Humanrightsabuseiniran 2010.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly

United Nations A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 General Assembly Distr.: General 25 February 2010 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Manfred Nowak Addendum Summary of information, including individual cases, transmitted to Governments and replies received* * The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only as it greatly exceeds the page limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11514 A/HRC/13/39/Add.1 Contents Paragraphs Page List of abbreviations......................................................................................................................... 5 I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–5 6 II. Summary of allegations transmitted and replies received....................................... 1–305 7 Algeria ............................................................................................................ 1 7 Angola ............................................................................................................ 2 7 Argentina ........................................................................................................ 3 8 Australia......................................................................................................... -

Chapter Iii Iranian Government Policies Toward Kurdish Minority

CHAPTER III IRANIAN GOVERNMENT POLICIES TOWARD KURDISH MINORITY In this chapter, the writer will describe the condition of Kurdish minority ethnic in Iran, a situation that describes the treatments of Persian regime toward Kurds. The elaboration of Iranian government policies itself will be categorized on the segment of issues. Policies that produced by a dynasty of Persia, Pahlavi Dynasty that was ordered by two Shah1 puts several limits on the social and cultural activities of the Kurds in Iran to current time.2 Categorization is used as tool to ease understanding of short history of Iranian Kurds that reflects and creates Kurds condition today. Life of Kurdish people in Iran today has been known for a long time. The origin of Kurds that believed to have connection to Persians make their relation can be seen as one coin in different side. Nonetheless, Persians nation, time by time, always dominate the land of Iran and Kurds nation who live in Persians authority, they only stay on small area who acted as civilians, not the rulers. Fact that Kurds often being ruled than ruling and over domination of Persians rulers toward other nations in their authority inevitably gave some side effects to Kurds nations, especially Iranian Kurds. Feeling of marginalized to the repressive actions and policies from Tehran authority later made Iranian Kurds was treated as second-class society. Here, there are brief examples of Iranian major policies toward Kurds nation in some issues. 1 Shah literally means King in Persian Empire, Dictionary on web http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/shah, consulted on 20 April 2015 2 Info on Kurds, http://kurdishrights.org/info-on-kurds/, consulted on 20 April 2015. -

Decentralization and Democracy in Iran

DECENTRALIZATION AND DEMOCRACY IN IRAN SAEID NOURI NESHAT THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENTMalaya OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHYof FACULTY OF ECONOMICS AND ADMINISTRATION UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA UniversityKUALA LUMPUR 2017 i Abstract It was only twenty years after the 1979 Revolution that local Islamic councils were legalized and launched everywhere in Iran as part of reforms to strengthen decentralization and enhance people’s participation in policy planning. However, although these councils comprise elected members, they have not been fully institutionalized within the local government system and within Iran’s hierarchy of power. Local councils, therefore, have not led to the greater empowerment of people. This study assesses the decentralization process within the power structure after the Iranian Revolution. The research aims to provide insights into these key questions: how was the structure of the post-revolution decentralization system different from that of the previous regime? Why has the policy of decentralizationMalaya not led to the sort of devolution that would enable people to participateof in decision-making? What are the political obstacles to the empowerment of the people, a professed goal of the post- revolution government? A qualitative research method involving a multiple case study approach is used here. Urban and rural communities were selected for assessment through purposive sampling. Easton’s theory of political system was applied as it provides an effective conceptual framework to examine and explain the data. TheUniversity results indicate that the post-revolution system is one that can be classified as a filtered democracy. In this type of political system, inputs from society have to pass through filters created by power elites. -

General Assembly A/HRC/13/22/Add.1 24 February 2010

UNITED NATIONS A Distr. GENERAL General Assembly A/HRC/13/22/Add.1 24 February 2010 ENGLISH/FRENCH/SPANISH ONLY HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF ALL HUMAN RIGHTS, CIVIL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya Addendum Summary of cases transmitted to Governments and replies received∗ ∗ The present document is being circulated in the languages of submission only, as it greatly exceeds the word limitations currently imposed by the relevant General Assembly resolutions. GE.10-11297 A/HRC/13/22/Add.1 Page 2 Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................5 Algeria .......................................................................................................................................5 Argentina ...................................................................................................................................8 Azerbaijan................................................................................................................................16 Bahrain.....................................................................................................................................18 Belarus .....................................................................................................................................20 -

