An Analysis of the Attribution of the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Destructive Pigment Characterization

Looking for common fingerprints in Leonardo’s pupils through non- destructive pigment characterization LETIZIA BONIZZONI 1*, MARCO GARGANO 1, NICOLA LUDWIG 1, MARCO MARTINI 2, ANNA GALLI 2, 3 1 Dipartimento di Fisica, Università degli Studi di Milano, , via Celoria 16, 20133 Milano (Italy) 2 Dipartimento di Scienza dei Materiali, Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca, via R. Cozzi 55, 20125 Milano (Italy) and INFN, Sezione Milano-Bicocca. 3 CNR-IFN,piazza L. da Vinci, 20132 Milano (Italy). *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Non-invasive, portable analytical techniques are becoming increasingly widespread for the study and conservation in the field of cultural heritage, proving that a good data handling, supported by a deep knowledge of the techniques themselves, and the right synergy can give surprisingly substantial results when using portable but reliable instrumentation. In this work, pigment characterization was carried out on twenty-one Leonardesque paintings applying in situ XRF and FORS analyses. In-depth data evaluation allowed to get information on the colour palette and the painting technique of the different authors and workshops. Particular attention was paid to green pigments (for which a deeper study of possible pigments and alterations was performed with FORS analyses), flesh tones (for which a comparison with available data from cross sections was made) and ground preparation. Keywords pXRF, FORS, pigments, Leonardo’s workshop, Italian Renaissance INTRODUCTION “Tristo è quel discepolo che non ava[n]za il suo maestro” - Poor is the pupil who does not surpass his master - Leonardo da Vinci, Libro di Pittura, about 1493 1. 1 The influence of Leonardo on his peers during his activity in Milan (1482-1499 and 1506/8-1512/3) has been deep and a multitude of painters is grouped under the name of leonardeschi , but it is necessary to distinguish between his direct pupils and those who adopted his manner, fascinated by his works even outside his circle. -

Wliery Lt News Release Fourth Street at Constitution Avenue Nw Washington Dc 20565 • 737-4215/842-6353

TI ATE WLIERY LT NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215/842-6353 PRESS PREVIEW AUGUST 9, 1984 10:00 A.M. - 1:00 P.M. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RENAISSANCE DRAWINGS FROM THE AMBROSIANA AT NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. JULY 27, 1984. The Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, one of Europe's most prestigious research libraries, houses an impressive collection of manuscripts, printed books, and drawings. From the approximately 12,000 drawings in the Ambrosiana collection, eighty-seven sheets from the late fourteenth to early seventeenth centuries will go on view in the National Gallery of Art's West Building beginning August 12, 1984 and running through October 7, 1984. The Ambrosiana collection contains some of the finest works of North Italian draftsmanship. Until recently, these drawings (with the exception of those of the Venetian School) have received little attention from scholars outside Italy. This exhibition brings to the United States for the first time works from the Biblioteca Ambrosiana by prominent artists of the North Italian Schools as well as by major artists of the Renaissance in Italy and Northern Europe. The show includes works by Pisanello, Leonardo, Giulio Romano, Vasari, Durer, Barocci, Bans Holbein the Elder and Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Some of the earliest drawings in the exhibition are by the masters of the International Gothic Style. Several drawings by the prolific (MORE) RENAISSANCE DRAWINGS FRCM THE AMBROSIANA -2. draftsman, Pisanello, appear in the shew. Figures in elegant and fashionable costumes are depicted in his Eleven Men in Contemporary Dress. -

Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514-16) in the Context of Il Cortegiano

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Paragon/Paragone: Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514-16) in the Context of Il Cortegiano Margaret Ann Southwick Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1547 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O Margaret Ann Southwick 2005 All Rights Reserved PARAGONIPARAGONE: RAPHAEL'S PORTRAIT OF BALDASSARE CASTIGLIONE (1 5 14-16) IN THE CONTEXT OF IL CORTEGIANO A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Cornmonwealtli University. MARGARET ANN SOUTHWICK M.S.L.S., The Catholic University of America, 1974 B.A., Caldwell College, 1968 Director: Dr. Fredrika Jacobs Professor, Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December 2005 Acknowledgenients I would like to thank the faculty of the Department of Art History for their encouragement in pursuit of my dream, especially: Dr. Fredrika Jacobs, Director of my thesis, who helped to clarify both my thoughts and my writing; Dr. Michael Schreffler, my reader, in whose classroom I first learned to "do" art history; and, Dr. Eric Garberson, Director of Graduate Studies, who talked me out of writer's block and into action. -

The Pear-Shaped Salvator Mundi Things Have Gone Very Badly Pear-Shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi

