University of Copenhagen 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Møbler Dk De Døde Idéer F.C. København

ARKITEKTUR KULTUR BYLIV DESIGN AKTIVITETER INTERVIEW Jokum Rohde - ... og de mørke opgange TOP+FLOP Københavnersteder - Mikael Bertelsen NR 09 · APRIL 2006 UPDATE Copenhagen Dome - Kæmpehal til København? OLD SCHOOL Rådhuspladsen - Fra voldgrav til centrum MØBLER DK Hvem kommer ud af Jacobsens æg? GRATIS DE DØDE IDÉER F.C. KØBENHAVN Da København dræbte Er FCK fans café latte typer, Manhattan og Eiffeltårnet. og kan holdet noget i Europa? VELKOMMEN TIL VIASATS DIGITALE VERDEN Med din nye digitale parabolmodtager og de over 50 digitale kanaler er underholdningen derhjemme sikret langt ud i fremtiden. Du bliver vidne til de største filmpremierer, hele TV3s verden og de mest intense fodboldkampe som finalerne i Champions League og FA Cup’en. Og så selvfølgelig alle 198 SAS Liga-kampe DIREKTE! ©Disney SAS-Liga Solkongen Junglebogen 2 VIASAT GULD 52 digitale kanaler. Pris før 299 kr. NU KUN 199 kr. NYHED Digital TV-box – værdi 999 kr. TV2, DR1 og DR2 i digital kvalitet* *Forudsætter oprettelse af et Guld-årsabon. på Viasats alm. vilkår. Pris 1. år 199 kr./md. + kortafgift og oprett.gebyr til i alt 679 kr. .+ mini parabol til 795 kr. – samlet 3.862 kr. Herefter Viasats til enhver tid gældende normalpris. Kun v/ tilmelding til Betalingsservice og kun husstande uden digitalt Viasat-abon. de seneste 6 mdr. Tilbudet gælder en begrænset periode. Digital parabolmodtager uden abon. 2.095 kr., lev. og installation normalpris 1.000 kr. Digital TV-box normalpris uden køb af Viasat abonnement 999 kr. Boxen gør det muligt at se en række andre kanaler, du ikke modtager fra Viasat, i ægte digital kvalitet, fx TV2. -

Metropol 2020, Nr. 1

METROPOL 2020, NR. 1 Fra fæstningsby til Øresundsmetropol Af Henning Bro Som afsæt til videre forskning i hovedstads- og øresundsområdets regionale historie sætter denne artikel fokus på, hvorledes Nordøstsjælland i store træk udvikle sig til en af landets mest integrerede regioner. Således de lange linjer fra middelalderens sundbyer, over enevældens total dominerende hovedstad, til dannelsen af hovedstadsmetropolen op gennem det 20. århundrede og dennes begyndende sammensmeltning med byer og landskaber øst for Øresund efter årtusindeskiftet. Fæstningsbyen og dens opland – tiden før 1850 Fra vikingetiden og op gennem middelalderen udvikledes det danske bysystem først i form af selvgroede og senere kongeanlagte indlandsbyer og siden kongeanlagte kystbyer i 1100- og 1200- tallet og i den sidste del af perioden. Byerne blev tidligt omfattet af kongemagtens interesse og udskilt som særlige administrations- og skatteområder direkte under kronen, der yderligere øgede indtægterne fra byerne ved senere tildeling af købstadsprivilegier: En vis form for bymæssigt selvstyre, egen jurisdiktion og eneret til handel og håndværk i en radius af 1-4 mil. Oveni dette vækstgrundlag kom så de rigdomme, som kirkemagten samlede omkring købstædernes kirker og klostre, og den administration af by og opland, som udgik fra de kronborge, som en betydelig del af byerne lå i ly af, og som her ydede yderligere beskyttelse ud over den, som eventuelle bymure, palisadeværker og voldegrave gav. Købstæderne blev bundet sammen i et system og det centrale omdrejningspunkt i den feudale økonomi i form af: Formidling af varestrømme mellem by og opland, administrative og kulturelle serviceydelser til oplandet og modtagelse og videregivelse af varer og tilsvarende ydelser til og fra andre og større købstæder. -

