Celtic Mythology and Religion Pdf, Epub, Ebook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

A Guide to Ten of the Best Pictish Symbol Stones in Aberdeenshire

Pictish Symbol Stones The Pictish Period 300 AD – 900 AD MAIDEN STONE ST PETER’S CHURCH, FYVIE As one of the heartlands of the Pictish community, Aberdeenshire is home to a large The origin of the Picts can be found in the tribal society of the Iron Age. Their society was number of the elaborately decorated Symbol Stones for which the Picts are famed – around hierarchical, with a warrior elite and a lower farming class. They lived in Scotland, North of PICARDY STONE 20% of all Pictish stones recorded in Scotland can be found in Aberdeenshire. the Forth and Clyde rivers, between the 4th and 9th Centuries AD, with a particularly strong presence in what is now Aberdeenshire. This can be seen in the frequent occurrence of place The stones, incised or carved in relief, are decorated with a variety of symbols, ranging from names beginning “Pit”, thought to indicate the site of a Pictish settlement, as well as the BRANDSBUTT geometric shapes and patterns, to animals (real and mythical), human figures, objects, evidence from the archaeological record such as Symbol Stones and fortifications. and Christian motifs. Some earlier Pictish stones are also incised with a script known as Ogham, which comprises a pattern of short linear strokes crossing a vertical line. Said to They acquired the name Pict, or Picti, meaning “Painted People”, from the Romans – indeed, have originated around the 4th Century AD, it is an early form of the Irish language. Most much of what is known of the Picts is derived from historical writers from outside of examples of Ogham inscriptions are thought to represent personal names. -

K 03-UP-004 Insular Io02(A)

By Bernard Wailes TOP: Seventh century A.D., peoples of Ireland and Britain, with places and areas that are mentioned in the text. BOTTOM: The Ogham stone now in St. Declan’s Cathedral at Ardmore, County Waterford, Ireland. Ogham, or Ogam, was a form of cipher writing based on the Latin alphabet and preserving the earliest-known form of the Irish language. Most Ogham inscriptions are commemorative (e.g., de•fin•ing X son of Y) and occur on stone pillars (as here) or on boulders. They date probably from the fourth to seventh centuries A.D. who arrived in the fifth century, occupied the southeast. The British (p-Celtic speakers; see “Celtic Languages”) formed a (kel´tik) series of kingdoms down the western side of Britain and over- seas in Brittany. The q-Celtic speaking Irish were established not only in Ireland but also in northwest Britain, a fifth- THE CASE OF THE INSULAR CELTS century settlement that eventually expanded to become the kingdom of Scotland. (The term Scot was used interchange- ably with Irish for centuries, but was eventually used to describe only the Irish in northern Britain.) North and east of the Scots, the Picts occupied the rest of northern Britain. We know from written evidence that the Picts interacted extensively with their neighbors, but we know little of their n decades past, archaeologists several are spoken to this day. language, for they left no texts. After their incorporation into in search of clues to the ori- Moreover, since the seventh cen- the kingdom of Scotland in the ninth century, they appear to i gin of ethnic groups like the tury A.D. -

The Pictish Race and Kingdom Author(S): James Ferguson Source: the Celtic Review, Vol

The Pictish Race and Kingdom Author(s): James Ferguson Source: The Celtic Review, Vol. 7, No. 25 (Feb., 1911), pp. 18-36 Published by: Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30070376 Accessed: 13-03-2016 17:12 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 147.8.31.43 on Sun, 13 Mar 2016 17:12:53 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 18 THE CELTIC REVIEW THE PICTISH RACE AND KINGDOM JAMES FERGUSON I AOONG the obscure periods in history, there is none more alluring or more tantalising in the absence of authentic records than the two hundred years which followed the with- drawal of the Roman legions from the northern walls, and submerged an advanced state of civilisation in Britain under the waves of barbarian invasions. 'The frontier,' wherever it may be, always exercises a powerful.charm on the imagina- tion, but nowhere is the spell more felt than where the rude Roman eagle, carved on the native rock, faces the un- conquered shores of Fife, and on the long line of the fortified limes from the narrowing Firth to below the Fords of Clyde the legionary gazed across the central depression of Scotland to the Caledonian forest and the untamed Highland hills. -

