The Fable of Fisher Body Revisited. (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the Japanese Automotive Industry in Canada

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE JAPANESE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY IN CANADA Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association of Canada A SHORT HISTORY OF THE JAPANESE AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY IN CANADA Commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association of Canada 1984 – 2004 Second Edition 2009 CONTENTS 1. Early History of the Canadian Auto Industry . 6 2. Historical Development of the Japanese Auto Industry in Canada . 10 i) In the beginning, circa 1965 ii) 1970’s - Oil ‘shocks’: new demand for small, fuel efficient cars iii) 1980’s - Investments in manufacturing iv) 1990’s - Expansions & growth: vehicles & auto parts v) Into the 21st century – An integral part of the Canadian auto industry vi) The Impact of Japanese Automotive Investment in Canada vii) Canadian auto-related developments in Japan viii) JAMA Canada Chairmen, 1983 – 2008 3. A Collection of Personal Observations on JAMA Canada, Pacific Automotive . 22 Co-operation (PAC) and the Japanese Auto Industry in Canada The Hon. Edward C. Lumley, former Minister of Industry, Trade & Commerce, Government of Canada Barry C. Steers, former Canadian Ambassador to Japan Patrick J. Lavelle, former President, Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association of Canada Morley Bursey, Honourary Executive Director, Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association of Canada Slawek Skorupinski, former Director General, Automotive, Industry Canada Neil de Koker, President, Original Equipment Suppliers Association (OESA), former President, Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association of Canada K. Kawana, former President, Nissan Canada & Chairman, JAMA Canada (1984 – 1986) S. Yoshioka, former Secretary General, JAMA Tokyo & Director, JAMA Canada S. Yanagisawa, former President, Toyota Canada & Chairman, JAMA Canada (1986 – 1989) Y. Nakatani, former President, Toyota Canada & Chairman, JAMA Canada (1996 – 2002) H. -

Historical Marker - L343 - William C

Historical Marker - L343 - William C. Durant / Durant-Dort Carriage Company (Marker ID#:L343) Front - Title/Description William C. Durant William Crapo Durant (1861-1947), one of Flint’s most important historical figures, was a pioneer in the development of the American auto industry. Durant’s vehicle ventures began in 1886, when, with a borrowed fifteen hundred dollars, he bought the rights to build a two-wheeled road cart. Nine years later the Flint Road Cart Company, begun by Durant and his partner, Dallas Dort, became the Durant-Dort Carriage Company. Durant took over Flint’s tiny Buick Motor Company Significant Date: in 1904. He turned it into the largest American Civil War and After (1860-1875) producer of automobiles by 1908, and, on Buick’s Registry Year: 1974 Erected Date: 1978 success, founded General Motors in September of that year. In 1911 he and Louis Chevrolet founded Marker Location the Chevrolet Motor Company, which combined Address: 316 West Water with General Motors seven years later. Parting with General Motors in the 1920s, Durant founded City: Flint Durant Motors Company and its subsidiaries but State: MI ZipCode: went bankrupt during the depression. He died in New York City. County: Genesee Township: Back - Title/Description Lat: 43.01747100 / Long: -83.69526200 Durant-Dort Carriage Company Web URL: William C. Durant and his business partner, J. Dallas Dort, completed this building in 1896. It was originally the headquarters of the Durant-Dort Carriage Company, one of the largest volume producers of horse-drawn vehicles in the United States at the turn of the century. -

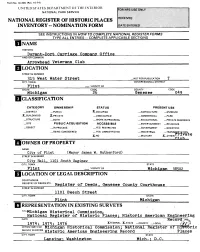

NOMINATION FORM I NAME Durant

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Durant-Dort Carriage Company Office____________ AND/OR COMMON Arrowhead Veterans Club_______________________ LOCATION STREET& NUMBER 315 West Water Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Flint —. VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Michigan 26 Genesee 049 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) X.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL — TRANSEORTATION, f'T'T' Vfl T A X-NO —MILITARY X_OTHER:rriV<llm iihi ' e OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Flint (Mayor James W. Rutherford) STREET & NUMBER City Hall, 1.101 South Saginaw CITY, TOWN STATE Flint VICINITY OF Michigan U8502 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Registrfir of Deeds» Genesee County Courthouse STREET& NUMBER 1101 Beech Street CITY. TOWN STATE Flint Michigan REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TiTL1Michigan Historical Commissions National Register of Historic Places; Historic American Engineering DATE Record 1974; 1975; 1976________________XFEDERAL -

