Architecture and Visual Narrative †

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“HERE/AFTER: Structures in Time” Authors: Paul Clemence & Robert

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Book : “HERE/AFTER: Structures in Time” Authors: Paul Clemence & Robert Landon Featuring Projects by Zaha Hadid, Jean Nouvel, Frank Gehry, Oscar Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe, and Many Others, All Photographed As Never Before. A Groundbreaking New book of Architectural Photographs and Original Essays Takes Readers on a Fascinating Journey Through Time In a visually striking new book Here/After: Structures in Time, award-winning photographer Paul Clemence and author Robert Landon take the reader on a remarkable tour of the hidden fourth dimension of architecture: Time. "Paul Clemence’s photography and Robert Landon’s essays remind us of the essential relationship between architecture, photography and time," writes celebrated architect, critic and former MoMA curator Terence Riley in the book's introduction. The 38 photographs in this book grow out of Clemence's restless search for new architectural encounters, which have taken him from Rio de Janeiro to New York, from Barcelona to Cologne. In the process he has created highly original images of some of the world's most celebrated buildings, from Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum to Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao. Other architects featured in the book include Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Oscar Niemeyer, Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, I.M. Pei, Studio Glavovic, Zaha Hadid and Jean Nouvel. However, Clemence's camera also discovers hidden beauty in unexpected places—an anonymous back alley, a construction site, even a graveyard. The buildings themselves may be still, but his images are dynamic and alive— dancing in time. Inspired by Clemence's photos, Landon's highly personal and poetic essays take the reader on a similar journey. -

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower by KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO

Foster + Partners Bests Zaha Hadid and OMA in Competition to Build Park Avenue Office Tower BY KELLY CHAN | APRIL 3, 2012 | BLOUIN ART INFO We were just getting used to the idea of seeing a sensuous Zaha Hadid building on the corporate-modernist boulevard that is Manhattan’s Park Avenue, but looks like we’ll have to keep dreaming. An invited competition to design a new Park Avenue office building for L&L Holdings and Lemen Brothers Holdings pitted starchitect against starchitect (with a shortlist including Hadid and Rem Koolhaas’s firm OMA). In the end, Lord Norman Foster came out victorious. “Our aim is to create an exceptional building, both of its time and timeless, as well as being respectful of this context,” said Norman Foster in a statement, according to The Architects’ Newspaper. Foster described the building as “for the city and for the people that will work in it, setting a new standard for office design and providing an enduring landmark that befits its world-famous location.” The winning design (pictured left) is a three-tiered, 625,000-square-foot tower. With sky-high landscaped terraces, flexible floor plates, a sheltered street-level plaza, and LEED certification, the building does seem to reiterate some of the same principles seen in the Lever House and Seagram Building, Park Avenue’s current office tower icons, but with markedly updated standards. Only time will tell if Foster’s building can achieve the same timelessness as its mid-century predecessors, a feat that challenged a slew of architects as Park Avenue cultivated its corporate identity in the 1950s and 60s. -

Venice & the Common Ground

COVER Magazine No 02 Venice & the Common Ground Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 01 of 02 EDITORIAL 04 STATEMENTS 25 - 29 EDITORIAL Re: COMMON GROUND Reflections and reactions on the main exhibition By Pedro Gadanho, Steven Holl, Andres Lepik, Beatrice Galilee a.o. VIDEO INTERVIew 06 REPORT 30 - 31 WHAT IS »COMMON GROUND«? THE GOLDEN LIONS David Chipperfield on his curatorial concept Who won what and why Text: Florian Heilmeyer Text: Jessica Bridger PHOTO ESSAY 07 - 21 INTERVIew 32 - 39 EXCAVATING THE COMMON GROUND STIMULATORS AND MODERATORS Our highlights from the two main exhibitions Jury member Kristin Feireiss about this year’s awards Interview: Florian Heilmeyer ESSAY 22 - 24 REVIEW 40 - 41 ARCHITECTURE OBSERVES ITSELF GUERILLA URBANISM David Chipperfield’s Biennale misses social and From ad-hoc to DIY in the US Pavilion political topics – and voices from outside Europe Text: Jessica Bridger Text: Florian Heilmeyer Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 02 TABLE OF CONTENTS Part 02 of 02 ReVIEW 42 REVIEW 51 REDUCE REUSE RECYCLE AND NOW THE ENSEMBLE!!! Germany’s Pavilion dwells in re-uses the existing On Melancholy in the Swiss Pavilion Text: Rob Wilson Text: Rob Wilson ESSAY 43 - 46 ReVIEW 52 - 54 OLD BUILDINGS, New LIFE THE WAY OF ENTHUSIASTS On the theme of re-use and renovation across the An exhibition that’s worth the boat ride biennale Text: Elvia Wilk Text: Rob Wilson ReVIEW 47 ESSAY 55 - 60 CULTURE UNDER CONSTRUCTION DARK SIDE CLUB 2012 Mexico’s church pavilion The Dark Side of Debate Text: Rob Wilson Text: Norman Kietzman ESSAY 48 - 50 NEXT 61 ARCHITECTURE, WITH LOVE MANUELLE GAUTRAND Greece and Spain address economic turmoil Text: Jessica Bridger Magazine No 02 | Venice & the Common Ground | Page 03 EDITORIAL Inside uncube No.2 you’ll find our selections from the 13th Architecture Biennale in Venice. -

