The Automobile Industry; the Coming of Age Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the Japanese Automotive Industry in Canada

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE JAPANESE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY IN CANADA Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association of Canada A SHORT HISTORY OF THE JAPANESE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY IN CANADA Commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association of Canada 1984 – 2004 Second Edition 2009 CONTENTS 1. Early History of the Canadian Auto Industry . 6 2. Historical Development of the Japanese Auto Industry in Canada . 10 i) In the beginning, circa 1965 ii) 1970’s - Oil ‘shocks’: new demand for small, fuel efficient cars iii) 1980’s - Investments in manufacturing iv) 1990’s - Expansions & growth: vehicles & auto parts v) Into the 21st century – An integral part of the Canadian auto industry vi) The Impact of Japanese Automotive Investment in Canada vii) Canadian auto-related developments in Japan viii) JAMA Canada Chairmen, 1983 – 2008 3. A Collection of Personal Observations on JAMA Canada, Pacific Automotive . 22 Co-operation (PAC) and the Japanese Auto Industry in Canada The Hon. Edward C. Lumley, former Minister of Industry, Trade & Commerce, Government of Canada Barry C. Steers, former Canadian Ambassador to Japan Patrick J. Lavelle, former President, Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association of Canada Morley Bursey, Honourary Executive Director, Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association of Canada Slawek Skorupinski, former Director General, Automotive, Industry Canada Neil de Koker, President, Original Equipment Suppliers Association (OESA), former President, Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association of Canada K. Kawana, former President, Nissan Canada & Chairman, JAMA Canada (1984 – 1986) S. Yoshioka, former Secretary General, JAMA Tokyo & Director, JAMA Canada S. Yanagisawa, former President, Toyota Canada & Chairman, JAMA Canada (1986 – 1989) Y. Nakatani, former President, Toyota Canada & Chairman, JAMA Canada (1996 – 2002) H. -

Historical Marker - L343 - William C

Historical Marker - L343 - William C. Durant / Durant-Dort Carriage Company (Marker ID#:L343) Front - Title/Description William C. Durant William Crapo Durant (1861-1947), one of Flint’s most important historical figures, was a pioneer in the development of the American auto industry. Durant’s vehicle ventures began in 1886, when, with a borrowed fifteen hundred dollars, he bought the rights to build a two-wheeled road cart. Nine years later the Flint Road Cart Company, begun by Durant and his partner, Dallas Dort, became the Durant-Dort Carriage Company. Durant took over Flint’s tiny Buick Motor Company Significant Date: in 1904. He turned it into the largest American Civil War and After (1860-1875) producer of automobiles by 1908, and, on Buick’s Registry Year: 1974 Erected Date: 1978 success, founded General Motors in September of that year. In 1911 he and Louis Chevrolet founded Marker Location the Chevrolet Motor Company, which combined Address: 316 West Water with General Motors seven years later. Parting with General Motors in the 1920s, Durant founded City: Flint Durant Motors Company and its subsidiaries but State: MI ZipCode: went bankrupt during the depression. He died in New York City. County: Genesee Township: Back - Title/Description Lat: 43.01747100 / Long: -83.69526200 Durant-Dort Carriage Company Web URL: William C. Durant and his business partner, J. Dallas Dort, completed this building in 1896. It was originally the headquarters of the Durant-Dort Carriage Company, one of the largest volume producers of horse-drawn vehicles in the United States at the turn of the century. -

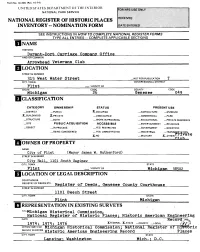

NOMINATION FORM I NAME Durant

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Durant-Dort Carriage Company Office____________ AND/OR COMMON Arrowhead Veterans Club_______________________ LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 315 West Water Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Flint —. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Michigan 26 Genesee 049 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL — TRANSEORTATION, f'T'T' Vfl T A X-NO —MILITARY X_OTHER:rriV<llm iihi ' e OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Flint (Mayor James W. Rutherford) STREET & NUMBER City Hall, 1.101 South Saginaw CITY, TOWN STATE Flint VICINITY OF Michigan U8502 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Registrfir of Deeds» Genesee County Courthouse STREET& NUMBER 1101 Beech Street CITY. TOWN STATE Flint Michigan REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTL1Michigan Historical Commissions National Register of Historic Places; Historic American Engineering DATE Record 1974; 1975; 1976________________XFEDERAL -