The Anglo-Danish Society Newsletter

THE ANGLO-DANISH SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Autumn 2021 www.anglo-danishsociety.org.uk Reg. Charity No 313202 The Royal Yacht Dannebrog in London 2012 PHOTO : Palle Baggesgaard Pedersen THE ANGLO-DANISH SOCIETY Dear Members & Friends Patrons Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II The Covid-19 restrictions regarding social interaction sadly meant that Her Majesty Queen Margrethe II some of our proposed past events were cancelled. We remain optimistic that we can again meet friends and members at the Ambassador’s Protector of the Scholarship Programme Reception in September. You will also be able to meet some of our HRH the Duchess of Gloucester, GCVO scholars. Honorary Presidents The Tower of London Dinner in October, the Georg Jensen shopping HE Lars Thuesen, R1, Danish Ambassador event in November and The Danish Church Christmas event in December will hopefully also take place as planned. These are all popular events. Officers and Members of Council There may well be a refreshing change ahead to events on offer as two Wayne Harber, OBE, K (Chairman) new council members elected to council in June, Cecilie Mortensen and Peter Davis, OBE (Vice Chairman) Louisa Greenbaum, will oversee Event Management in future. Alan Davey, FCMA (Hon. Treasurer) Bette Petersen Broyd (Hon. Secretary) At the AGM in June Kristian Jensen, who already serves on the Katie Schwarck (Hon. Scholarship Scholarship Committee, was elected to council with responsibility for Secretary) Heritage. We envisage that Kristian will oversee the mapping of the Palle Baggesgaard Pedersen, R nearly 100 years since The Anglo-Danish Society was formed in 1924. Christine Bergstedt Queen Alexandra offered her encouragement in the formation of the Dr. -

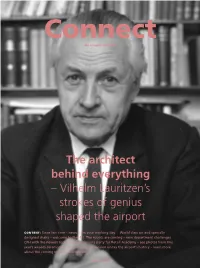

The Architect Behind Everything – Vilhelm Lauritzen's Strokes of Genius Shaped the Airport

An insight into CPH The architect behind everything – Vilhelm Lauritzen’s strokes of genius shaped the airport CONTENT: Since last time – news from your working day | World class art and specially designed chairs – welcome to Pier E | The robots are coming – new department challenges CPH with the newest technology | Diploma party for Retail Academy – see photos from this year’s awards ceremony | New terminal expansion unites the airport’s history – learn more about the coming major building work June | 2019 Connect Connect is published four times yearly by Copenhagen Airport for employees and concessionnaires/ tenants of stores and eateries in CPH. Connect writes about new trends in retail and travel retail and focuses on overall development of the airport. In addition, Connect also gives readers insight into everyday life in CPH: the dedicated employees, the happy travelers, and everything surprising and innovative that takes place daily in Denmark's biggest workplace. Editor in chief Pia Jeanette Lynggaard Editor Henriette Koustrup Madsen Dear Reader, Journalist Julie Elver It was wonderful to meet so many of you at the Diploma party Photographer in the VL-Terminal at the end of May. Many, many thanks for a Andreas Bro fantastic evening and for making me feel so welcome. It was a Morten Langkilde / Ritzau Scanpix pleasure to see so many new faces and to celebrate you properly. PR Many thanks, too, for your daily efforts for our multitude of guests. This is one of the reasons that Copenhagen Airport won Art Director Mathias Ambus the award for Northern Europe’s best airport at this year’s Skytrax Awards in March. -

Tilgængelighedsplan 2016

Tilgængelighedsplan 2016 UDKAST Indholdsfortegnelse Indholdsfortegnelse 1 Forord ......................................................... 4 2 Indledning .................................................... 5 3 Tilgængelighed generelt .................................. 6 3.1 Brugerne og deres udfordringer ..................................6 3.2 Gode tilgængelighedsløsninger...................................8 3.2.1 Gangbaner ...............................................................8 3.2.2 Busstoppesteder .....................................................11 3.2.3 Kryds ....................................................................12 3.2.4 Ramper og trapper ..................................................13 4 Tilgængelighedsnettet ...................................16 4.1 Rejsemål ................................................................16 4.2 Ruter .....................................................................17 5 Eksisterende barrierer ...................................22 5.1 Gangbaner .............................................................23 5.2 Busstoppesteder .....................................................24 5.3 Fodgængerkrydsninger ............................................25 5.4 Øvrige ...................................................................26 6 Prioritering ..................................................28 6.1 Gennemførte tilgængelighedstiltag ............................30 6.2 Anbefaling og prioritering ........................................31 7 Handlingsplan ..............................................32 -