AiA Art News-service The pear-shaped Salvator Mundi Things have gone very badly pear-shaped for the Louvre Abu Dhabi Salvator Mundi. It took thirteen years to discover from whom and where the now much-restored painting had been bought in 2005. And it has now taken a full year for admission to emerge that the most expensive painting in the world dare not show its face; that this painting has been in hiding since sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017 for $450 million. Further, key supporters of the picture are now falling out and moves may be afoot to condemn the restoration in order to protect the controversial Leonardo ascription. Above, Fig. 1: the Salvator Mundi in 2008 when part-restored and about to be taken by one of the dealer-owners, Robert Simon (featured) to the National Gallery, London, for a confidential viewing by a select group of Leonardo experts. Above, Fig. 2: The Salvator Mundi, as it appeared when sold at Christie’s, New York, on 15 November 2017. THE SECOND SALVATOR MUNDI MYSTERY The New York arts blogger Lee Rosenbaum (aka CultureGrrl) has performed great service by “Joining the many reporters who have tried to learn about the painting’s current status”. Rosenbaum lodged a pile of awkwardly direct inquiries; gained a remarkably frank and detailed response from the Salvator Mundi’s restorer, Dianne Dwyer Modestini; and drew a thunderous collection of non-disclosures from everyone else. A full year after the most expensive painting in the world was sold, no one will say where it has been/is or when, if ever, it might next be seen. -

Leonardo Da Vinci’ of Milan

SISSA – International School for Advanced Studies Journal of Science Communication ISSN 1824 – 2049 http://jcom.sissa.it/ Comment SCIENCE CENTRES AROUND THE WORLD SEE UNREST FOR ART AND SCIENCE IN SOCIETY Arts and science under the sign of Leonardo. The case of the National Museum of Science and Technology ‘Leonardo da Vinci’ of Milan Claudio Giorgione ABSTRACT: Drawing on the example of Leonardo da Vinci, who was able to combine arts and science in his work, the National Museum of Science and Technology of Milan has always pursued the blending and the dialogue of humanistic and scientific knowledge. It has employed this approach in all of its activities, from the set design of exhibition departments to the acquisition of collections and, more recently, in the dialogue with the public. Now more than ever, following a renewal path for the Museum, these guidelines are being subject to research to achieve a new and more up-to-date interpretation. When Guido Ucelli, a Milanese industrialist and the founder of the Museum in 1953, launched the strategic development plan for this Institution, he had a very clear vision from the outset: a modern Museum of Science that could overcome the traditional division between scientific knowledge and humanistic culture and that should have been able to let Arts and Science dialogue, live together and complement each other. This is why the figure of Leonardo was and is still today an evident case of merger of different knowledge, immediately become the leading theme of the Museum. The Gallery exhibiting the models of the machines built in 1953 based on the interpretation of his designs displays real artistic handicraft items, not only technical-didactic creations. -

BERNARDINO LUINI Catalogo Generale Delle Opere

CRISTINA QUATTRINI BERNARDINO LUINI Catalogo generale delle opere ALLEMANDI Sommario Abbreviazioni 7 1. Fortune e sfortune di Bernardino Luini 27 2. La questione degli esordi ALPE Archivio dei Luoghi Pii Elemosinieri, Milano, Azienda di Servizi alla Persona «Golgi-Redaelli» e del soggiorno in Veneto AOMMi Archivio dell’Ospedale Maggiore di Milano 35 3. Milano nel secondo decennio APOFMTo Archivio della Curia Provinciale OFM di Torino del Cinquecento ASAB Archivio Storico dell’Accademia di Brera di Milano ASBo Archivio di Stato di Bobbio 61 4. Le grandi commissioni ASCAMi Archivio Storico della Curia Arcivescovile di Milano degli anni 1519-1525 ASCMi Archivio Storico Civico di Milano 77 5. 1525-1532. Gli ultimi anni ASCo Archivio di Stato di Como ASDCo Archivio Storico Diocesano di Como ASMi Archivio di Stato di Milano 89 Tavole ASMLe Archivio di San Magno a Legnano, Milano ASS Archivio Storico del Santuario di Saronno, Varese Le opere ASTi Archivio di Stato del Cantone Ticino, Lugano 125 Dipinti IAMA Istituto di Assistenza Minori e Anziani di Milano Sopr. BSAE Mi Ex Soprintendenza per i Beni storici artistici ed etnoantropologici per le province 413 Dipinti dubbi, irreperibili o espunti di Milano, Bergamo, Como, Lecco, Lodi, Monza e Brianza, Pavia, Sondrio e Varese, 421 Alcune copie da originali perduti ora Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per la città metropolitana di Milano e Soprintendenza Archeologia, belle arti e paesaggio per le province di Como, Lecco, e derivazioni da Bernardino Luini Monza-Brianza, Pavia, Monza e Varese. 429 Disegni 465 Opere perdute f. foglio rip. riprodotto 471 Regesto di Bernardino Luini s.d. -