DEPENDABILITY Building at a Low Price

' ¦ < I now producing the fhalmers Ms ha| been to mail* the car an outatandluf AROUND THE TOWN value. THE NEW HUDSON SEDAN "UiKtor price condition* that hay* LEXINGTONCAR prevailed for the past year, the valu« SPOUTMODELS C. W. Mlnker, Washington dis¬ of the Chalmers haa been very pro YET PRACTICAL, ' tributor for the Columbia six, gave LUXURIOUS nounced. an Informal dinner to the member* "But the new price puts It praotla ally In a claaa by Itaelf. It la tt* of his organization and several loweat price that haa ever beei HERETOREIN Washington business men Wednes¬ placed on a oar at all to be compare* day evening at his Fourteenth street with the Chalmera Six. showroom. The event marked the "The Chalmers haa been developed : completion of the first six months greatly in the past year and In ij of Mr. Winkers distributorship which- KaffiQKi)PP P-BRm4 six-cylinder pnnslbllltlee have bee* ASSERTSKEMP needless to say has been a profitable flKsli brought to new heights of perform one to him and the Columbia Six. BfiS Reduction Is Most anoe. Auburn Auto Pr«»id«nt Be¬ Those attending were: C. W. Mlnker, fc An.ted- Unhesitatingly Pre¬ Leary Says "This coupled with Its extraordln John B. Cochran, president of the Important in Rscent ary goof looks have won It an eves eves Rakish Cart Will Ba Franklin National Bank; Qeorite E. isopt, sents Program for widening circle of admirers. Standard. Sullivan, attorney; D. B. Oolver, W. 1923. Pries Changes. "The n<*w price makea it avaflabh Bond, Louis Hoover. William Loetcli, to a still greater number of peoplt Walter Blake. -

On the Morning of Thursday, January 14, 1926 Fire Broke out in The

Found on Ancestry.com (Author Unknown) On the morning of Thursday, January 14, 1926 fire broke out in the company’s sanding machine and spread spontaneously through the blowers to different parts of the room. In the few hours that followed, Onaway’s main means of livelihood went up in smoke and although the city still exists, it has never reached the proportion it was on that historical day. With the presence of the American Wood Rim Co. and its sister company, the Lobdell Emerey Manufacturing Co., Onaway experienced tremendous growth in its early year. The big industry, along with the profitable timber business made Onaway the biggest little town in northern Michigan. According to one report, Onaway had two newspapers, three lawyers, four doctors, three large hotels, 17 saloons, nine churches, two bakeries, a fairgrounds, racetrack and an opera house in the pre-fire days. The figure varies, but Onaway’s population was approximately 4,000 and the two huge industries employed anywhere from 1200 to 1500 persons. The Lobdell Emery Manufacturing co. was involved in lumbering, sawmill operations and the making of such products as dowels, broom handles, and coat hanger stock. The American Wood Rim Co., was the world’s largest and finest producer of automobile steering wheels and bicycle rims. For a number of years the company made all the steering wheels with either malleable iron or aluminum spiders. The alumi- num spiders were all molded and finished in the plant while the malleable iron castings were purchased from outside sour- ces. During its last few years in Onaway, the American Wood Rim Co. -