The Celtic Encyclopedia, Volume V

7+( &(/7,& (1&<&/23(',$ 92/80( 9 T H E C E L T I C E N C Y C L O P E D I A © HARRY MOUNTAIN VOLUME V UPUBLISH.COM 1998 Parkland, Florida, USA The Celtic Encyclopedia © 1997 Harry Mountain Individuals are encouraged to use the information in this book for discussion and scholarly research. The contents may be stored electronically or in hardcopy. However, the contents of this book may not be republished or redistributed in any form or format without the prior written permission of Harry Mountain. This is version 1.0 (1998) It is advisable to keep proof of purchase for future use. Harry Mountain can be reached via e-mail: [email protected] postal: Harry Mountain Apartado 2021, 3810 Aveiro, PORTUGAL Internet: http://www.CeltSite.com UPUBLISH.COM 1998 UPUBLISH.COM is a division of Dissertation.com ISBN: 1-58112-889-4 (set) ISBN: 1-58112-890-8 (vol. I) ISBN: 1-58112-891-6 (vol. II) ISBN: 1-58112-892-4 (vol. III) ISBN: 1-58112-893-2 (vol. IV) ISBN: 1-58112-894-0 (vol. V) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mountain, Harry, 1947– The Celtic encyclopedia / Harry Mountain. – Version 1.0 p. 1392 cm. Includes bibliographical references ISBN 1-58112-889-4 (set). -– ISBN 1-58112-890-8 (v. 1). -- ISBN 1-58112-891-6 (v. 2). –- ISBN 1-58112-892-4 (v. 3). –- ISBN 1-58112-893-2 (v. 4). –- ISBN 1-58112-894-0 (v. 5). Celts—Encyclopedias. I. Title. D70.M67 1998-06-28 909’.04916—dc21 98-20788 CIP The Celtic Encyclopedia is dedicated to Rosemary who made all things possible . -

Celtic Clothing: Bronze Age to the Sixth Century the Celts Were

Celtic Clothing: Bronze Age to the Sixth Century Lady Brighid Bansealgaire ni Muirenn Celtic/Costumers Guild Meeting, 14 March 2017 The Celts were groups of people with linguistic and cultural similarities living in central Europe. First known to have existed near the upper Danube around 1200 BCE, Celtic populations spread across western Europe and possibly as far east as central Asia. They influenced, and were influenced by, many cultures, including the Romans, Greeks, Italians, Etruscans, Spanish, Thracians, Scythians, and Germanic and Scandinavian peoples. Chronology: Bronze Age: 18th-8th centuries BCE Hallstatt culture: 8th-6th centuries BCE La Tène culture: 6th century BCE – 1st century CE Iron Age: 500 BCE – 400 CE Roman period: 43-410 CE Post (or Sub) Roman: 410 CE - 6th century CE The Celts were primarily an oral culture, passing knowledge verbally rather than by written records. We know about their history from archaeological finds such as jewelry, textile fragments and human remains found in peat bogs or salt mines; written records from the Greeks and Romans, who generally considered the Celts as barbarians; Celtic artwork in stone and metal; and Irish mythology, although the legends were not written down until about the 12th century. Bronze Age: Egtved Girl: In 1921, the remains of a 16-18 year old girl were found in a barrow outside Egtved, Denmark. Her clothing included a short tunic, a wrap-around string skirt, a woolen belt with fringe, bronze jewelry and pins, and a hair net. Her coffin has been dated by dendrochronology (tree-trunk dating) to 1370 BCE. Strontium isotope analysis places her origin as south west Germany. -

Anglo-Saxons, Picts and Scots Slide3

Anglo-Saxons, Picts and Scots Learning Objective: ! To find out who the Picts and Scots were and where they lived. NEXT www.planbee.com What can you remember about who the Anglo-Saxons were? BACK NEXT www.planbee.com Jutes, Angles and Saxons invaded Britain after the Romans left. ! They came from Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. ! Eventually they became known as the Anglo-Saxons. ! They conquered the Britons who were living in England and pushed them north. ! They settled and set up farms, homes and villages. BACK NEXT www.planbee.com The Anglo-Saxons managed to conquer a large part of Britain but there was one area that they couldn’t conquer straight away. In fact, it took a few hundred years. Where do you think this area might have been? BACK NEXT www.planbee.com Just like the Romans, the Anglo-Saxons were not able to conquer the people living in the north of Britain (in what is now Scotland) because it was settled by two groups of people: ! the Picts and the Scots. Do you know anything about the Picts and Scots? What do you think these groups of people might have been like? BACK NEXT www.planbee.com This map shows where the Picts and Scots lived when the Anglo-Saxons had Picts settled in Britain. You can see the Scots Grampian mountains on this map which acted as a natural barrier between the Picts and the Scots. The Picts had been in this area since the Mesolithic era. The first recorded mention of them was by a Roman writer in the 3rd century AD. -