Introduction Association (AA) School Where She Was Awarded the Diploma Prize in 1977

Studio London Zaha Hadid, founder of Zaha Hadid Architects, was awarded the Pritzker 10 Bowling Green Lane Architecture Prize (considered to be the Nobel Prize of architecture) in 2004 and London EC1R 0BQ is internationally known for her built, theoretical and academic work. Each of T +44 20 7253 5147 her dynamic and pioneering projects builds on over thirty years of exploration F +44 20 7251 8322 and research in the interrelated fields of urbanism, architecture and design. [email protected] www.zaha-hadid.com Born in Baghdad, Iraq in 1950, Hadid studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut before moving to London in 1972 to attend the Architectural Introduction Association (AA) School where she was awarded the Diploma Prize in 1977. She founded Zaha Hadid Architects in 1979 and completed her first building, the Vitra Fire Station, Germany in 1993. Hadid taught at the AA School until 1987 and has since held numerous chairs and guest professorships at universities around the world. She is currently a professor at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and visiting professor of Architectural Design at Yale University. Working with senior office partner, Patrik Schumacher, Hadid’s interest lies in the rigorous interface between architecture, landscape, and geology as her practice integrates natural topography and human-made systems, leading to innovation with new technologies. The MAXXI: National Museum of 21st Century Arts in Rome, Italy and the London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Olympic Games are excellent manifestos of Hadid’s quest for complex, fluid space. Previous seminal buildings such as the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati and the Guangzhou Opera House in China have also been hailed as architecture that transforms our ideas of the future with new spatial concepts and dynamic, visionary forms. -

Rug01-002224449 2015 0001 Ac

1 Textiel en/in architectuur Louis De Mey Promotoren: prof. dr. Bart Verschaffel, dr. ir.-arch. Maarten Van Den Driessche Begeleiders: Stefaan Vervoort, Maarten Liefooghe, Pieter-Jan Cierkens, dr. ir.-arch. Christophe Van Gerrewey Masterproef ingediend tot het behalen van de academische graad van Master of Science in de ingenieurswetenschappen: architectuur Vakgroep Architectuur en Stedenbouw Voorzitter: prof. dr. ir. Arnold Janssens Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen en Architectuur Academiejaar 2014-2015 DEEL 1- INLEIDING: Textiel in verhouding tot architectuur INLEIDING: TEXTIEL EN ARCHITECTUUR 3 MARGINALISERING VAN TEXTIEL BINNEN DE ARCHITECTUURDISCIPLINE 3 RELEVANTIE VAN TEXTIEL VOOR ARCHITECTUUR 3 THEORETISCHE OMKADERING 5 VISUELE CONTEXTUALISERING 5 Architectuur 5 Textielontwerp en Design 5 Beeldende kunsten 5 TEXTUELE CONTEXTUALISERING 6 Textiel als centraal onderzoeksthema 7 De ‘Bekleidung’-Metafoor 7 Het taboe 8 Teksten als onderdeel van een discours/oeuvre 8 WAT MET KLEDING 9 DE METAFOOR VAN DE TWEEDE HUID 9 KLEDIJ ALS TIENDE TEXTIELTYPOLOGIE 9 MODE EN TRENDS 9 2 INLEIDING: T EX T IEL EN ARCHITECTUUR Het gebruik van textiel in architectuur komt zeer vanzelfsprekend over, en is alomtegenwoordig. Toch vormt het bespreken van textieltoepassingen binnen het kader van architectuur een niet zo geëxploreerd onderwerp. De textielelementen waarover deze masterproef zal spreken, zijn eeuwenoud en beladen met betekenis. Er bestaan echter er nog geen studies die dit onderwerp concreet adresseren. Deze masterproef zal de rijkdom van deze textielelementen trachten duidelijk te maken, alsook wat ze kunnen betekenen voor de architectuur. Marginalisering van textiel binnen de architectuurdiscipline Om te beginnen is textiel een materiaal dat dermate alledaags is, dat we er amper aandacht aan besteden. We herkennen en erkennen de pracht en praal van luxueuze stoffen als fijne zijde en brokaat wel, maar de kwaliteiten die een simpel weefsel of breisel bezit zien we al te vaak niet. -

