Japanese Collections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estudo E Desenvolvimento Do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO MESTRADO ACADÊMICO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Juvane Nunes Marciano Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 Juvane Nunes Marciano Aprendizagem da Língua Japonesa Apoiada por Ferramentas Computacionais: Estudo e Desenvolvimento do Jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders Dissertação de Mestrado apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação do Departamento de Informática e Matemática Aplicada da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte como requisito final para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Sistemas e Computação. Linha de pesquisa: Engenharia de Software Orientador Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda PPGSC – PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SISTEMAS E COMPUTAÇÃO DIMAP – DEPARTAMENTO DE INFORMÁTICA E MATEMÁTICA APLICADA CCET – CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS EXATAS E DA TERRA UFRN – UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE Natal-RN Fevereiro de 2014 UFRN / Biblioteca Central Zila Mamede Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte Marciano, Juvane Nunes. Aprendizagem da língua japonesa apoiada por ferramentas computacionais: estudo e desenvolvimento do jogo Karuchā Ships Invaders. / Juvane Nunes Marciano. – Natal, RN, 2014. 140 f.: il. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Leonardo Cunha de Miranda. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Ciências Exatas e da Terra. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sistemas e Computação. 1. Informática na educação – Dissertação. 2. Interação humano- computador - Dissertação. 3. Jogo educacional - Dissertação. 4. Kanas – Dissertação. 5. Hiragana – Dissertação. 6. Roma-ji – Dissertação. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

Identification of Asian Garments in Small Museums

AN ABSTRACTOF THE THESIS OF Alison E. Kondo for the degree ofMaster ofScience in Apparel Interiors, Housing and Merchandising presented on June 7, 2000. Title: Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums. Redacted for privacy Abstract approved: Elaine Pedersen The frequent misidentification ofAsian garments in small museum collections indicated the need for a garment identification system specifically for use in differentiating the various forms ofAsian clothing. The decision tree system proposed in this thesis is intended to provide an instrument to distinguish the clothing styles ofJapan, China, Korea, Tibet, and northern Nepal which are found most frequently in museum clothing collections. The first step ofthe decision tree uses the shape ofthe neckline to distinguish the garment's country oforigin. The second step ofthe decision tree uses the sleeve shape to determine factors such as the gender and marital status ofthe wearer, and the formality level ofthe garment. The decision tree instrument was tested with a sample population of 10 undergraduates representing volunteer docents and 4 graduate students representing curators ofa small museum. The subjects were asked to determine the country oforigin, the original wearer's gender and marital status, and the garment's formality and function, as appropriate. The test was successful in identifying the country oforigin ofall 12 Asian garments and had less successful results for the remaining variables. Copyright by Alison E. Kondo June 7, 2000 All rights Reserved Identification ofAsian Garments in Small Museums by Alison E. Kondo A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master ofScience Presented June 7, 2000 Commencement June 2001 Master of Science thesis ofAlison E. -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

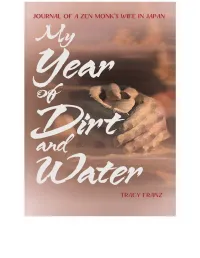

My Year of Dirt and Water

“In a year apart from everyone she loves, Tracy Franz reconciles her feelings of loneliness and displacement into acceptance and trust. Keenly observed and lyrically told, her journal takes us deep into the spirit of Zen, where every place you stand is the monastery.” KAREN MAEZEN MILLER, author of Paradise in Plain Sight: Lessons from a Zen Garden “Crisp, glittering, deep, and probing.” DAI-EN BENNAGE, translator of Zen Seeds “Tracy Franz’s My Year of Dirt and Water is both bold and quietly elegant in form and insight, and spacious enough for many striking paradoxes: the intimacy that arises in the midst of loneliness, finding belonging in exile, discovering real freedom on a journey punctuated by encounters with dark and cruel men, and moving forward into the unknown to finally excavate secrets of the past. It is a long poem, a string of koans and startling encounters, a clear dream of transmissions beyond words. And it is a remarkable love story that moved me to tears.” BONNIE NADZAM, author of Lamb and Lions, co-author of Love in the Anthropocene “A remarkable account of a woman’s sojourn, largely in Japan, while her husband undergoes a year-long training session in a Zen Buddhist monastery. Difficult, disciplined, and interesting as the husband’s training toward becoming a monk may be, it is the author’s tale that has our attention here.” JOHN KEEBLE, author of seven books, including The Shadows of Owls “Franz matches restraint with reflexiveness, crafting a narrative equally filled with the luminous particular and the telling omission. -

