveals six cultural traits that predominant in the apparently wide array of search terms; freeness, participation, do-it-yourself/customisation, anonymity/privacy, perversion and information richness. -

QU-Alumni Review 2019-3.Pdf

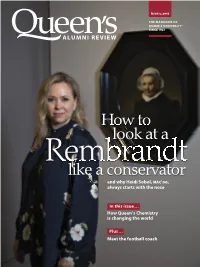

Issue 3, 2019 THE MAGAZINE OF QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY Queen’s SINCE 1927 ALUMNI REVIEW How to Rembrandtlook at a like a conservator and why Heidi Sobol, MAC’00, always starts with the nose In this issue … How Queen’s Chemistry is changing the world Plus … Meet the football coach 4 years to earn your degree. #"""""! !! • Program runs May-August • Earn credits toward an MBA • Designedforrecent graduates "" • Broaden your career prospects • "" " "" ""! 855.933.3298 [email protected] smithqueens.com/gdb "" "" contents Issue 3, 2019, Volume 93, Number 3 Queen’s The magazine of Queen’s University since 1927 queensu.ca/alumnireview ALUMNI REVIEW 2 From the editor 7 From the principal 8 Student research: Pharmacare in Canada 24 Victor Snieckus: The magic of chemistry 29 Matthias Hermann: 10 15 The elements of EM HARM EM TINA WELTZ WELTZ TINA education COVER STORY Inspired by How to look at a Rembrandt 36 Rembrandt Keeping in touch like a conservator Poet Steven Heighton (Artsci’85, Heidi Sobol, mac’00, explores the techniques – ma’86) and artist Em Harm take 46 and the chemistry – behind the masterpieces. inspiration from a new addition The Chemistry medal to The Bader Collection. 48 Your global alumni network 50 Ex libris: New books from faculty and alumni ON THE COVER Heidi Sobol at the Royal Ontario Museum’s exhibition “In the Age of Rembrandt: Dutch Paintings from the 20 33 Museum of Fine Arts, BERNARD CLARK CLARK BERNARD BERNARD CLARK CLARK BERNARD Boston” PHOTO BY TINA WELTZ Pushing the boundaries Meet the coach of science New football coach Steve Snyder discusses his coaching style and the Dr. -

The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: an Analysis of The

THE CURIOUS CASE OF CHINESE FILM CENSORSHIP: AN ANALYSIS OF THE FILM ADMINISTRATION REGULATIONS by SHUO XU A THESIS Presented to the School of Journalism and Communication and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Shuo Xu Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the School of Journalism and Communication by: Gabriela Martínez Chairperson Chris Chávez Member Daniel Steinhart Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded December 2017 ii © 2017 Shuo Xu iii THESIS ABSTRACT Shuo Xu Master of Arts School of Journalism and Communication December 2017 Title: The Curious Case of Chinese Film Censorship: An Analysis of Film Administration Regulations The commercialization and global transformation of the Chinese film industry demonstrates that this industry has been experiencing drastic changes within the new social and economic environment of China in which film has become a commodity generating high revenues. However, the Chinese government still exerts control over the industry which is perceived as an ideological tool. They believe that the films display and contain beliefs and values of certain social groups as well as external constraints of politics, economy, culture, and ideology. This study will look at how such films are banned by the Chinese film censorship system through analyzing their essential cinematic elements, including narrative, filming, editing, sound, color, and sponsor and publisher. -

A History of X: 100 Years of Sex in Film by Luke Ford

A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film By Luke Ford Nowadays, it’s difficult to imagine our lives without the Internet as it offers us the easiest way to access the information we are looking for from the comfort of our homes. There is no denial that books are an essential part of life whether you use them for the educational or entertainment purposes. With the help of certain online resources, such as this one, you get an opportunity to download different books and manuals in the most efficient way. Why should you choose to get the books using this site? The answer is quite simple. Firstly, and most importantly, you won’t be able to find such a large selection of different materials anywhere else, including PDF books. Whether you are set on getting an ebook or handbook, the choice is all yours, and there are numerous options for you to select from so that you don’t need to visit another website. Secondly, you will be able to download A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film pdf in just a few minutes, which means that you can spend your time doing something you enjoy. But, the benefits of our book site don’t end just there because if you want to get a certain by Luke Ford A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film, you can download it in txt, DjVu, ePub, PDF formats depending on which one is more suitable for your device. As you can see, downloading A History Of X: 100 Years Of Sex In Film By Luke Ford pdf or in any other available formats is not a problem with our reliable resource. -