Evidence That Leonardo Da Vinci Had Strabismus

Confidential: Embargoed Until 11:00 am ET, October 18, 2018. Do Not Distribute Research JAMA Ophthalmology | Brief Report Evidence That Leonardo da Vinci Had Strabismus Christopher W. Tyler, PhD, DSc Supplemental content IMPORTANCE Strabismus is a binocular vision disorder characterized by the partial or complete inability to maintain eye alignment on the object that is the target of fixation, usually accompanied by suppression of the deviating eye and consequent 2-dimensional monocular vision. This cue has been used to infer the presence of strabismus in a substantial number of famous artists. OBJECTIVE To provide evidence that Leonardo da Vinci had strabismus. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS In exotropia, the divergent eye alignment is typically manifested as an outward shift in the locations of the pupils within the eyelid aperture. The condition was assessed by fitting circles and ellipses to the pupils, irises, and eyelid apertures images identified as portraits of Leonardo da Vinci and measuring their relative positions. MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Geometric angle of alignment of depicted eyes. RESULTS This study assesses 6 candidate images, including 2 sculptures, 2 oil paintings, and 2 drawings. The mean relative alignments of the pupils in the eyelid apertures (where divergence is indicated by negative numbers) showed estimates of −13.2° in David,−8.6° in Salvator Mundi,−9.1° in Young John the Baptist,−12.5° in Young Warrior, 5.9° in Vitruvian Man, and −8.3° in an elderly self-portrait. These findings are consistent with exotropia (t5 = 2.69; P = .04, 2-tailed). Author Affiliation: Division of Optometry and Vision Sciences, School of Health Sciences, City CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE The weight of converging evidence leads to the suggestion University of London, London, that da Vinci had intermittent exotropia with the resulting ability to switch to monocular United Kingdom. -

Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci: Beauty. Politics, Literature and Art in Early Renaissance Florence

! ! ! ! ! ! ! SIMONETTA CATTANEO VESPUCCI: BEAUTY, POLITICS, LITERATURE AND ART IN EARLY RENAISSANCE FLORENCE ! by ! JUDITH RACHEL ALLAN ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT ! My thesis offers the first full exploration of the literature and art associated with the Genoese noblewoman Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci (1453-1476). Simonetta has gone down in legend as a model of Sandro Botticelli, and most scholarly discussions of her significance are principally concerned with either proving or disproving this theory. My point of departure, rather, is the series of vernacular poems that were written about Simonetta just before and shortly after her early death. I use them to tell a new story, that of the transformation of the historical monna Simonetta into a cultural icon, a literary and visual construct who served the political, aesthetic and pecuniary agendas of her poets and artists. -

A Double Leonardo. on Two Exhibitions (And Their Catalogues) in London and Paris;:'

Originalveröffentlichung in: Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 76 (2013), S. 417-427 A usstellungsbesprechung A double Leonardo. On two exhibitions (and their catalogues) in London and Paris;:' Luke Syson/Larry Keith (ed.), Leonardo da Vinci: Painter at the Court of Milan, London: National Gallery, 2011, 319 pages, ills., £29, ISBN 978-1-85709-491-6 / Vincent Delieuvin (ed.), La Sainte Anne. L’ultime chef-d ’ceuvre de Leonard de Vinci, Paris: Louvre, 2012, 443 pages, ills., €45, ISBN 978-2-35031-370-2 Ten or twenty years ago, the idea that two major insights into individual works from the circle of exhibitions with drawings and several original Leonardo ’s pupils, and these findings are careful- paintings by Leonardo da Vinci could open within ly compiled and discussed in the catalogue. We just a few months of each other, would have been are unlikely to come face to face again with such considered impossible. But this is exactly what the an impressive number of first-rate and in most London National Gallery and the Paris Louvre re- cases well-restored paintings by artists such as cently managed to do. First came Leonardo da Ambrogio de Predis, Giovanni Antonio Boltraf- Vinci. Painter at the Court of Milan, which opened fio and Marco d’Oggiono. More problematic, on in November 2011 in London. The National the other hand, are some of the attributions, dat- Gallery ’s decision to host what proved to be the ings and interpretations proposed in the catalogue largest and most important exhibition of original and concerning the works by Leonardo himself. -