Macron Confounding France

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 16 Pages Price 20,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 39th year No.13271 Thursday DECEMBER 6, 2018 Azar 15, 1397 Rabi’ Al awwal 28, 1440 Prayer can lift up 2231 resolution Iranian trio Blind artist to hold society’s virtue doesn’t limit missile appointed for workshop to erase doubts 2 program 2 2019 AFC Asian Cup 15 over her ability to paint 16 Anti-Iran consensus Macron confounding France fails at UN POLITICS TEHRAN – Attempts France seized the moment to wring deskto bring the United Na- an agreement against Iran’s missile As France faces worst riots, Paris sends rockets to terrorists tions Security Council into a consensus tests out of the session. against Iran’s missile tests failed to achieve The two European countries’ attempt to do chemical attacks in Syria the desired conclusion sought by the U.S., followed U.S. claim that Iran’s missile test France and Britain. was a violation of UN Security Council On Tuesday, the UN Security Resolution 2231 which endorsed the nu- See page 13 Council held a closed session whose clear agreement, officially known as the primary focus was the use of chem- JCPOA (the Joint Comprehensive Plan ical weapons in Syria. Britain and of Action). 2 Iran to carry out cloud seeding project by drones in weeks SOCIETY TEHRAN — A cloud Cloud seeding, a form of weather deskseeding project will modification, is a method to change the be carried out within the next few weeks amount or even type of precipitation. -

PDF Document

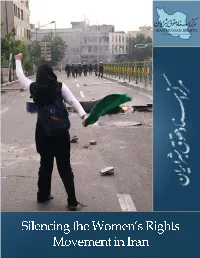

Iran Human Rights Documentation Center The Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (IHRDC) believes that the development of an accountability movement and a culture of human rights in Iran are crucial to the long-term peace and security of the country and the Middle East region. As numerous examples have illustrated, the removal of an authoritarian regime does not necessarily lead to an improved human rights situation if institutions and civil society are weak, or if a culture of human rights and democratic governance has not been cultivated. By providing Iranians with comprehensive human rights reports, data about past and present human rights violations and information about international human rights standards, particularly the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the IHRDC programs will strengthen Iranians’ ability to demand accountability, reform public institutions, and promote transparency and respect for human rights. Encouraging a culture of human rights within Iranian society as a whole will allow political and legal reforms to have real and lasting weight. The IHRDC seeks to: . Establish a comprehensive and objective historical record of the human rights situation in Iran since the 1979 revolution, and on the basis of this record, establish responsibility for patterns of human rights abuses; . Make such record available in an archive that is accessible to the public for research and educational purposes; . Promote accountability, respect for human rights and the rule of law in Iran; and . Encourage an informed dialogue on the human rights situation in Iran among scholars and the general public in Iran and abroad. Iran Human Rights Documentation Center 129 Church Street New Haven, Connecticut 06510, USA Tel: +1-(203)-772-2218 Fax: +1-(203)-772-1782 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.iranhrdc.org Photograph: The front cover photo shows a female protestor during the post-election demonstrations facing approaching security forces. -

Architectural Criticism of Nasir Al-Molk Mosque in Shiraz Based on Religious Texts*

Bagh-e Nazar, 16(78), 57-74 / Dec. 2019 DOI: 10.22034/bagh.2019.104311.3283 Persian translation of this paper entitled: نقد معماری مسجد نصیرالملک شیراز براساس نصوص دینی is also published in this issue of journal. Architectural Criticism of Nasir Al-Molk Mosque in Shiraz Based on Religious Texts* Mohsen Akbarzadeh1, Marzieh Piravi Vanak**2, Farhang Mozaffar3 1. PhD. Candidate in Islamic Architecture, Architecture Department, Art University of Isfahan, Iran. 2. Art Research Department, Art University of Isfahan, Iran. 3. Architecture Department, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran. Received: 11/12/2017 ; revised: 17/11/2018 ; accepted: 02/12/2018 ; available online: 22/11/2019 Abstract Problem statement: Nasir al-Molk mosque, which is described in architectural writing resources as a distinct mosque, has become a tourism center in Shiraz for many years and seems to have lost its devotional function. This distinction from the mosques with a more historical dating in Shiraz results in the assumption that the architectural features of this mosque are the reason for this distinction. Characteristics that come with the change or emphasis of common patterns in traditional mosques, and field observations and reviewing the documents of related resources include the lack of elongation of the prayer hall perpendicular to the axis of the qibla, the aberration of the perception of the qibla, the maximum decorations in the space of worship and the likeness to non-Muslim patterns. In order to examine these characteristics that cprayer hallenge the historic originality, it is necessary to refer to non-timely religious criteria, which goes beyond this feature, to ensure the devotional function of the mosque in an optimal way. -