In My Defence, God Me Defend-Expression, Saying

IN MY DEFENCE, GOD ME DEFEND-EXPRESSION, SAYING CLIMATE THE CLIMATE OF SCOTLAND IS TEMPERATE AND OCEANIC, AND TENDS TO BE VERY CHANGEABLE. IT HAS MUCH MILDER WINTERS AND COOLER WETTER SUMMERS THAN OTHER AREAS IN THE SAME LATITUDE (MOSCOW REGION IN RUSSIA, SOUTHERN SCANDINAVIA). HOWEVER, TEMPERATURES ARE GENERALLY LOWER THAN IN THE REST OF THE UK. IT HAD THE COLDEST EVER UK TEMPERATURE OF -27,2ºc IN THE GRAMPIAN MOUNTAINS ON 11TH FEBRUARY 1895. HEAVY SNOWFALL IS NOT COMMON IN THE LOWLANDS, BUT IT BECOMES MORE COMMON WITH THE ALTITUDE. BRAEMAR HAS AN AVERAGE OF 59 ANOW DAYS PER YEAR WHILE MANY COASTSAL AREAS AVERAGE FEWER THAN 10 DAYS OF LYING SNOW PER YEAR. THE WEST OF SCOTLAND IS USUALLY WARMER THAN THE EAST, OWING TO THE INFLUENCE OF ATLANTIC OCEAN CURRENTS. TIREE IS ONE OF THE SUNNIEST PLACES IN THE COUNTRY. RAINFALL VARIES WIDELY ACROSS SCOTLAND. THE WESTERN HIGHLANDS OF SCOTLAND ARE THE WETTEST. RAINFALL IN A FEW PLACES EXCEEDS 3,000 MM ANNUALLY. THE LOWLANDS RECIEVE LESS THAN 800 MM ANNUALLY. HISTORY: IT STARTED WHEN THE ROMANS OCCUPIED WHAT IS NOW ENGLAND AND WALES, ADMINISTERING IT AS A PROVINCE CALLED BRITANNIA. ROMAN INVASIONS AND OCCUPATIONS OF SOUTHERN SCOTLAND WERE A SERIES OF BRIEF INTERLUDES. ACCORDING TO THE ROMAN HISTORIAN TACITUS, THE CALEDONIANS ATTACKED ROMAN FORTS AND FOUGHT WITH THER LEGIONS, IN A SURPRISE NIGHT-ATTACK. THEY VERY NEARLY WIPED OUT THE WHOLE 9YH LEGION UNTIL IT WAS SAVED BY AGRICOL’AS CAVALRY. THE ROMANS ERECTED HADRIAN’S WALL TO CONTROL TRIBES ON BOTH SIDES OF THE WALL, AND THAT WAS THE NORTHERN BORDER OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE. -

Complexity of Celtic Culture and Museum Practices

Complexity of Celtic Culture and Museum Practices Shannon Eileen Barry University of Oregon Masters in Arts Management 2014-2016 Research Capstone Barry, 1 Abstract: Presenting cultural communities in museums is challenging. Each of these groups has nuances that make them difficult to accurately display in an exhibit. I chose to look at this particular issue through the lens of Celtic culture. To be able to display Celtic culture in museums, those creating an exhibit need to have certain knowledge. Most people assume that the Celts only inhabited the British Isles, as they are most associated with that region today. In fact, the Celts emerged in what is now central Austria. Their history was one of expansion and movement. At its farthest, there were Celtic settlements from Turkey to Spain, yet the Celts were never a single, unified kingdom. This complicated history leads to a debate among scholars about how to define the term ‘Celt.’ Popular opinions include arguments that the Celts are a genetic group, a linguistic group, an artistic style, or a cultural group with shared beliefs and practices. Another important discussion that surfaces while researching these varied definitions is the ‘Anti-Celt’ idea, which argues that the term is not broad enough to describe the numerous Celtic groups spread across Europe. After gaining an understanding of Celtic culture by exploring its history and definitions, this knowledge can be incorporated into the phases of creating an exhibit – planning, display, text (writing and interpretation), and evaluation. All of this information comes together to create a strategic process for museums to implement a comprehensive exhibition on Celtic culture. -