1St Responder Newspaper

Title Subtitle Frequency Dates Became Less than 5 Issues? 1st Responder Newspaper New Jersey Edition Oct 2004 x 1st Responder Newspaper Ohio/Pennsylvania Edition May 1999 x 4 Wheel & Off-Road Dec 1979 - Apr 1995 x 9N-2N-8N Newsletter Ford Tractors Jan 1988 - Oct 1997 A.A.H.C. Newsletter April 1990 – July 1993 AAA World 6x/yr May/June 1981 – Jan/Feb 1995 AACA Judges Newsletter 3x/yr Dec 1966 - Jan 1989 AAM News Automobile Association of Malaysia Monthly Dec. 1967 – December 1984 DRIVE Abarth Register, USA The Stinger Quarterly Summer 1978 – July 2004 Abbey Newsletter Bookbinding & Conservation Feb 1984 - Dec 1984 Accelerator Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Museum Accelerator McLaughlin Buick Club of Canada Bimonthly Jan 1972- Present Access Research at the Univ. of Calif. Transportation Center Fall 1993 - Present Accessory & Garage Journal Incomplete 1912-1920 Action '88 Pub. For Lincoln-Mercury Sales Professionals Jul 1988 x Action Era Vehicle Bimonthly Sep/Oct 1967 – Apr/Jun 2001 Action Track Pontiac Aug 1987 - Apr 1991 x Acura Quarterly July 1987 - Apr 1988 x AD&D Automotive Design & Development Monthly Mar 1978-Jun 1978 x ADAC (German) Jul 1986 x Advertising Requirements Oct 1957 x AERO America's Aviation Weekly Apr 1911 x AFAS Quarterly Automotive Fine Arts Society Quarterly Winter 1989 – 2004 AFV Alternative Fuel Vehicle Report (Ford Motor Co.) Jan 1991 - Aug 1991 x Ahrens-Fox Bulletin Air Cooled News H.H. Franklin Club 3x/yr Mar 1968 – Present Airflow Newsletter Airflow Club of America Monthly Oct. 1963 – Sept 1993 Alarm Room News Sep 1983 -

Marque Club Web Address National Clubs

Marque Club Web Address National Clubs ACD Auburn Cord Duesenberg Club www.acdclub.org AACA Antique Automobile Club of America www.aaca.org BMW BMW Car Club of America www.bmwcca.org CCCA Classic Car Club of America [email protected] CCA Corvette Club of America, www.vette-club.org FCA Ferrari Club of America www.ferrariclubofamerica.org GOOD-GUYS Good-Guys Hotrod Association www.good-guys.com HCCA Horseless Carriage Club of America www.hcca.org HHRA National Hotrod Association www.nhra.com MBCA Mercedes-Benz Club of America www.mbca.org MCA Mustang Club of America www.mustang.org NMCA National Muscle Car Association www.nmcadigital.com NSRA National Street Rod Association www.nsra-usa.com PCA Porsche Club of America www.pca.org RROC Rolls-Royce Owners Club www.rroc.org SCCA Sportscar Club of America www.scca.com SVRA Sportscar Vintage Racing Association www.svra.org VMCCA Veteran Motor Car Club Of America www.vmcca.org VCCA Vintage Car Club of American www.soilvcca.com VMC Vintage Motorsports Council www.the-vmc.com VSCCA Vintage Sports Car Club of America www.vscca.org VCA Volkswagen Club of America www.vwclub.org SINGLE MARQUE: AUTOS AC AC Owners Club http://acowners.club ALFA ROMEO Alfa Romeo Owners Club http://www.aroc-usa.org ALLARD Allard Owners Club www.allardownersclub.org ALVIS North American Alvis Owners Club http://www.alvisoc.org AMC American Motors Owners Association www.amonational.com AMERICAN AUSTIN/BANTAM American Austin/Bantam Club www.austinbantamclub.com AMPHICAR International Amphicar Owners Club www.amphicar.com AUBURN/CORD/DUESENBERG Auburn Cord Duesenberg Club http://www.acdclub.org AUSTIN-HEALEY Austin-Healey Club of America http://www.healeyclub.org AVANTI Avanti Owners Association International, www.aoai.org BRICKLIN Bricklin International Owners Club www.bricklin.org BUGATTI American Bugatti Club, http://www.americanbugatticlub.org BUICK Buick Club of America www.buickclub.org CADILLAC Cadillac and LaSalle Club, www.cadillaclasalleclub.org CHECKER Checker Car Club of America www.checkerworld.org CHEVROLET American Camaro Assoc. -