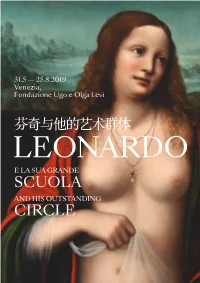

Scuola Circle 芬奇与他的艺术群体

31.5 — 25.8.2019 Venezia, Fondazione Ugo e Olga Levi 芬奇与他的艺术群体 E LA SUA GRANDE SCUOLA AND HIS OUTSTANDING CIRCLE 31.5 — 25.8.2019 Venezia, Fondazione Ugo e Olga Levi 芬奇与他的艺术群体 E LA SUA GRANDE SCUOLA AND HIS OUTSTANDING CIRCLE A cura di | Curator | 展览策展人 Nicola Barbatelli 尼古拉·巴尔巴泰利 Nota introduttiva di | Introduced by | 序言 Giovanna Nepi Scirè 乔凡娜·内皮·希雷 LEONARDO LEONARDO E LA SUA GRANDE SCUOLA AND HIS OUTSTANDING CIRCLE Palazzo Giustinian Lolin ospita fino al 25 agosto 2019 un importante tributo al genio Palazzo Giustinian Lolin hosts until 25 August 2019 an important tribute to the genius of di Leonardo Da Vinci, in occasione delle celebrazioni del cinquecentenario dalla Leonardo Da Vinci, on the occasion of the celebrations marking the 500th anniversary of scomparsa: la mostra “Leonardo e la sua grande scuola”, a cura di Nicola Barbatelli. Leonardo da Vinci’s death: the exhibition “Leonardo and His Outstanding Circle”, curated by Con 25 opere esposte – di cui due disegni attribuiti al genio toscano – il progetto pone Nicola Barbatelli. Proposing a collection of 25 works — among which two drawings attributed l’accento non solo sull’opera del grande Maestro, ma soprattutto sulle straordinarie to the Tuscan genius —, this project does not merely focus on the work of the great master, pitture dei suoi seguaci – tra cui Giampietrino, Marco d’Oggiono, Cesare da Sesto, but above all on the extraordinary paintings of his followers — including Giampietrino, Marco Salaì, Bernardino Luini – e il loro dialogo con la poetica artistica di Leonardo. d’Oggiono, Cesare da Sesto, Salaì, Bernardino Luini — and their dialogue with Leonardo’s artistic poetics. -

A Study of the Soul in Recent Poetics

ROSE OF T!jE WORLD A STUDY OF THE SOUL IN A RECENT POETICS Jchn William Scoggan B.Sc. Carleton University, Ottawa, 1968 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of E.nglish @ JOHN WILLIAM SCOGGAN 1973 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July, 1973 VOLUME I APPROVAL Name : John Scoggan Degree: Master of Arts Title of Thesis: Charles Olson's Imago Mundi Eramini ng Committee: Chairman: Dr. S .A. Black ~ar~hMaud Senior Supervisor Robin Blaser Evan Alderson Arthur Stone Assistant Professor Department of Mathematics Simon Fraser University Date Approved: July 25, 1972 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE f hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behaif or for cne nf its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of ~hesis /~issertation : Rose of the World: a study of the soul in a recent poetics Author- : John William Scoggan (name ) December 11, 1973 ABSTRACT This thesis is about the Gold Flower which has always stood for the sources of the human soul. -

Niccolò Di Pietro Gerini's 'Baptism Altarpiece'

National Gallery Technical Bulletin volume 33 National Gallery Company London Distributed by Yale University Press This edition of the Technical Bulletin has been funded by the American Friends of the National Gallery, London with a generous donation from Mrs Charles Wrightsman Series editor: Ashok Roy Photographic credits © National Gallery Company Limited 2012 All photographs reproduced in this Bulletin are © The National Gallery, London unless credited otherwise below. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including CHICAGO photocopy, recording, or any storage and retrieval system, without The Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence: prior permission in writing from the publisher. fi g. 9, p. 77. Articles published online on the National Gallery website FLORENCE may be downloaded for private study only. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence © Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library: fi g. 45, p. 45; © 2012. Photo Scala, First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Florence – courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali: fig. 43, p. 44. National Gallery Company Limited St Vincent House, 30 Orange Street LONDON London WC2H 7HH The British Library, London © The British Library Board: fi g. 15, p. 91. www.nationalgallery. co.uk MUNICH Alte Pinakothek, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, Munich British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record is available from the British Library. © 2012. Photo Scala, Florence/BPK, Bildagentur für Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte, Berlin: fig. 47, p. 46 (centre pinnacle); fi g. 48, p. 46 (centre ISBN: 978 1 85709 549 4 pinnacle).