Franklin D Roosevelt Biography Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C H a P T E R 24 the Great Depression and the New Deal

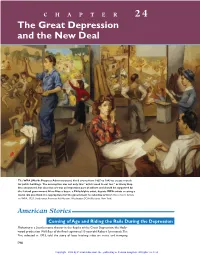

NASH.7654.CP24.p790-825.vpdf 9/23/05 3:26 PM Page 790 CHAPTER 24 The Great Depression and the New Deal The WPA (Works Progress Administration) hired artists from 1935 to 1943 to create murals for public buildings. The assumption was not only that “artists need to eat too,” as Harry Hop- kins announced, but also that art was an important part of culture and should be supported by the federal government. Here Moses Soyer, a Philadelphia artist, depicts WPA artists creating a mural. Do you think it is appropriate for the government to subsidize artists? (Moses Soyer, Artists on WPA, 1935. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC/Art Resource, New York) American Stories Coming of Age and Riding the Rails During the Depression Flickering in a Seattle movie theater in the depths of the Great Depression, the Holly- wood production Wild Boys of the Road captivated 13-year-old Robert Symmonds.The film, released in 1933, told the story of boys hitching rides on trains and tramping 790 NASH.7654.CP24.p790-825.vpdf 9/23/05 3:26 PM Page 791 CHAPTER OUTLINE around the country. It was supposed to warn teenagers of the dangers of rail riding, The Great Depression but for some it had the opposite effect. Robert, a boy from a middle-class home, al- The Depression Begins ready had a fascination with hobos. He had watched his mother give sand- Hoover and the Great Depression wiches to the transient men who sometimes knocked on the back door. He had taken to hanging around the “Hooverville” shantytown south of Economic Decline the King Street railroad station, where he would sit next to the fires and A Global Depression listen to the rail riders’ stories. -

President Roosevelt and the Supreme Court Bill of 1937

President Roosevelt and the Supreme Court bill of 1937 Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hoffman, Ralph Nicholas, 1930- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 09:02:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319079 PRESIDENT ROOSEVELT AND THE SUPREME COURT BILL OF 1937 by Ralph Nicholas Hoffman, Jr. A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of History and Political Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1954 This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made avail able to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without spec ial permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other in stances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: TABLE.' OF.GOWTENTS Chapter / . Page Ic PHEYIOUS CHALLENGES TO THE JODlClMXo , V . -

Mason Williams

City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Mason Williams All Rights Reserved Abstract City of Ambition: Franklin Roosevelt, Fiorello La Guardia, and the Making of New Deal New York Mason Williams This dissertation offers a new account of New York City’s politics and government in the 1930s and 1940s. Focusing on the development of the functions and capacities of the municipal state, it examines three sets of interrelated political changes: the triumph of “municipal reform” over the institutions and practices of the Tammany Hall political machine and its outer-borough counterparts; the incorporation of hundreds of thousands of new voters into the electorate and into urban political life more broadly; and the development of an ambitious and capacious public sector—what Joshua Freeman has recently described as a “social democratic polity.” It places these developments within the context of the national New Deal, showing how national officials, responding to the limitations of the American central state, utilized the planning and operational capacities of local governments to meet their own imperatives; and how national initiatives fed back into subnational politics, redrawing the bounds of what was possible in local government as well as altering the strength and orientation of local political organizations. The dissertation thus seeks not only to provide a more robust account of this crucial passage in the political history of America’s largest city, but also to shed new light on the history of the national New Deal—in particular, its relation to the urban social reform movements of the Progressive Era, the long-term effects of short-lived programs such as work relief and price control, and the roles of federalism and localism in New Deal statecraft. -