Inside Speeding, Manslaughter, Stealing Cars

ourna The Society of Automotive Historians, Inc. Issue 212 September-October 2004 The Motor Bandits: 5 Cars, Crimes and Philosophy by Michael Bromley www.autohistory.org \aiming a first is a dangerous business, especially with automobiles. You never reall y know. So get out your pen and co rrect me on this one: the first time an C automobile was used for non-automotive crime was in ew York City in 1910. Inside Speeding, manslaughter, stealing cars ... these thrills were earlier perfected. lt wasn't until 1910 that professional criminals and gangs took to the automobile. My coll ection of Editorial Comment 2 New York Tim es articles gives the first as eptember 29, 1910 with "Fight Pistol Battle in Speeding Autos." These were not chauffeurs of rival steel magnates. Okay, before the ded icated refuters out there find some 1903 Kalamazoo bank heist with a getaway in a President's Perspective 3 curved dash Olds (ca lling Keith Marvin! calling Keith Marvin!), allow me a few thoughts on why 1910 marks the meeting of automobiles and professional crime. Anything before was isolated, and not ge nerally happening, for the si mple reason SAH News 4 that before 1910 thugs in cars would have been conspicuous. Thanks to the motoring President-my man William Howard Taft-automobiles in 1910 were normal, political Obituary 6 ly-correct and socially-acceptable objects of what Alexis de Tocqueville called every Merle "Mickey" Mishne American's glance of hope and envy on the enjoyments of the rich. Before Taft, automo biles were hateful envy-and anger and calls for the income tax and six m.p.h. -

Mitrray P Ex Ad

1 TOWGBT GLOBE '.' TONIGHT 1 !lì t--j Dr Tloss office will clnsed be (lawn is depicted from October 3 to October 27. A eiil's great atlventure between dawn and Advrrtisement. 84-O- ct 27 amaziiiglv in BOiìEUT '.. LEO.VARD'S presentation of Mrs. B. E. Doyle has returned from Boston where she has been taking special tiaining under Mrs. MAE Lilla Viles Wyman in modem training of children, also in ali the Fiotti Investors Guaio, Ausrust, 1!)22 modem lanees. Arsene Gicnier loft Thursday for New York city where he has MI TRRAY (Continued Doni Caledonian of Sat., Oct. 14) the outstanding stock of the various divisionai com- takon a position with an automo- The two Durant cars have a bijf field aboard as well panies into the parent corporation' shares between bile concern. IVs ioasted. This as at home, inasmuch as foreijrn as well as domestic August 1, 1924, and August 1, 1920, on bases of $:!() to Miss Khea C. Gilson, a teachor extra process $40 i ; ha re for Durant Motors, Inc., stock. one users aie appreciative of automobiles of merit at . righi in the schools of Springfield, this to-da- y y q detightful priees. Althou;h there aie in the world approx-ìmatcl- For example, the holders of the stock of the Durant state was in St. Johnsbury last gives 12,1)00,000 ?asoline-piopelle- d vehicles, mpie than Motor Company of Indiana, Inc., of whose .'100,000 shares, week to attend the teachers' con- quality that can 10,000,000 of these vehicles are in the United States and having a par value of $10, 240,000 shares have been au- vention and remained until Sunday not be duplicateci tlie remaininp 2,000,000 scatterei! ali over the world. -

The Fable of Fisher Body Revisited. (Pdf)