DEPENDABILITY Building at a Low Price

' ¦ < I now producing the fhalmers Ms ha| been to mail* the car an outatandluf AROUND THE TOWN value. THE NEW HUDSON SEDAN "UiKtor price condition* that hay* LEXINGTONCAR prevailed for the past year, the valu« SPOUTMODELS C. W. Mlnker, Washington dis¬ of the Chalmers haa been very pro YET PRACTICAL, ' tributor for the Columbia six, gave LUXURIOUS nounced. an Informal dinner to the member* "But the new price puts It praotla ally In a claaa by Itaelf. It la tt* of his organization and several loweat price that haa ever beei HERETOREIN Washington business men Wednes¬ placed on a oar at all to be compare* day evening at his Fourteenth street with the Chalmera Six. showroom. The event marked the "The Chalmers haa been developed : completion of the first six months greatly in the past year and In ij of Mr. Winkers distributorship which- KaffiQKi)PP P-BRm4 six-cylinder pnnslbllltlee have bee* ASSERTSKEMP needless to say has been a profitable flKsli brought to new heights of perform one to him and the Columbia Six. BfiS Reduction Is Most anoe. Auburn Auto Pr«»id«nt Be¬ Those attending were: C. W. Mlnker, fc An.ted- Unhesitatingly Pre¬ Leary Says "This coupled with Its extraordln John B. Cochran, president of the Important in Rscent ary goof looks have won It an eves eves Rakish Cart Will Ba Franklin National Bank; Qeorite E. isopt, sents Program for widening circle of admirers. Standard. Sullivan, attorney; D. B. Oolver, W. 1923. Pries Changes. "The n<*w price makea it avaflabh Bond, Louis Hoover. William Loetcli, to a still greater number of peoplt Walter Blake. -

Gm Livonia Trim Plant in Livonia, Michigan ______10

Repurposing Former Automotive Manufacturing Sites in the Midwest A report on what communities have done to repurpose closed automotive manufacturing sites, and lessons for Midwestern communities for repurposing their own sites. Prepared by: Valerie Sathe Brugeman, MPP Kristin Dziczek, MS, MPP Joshua Cregger, MS Prepared for: The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation June 2012 Repurposing Former Midwestern Automotive Manufacturing Sites A report on what communities have done to repurpose closed automotive manufacturing sites, and lessons for Midwestern communities for repurposing their own sites. Report Prepared for: The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation Report Prepared by: Center for Automotive Research 3005 Boardwalk, Ste. 200 Ann Arbor, MI 48108 Valerie Sathe Brugeman, MPP Kristin Dziczek, MS, MPP Joshua Cregger, MS Repurposing Former Midwestern Automotive Manufacturing Sites Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS _____________________________________________________________ III About the Center for Automotive Research ______________________________________________ iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY _____________________________________________________________ 4 Case Studies ______________________________________________________________________ 5 Key Findings _______________________________________________________________________ 5 INTRODUCTION __________________________________________________________________ 7 METHODOLOGY __________________________________________________________________ 7 GM LIVONIA TRIM PLANT IN LIVONIA, MICHIGAN _______________________________________ -