CDIR-2018-10-29-VA.Pdf

276 Congressional Directory VIRGINIA VIRGINIA (Population 2010, 8,001,024) SENATORS MARK R. WARNER, Democrat, of Alexandria, VA; born in Indianapolis, IN, December 15, 1954; son of Robert and Marge Warner of Vernon, CT; education: B.A., political science, George Washington University, 1977; J.D., Harvard Law School, 1980; professional: Governor, Commonwealth of Virginia, 2002–06; chairman of the National Governor’s Association, 2004– 05; religion: Presbyterian; wife: Lisa Collis; children: Madison, Gillian, and Eliza; committees: Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs; Budget; Finance; Rules and Administration; Select Com- mittee on Intelligence; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2008; reelected to the U.S. Senate on November 4, 2014. Office Listings http://warner.senate.gov 475 Russell Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–2023 Chief of Staff.—Mike Harney. Legislative Director.—Elizabeth Falcone. Communications Director.—Rachel Cohen. Press Secretary.—Nelly Decker. Scheduler.—Andrea Friedhoff. 8000 Towers Crescent Drive, Suite 200, Vienna, VA 22182 ................................................... (703) 442–0670 FAX: 442–0408 180 West Main Street, Abingdon, VA 24210 ............................................................................ (276) 628–8158 FAX: 628–1036 101 West Main Street, Suite 7771, Norfolk, VA 23510 ........................................................... (757) 441–3079 FAX: 441–6250 919 East Main Street, Richmond, VA 23219 ........................................................................... -

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Mary Mcleod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Final General Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, D.C. Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement _____________________________________________________________________________ Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, District of Columbia The National Park Service is preparing a general management plan to clearly define a direction for resource preservation and visitor use at the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site for the next 10 to 15 years. A general management plan takes a long-range view and provides a framework for proactive decision making about visitor use, managing the natural and cultural resources at the site, developing the site, and addressing future opportunities and problems. This is the first NPS comprehensive management plan prepared f or the national historic site. As required, this general management plan presents to the public a range of alternatives for managing the site, including a preferred alternative; the management plan also analyzes and presents the resource and socioeconomic impacts or consequences of implementing each of those alternatives the “Environmental Consequences” section of this document. All alternatives propose new interpretive exhibits. Alternative 1, a “no-action” alternative, presents what would happen under a continuation of current management trends and provides a basis for comparing the other alternatives. Al t e r n a t i v e 2 , the preferred alternative, expands interpretation of the house and the life of Bethune, and the archives. It recommends the purchase and rehabilitation of an adjacent row house to provide space for orientation, restrooms, and offices. Moving visitor orientation to an adjacent building would provide additional visitor services while slightly decreasing the impacts of visitors on the historic structure. -

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER

Black History Trivia Bowl Study Questions Revised September 13, 2018 B C D 1 CATEGORY QUESTION ANSWER What national organization was founded on President National Association for the Arts Advancement of Colored People (or Lincoln’s Birthday? NAACP) 2 In 1905 the first black symphony was founded. What Sports Philadelphia Concert Orchestra was it called? 3 The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published in what Sports 1852 4 year? Entertainment In what state is Tuskegee Institute located? Alabama 5 Who was the first Black American inducted into the Pro Business & Education Emlen Tunnell 6 Football Hall of Fame? In 1986, Dexter Gordan was nominated for an Oscar for History Round Midnight 7 his performance in what film? During the first two-thirds of the seventeenth century Science & Exploration Holland and Portugal what two countries dominated the African slave trade? 8 In 1994, which president named Eddie Jordan, Jr. as the Business & Education first African American to hold the post of U.S. Attorney President Bill Clinton 9 in the state of Louisiana? Frank Robinson became the first Black American Arts Cleveland Indians 10 manager in major league baseball for what team? What company has a successful series of television Politics & Military commercials that started in 1974 and features Bill Jell-O 11 Cosby? He worked for the NAACP and became the first field Entertainment secretary in Jackson, Mississippi. He was shot in June Medgar Evers 12 1963. Who was he? Performing in evening attire, these stars of The Creole Entertainment Show were the first African American couple to perform Charles Johnson and Dora Dean 13 on Broadway. -

Eleanor Roosevelt: a Voice for Human Rights 3

EEleanorleanor RRoosevelt:oosevelt: A VoiceVoice forfor HumanHuman RightsRights 3 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Describe the life and contributions of Eleanor Roosevelt Identify the main causes for which Eleanor Roosevelt fought during her lifetime Explain the term discrimination Explain the concepts of civil rights and human rights Explain that Eleanor Roosevelt was married to President Franklin Roosevelt Identify Eleanor Roosevelt as a First Lady Identify the Great Depression as a diff cult time in American history Explain the role of the United Nations in the world Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Describe how words and phrases supply meaning in a free verse poem about Eleanor Roosevelt (RL.2.4) Interpret information from a timeline associated with “Eleanor Roosevelt: A Voice for Human Rights,” and explain how the timeline clarif es information in the read-aloud (RI.2.7) 42 Fighting for a Cause 3 | Eleanor Roosevelt: A Voice for Human Rights © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Plan, draft, and edit a free verse poem in which they provide their opinion about Eleanor Roosevelt’s achievements (W.2.1) With assistance, organize facts and information from “Eleanor Roosevelt: A Voice for Human Rights” into a timeline to answer -