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra asijských studií Estetické vnímání krásy ženy v Japonsku Aesthetic perception of woman´s beauty in Japan Bakalářská diplomová práce Autor práce: Pomklová Lucie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Sylva Martinásková - ASJ Olomouc 2013 Kopie zadání diplomové práce Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla veškeré použité prameny a literaturu V Olomouci dne _______________________ Poděkování: Na tomto místě bych chtěla velice poděkovat Mgr. Sylvě Martináskové za konzultace, ochotu, flexibilitu při řešení jakýchkoliv problémů a odborné vedení mé práce. Díky jejím cenným radám a podnětům mohla tato práce vzniknout. Ediční poznámka Ve své práci používám anglický přepis japonských názvů společně se znaky nebo slabičnou abecedou, které budu užívat u ér, období, uvedených japonských termínů a jmen osob. Japonská jména uvádím v japonském pořadí čili první příjmení a za ním teprve následuje jméno osobní, ženská jména jsou uvedena v nepřechýlené podobě. Pro obecně známá místní jména či termíny, u kterých je český přepis již pevně stanoven pravidly českého pravopisu, používám tento do češtiny přejatý tvar. Kurzívu budu používat pro méně známé termíny, názvy ér a období a také pro citace. Používám citační normu ISO 690. Obsah 1 Úvod ................................................................................................................................... 8 2 Protohistorické období .................................................................................................. -

Final-God's Footprint 11-14-2014

! GOD’S FOOTPRINT IN THE MEDIA A Daily Devotional Neil Verwey ! ! ! GOD’S FOOTPRINT IN THE MEDIA A Daily Devotional ! By Neil Verwey ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! God’s Footprint in the Media A Daily Devotional ! © 2014 by Neil Verwey, Japan Mission 7-40 Monzen Cho, Ikoma, Nara, Japan 630-0266 Tel: (0)743-73-1754 Fax: (0) 743-73-1681 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.japanmission.org ! ! Published by ICM Press 983-2 Tawaraguchi-cho, Ikoma Nara, Japan 630-0243 ! Cover design by SonShine Works ! ISBN 978-0-900748-53-0 ! ! Scripture citations are from The Holy Bible, New King James Version (NKJV) Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright ©1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. New International Reader’s Version (NIrV) Copyright © 1996, 1998 by Biblica. The Living Bible (TLB) copyright © 1971 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved. Contemporary English Version (CEV) Copyright © 1995 by American Bible Society. The Holy Bible, English Standard Version (ESV), copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. The Holy Bible, King James Version (KJV) by Public Domain. The Holy Bible, New Living Translation (NLT) Copyright© 1996, 2004, 2007 by Tyndale House Foundation. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers Inc., Carol Stream, Illinois 60188. All rights reserved. The Message (TMSG) Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group. Used by permission. All rights reserved. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Acknowledgments Many friends contributed to the completion of this book. -

A Semi-Trapezoidal Tunic with Curved Warp Borders; the Pica-Tarapaca Complex of North Chile (900-1450A.D.) and Strategies of Territorial Control