Censorship of Poetry in Post-Revolutionary Iran (1979 to 2014), Growing up with Censorship (A Memoir), and the Kindly Interrogator (A Collection of Poetry)

Censorship of Poetry in Post-Revolutionary Iran (1979 to 2014), Growing up with Censorship (A Memoir), and The Kindly Interrogator (A Collection of Poetry) Alireza Hassani This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Newcastle University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics Department of Creative Writing November 2015 Abstract The thesis comprises a dissertation, a linking piece and a collection of poems. The dissertation is an analysis of state-imposed censorship in Iranian poetry from 1979 through 2014. It investigates the state's rationale for censorship, its mechanism and its effects in order to show how censorship has influenced the trends in poetry and the creativity of poets during the period studied. The introduction outlines attitudes towards censorship in three different categories: Firstly, censorship as "good and necessary", then censorship as "fundamentally wrong yet harmless or even beneficial to poetry", and lastly, censorship as a force that is always destructive and damages poetry. Chapter one investigates the relevant laws, theories and cultural policies in order to identify the underlying causes for censorship of poetry. Chapter two looks at the structure and mechanism of the censorship apparatus and examines the role of cultural organizations as well as judicial and security forces in enforcing censorship. Chapter three contemplates and explores the reaction of Iranian poets to censorship and different strategies and techniques they adopt to protest, challenge and circumvent censorship. Chapter four analyses the outcome of the relationship between the censorship apparatus and the poets, providing a clear picture of how censorship defines, shapes and presents the poetry produced and published in Iran. -

Archive of SID

Archive of SID Bagh-e Nazar, 16(78), 57-74 / Dec. 2019 DOI: 10.22034/bagh.2019.104311.3283 Persian translation of this paper entitled: نقد معماری مسجد نصیرالملک شیراز براساس نصوص دینی is also published in this issue of journal. Architectural Criticism of Nasir Al-Molk Mosque in Shiraz Based on Religious Texts* Mohsen Akbarzadeh1, Marzieh Piravi Vanak**2, Farhang Mozaffar3 1. PhD. Candidate in Islamic Architecture, Architecture Department, Art University of Isfahan, Iran. 2. Art Research Department, Art University of Isfahan, Iran. 3. Architecture Department, Iran University of Science and Technology, Tehran, Iran. Received: 11/12/2017 ; revised: 17/11/2018 ; accepted: 02/12/2018 ; available online: 22/11/2019 Abstract Problem statement: Nasir al-Molk mosque, which is described in architectural writing resources as a distinct mosque, has become a tourism center in Shiraz for many years and seems to have lost its devotional function. This distinction from the mosques with a more historical dating in Shiraz results in the assumption that the architectural features of this mosque are the reason for this distinction. Characteristics that come with the change or emphasis of common patterns in traditional mosques, and field observations and reviewing the documents of related resources include the lack of elongation of the prayer hall perpendicular to the axis of the qibla, the aberration of the perception of the qibla, the maximum decorations in the space of worship and the likeness to non-Muslim patterns. In order to examine these characteristics that cprayer hallenge the historic originality, it is necessary to refer to non-timely religious criteria, which goes beyond this feature, to ensure the devotional function of the mosque in an optimal way. -