Exten,Sions O·F Remark.S Hon. Ralph Yarborough

February 16, 1970 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 3443 Aerographer James R. Dunlap George E. Meacham AMBASSADORS Joe E. McKinzie Morris E. Elsen Charles G. Morgan Jerome H. Holland, of Virginia, to be Am Clifford A. Froelich James D. Palmer bassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Photographer John W. Gebhart John W. Pounds, Jr. of the United States of America to Sweden. Kenneth R. Kimball William C. Griggs Ronald W. Robillard Robert Strausz-Hupe, of Pennsylvania, to Donald F. Sheehan Oran L. Houck Allen R. Shuff be Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipo Joseph A. Hughes Kenneth M. St. Clair, tentiary of the United States of America to Civil Engineer Corps Paul B. Jacovelli Jr. Ceylon, and to serve concurrently and with Jerry G. Havner David H. Kellner Gerard R. Steiner out additional compensation as Ambassador Cecil W. Lovette, Jr. Marlene Marlitt Harold B. St. Peter Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the Warrant Officer Edward G. Torres to be a *Michael T. Marsh Ronald J. Uzenoff United States of America to the Republic permanent chief warrant officer W-3 in the John A. Mattox Jerry E. Walton of Maldives. Joseph E. McClanahan Ervin B. Whitt, Jr. Navy in the classification of electrician, sub IN THE DIPLOMATIC AND FOREIGN SERVICE ject to the qualification therefor as provided James W. McHale William J . York Charles A. McPherronJohn A. Zetes The nominations beginning Keith E. Adam· by law. son, to be a Foreign Service information offi Warrant Officer Charles L. Boland, Jr., to •John A. Balikowski (civilian college gradu be a permanent chief warrant officer W-4 in ate) to be a permanent Lieutenant and a cer of class 1, and ending Harvey M. -

Lunga Vita Al Sud!

LUNGA VITA AL SUD! (O come il Sud riuscì a vincere la guerra). POD: Nel 1862 il generale confederato Robert Lee marciò verso Nord, invadendo Maryland e Pennsylvania, prendendo completamente di sorpresa l’esercito nordista. Tuttavia un messaggero sudista che stava trasportando tutti i piani di Lee smarrì la strada e venne catturato e questo permise a McClellan d’intercettarlo con la battaglia di Antieman. Ma cosa sarebbe successo se quel messaggero non fosse stato catturato? 1860: in novembre, al termine di una confusa campagna elettorale con il Partito Democratico spaccato in due tra abolizionisti e schiavisti, il repubblicano Abraham Lincoln vince le elezioni sui democratici Stephen Douglas e John Breckinridge. Il 20 dicembre, con la secessione della Sud Carolina, inizia la secessione degli Stati Confederati. 1861: Il senatore del Missouri Jefferson Davis è eletto presidente provvisorio degli Stati Confederati d’America(Confederates States of America o CSA), con capitale Richmond. Il 12 aprile truppe sudiste attaccano Fort Sumter, al largo di Charleston in Sud Carolina, dando così via alla guerra d’indipendenza. Lincoln, insediatosi il 4 marzo, invia 75 000 uomini guidati dal generale George McClellan a invadere la Virginia ma questi sono sconfitti a Bull Run dal generale Robert Lee. George McClellan, considerato uno dei peggiori generali americani di sempre. 1862: Tra l’8 e il 9 marzo le truppe nordiste non riescono a prendere Richmond, capitale della Confederazione, mentre la USS Monitor e la CSS Virginia si cannoneggiano ad Hampton Roads. Il 25 aprile l’ammiraglio David Ferragut occupa New Orleans ma il 25 giugno Lee lancia la Controffensiva dei 7 giorni e espelle i nordisti dalla Virginia. -