Kommuneplan 2021 Frederiksbergs Plan for En Bæredygtig Byudvikling Kommuneplan 2021

] [FORSLAG REDEGØRELSE KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 FREDERIKSBERGS PLAN FOR EN BÆREDYGTIG BYUDVIKLING KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 Forsidefoto: Frederiksberg Hospital, hovedindgangen. 2 | REDEGØRELSE | KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 INDHOLD INDLEDNING ......................................................................... 5 HIDTIDIG PLANLÆGNING OG UDVIKLING ................................ 6 BEFOLKNINGSUDVIKLING ...................................................... 14 BOLIGER OG BOLIGTILVÆKST ................................................. 19 BYUDVIKLING OG LOKALISERING ............................................ 25 BÆREDYGTIG BYUDVIKLING OG KLIMA ................................... 26 GRØN STRUKTUR .................................................................. 34 MILJØBESKYTTELSE ............................................................... 38 MOBILITET ............................................................................ 46 UDDANNELSE ....................................................................... 47 ERHVERV .............................................................................. 48 DETAILHANDEL ..................................................................... 50 BEVARINGSVÆRDIGE BYGNINGER ........................................... 67 KULTURMILJØER ................................................................... 69 KOMMUNEPLANENS FORHOLD TIL ANDEN PLANLÆGNING ....... 90 REDEGØRELSE | KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 | 3 KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 4 | REDEGØRELSE | KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 KOMMUNEPLAN 2021 INDLEDNING HVAD ER EN KOMMUNEPLAN? En kommuneplan -

Onecollection-Finnjuhl.Pdf

ILQQMXKOLQGG 30 ILQQMXKOLQGG 30 ILQQMXKOLQGG 30 For further information please see www.onecollection.com Here you will find all information in Danish and English, 1000 high resolution images for download, references, news, press releases and soundslides... You are always welcome to call us at +45 70 277 101 or send an e-mail to [email protected] Please enjoy! Model 137 Tray Table Baker Sofa Wall Sofa Model 109 Ross Model 46 Model 500 Model 57 The Poet Chieftains Chair Model 108 The Pelican Model 45 Eye Table ILQQMXKOLQGG 30 Finn Juhl is regarded Finn Juhl was born January 30th 1912 at as the father of "Danish Frederiksberg as son of cloth merchant Johannes Juhl and his German born wife, who unfortunately Design" and became died three days after the birth of little Finn. world famous after he He grew up together with his two years older brother designed the Trusteeship Erik Juhl and their authoritarian father in a home Council in the UN with Tudor and Elizabethan dinning room, leaded windows and tall panels. building. Originally Finn Juhl wanted to become an art historian but his father persuaded him to join The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture after his graduation in 1930. During the Summer of 1934 Finn Juhl had a job with the architect Vilhelm Lauritzen and at the school he chose classes with Professor Kay Fisker, who was a brilliant lecturer whose lectures always were a draw. In 1931 Kay Fisker had, along with Povl Stegmann and C.F. Møller, won the competition concerning The University of Århus and created a Danish vision of the international functionalism, which was much admired, not at least by his students. -

Important Nordic Design Curated by Lee F Mindel, Faia, of Shelton, Mindel & Associates Totals £2,256,200/$3,558,027