The Fable of Fisher Body Revisited Ramon Casadesus-Masanell Daniel Spulber Working Paper 10-081 Copyright © 2010 by Ramon Casadesus-Masanell and Daniel Spulber Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. The Fable of Fisher Body Revisited Ramon Casadesus-Masanell and Daniel Spulber* July 2000 ____________________________ *Harvard Business School Morgan Hall 231, Soldiers Field, Boston, Massachusetts 02163 and Kellogg Graduate School of Management, Northwestern University, 2001 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL, 60208. Introduction It is difficult to hit a moving target. Benjamin Klein (2000) essentially presents a new Fisher Body story despite his contention that “the facts of the Fisher-GM case are shown to be fully consistent with the hold up description provided in Klein, Crawford, and Alchian.” Klein (2000) concedes many of the points made in the articles by Ronald Coase (2000), Robert Freeland (2000) and Ramon Casadesus-Masanell and Daniel F. Spulber (2000). Contrary to Klein et al. (1978), Klein (2000) now acknowledges that the main economic force behind the merger was the need for coordination: “As body design became more important and more interrelated with chassis design and production, the amount of coordination required between a body supplier and its automobile manufacturer customer increased substantially. [...] These economic forces connected with annual model changes ultimately led all automobile manufacturers to adopt vertical integration.” Despite having made this important admission, Klein creates a new fable: the Flint plant problem. -

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators”

Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators” Transportationthehenryford.org in America/education Table of Contents PART 1 PART 2 03 Chapter 1 85 Chapter 1 What Is “American” about American Transportation? 20th-Century Migration and Immigration 06 Chapter 2 92 Chapter 2 Government‘s Role in the Development of Immigration Stories American Transportation 99 Chapter 3 10 Chapter 3 The Great Migration Personal, Public and Commercial Transportation 107 Bibliography 17 Chapter 4 Modes of Transportation 17 Horse-Drawn Vehicles PART 3 30 Railroad 36 Aviation 101 Chapter 1 40 Automobiles Pleasure Travel 40 From the User’s Point of View 124 Bibliography 50 The American Automobile Industry, 1805-2010 60 Auto Issues Today Globalization, Powering Cars of the Future, Vehicles and the Environment, and Modern Manufacturing © 2011 The Henry Ford. This content is offered for personal and educa- 74 Chapter 5 tional use through an “Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike” Creative Transportation Networks Commons. If you have questions or feedback regarding these materials, please contact [email protected]. 81 Bibliography 2 Transportation: Past, Present and Future | “From the Curators” thehenryford.org/education PART 1 Chapter 1 What Is “American” About American Transportation? A society’s transportation system reflects the society’s values, Large cities like Cincinnati and smaller ones like Flint, attitudes, aspirations, resources and physical environment. Michigan, and Mifflinburg, Pennsylvania, turned them out Some of the best examples of uniquely American transporta- by the thousands, often utilizing special-purpose woodwork- tion stories involve: ing machines from the burgeoning American machinery industry. By 1900, buggy makers were turning out over • The American attitude toward individual freedom 500,000 each year, and Sears, Roebuck was selling them for • The American “culture of haste” under $25. -

The Story of a Global Brand A. Louis Chevrolet and the Legend Of

Chevrolet – the Story of a Global Brand A. Louis Chevrolet and the Legend of Beaune Like many inventors and pioneers, Louis Chevrolet (1878-1941), the racing driver and automobile designer, represents a challenge for any historian or biographer. Myths and legends surround him and his life. Numerous anecdotes have been told about his career. Today, it has become very difficult to differentiate between fact and fiction. Chevrolet's childhood and youth are well documented. In 1878, he was born on Christmas day in the town of La Chaux-de- Fonds in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. He spent his early childhood nearby in the sleepy little village of Bonfol. Even today, Bonfol remains a small town where the only reminder of its famous son is a memorial plaque on Place Louis Chevrolet. When Louis was nine years old, his family moved to Beaune in Baby Louis Chevrolet France. There, Louis' father owned a watch store, but the venture was not successful. As a result, Louis started working at the age of eleven to support his family. He found employment in the Robin bicycle workshop, where he learned the fundamentals of mechanics. He repaired coaches and bicycles, until one day he was sent to the "Hôtel de la Poste" to repair a steam-driven tricycle belonging to an American. This must have been the moment when Chevrolet fell in love twice. He fell in love with automobiles, and also with the idea of emigrating to America. The American, whose tricycle Chevrolet had skillfully repaired was none other than the multimillionaire Vanderbilt.