P E R F O R M I N G

PERFORMING & Entertainment 2019 BOOK CATALOG Including Rowman & Littlefield and Imprints of Globe Pequot CONTENTS Performing Arts & Entertainment Catalog 2019 FILM & THEATER 1 1 Featured Titles 13 Biography 28 Reference 52 Drama 76 History & Criticism 82 General MUSIC 92 92 Featured Titles 106 Biography 124 History & Criticism 132 General 174 Order Form How to Order (Inside Back Cover) Film and Theater / FEATURED TITLES FORTHCOMING ACTION ACTION A Primer on Playing Action for Actors By Hugh O’Gorman ACTION ACTION Acting Is Action addresses one of the essential components of acting, Playing Action. The book is divided into two parts: A Primer on Playing Action for Actors “Context” and “Practice.” The Context section provides a thorough examination of the theory behind the core elements of Playing Action. The Practice section provides a step-by-step rehearsal guide for actors to integrate Playing Action into their By Hugh O’Gorman preparation process. Acting Is Action is a place to begin for actors: a foundation, a ground plan for how to get started and how to build the core of a performance. More precisely, it provides a practical guide for actors, directors, and teachers in the technique of Playing Action, and it addresses a niche void in the world of actor training by illuminating what exactly to do in the moment-to-moment act of the acting task. March, 2020 • Art/Performance • 184 pages • 6 x 9 • CQ: TK • 978-1-4950-9749-2 • $24.95 • Paper APPLAUSE NEW BOLLYWOOD FAQ All That’s Left to Know About the Greatest Film Story Never Told By Piyush Roy Bollywood FAQ provides a thrilling, entertaining, and intellectually stimulating joy ride into the vibrant, colorful, and multi- emotional universe of the world’s most prolific (over 30 000 film titles) and most-watched film industry (at 3 billion-plus ticket sales). -

The Contestants the Contestants

The Contestants The Contestants CYPRUS GREECE Song: Gimme Song: S.A.G.A.P.O (I Love You) Performer: One Performer: Michalis Rakintzis Music: George Theofanous Music: Michalis Rakintzis Lyrics: George Theofanous Lyrics: Michalis Rakintzis One formed in 1999 with songwriter George Michalis Rakintzis is one of the most famous Theofanous, Constantinos Christoforou, male singers in Greece with 16 gold and Dimitris Koutsavlakis, Filippos Constantinos, platinum records to his name. This is his second Argyris Nastopoulos and Panos Tserpes. attempt to represent his country at the Eurovision Song Contest. The group’s first CD, One, went gold in Greece and platinum in Cyprus and their maxi-single, 2001-ONE went platinum. Their second album, SPAIN Moro Mou was also a big hit. Song: Europe’s Living A Celebration Performer: Rosa AUSTRIA Music: Xasqui Ten Lyrics:Toni Ten Song: Say A Word Performer: Manuel Ortega Spain’s song, performed by Rosa López, is a Music:Alexander Kahr celebration of the European Union and single Lyrics: Robert Pfluger currency. Rosa won the hearts of her nation after taking part in the reality TV show Twenty-two-year-old Manuel Ortega is popular Operacion Triunfo. She used to sing at in Austria and his picture adorns the cover of weddings and baptisms in the villages of the many teenage magazines. He was born in Linz Alpujarro region and is now set to become one and, at the age of 10, he became a member of of Spain’s most popular stars. the Florianer Sängerknaben, one of the oldest boys’ choirs in Austria. CROATIA His love for pop music brought him back to Linz where he joined a group named Sbaff and, Song: Everything I Want by the age of 15, he had performed at over 200 Performer:Vesna Pisarovic concerts. -