IMPORTANT NORDIC DESIGN CURATED BY LEE F MINDEL, FAIA, OF SHELTON, MINDEL & ASSOCIATES TOTALS £2,256,200/$3,558,027 WORLD RECORDS FOR POUL HENNINGSEN, AXEL SALTO, VILHELM LAURITZEN, KAJ GOTTLOB AND ORLA MØLGAARD-NIELSEN AND PETER HVIDT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE London – Phillips de Pury & Company’s Important Nordic Design auction totaled £2,256,200/$3,558,027 selling 70% by value and 72% by lot. The top lot of the sale was an Exceptional and large ‘Spiral’ wall light, for the Scala cinema and concert hall, Århus Theatre by Danish lighting designer, Poul Henningsen , selling for an Artists World Record £253,250 /$399,375 double its estimate. Poul Henningsen’s , ‘The house of the future’ ceiling light went for £193,250/$304,755 , a rare monumental vase in the ‘budding’ style by Axel Salto sold for £79,250/$124,977 and the Vilhelm Lauritzen Sofa for the Radiohuset, Frederiksberg achieved £70,850 /$111,730. There was fierce competition on the phone banks for a Pair of standard lamps by Finnish Designer, Paavo Tynell . The lot, which was estimated to achieve £4,000 - £6,000 sold for £32,450/$51,173.65, eight times its estimated value. The active bidding in the room and on the phone banks from international buyers reflected the strength of the Design Market. The sale offered more than the usual suspects, showing the depth of the market for Nordic Design and for works with exceptional provenance and of rare forms. “The most gratifying thing about this Phillips de Pury exhibition is that it was a museum show that surpassed anything that we could have imagined. -

Kulturelle Faciliteter Cultural Facilities

KULTURELLE FACILITETER CULTURAL FACILITIES Kulturelle faciliteter Cultural facilities Lys, der er tilpasset rummets funktion og arkitektur, giver Most cultural facilities demand a lighting scheme, which en behagelig og kvalitativ oplevelse. both supports functional needs and invites an aesthetic response. Rambøll Lighting believes that lighting that I designet af et belysningskoncept er det derfor vigtigt, supports, enhances and interacts with the function at de valgte belysningsniveauer, kontrastforhold, and architecture of a space creates a comfortable and farvegengivelser og farvetemperaturer harmonerer positive experience. i rummet, og at konceptet kan integreres i det lysstyringssystem, der er valgt ud fra brugerens behov. The lighting design must therefore ensure that the desired lighting levels, contrast conditions, colour Valget af den rette lysstyring vil endvidere give brugeren rendition and colour temperatures are harmonised and muligheden for nemt at kunne vælge forudbestemte can be integrated into the lighting control system. scenarier samt forøge energibesparelsen. In addition to offering energy cost savings, choosing the right lighting control system enables the user to select from a number of pre-defined lighting designs. Rambøll Lighting cooperate with clients to develop these settings and to ensure a final result, which offers the appropriate range of settings in relation to the client’s functional and aesthetic demands. Vi støtter os til FNs definition af bæredygtighed fra 1987 og søger med vores opgaveløsninger, at -

Fredede Bygninger

Fredede Bygninger September 2021 SLOTS- OG KULTURSTYRELSEN Fredninger i Assens Kommune Alléen 5. Løgismose. Hovedbygningen (nordøstre fløj beg. af 1500-tallet; nordvestre fløj 1575, ombygget 1631 og 1644; trappetårn og sydvestre fløj 1883). Fredet 1918.* Billeskovvej 9. Billeskov. Hovedbygningen (1796) med det i haven liggende voldsted (1577). Fredet 1932. Brahesborgvej 29. Toftlund. Det fritliggende stuehus (1852-55, ombygget sidst i 1800-tallet), den fritliggende bindingsværksbygning (1700-tallet), den brostensbelagte gårdsplads og kastaniealléen ved indkørslen. Fredet 1996.* Delvis ophævet 2016 Brydegaardsvej 10. Brydegård. Stuehuset, stenhuset (ca. 1800), portbygningen og de to udhusbygninger (ca. 1890) samt smedien (ca. 1850). F. 1992. Byvejen 11. Tjenergården. Det firelængede anlæg bestående af et fritliggende stuehus (1821), tre sammenbyggede stald- og ladebygninger og hesteomgangsbygningen på østlængen (1930) samt brolægningen på gårdspladsen. F. 1991.* Damgade 1. Damgade 1. De to bindingsværkshuse mod Ladegårdsgade (tidl. Ladegårdsgade 2 og 4). Fredet 1954.* Dreslettevej 5. Dreslettevej 5. Det firelængede gårdanlæg (1795, stuehuset forlænget 1847), tilbygningen på vestlængen (1910) og den brolagte gårdsplads. F. 1990. Ege Allé 5. Kobbelhuset. Det tidligere porthus. Fredet 1973.* Erholmvej 25. Erholm. Hovedbygningen og de to sammenbyggede fløje om gårdpladsen (1851-54 af J.D. Herholdt). Fredet 1964.* Fåborgvej 108. Fåborgvej 108. Det trelængede bygningsanlæg (1780-90) i bindingsværk og stråtag bestående af det tifags fritliggende stuehus og de to symmetrisk beliggende udlænger, begge i fem fag, den ene med udskud og den anden forbundet med stuehuset ved en bindingsværksmur forsynet med en revledør - tillige med den brostensbelagte gårdsplads indrammet af bebyggelsen. F. 1994. Helnæs Byvej 3. Bogården. Den firelængede gård (stuehuset 1787, udlængerne 1880'erne). -