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2008 Abstracts Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons "Abstracts" (2008). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 286. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/286 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Abstracts A A Semi-Trapezoidal Tunic with Curved Warp Borders; The Pica-Tarapaca Complex of North Chile (900-1450A.D.) and Strategies of Territorial Control Carolina Agüero During the time in the Andes known as the Late Intermediate Period (900-1450 AD), the Tarapacá region was socially integrated with societies that articulated resources from different areas through numerous strategies of exploitation. Dispersed settlements in the region suggest methods of habitation like those known to llama caravan traders. 1 Although it has been explained how, in this period, the Pica-Tarapaca Complex controlled the territory, it has not been studied how the inhabitants of the area understood their common identity. It might be assumed that if identity is recognized as one aspect of sociopolitical connection, then affiliation with the Pica-Tarapaca Complex would be expressed in specific aspects of material culture, in this case, in a shared textile technology. A type of semi-trapezoidal tunic with curved borders is a garment style known to have been used in the Pica-Tarapaca region during the Late Intermediate Period. -

Fashion,Costume,And Culture

FCC_TP_V2_930 3/5/04 3:55 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V2_930 3/5/04 3:55 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 2: Early Cultures Across2 the Globe SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos. -

Cranes, Dragons, and Teddy Bears Japanese Children’S Kimono from the Collection of Marita and David Paly

Cranes, Dragons, and Teddy Bears Japanese Children’s Kimono from the Collection of Marita and David Paly OctobER 22, 2016 – MARCH 26, 2017 PORTLAND ART MUSEUM, OREGON Cranes, Dragons, and Teddy Bears Japanese Children’s Kimono from the Collection of Marita and David Paly occasions called for more extravagant measures: eight garments in this group are miyamairi kimono, one-of-a-kind ceremonial wear made for a toddler’s first visit to a Shinto shrine. These mimic the shape of formal adult kimono and feature family crests and pictorial designs created through a combination of tsutsugaki and hand- painting, or hand-painting alone. Of special interest are the three boys’ kimono with omoshirogara, “novelty designs” that came into vogue in the 1910s through 1930s. Dating from an era when Japan was rapidly modernizing, these robes are decorated with machine-printed images of modernity, such as airplanes and teddy bears. Spanning from the mid-nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, the kimono and banners in this exhibition evoke the magic of childhood in traditional Japan. The Museum is grateful to Marita and David Paly for so generously sharing their collection. David Paly was also an inexhaustible source of information about Japanese textiles and dyeing techniques. Kimono Construction The basic form of the Japanese kimono has changed little over time. Practical and versatile, it is a garment that celebrates the inherent beauty of cloth, uninterrupted by tailoring. An adult kimono is made from a single bolt of fabric, about 14 inches wide and 38 feet long, which is cut into 17 seven straight pieces. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

2 Inventories The Material Culture of Taiko The whole world goes into this drum. —Mark Miyoshi, Japanese American taiko maker, Making American Taiko I understand blackness as always already performed. —Monica L. Miller, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity WHAT’S IN MY BAG Let me show you what’s in my taiko bag. The canvas tote I use to carry all my taiko paraphernalia just gave out after over a decade of use. It’s red and has the distinc- tive TCLA logo silk-screened on one side (see figure 5, the author’s Taiko Center of Los Angeles bag, at http://wonglouderandfaster.com). Luckily, my mother had bought one just like it from my teacher and was kind enough to let me have hers. She didn’t play taiko but was a faithful audience member and supporter. This chapter is not a taiko primer. I know what the early chapters of an ethnog- raphy are supposed to do: the genre dictates that the scene should be set, maps provided, and the histories defined.1 This chapter will not give a tidy overview of, well, anything about taiko. This book will not begin with times past, summaries, or taxonomies. I begin instead with the things closest to me: the things I need to play and the attitudes toward them that I have learned from my friends and teachers. You will learn what’s in my taiko bag: this is an inventory.2 My bag is always full of what I’ll need, plus a lot of detritus from rehearsals and past events.