Pictish Ogam Stones As Representations of Cross-Cultural Dialogue

Pictish Ogam Stones as Representations of Cross-cultural Dialogue Pictish Ogam Stones as Representations of Cross-cultural Dialogue Kathryn M. Hudson & Wayne E. Harbert The Pictish Ogham stones of eastern Scotland represent an interpretive conundrum. Their inscriptions visually match their Irish counterparts but do not align with traditional conventions of use, and the juxtaposition of foreign script and indigenous symbol suggests an ancient dialogue rooted in the visual register. This paper presents a survey of these stones and situates them in a broader archaeological and historical context. Their role as reflectors of a core-periphery mode of interaction and documents of cultural negotiation is considered, and their position in a changing cultural landscape is evaluated. Institute for European and Mediterranean Archaeology 1 Kathryn M. Hudson & Wayne E. Harbert Introduction Details of the emergence of the Pictish confederation – an admittedly problematic The Picts, as agents of a rich but term that nonetheless appears to accurately perennially perplexing and ill-understood reflect Pictish social organization – remain symbolic culture, confront linguists uncertain. Whatever its origins, the Pictish and archaeologists with a wealth of confederation is generally believed to have conundrums. No objects exemplify these encompassed multiple distinct kingdoms.3 problems more than the so-called Pictish The Poppleton Manuscript contains a ogam inscriptions. These inscriptions kinglist and sociopolitical observations visually match their Irish counterparts but that have been used to propose multiple do not align with traditional conventions of Pictish kingdoms;4 the Gaelic quatrains use, and the juxtaposition of foreign script in Lebor Bretnach as well as assorted Irish and indigenous symbol suggests an ancient legends have also been used in support dialogue rooted in the visual register. -

A Genetic Signal of Central European Celtic Ancestry: Preliminary Research Concerning Y-Chromosomal Marker S28 (Part 2)

A Genetic Signal of Central European Celtic Ancestry: Preliminary Research Concerning Y-Chromosomal Marker S28 (Part 2) Hallstatt Culture: 720 to 600 BC and 600 BC to 480 BC (Ha C and D) This interval represents a time of major changes in Europe, in the regions once characterized by the Pfyn and related cultures with roots extending back to the Neolithic, and the Urnfield groups which would morph into the peoples of the Hallstatt tradition with their characteristic elite burials. Artist rendition of typical rich Hallstatt inhumation burials Kristiansen (1998) proposes that the movement of Hallstatt C warrior elite spread across Central and Western Europe, at a time when trade routes to the north diminished. However those in the eastern tier maintained links to the Lusatian culture and the Baltic regions, with a continued emphasis on trade in amber and mining of salt in the immediate surrounds of Hallstatt in Austria. Hallstatt is actually at the southeastern tip of what was a very large oval shaped territory with the center of gravity northwest of the Alps. In Reinecke’s system of dating, this period is known as Hallstatt C and D. Hallstatt C (earliest phase) is characterized by rich horse and wagon burials (containing ornate horse tack) and includes the region from western Hungary to the Upper Danube. Hallstatt D is represented by a chiefdom zone and elite burials further to the west, with settlements concentrated near the headwaters of every major river from the Loire, to the Seine, Rhone, Rhine and Danube. The geographical re-alignment was likely a function of the establishment of a Greek (Phoecian) trading center in Massilia (Marseilles), circa 600 BC. -

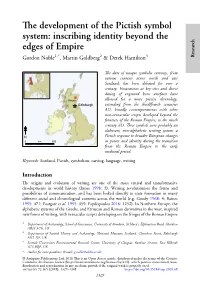

The Development of the Pictish Symbol System: Inscribing Identity Beyond the Edges of Empire

The development of the Pictish symbol system: inscribing identity beyond the edges of Empire Gordon Noble1,*, Martin Goldberg2 & Derek Hamilton3 Research The date of unique symbolic carvings, from various contexts across north and east Scotland, has been debated for over a century. Excavations at key sites and direct dating of engraved bone artefacts have Rhynie allowed for a more precise chronology, Edinburgh extending from the third/fourth centuries AD, broadly contemporaneous with other non-vernacular scripts developed beyond the frontiers of the Roman Empire, to the ninth century AD. These symbols were probably an elaborate, non-alphabetic writing system, a N Pictish response to broader European changes 0km 500 in power and identity during the transition from the Roman Empire to the early medieval period. Keywords: Scotland, Pictish, symbolism, carving, language, writing Introduction The origins and evolution of writing are one of the most critical and transformative developments in world history (Innes 1998: 3). Writing revolutionises the forms and possibilities of communication, and has been linked directly to state formation in many different social and chronological contexts across the world (e.g. Goody 1968: 4; Baines 1995: 471; Postgate et al. 1995: 459; Papdopoulos 2016: 1252). In Northern Europe, the alphabetic systems of the Greeks, and Etruscan and Roman derivatives in the west, inspired new forms of writing, with vernacular scripts developing on the fringes of the Roman Empire 1 Department of Archaeology, School of Geosciences,