Finn Juhl(30 January 1912 – 17 May 1989) Was a Danish Architect

Finn Juhl (30 January 1912 – 17 May 1989) was a Danish architect, interior and industrial designer and industrial designer, most known for his furniture design. He was a leading figures in the creation of "Danish design" in the 1940s and he was the designer who introduced Danish Modern to America. Wikipedia Finn Juhl Finn Juhl was born January 30th 1912 at Frederiksberg as son of cloth a subject of discussion. The furniture architects, who were known, all merchant Johannes Juhl and his German born wife, who unfortu- had either a carpenter’s education or were educated by Kaare Klint at nately died three days after the birth of little Finn. The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture. But not Finn Juhl, who was self taught and who broke the craftsman like He grew up together with his two years older brother Erik Juhl and traditions within the design of furniture. their authoritarian father in a home with Tudor and Elizabethan din- ning room, leaded windows and tall panels. Even though there was a lack of acknowledgement to begin with of Finn Juhl’s furniture design, he, ten years after his debut, got his fur- Originally Finn Juhl wanted to become an art historian but his father niture in a series production at the company Bovirke and later with persuaded him to join The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School France & Son, and others. From 1951 the company Baker Furniture of Architecture after his graduation in 1930. During the Summer of Inc. in Grand Rapids, Michigan produced his furniture in USA. -

Formanden Skriver 3 · Referat Af Prisfest 4 · Pristale 6 · Takketale 10 · Interview Med Gerda Leffers 15 · Sprogseminar 18 · Invitation Til 30-Års Fødselsdag 20

Nyt fra Modersmål-Selskabet 27. årgang nr. 3 September 2009 Indhold: Formanden skriver 3 · Referat af prisfest 4 · Pristale 6 · Takketale 10 · Interview med Gerda Leffers 15 · Sprogseminar 18 · Invitation til 30-års fødselsdag 20 Tal Modersmål-Selskabet fylder 30 år til november, skuffelsen over, at det udvalg, som Jørn Lund stod i og lidt inden fylder bestyrelsens længst siddende spidsen for, og som resulterede i rapporten „Sprog medlem Gerda Leffers 90 år. Det er ikke for meget til tiden“, ikke kunne nå frem til en entydig anbe- sagt, at Selskabet var gået mindre styrket ind til sit faling af en sproglov. Nu skal rapporten til høring jubilæum, hvis ikke Gerda Leffers havde lagt sin i Folketinget, og inden da skal mange partier bi- sjæl og arbejdskraft i Selskabets virke, i en periode lægge interne stridigheder i spørgsmålet. Men fra som formand og alle årene som hovedkraft i årbo- anden autoritativ side er der støtte til ønsket om gens tilblivelse. Om årene i Modersmål-Selskabet en egentlig sproglov, ikke mindst i tilknytning til og sit forhold til sproget fortæller Gerda Leffers Universitetsloven. På et seminar i september ud- i en samtale med Selskabets ny formand Jørgen trykte Dansk Sprognævns afgående formand Niels Christian Wind Nielsen i dette nummer, der også Davidsen-Nielsen stor utilfredshed med de vage på anden vis står i festens tegn. Årets modtager af hensigtserklæringer og markerede hermed den of- Modersmål-Prisen Jørn Lund blev hyldet i Radio- fensive deltagelse i debatten, der har kendetegnet ens gamle koncertsal, og selv om Jørn Lund blev nævnets arbejde i hans formandstid.