On the Morning of Thursday, January 14, 1926 Fire Broke out in The

Found on Ancestry.com (Author Unknown) On the morning of Thursday, January 14, 1926 fire broke out in the company’s sanding machine and spread spontaneously through the blowers to different parts of the room. In the few hours that followed, Onaway’s main means of livelihood went up in smoke and although the city still exists, it has never reached the proportion it was on that historical day. With the presence of the American Wood Rim Co. and its sister company, the Lobdell Emerey Manufacturing Co., Onaway experienced tremendous growth in its early year. The big industry, along with the profitable timber business made Onaway the biggest little town in northern Michigan. According to one report, Onaway had two newspapers, three lawyers, four doctors, three large hotels, 17 saloons, nine churches, two bakeries, a fairgrounds, racetrack and an opera house in the pre-fire days. The figure varies, but Onaway’s population was approximately 4,000 and the two huge industries employed anywhere from 1200 to 1500 persons. The Lobdell Emery Manufacturing co. was involved in lumbering, sawmill operations and the making of such products as dowels, broom handles, and coat hanger stock. The American Wood Rim Co., was the world’s largest and finest producer of automobile steering wheels and bicycle rims. For a number of years the company made all the steering wheels with either malleable iron or aluminum spiders. The alumi- num spiders were all molded and finished in the plant while the malleable iron castings were purchased from outside sour- ces. During its last few years in Onaway, the American Wood Rim Co. -

Exhibition Brochure

Detroit Photographs I Detroit Photographs 1 RUSS MARSHALL Detroit Photographs, 1958–2008 Nancy Barr Like a few bars of jazz improvisation, Russ James Pearson Duffy Curator of Photography Marshall’s photographs of city nights, over- time shifts, and solitary moments in a crowd resonate in melodic shades of black and white. In his first museum solo exhibition, we experience six decades of the Motor City through his eyes. Drawn from his archive of 50,000 plus negatives, the photographs in the exhibition celebrate his art and represent just a sample of the 250 works by Marshall acquired by the Detroit Institute of Arts since 2012. Russ Born in 1940 in South Fork, Pennsylvania, Marshall settled in Detroit Detroit Naval aviation still camera photographer. He returned to Detroit Marshall with his family in 1943 and began to pursue photography as a Photographs after military service and continued to photograph throughout the hobby in the late 1950s. Some of his earliest photographs give a city. Ambassador Bridge and Zug Island, 1968, hints at his devel- 2 rare glimpse into public life throughout the city in the post-World 3 oping aesthetic approach. In a long shot looking toward southwest War II years. In Construction Watchers, Detroit, Michigan, 1960, he Detroit, Marshall considers the city’s skyline as an integral part photographed pedestrians as they peer over a barricade to look of the post-industrial urban landscape, a subject he would revisit north on Woodward Avenue, one of Detroit’s main thoroughfares. In throughout his career. The view shows factory smokestacks that other views, Marshall captured silhouetted figures, their shadows, stripe the horizon, and the Ambassador Bridge stretches out over the atmosphere, and resulting patterns of light and dark. -

1St Responder Newspaper

Title Subtitle Frequency Dates Became Less than 5 Issues? 1st Responder Newspaper New Jersey Edition Oct 2004 x 1st Responder Newspaper Ohio/Pennsylvania Edition May 1999 x 4 Wheel & Off-Road Dec 1979 - Apr 1995 x 9N-2N-8N Newsletter Ford Tractors Jan 1988 - Oct 1997 A.A.H.C. Newsletter April 1990 – July 1993 AAA World 6x/yr May/June 1981 – Jan/Feb 1995 AACA Judges Newsletter 3x/yr Dec 1966 - Jan 1989 AAM News Automobile Association of Malaysia Monthly Dec. 1967 – December 1984 DRIVE Abarth Register, USA The Stinger Quarterly Summer 1978 – July 2004 Abbey Newsletter Bookbinding & Conservation Feb 1984 - Dec 1984 Accelerator Auburn-Cord-Duesenberg Museum Accelerator McLaughlin Buick Club of Canada Bimonthly Jan 1972- Present Access Research at the Univ. of Calif. Transportation Center Fall 1993 - Present Accessory & Garage Journal Incomplete 1912-1920 Action '88 Pub. For Lincoln-Mercury Sales Professionals Jul 1988 x Action Era Vehicle Bimonthly Sep/Oct 1967 – Apr/Jun 2001 Action Track Pontiac Aug 1987 - Apr 1991 x Acura Quarterly July 1987 - Apr 1988 x AD&D Automotive Design & Development Monthly Mar 1978-Jun 1978 x ADAC (German) Jul 1986 x Advertising Requirements Oct 1957 x AERO America's Aviation Weekly Apr 1911 x AFAS Quarterly Automotive Fine Arts Society Quarterly Winter 1989 – 2004 AFV Alternative Fuel Vehicle Report (Ford Motor Co.) Jan 1991 - Aug 1991 x Ahrens-Fox Bulletin Air Cooled News H.H. Franklin Club 3x/yr Mar 1968 – Present Airflow Newsletter Airflow Club of America Monthly Oct. 1963 – Sept 1993 Alarm Room News Sep 1983 -