Iran Human Rights Review

The Iran Human Rights Review, edited by Nazenin Ansari and Tahirih Danesh, is a new Foreign Policy Centre project that seeks to be an important resource for policy makers and activists by combining information and opinion with analysis and recommendations for action. This new edition of the Review focuses on the emergence of access to information as a pivotal element in promoting and protecting the Iranian human IrAN HUmAN rIgHTS rights movement. It contains opinion pieces and detailed articles from a wide range of experts and activists with a focus on promoting a culture of human rights in Iran and the region. Contributors include: Dame Ann Leslie, Nasrin Alavi, Ramin revIew: ACCESS TO Asgard, Shahryar Ahy, Negar Esfandiari, Claudia Mendoza, Saba Farzan, Nazanine Moshiri, Rossi Qajar, Mojtaba Saminejad, Ali Sheikholeslami, Meir Javedanfar, Potkin Azarmehr, Mariam Memarsadeghi. INFORMATION edited by Tahirih Danesh and Nazenin Ansari Preface by Dame Anne Leslie The Foreign Policy Centre Suite 11, Second floor 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL United Kingdom www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2011 All rights reserved Iran Human Rights Review: Access to Information Edited by Tahirih Danesh and Nazenin Ansari Preface by Dame Ann Leslie First published in May 2011 by The Foreign Policy Centre Suite 11, Second Floor 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] ©Foreign Policy Centre 2011 All Rights Reserved Disclaimer: The Iran Human Rights Review is a platform for a diverse range of opinions. The views expressed in this report are those of their authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Foreign Policy Centre. -

Revolution Decoded: Iran's Digital Landscape

Revolution Decoded 1. Tensions and ambiguities 1 in Iranian media law REVOLUTION DECODED: IRAN’S DIGITAL LANDSCAPE This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License Revolution Decoded 1. Tensions and ambiguities 2 in Iranian media law Small Media Editors Bronwen Robertson James Marchant Contributors Kyle Bowen James Marchant Research Assistants Benjamin Graff Marine Strauss Raha Zahedpour Graphic Designers Isabel Beard Richard Kahwagi Arab Media Report Contributors Antonello Sacchetti Valeria Spinelli Revolution Decoded 1. Tensions and ambiguities 3 in Iranian media law 1.TENSIONS AND AMBIGUITIES IN IRANIAN MEDIA LAW by Kyle Bowen Though political Islam sits at the core of Iranian state ideology, its employment as a basis for media governance and regulation has proven to be problematic, and deeply contentious. Revolution Decoded 1. Tensions and ambiguities 1 in Iranian media law Over the course of the last century, through the Pahlavi era and the Islamic Republic, the Iranian media environment has experienced significant levels of state censorship and control. Government censors have meddled in newspapers, radio, publishing, television, and most recently the internet, in order to curtail popular dissent and defend the ideological and political basis of the state. This chapter, which is divided into three sections, addresses the legal and constitutional background against which state censorship in Iran takes place. The first section outlines the ideological background and context of the Iranian constitution, the second discusses the provisions of the constitution pertaining to freedom of expression and discusses relevant legislation, and the third offers two case studies to illustrate how these legal and regulatory frameworks function in practice. -

Esma¨Il Fasih and His War Novel, the Winter of 1983

Persica 24, 51-80. doi: 10.2143/PERS.24.0.3005373 © 2013 by Persica. All rights reserved. ESMA¨IL FASIH AND HIS WAR NOVEL, THE WINTER OF 1983 Saeedeh Shahnapour INTRODUCTION With the inception of the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) came a new chapter in Persian litera- ture from a thematic standpoint. This period has been characterised as “the War Lite- rature” (Adabiyyat-e Jang), “the Literature of Holy Defense” (Adabiyyat-e Defa¨ Moqad- das) and “the Literature of Perseverance and Resistance” (Adabiyyat-e Paydari va Moqavemat), and focuses on the war and the issues stemming from it. Persian authors during this time opted to write long and short stories, as well as novels and memoirs about the event. Many of these writers reveal the profound impact of the conflict in their work, regardless of literary perspectives. Alternatively, others chose to combine more traditional, amorous and domestic melodramas with the aspects of the war to create their war novels.1 Martyrdom (shahadat), captivity (esarat), self-sacrifice (janbazi), bombardments (bom- baran) and “shellshock” syndrome (mouj-gereftegi) rank among the most prominent motifs described in this section of Persian fiction. The main goal of these writers was to inspire people to join the front lines and augment sentiments of military spirit. Esm¨ail Fasih (1935-2009) is considered to be one of the best Persian War novelists of the late twentieth century. With twenty-one published novels, five collections of short stories and eleven translations, he is the most prolific writer of his generation. Fasih wrote both before and after the Islamic Revolution (1978-79).