Revisiting Kracauer

In the Frame - Fleetingly: revisiting Kracauer Siegfried Kracauer, University of Birmingham September 13-14 2002 A report by Janet Harbord, Goldsmiths College, University of London, UK In History: The Last Things before the Last, Kracauer described his project as "the rehabilitation of objectives and modes of being which still lack a name and hence are overlooked and misjudged" (Kracauer, 1969: n.p.). To a great extent, this concept of "rehabilitation" ("to restore privileges or reputation") underscored the main thematic of the conference, to locate Kracauer on the map of critical thought as one who has been both overlooked and misjudged. Certainly the history of late publication and translation of Kracauer's work bears testimony to a fundamental neglect in Anglophone cultures at least. As Graeme Gilloch notes, even in Germany, Kracauer's work has far less circulation than his contemporaries of the postwar period, Benjamin, Adorno and Horkheimer. Perhaps, as Gilloch suggests, Kracauer's troubled relations with his contemporaries provided a filter through which his work has become placed, antagonistically and problematically, as the optimistic reading of mass culture as distraction. Yet, already this sense of Kracauer as optimist sits uncomfortably with his later post-war work. Indeed, any retrospective of Siegfried Kracauer's work has to deal with the volume and the duration of the writing, stretching from the early Weimer essays to the latter postwar work on Caligari and film theory. Whilst this provides a rich archive of achievement for contemporary scholars, the conceptual framework shifts as the critical focus moves across objects and decades, denying Kracauer any singular philosophical or disciplinary "home". -

Copyright Law and the Commoditization of Sex

COPYRIGHT LAW AND THE COMMODITIZATION OF SEX Ann Bartow* I. COPYRIGHT LAW PERFORMS A STRUCTURAL ROLE IN THE COMMODITIZATION OF SEX ............................................................................ 3 A. The Copyrightable Contours of Sex ........................................................ 5 B. Literal Copying is the Primary Basis for Infringement Allegations Brought by Pornographers ................................................ 11 1. Knowing Pornography When One Sees It ...................................... 13 C. Sex Can Be Legally Bought and Sold If It Is Fixed in a Tangible Medium of Expression ........................................................................... 16 II. THE COPYRIGHT ACT AUTHORIZES AND FACILITATES NON- CONTENT-NEUTRAL REGULATION OF EXPRESSIVE SPEECH ........................ 20 III. HARMFUL PORNOGRAPHY IS ―NON-PROGRESSIVE‖ AND ―NON- USEFUL‖ ....................................................................................................... 25 A. Pornography as Cultural Construct ...................................................... 25 B. Toward a Copyright Based Focus on Individual Works of Pornography ......................................................................................... 35 1. Defining and Promoting Progress .................................................. 37 2. Child Pornography ......................................................................... 39 2. Crush Pornography ........................................................................ 42 3. “Revenge Porn” -

Subjetividade E Pornô Online: Uma Análise Institucional Do Discurso

UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO INSTITUTO DE PSICOLOGIA THIAGO EMANUEL LUZZI GALVÃO Subjetividade e pornô online: uma análise institucional do discurso Versão Corrigida São Paulo 2017 UNIVERSIDADE DE SÃO PAULO INSTITUTO DE PSICOLOGIA THIAGO EMANUEL LUZZI GALVÃO Subjetividade e pornô online: uma análise institucional do discurso Versão Corrigida Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Psicologia da Universidade de São Paulo para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia Programa de Pós-Graduação em Psicologia Escolar e do Desenvolvimento Humano. Área de Concentração: Instituições Educacionais e Formação do Indivíduo Orientadora: Prof.ª Livre Docente Marlene Guirado São Paulo 2017 1 AUTORIZO A REPRODUÇÃO E DIVULGAÇÃO TOTAL OU PARCIAL DESTE TRABALHO, POR QUALQUER MEIO CONVENCIONAL OU ELETRÔNICO, PARA FINS DE ESTUDO E PESQUISA, DESDE QUE CITADA A FONTE. 2 FOLHA DE AVALIAÇÃO LUZZI, T. E. Subjetividade e pornô online: uma análise institucional do discurso. 2017. 270 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Psicologia) – Instituto de Psicologia, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, 2017. Aprovado em:_______________________ Banca Examinadora: Profª Livre Docente Marlene Guirado (Orientadora) Instituição: Instituto de Psicologia – Universidade de São Paulo (IP/USP) Julgamento: ________________________________________________ Prof. Livre Docente Paulo Albertini Instituição: Instituto de Psicologia – Universidade de São Paulo (IP/USP) Julgamento: ________________________________________________ Prof. Doutor Marco Aurélio de Lima Instituição: Escola Superior de -