Marque Club Web Address National Clubs

Marque Club Web Address National Clubs ACD Auburn Cord Duesenberg Club www.acdclub.org AACA Antique Automobile Club of America www.aaca.org BMW BMW Car Club of America www.bmwcca.org CCCA Classic Car Club of America [email protected] CCA Corvette Club of America, www.vette-club.org FCA Ferrari Club of America www.ferrariclubofamerica.org GOOD-GUYS Good-Guys Hotrod Association www.good-guys.com HCCA Horseless Carriage Club of America www.hcca.org HHRA National Hotrod Association www.nhra.com MBCA Mercedes-Benz Club of America www.mbca.org MCA Mustang Club of America www.mustang.org NMCA National Muscle Car Association www.nmcadigital.com NSRA National Street Rod Association www.nsra-usa.com PCA Porsche Club of America www.pca.org RROC Rolls-Royce Owners Club www.rroc.org SCCA Sportscar Club of America www.scca.com SVRA Sportscar Vintage Racing Association www.svra.org VMCCA Veteran Motor Car Club Of America www.vmcca.org VCCA Vintage Car Club of American www.soilvcca.com VMC Vintage Motorsports Council www.the-vmc.com VSCCA Vintage Sports Car Club of America www.vscca.org VCA Volkswagen Club of America www.vwclub.org SINGLE MARQUE: AUTOS AC AC Owners Club http://acowners.club ALFA ROMEO Alfa Romeo Owners Club http://www.aroc-usa.org ALLARD Allard Owners Club www.allardownersclub.org ALVIS North American Alvis Owners Club http://www.alvisoc.org AMC American Motors Owners Association www.amonational.com AMERICAN AUSTIN/BANTAM American Austin/Bantam Club www.austinbantamclub.com AMPHICAR International Amphicar Owners Club www.amphicar.com AUBURN/CORD/DUESENBERG Auburn Cord Duesenberg Club http://www.acdclub.org AUSTIN-HEALEY Austin-Healey Club of America http://www.healeyclub.org AVANTI Avanti Owners Association International, www.aoai.org BRICKLIN Bricklin International Owners Club www.bricklin.org BUGATTI American Bugatti Club, http://www.americanbugatticlub.org BUICK Buick Club of America www.buickclub.org CADILLAC Cadillac and LaSalle Club, www.cadillaclasalleclub.org CHECKER Checker Car Club of America www.checkerworld.org CHEVROLET American Camaro Assoc. -

General Motors

Draft, October 27, 2004 WHEN DOES A CONTRACTUAL ADJUSTMENT INVOLVE A HOLDUP?: THE DYNAMICS OF FISHER-BODY- GENERAL MOTORS Benjamin Klein* I. Introduction Fisher Body-General Motors has become a classic example in economics. Since the brief discussion of the case 35 years ago,1 it has been cited more than one thousand times,2 primarily to illustrate the now generally accepted proposition that vertical integration is more likely when transactors make relationship-specific investments.3 The theoretical and empirical confirmation of this proposition is described by Michael Whinston as “one of the great success stories in industrial organization over the last 25 years.”4 The popularity of the Fisher Body-General Motors case may be difficult to understand since it is merely one of many documented examples of the relationship between vertical integration and specific investments.5 However, the Fisher Body-General Motors case uniquely focuses on the dynamics of this * Professor Emeritus, UCLA. I wish to thank Armen Alchian, Paul Joskow, Victor Goldberg, Tom Hubbard, Scott Masten, Harold Mulherin, Mike Smith, and especially Andres Lerner and Kevin Murphy for comments. Bryan Buskas, Joe Tanimura, Tiffany Truong and Joshua Wright provided research assistance. Earlier versions of the paper were presented at Claremont McKenna College and the ISNIE session of the 2004 ASSA meetings in San Diego. 1 Klein, Crawford and Alchian (1978) at 308-310. 2 There are 1,089 cites to Klein, Crawford and Alchian in the Social Sciences Citation Index, October 19, 2004. 3 [Oliver Williamson cites.] 4 Whinston (2001) at 185. 1 relationship. General Motors was not always vertically integrated with Fisher Body. -