Half Floor Residences - Zone 2 - Levels 26-33

NORTH 2802 MASTER CLOSET BEDROOM 4 KITCHEN 15’ 6’’ X 11’ 0’’ 32’ 0’’ X 21’ 8’’ TERRACE TERRACE MASTER BATHROOM HALF FLOOR RESIDENCES - ZONE 2 - LEVELS 26-33 OPTIONAL WALL MIDNIGHT WET BAR 4 BEDROOM - 5.5 BATHROOM MASTER BEDROOM 29’ 0’’ X 14’ 0’’ 01 LINE 02 LINE WET BAR INTERIORS: 4,599 SQFT 427 M2 TERRACE: 781 SQFT 73 M2 WEST EAST TOTAL AREA: 5,380 SQFT 500 M2 GREAT ROOM BEDROOM 2 31’ 0’’ X 47’ 8’’ 18’ 11’’ X 12’ 11’’ STAFF / LAUNDRY NORTH TO DESIGN DISTRICT WYNWOOD FOYER BEDROOM 3 I-195 TERRACE HALF FLOOR HALF FLOOR 3’ 10’’ X 27’ 0’’ 22’ 0’’ X 13’ 0’’ RESIDENCES RESIDENCES ZONE 2 ZONE 2 11TH STREET O2 LINE O2 LINE MUSEUM PARK 0202 LINE 01 10TH STREET WEST EAST TO MIAMI TO MIAMI INTERNATIONAL I-95 BEACH AIRPORT 9TH STREET BISCAYNE BAY NE 2 AVENUE AMERICAN BISCAYNE BOULEVARD BISCAYNE AIRLINES ARENA MIAMI HEAT 7TH STREET TERRACE 3’ 10’’ X 27’ 0’’ BEDROOM 3 SOUTH TO DOWNTOWN MIAMI 22’ 0’’ X 12’ 0’’ KEY BISCAYNE FOYER STAFF / LAUNDRY BEDROOM 2 TOWER FEATURES AMENITIES 14’ 9’’ X 12’ 11’’ GREAT ROOM – - ARCHITECTURE AND AMENITY SPACES DESIGNED BY ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS – - OUTDOOR POOL & RECREATIONAL TERRACE 31’ 0’’ X 47’ 8’’ – - LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE BY ENZO ENEA – - FITNESS CENTER – - MUSEUM-QUALITY INTERIOR AND EXTERIOR ILLUMINATION – - SPA – - AMENITY SPACE SCENTING CRAFTED BY 12.29 OLFACTORY CONSULTANTS – - INDOOR AQUATIC CENTER WEST EAST – - FUNCTIONALLY INTEGRATED SECURITY AND TECHNOLOGY PROGRAM – - SKY LOUNGE – - PRIVATE ROOFTOP HELIPAD WET BAR RESIDENTIAL FEATURES – - SECURE ON-SITE PARKING – - ESTATE-SIZE HALF-FLOOR, FULL-FLOOR, AND -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

La Difusió D

ADVERTIMENT . La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX ( www.tesisenxarxa.net ) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA . La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR ( www.tesisenred.net ) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos. En la utilización o cita de partes de la tesis es obligado indicar el nombre de la persona autora. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

Architecture: the Museum As Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12

Architecture: The Museum as Muse Museum Education Program for Grades 6-12 Program Outline & Volunteer Resource Package Single Visit Program Option : 2 HOURS Contents of Resource Package Contents Page Program Development & Description 1 Learning Objectives for Students & Preparation Guidelines 2 One Page Program Outline 3 Powerpoint Presentation Overview 4 - 24 Glossary – Architectural Terms 24 - 27 Multimedia Resource Lists (Potential Research Activities) 27 - 31 Field Journal Sample 32 - 34 Glossary – Descriptive Words Program Development This programme was conceived in conjunction with the MOA Renewal project which expanded the Museum galleries, storages and research areas. The excitement that developed during this process of planning for these expanded spaces created a renewed enthusiasm for the architecture of Arthur Erickson and the landscape architecture of Cornelia Oberlander. Over three years the programme was developed with the assistance of teacher specialists, Jane Kinegal, Cambie Secondary School and Russ Timothy Evans, Tupper Secondary School. This programme was developed under the direction of Jill Baird, Curator of Education & Public Programmes, with Danielle Mackenzie, Public Programs & Education Intern 2008/09, Jennifer Robinson, Public Programs & Education Intern 2009/10, Vivienne Tutlewski, Public Programs & Education Intern 2010/2011, Katherine Power, Public Programs & Education Workstudy 2010/11, and Maureen Richardson, Education Volunteer Associate, who were all were key contributors to the research, development and implementation of the programme. Program Description Architecture: The Museum as Muse, Grades 6 - 12 MOA is internationally recognized for its collection of world arts and culture, but it is also famous for its unique architectural setting. This program includes a hands-on phenomenological (sensory) activity, an interior and exterior exploration of the museum, a stunning visual presentation on international museum architecture, and a 30 minute drawing activity where students can begin to design their own museum. -