Stockholm and Eurovison Song Contest

Stockholm and Eurovison Song Contest Two Eurovision entries in 2015 were written during Stockholm Songwriting Camp Macedonia’s ”Autumn Leave’s” was composed and written by Joacim Persson. Azerbaijan’s ”Hour of the Wolf” was written by Nicolas Rebscher, Nicklas Lif and Lina Hansson during the first ever Stockholm Songwriting Camp at Pop House hotel in Stockholm, january 2015. In addition several pop songs met the public ears during the year, including Conchita Wurst’s ”Firestorm” written and produced by Joacim Persson, Sebastian Arman and Aleena Gibson (who was an additional writer not at the camp), and the song ‘Step to my beat’ which the ‘pop dynamo’ Ronika co-wrote at the camp with Nicolas Rebscher. It was also featured in The Guardians pop playlist. Stockholm Songwriting Camp is an initiative that brings together writers and producers from around the world. It is a hub that values the creativity of others and wants to provide a neutral platform for embracing creativity across the songwriting world. What makes the concept different from a lot of camps is the fact that the organizers do not claim any publishing rights, all property is the writers – it is simply the meeting place. The concept was founded by Niclas Molinder owner of Auddly, based in Stockholm. The second Stockholm Songwriting Camp takes place 5th – 8th February 2016 www.stockholmsongwritingcamp.com Source: Stockholm Business Region/Stockholm Songwriting Camp The City of Stockholm www.visitstockholm.com Follow @esc16stockholm on twitter Follow @visitstockholm on facebook, twitter and instagram Images and stockshots: mediabank.visitstockholm.com Follow @investstockholm on twitter youtube.com/stockholm Facts about Stockholm and Eurovision Song Contest 43 countries will be competing during Eurovision Song Contest in Stockholm, May 10-14, 2016 at Stockholm Globe Arena. -

Mamma Mia Medley! Mamma Mia – the Film!

ABBA! Mamma Mia Medley! Mamma Mia – The Film! The film Mamma Mia was made in 2008 and is classed as a ‘Jukebox Musical’. A jukebox musical is a film or musical where the story is based around songs written by one particular song or band. For this musical film, all the music was created by the band ABBA! Can you think of any other films or musicals that would be a jukebox musical? Mamma Mia Medley In this piece there are 3 songs… Mamma Mia Waterloo Dancing Queen Mamma Mia Challenge For your first challenge, find out the following facts about the 3 songs in our medley…. When was the song written? Did it place in the charts? If so, what number did it get to? Who wrote the song? Was it all the band or just certain members? ABBA! ABBA were a Swedish pop group formed in Stockholm in 1972! Famously the group’s name is an acronym of the first letters of their first names. What would your band name be if you used all the first names in your family? They first came to fame in 1974, when they won the Eurovision Song Contest Eurovision Challenge! ABBA may not have been famous in the 70s if it wasn’t for the Eurovision Song Contest. Your challenge is to find out about some of the most famous winners of the Eurovision Song Contest through its history. Who is your favourite out of the winners you’ve heard? Why? The Songs! There is usually a story or a background to pop songs, and that’s no different for our 3 ABBA songs.