Organizing Principle 5: the Great Depression and World War II 5

Organizing Principle 5: The Great Depression and World 5 weeks / Second Nine Weeks War II Reporting Categories: Global Military, Political, and Economic Challenges 1890-1940 The United States and the Defense of the International Peace 1940- present Measurement Topic: The Great Depression and New Deal Benchmarks Curriculum Standards Students Will: Academic Language SS.912.A.5.11 • Examine the causes, course, and - Recognize the cause-and- The Great Depression: buying on margin, bull/bear consequences of the Great Depression effect relationships of market, Dow Jones Industrial Average, Bonus Army, and the New Deal. economic trends as they relate Black Tuesday, Hawley-Smoot Tariff, Herbert Hoover, to society in the United States Hooverville, “Hoover Flag,” Agriculture Adjustment Act (AAA), First Hundred Days, Franklin D. during the 1920s and 1930s. • Examine key events and people in Roosevelt, Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Dust SS.912.A.5.12 Florida history as they relate to Bowl, Okies, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation United States history. - Identify and/or evaluate the (FDIC), Gross National Product (GNP), Public Works impact of business practices, Administration (PWA), National Labor Relations Act consumer patterns, and (Wagner Act), National Recovery Act, National government policies of the Recovery Administration, New Deal, “Recovery, 1920s and 1930s as they relate Reform, Relief,” Social Security Act, Tennessee Valley to the Great Depression and Authority (TVA), Works Progress Administration subsequent New Deal. (WPA), Court Packing Plan, Huey Long, Charles Coughlin, fireside chats, Eleanor Roosevelt, Glass- - Examine the human Steagall Act, “Black Cabinet”, Mary McLeod Bethune, experience during both the socialism, speculation boom, Bank Holiday, Dorthea Lange/ “Migrant Mother”, impact of climate and Great Depression and the New natural disasters Deal. -

Congressional Record

March 5, 2021 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S1219 with school closures but only if they town admitting that they have written Senate agreed to the motion to proceed are Federal employees. To all the par- ‘‘the most progressive domestic legisla- to consideration of the bill. ents without government jobs, no such tion in a generation.’’ That is the A unanimous-consent-time agree- luck. White House Chief of Staff. Meanwhile, ment was reached providing for further There are provisions to let abortion here in the Senate, Democrats are still consideration of the bill at approxi- providers raid the small business res- pretending this is some down-the-mid- mately 9 a.m., on Friday, March 5, 2021; cue funds that were meant for Main dle proposal and lecturing us for not that there be 3 hours of debate remain- Street businesses. supporting it. They can’t even get their ing, with the time equally divided and They want to pay people a bonus not stories straight. controlled between the two managers to go back to work when we are trying The administration campaigned on or their designees; and that it be in to rebuild our economy. ushering in a new day of unity and bi- order for Senator SANDERS to offer the There is an effort to create a partisanship, but in 2020, under Repub- first amendment. brandnew, sprawling cash welfare pro- lican leadership, the Senate negotiated The ACTING PRESIDENT pro tem- gram—not the one-time checks but five rescue bills totaling $4 trillion, pore. The Senator from Vermont. constant payments—that ignores the and none of them got fewer than 90 UNANIMOUS CONSENT AGREEMENTS pro-work lessons of bipartisan welfare votes. -

Minutes of the Senate Democratic Conference

MINUTES OF THE SENATE DEMOCRATIC CONFERENCE 1903±1964 MINUTES OF THE SENATE DEMOCRATIC CONFERENCE Fifty-eighth Congress through Eighty-eighth Congress 1903±1964 Edited by Donald A. Ritchie U.S. Senate Historical Office Prepared under the direction of the Secretary of the Senate U.S. Government Printing Office Washington 105th Congress S. Doc. 105±20 U.S. Government Printing Office Washington: 1998 Cover illustration: The Senate Caucus Room, where the Democratic Conference often met early in the twentieth century. Senate Historical Office. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Senate Democratic Conference (U.S.) Minutes of the Senate Democratic Conference : Fifty-eighth Congress through Eighty-eighth Congress, 1903±1964 / edited by Donald A. Ritchie ; prepared under the direction of the Secretary of the Senate. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. United States. Congress. SenateÐHistoryÐ20th centuryÐSources. 2. Democratic Party (U.S.)ÐHistoryÐ20th centuryÐSources. I. Ritchie, Donald A., 1945± . II. United States. Congress. Senate. Office of the Secretary. III. Title. JK1161.S445 1999 328.73'07657Ðdc21 98±42670 CIP iv CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................................................... xiii Preface .......................................................................................... xv Introduction ................................................................................. xvii 58th Congress (1903±1905) March 16, 1903 ....................................................................