Les Journées De L'architecture Die Architekturtage

Architectures Architektur en lumière im Licht les journées de l’architecture die Architekturtage 25.09 ,24.10 2015 Il y a mille et une façons de « lire » l’architecture MaNNHEIM et trois façons de consulter ce programme… À vous de choisir le sommaire qui vous convient : par villes (ci-dessous), par manifestations (pages 2 à 8) ou par dates (en fin de programme). Es gibt unendlich viele Möglichkeiten, Architektur zu „lesen“, BaD SCHÖNBORN bei diesem Programm genügen drei: entweder nach Städten (siehe unten), nach Veranstaltungsarten (Seiten 2 bis 8) oder nach Datum (am Ende des Programmheftes). Wählen Sie die Form aus, die Ihnen am besten gefällt! WISSEMBOURG ●F Pour un public francophone | KaRLSRUHE Für französischsprachiges Publikum PREUSCHDORF ●D Pour un public germanophone | HAGUENAU Für deutschsprachiges Publikum NANCY % DRUSENHEIM BaDEN-BaDEN BRUMATH SINGRIST BÜHL SCHILTIGHEIM Sans frontière 26 Mannheim 106 STRASBOURG OSTWalD Toute l’Alsace 38 Mulhouse 108 IllKIRCH-GRAFFENSTADEN OBERKIRCH OFFENBURG Altkirch 42 Nancy 128 OBERNAI Baden-Baden 44 Oberkirch 130 Bad Schönborn 46 Obernai 132 SÉLESTAT Basel 48 Offenburg 134 Brumath 52 Ostwald 138 ColMAR Bühl 54 Preuschdorf 140 Colmar 58 Saint-Louis 142 FREIBURG IM BREISGAU Drusenheim 66 Schiltigheim 144 GUEBWILLER Freiburg 68 Sélestat 148 Guebwiller 82 Singrist 150 MULHOUSE Haguenau 84 Strasbourg 152 ALTKIRCH SAINT-LOUIS Illkirch-Graffenstaden 86 Wissembourg 208 BaSEL Karlsruhe 92 2 MANIFESTATIONS | VERANSTALTUNGEN MANIFESTATIONS | VERANSTALTUNGEN 3 Ouverture | Eröffnung Lumières sur le parc -

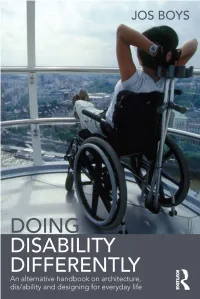

Doing Disability Differently

Doing Disability Differently This ground-breaking book aims to take a new and innovative view on how disability and architecture might be connected. Rather than putting disability at the end of the design process, centred mainly on compliance, it sees disability – and ability – as creative starting points. It asks the intriguing question: can working from dis/ability actually generate an alternative kind of architectural avant-garde? To do this, Doing Disability Differently: • explores how thinking about dis/ability opens up to critical and creative investigation our everyday social attitudes and practices about people, objects and space; • argues that design can help resist and transform underlying and unnoticed inequalities; • introduces architects to the emerging and important field of disability stud- ies and considers what different kinds of design thinking and doing this can enable; • asks how designing for everyday life – in all its diversity – can be better embedded within contemporary architecture as a discipline; • offers examples of what doing disability differently can mean for architec- tural theory, education and professional practice; • aims to embed into architectural practice attitudes and approaches that creatively and constructively refuse to perpetuate body ‘norms’ or the resulting inequalities in access to, and support from, built space. Ultimately, this book suggests that re-addressing architecture and disability involves nothing less than re-thinking how to design for the everyday occupa- tion of space more generally. Jos Boys is a Teaching Fellow in the Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sci- ences at the University of Northumbria. She brings together a background in architecture with a research interest in the relationships between space and its occupation, and an involvement in many disability related projects.