State Has Projects List for Obama

20081215-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CD_-- 12/12/2008 7:08 PM Page 1 ® WWW.CRAINSDETROIT.COM VOL. 24, NO. 50 DECEMBER 15 – 21, 2008 $2 A COPY; $59 A YEAR ©Entire contents copyright 2008 by Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved THIS JUST IN State has projects list for Obama Great Lakes Recycling to add 2 new facilities gan of those kinds of projects, because of Roseville-based Great The tally: roads, bridges, schools, energy TRANSIT PLAN the budgetary con- Lakes Recycling plans a BY AMY LANE The plans are being drawn up in Congress. Backers say $10.5B in straints that we’ve grand opening Jan. 13 on a investment will bring CAPITOL CORRESPONDENT There are discussions indicating that as ear- had over the course $12 million, 50,000-square- $42B in development. ly as mid-January, Congress could pass at least of time, and also foot plant in Wayne Coun- LANSING — Being needy might be good. part of a spending plan for Obama to sign on Page 16. some of the bud- ty’s Huron Township. Also, That’s the hope of Michigan business and Jan. 20, his inauguration. getary decisions the company is looking to government officials, as they eye how a state Across Michigan, projects are being tallied made in Washington,” said Arnold Weinfeld, purchase another building with high unemployment, a struggling econo- that include roads and bridges, water and sew- director of public policy and federal affairs for in metro Detroit to expand my and challenged road systems can tap into er, school and university upgrades, and gov- the Michigan Municipal League. -

Mitrray P Ex Ad

1 TOWGBT GLOBE '.' TONIGHT 1 !lì t--j Dr Tloss office will clnsed be (lawn is depicted from October 3 to October 27. A eiil's great atlventure between dawn and Advrrtisement. 84-O- ct 27 amaziiiglv in BOiìEUT '.. LEO.VARD'S presentation of Mrs. B. E. Doyle has returned from Boston where she has been taking special tiaining under Mrs. MAE Lilla Viles Wyman in modem training of children, also in ali the Fiotti Investors Guaio, Ausrust, 1!)22 modem lanees. Arsene Gicnier loft Thursday for New York city where he has MI TRRAY (Continued Doni Caledonian of Sat., Oct. 14) the outstanding stock of the various divisionai com- takon a position with an automo- The two Durant cars have a bijf field aboard as well panies into the parent corporation' shares between bile concern. IVs ioasted. This as at home, inasmuch as foreijrn as well as domestic August 1, 1924, and August 1, 1920, on bases of $:!() to Miss Khea C. Gilson, a teachor extra process $40 i ; ha re for Durant Motors, Inc., stock. one users aie appreciative of automobiles of merit at . righi in the schools of Springfield, this to-da- y y q detightful priees. Althou;h there aie in the world approx-ìmatcl- For example, the holders of the stock of the Durant state was in St. Johnsbury last gives 12,1)00,000 ?asoline-piopelle- d vehicles, mpie than Motor Company of Indiana, Inc., of whose .'100,000 shares, week to attend the teachers' con- quality that can 10,000,000 of these vehicles are in the United States and having a par value of $10, 240,000 shares have been au- vention and remained until Sunday not be duplicateci tlie remaininp 2,000,000 scatterei! ali over the world.